Are Green Berets Turning Pink? Integrating Women into Special Forces

We are seeking to fill two positions on our editorial team: An editor/researcher and a membership editor. Apply by Oct. 2, 2022.

Is advancing women’s interests worth destroying America’s most elite military units? One can hardly peruse media (social and otherwise) without hearing histrionic tales of plummeting standards and woeful urban legends of the crumbling of our sacred institutions. Gender-neutral physical fitness tests, time-honored events removed from the training calendar, and gender-integrated barracks — with all these changes, its easy to question if the standard is still the standard. Can America’s special operators withstand yet another social experiment? The reality is that there is no real evidence to support this narrative: Standards have not been altered to accommodate women. Our investigation suggests that assessment and selection for U.S. Army Special Forces is as hard as it has always been.

The lifting of the Combat Exclusion Policy in January 2013 opened the ranks of U.S. Army Special Forces, the vaunted Green Berets, to female soldiers. To date, only a handful of women have qualified for Special Forces Assessment and Selection, and even fewer have been successful. In fact, assessment and selection standards are so rigorous that it took years for the first woman to be selected. Regardless, now that women have successfully navigated assessment and selection, there is an opportunity to evaluate the possibility of bias in assessment and selection and apply corrective measures if need be. The assessment and selection model is a decades-old system originally designed to assess only male candidates, which was created in 1988 by Gen. James A. Guest of the John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School. Institutionally, the schoolhouse is dutybound to evaluate the efficacy of the model.

While the contemporary addition of female candidates has not changed the original charter of Special Forces Assessment and Selection, it has revealed potential vulnerabilities regarding the selection, training, and integration of women into Special Forces. This process employs a unique training environment that allows the training cadre to identify and assess hopeful Special Forces candidates across multiple domains simultaneously. Considering that the mission is to identify and select the most qualified soldiers for the Army’s most critical missions, it is imperative to determine if the selection and training model correctly and accurately reflects the differences presented by introducing female candidates. My purpose here is not to evaluate the merits of women in Special Forces. Rather, I seek to explore the systems and processes in the training pipeline and their utility. The cognitive, psychological, and physical assessments in assessment and selection remain gender neutral and free of bias.

While the assessment and selection course remains steeped in mystery and rumor, there is a definite method to the madness. The 21-day course held at Camp Mackall assesses each candidate’s physical, mental, and emotional preparedness for continued participation in the Special Forces training pipeline, and it remains relatively unchanged since its inception. Special Forces Assessment and Selection follows a 3-week model of evaluation wherein week one is “individual week,” week two is “land navigation week,” and week three is “team week.” Standards of performance are key to the selection model and the process collects over 300 separate performance data points on each candidate. The first week includes standardized physical and cognitive assessments, timed ruck-march and run events, and the notorious “Nasty Nick” obstacle course. Land navigation week is a straightforward series of solo land navigation exercises.

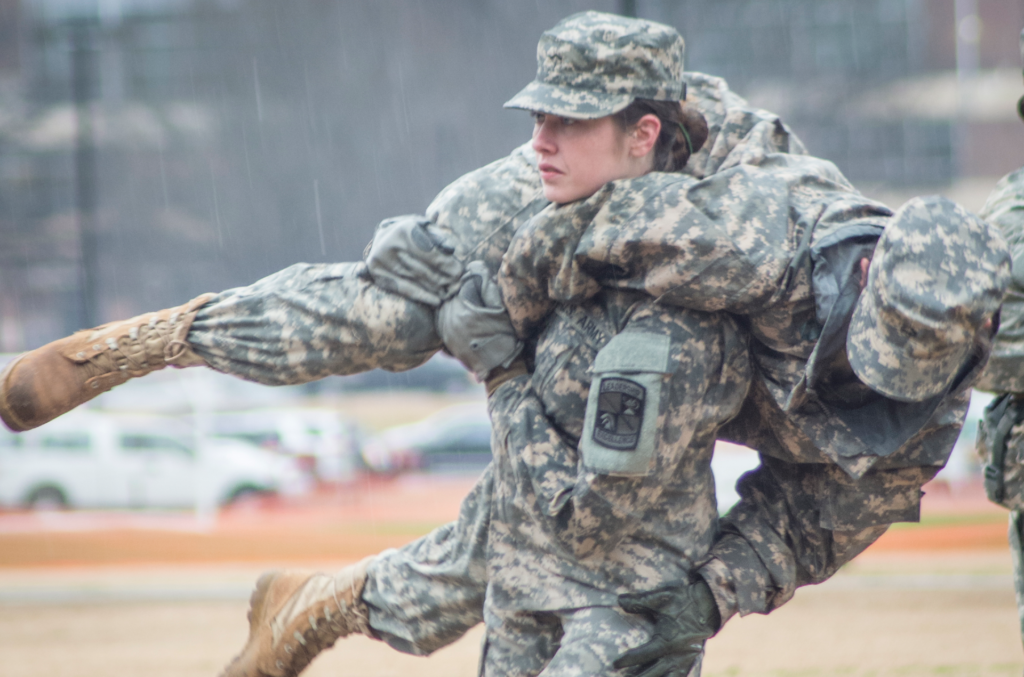

Those who have attended assessment and selection, even “non-selects,” generally agree that team week is the defining essence of the experience. Team week places candidates into assigned teams and confronts them with a series of challenges focused on intense field-based load carriage, problem-solving, and interpersonal dynamics that often seem herculean in execution. It is during team week that the cadre can evaluate each candidate’s ability to display attributes unique to the assessment and selection environment.

Despite course updates and refinements, the selection rate remains near the historical average of approximately 36 percent. As of the date of publication of this article, the selection rate for women is approximately 10 percent. Special Forces Assessment and Selection remains one of the most physically, emotionally, and psychologically challenging military training regimens in the world. Does this mean that contemporary selected candidates are just as qualified as the generations of Green Berets before them? The evidence is clear: Standards remain in place and are rigorously enforced. However, a lack of change in standards does not necessarily equate to a lack in biases.

Method to the Madness

To assess the validity of assessment and selection and determine if the methods are sound and whether systemic bias exists, our research team evaluated three key areas: the system, the training staff (the cadre), and the candidates. For two years, our team of researchers were granted nearly unrestricted access to Special Forces Assessment and Selection. Our conclusions are drawn from interviews of male and female candidates, the cadre and command teams, hundreds of hours of training observations by our research staff, and a quantitative analysis of candidate performance data.

The “Special Forces Assessment and Selection system” is a broad term our team used to encompass everything from recruiting, administration, and reporting for training to the actual course execution, out-counseling, and selection. Training observations include those from assessments of fitness, training, and combat readiness, as well as the obstacle course and team week. Our observations of each of these three categories of evidence indicate that the standards for assessment and selection have not been changed to accommodate women. Therefore, the selection process, while having evolved since its inception, displays no clear evidence of bias.

For the quantitative analysis, as mentioned above, each assessment and selection candidate has over 300 assessable data points. The specific data collected is part of a closely guarded and purposefully obfuscated process of assessment that includes physical, mental, and emotional components. As such, we can’t reveal the specifics of the process or the data. But we were able to evaluate each candidate’s individual performance data, in particular each female candidate’s performance, and compare it to all other candidates with specificity across assigned courses to ensure a consistent evaluation. The research team took the aggregate performance measure of female candidates and compared this to the aggregate performance of their male counterparts. In no case was a female candidate who performed below this aggregate selected. All selected women performed above this metric. Performance, and only performance, is the determining factor in selection.

While the cadre go to great lengths to remain unbiased, such precautionary measures cannot ensure that male and female candidates experience the Special Forces Assessment and Selection system exactly the same. For example, women have a different packing list than men. There are female-only items like brassieres, sanitary supplies, and a female urinary diversion device. During the packing list inventory event, or “shakedown,” female candidates must present these items to the cadre prior to beginning the course. While it takes the cadre about 30 seconds to verify these items during the event, it is a brief instance where female and male candidates are separated based on gender. Additionally, female candidates are required to demonstrate proof of non-pregnancy during in-processing. Early in the integration process, female candidates are required to take a urinary pregnancy test on site. This practice has since been modified to allow female candidates to bring in paperwork indicating a negative pregnancy test administered within 30 days of reporting for assessment and selection. This precautionary step is done to accommodate health and only takes a brief time to complete, yet it is another instance of a difference between men and women. However, none of the interviewed female candidates, the cadre, or members of the research team identified the shakedown or pregnancy test as biased.

During assessment and selection, women and men live in the same barracks, often sharing a bunk, with all of the normal barracks activity. Critics of integrating women into Special Forces often cite the close-quarters living conditions of forward-deployed Special Forces teams as potential areas of incongruity, yet no candidate cited barracks living as a point of contention. One might reasonably speculate that disrobing in close quarters would be problematic from a sense of privacy, societal conditioning, or simple humility, but no candidate, male or female, cited this as an issue. In addition to barracks activity, the research team’s evaluation of living conditions included a detailed assessment of latrine placement. Latrines for women are slightly further away from the barracks than the male latrines, which was a repeated point of discussion during the interview process. A 40-meter difference in location sounds like a small thing, but every step at assessment and selection counts, especially after a grueling day of physical exertion. Our research team determined that this area of difference did not equate to bias. However, what is perhaps the largest potential for bias or even inconsistency in assessment is that of the cadre.

The Keepers of the Standard

The cadre are key to the success of assessment and selection. The efficacy of the system is rooted in their high performance, professionalism, and ability to administer the training effectively. Special Forces culture is designed to minimize cadre “interference,” so that the only thing that separates selects and non-selects is the candidate’s own individual performance. In this environment, the strong candidates separate themselves from the weak with the cadre acting as a non-partisan, outside observer. Throughout years of observing and working closely with the assessment cadre, the research team observed the cadre make consistent, unbiased, and accurate decisions regarding course execution, candidate interactions, and event management. In my judgment, the cadre are unbiased in their assessment, or at least they are not operationalizing any existing bias. They are professional when discharging their duties, which is critical moving forward as more women qualify for selection. The cadre view their role in upholding fairness and impartiality at assessment and selection as almost sacred. They neither encourage nor discourage candidates. Our findings indicate that they do not allow rank, race, gender, or any immutable demographic trait to enter into the assessment process.

Not one candidate, male or female, cited any bias from the cadre — from the moment a candidate steps foot on the bus to Camp Mackall to the minute he or she leaves. In fact, most interviewed candidates communicated that they anticipated and expected bias from the cadre but could not cite a single incidence of such. The cadre have the potential to apply almost infinite pressures and bias, and they represent the single most impactful variable in the selection process. However, in reality, the cadre go to great lengths to remain unbiased in their selections. The cadre may deliver bad news when not selecting a candidate, but it is at the hands of the candidates’ own performance. While the research team found no bias within the system or the cadre, the same cannot be said for the candidates themselves.

Candidates Are Human Too

Candidates arrive at assessment and selection with established and engrained socialization skills that they exhibit throughout their assessment. During multiple observations under multiple conditions, the research team observed male candidates demonstrate preferential treatment to female candidates, which the team determined as the only source of bias. For example, male candidates were less likely to verbally call out weak physical performance from female candidates than from male candidates. Likewise, male candidates were more likely to physically assist weak physical performance from female candidates than they were to physically assist a male candidate’s weak physical performance. Our research team observed this phenomenon repeatedly and consistently, which leads us to consider candidates’ socialization as the biasing factor to assessment and selection. However, even with this phenomenon, the selection model still worked: No female candidate demonstrating sustained weak physical performance was selected. Nevertheless, our research team interviewed candidates and the cadre to evaluate this phenomenon further.

As noted previously, candidates were reluctant to call out weak performance from female candidates in the moment. When the research team interviewed candidates about this behavior, male candidates asserted that they were confident that the cadre were appropriately monitoring the events. In other words, male candidates were aware of the weak performance, but were reluctant to draw attention to the weak performance. However, this was only true for weak performance from female candidates. Male candidates did not show similar restraint with weak performance from other male candidates. The cadre simply noted the performance and allowed the candidate-teams to continue training. When discussing this phenomenon, the male candidates noted that they were just “acting naturally.” This reinforces the idea that this behavior is intrinsically encoded and is sub-conscious behavior as a component of the social environment.

The cadre insist on maintaining an atmosphere of non-interference so there is no established mechanism to intervene. What does this mean? The cadre can direct candidates to conduct a specific task or play a specific role. However, this is considered “interference” or bias. It happens only very rarely. The cadre will instead direct a team to do a task, but not individual candidates.

For example, one event involves the teams carrying a duffel bag full of sand, weighing about 700 pounds with a rig of lashed-up metal poles (this event is euphemistically called The Sandman) . This is combined with a jeep push for about eight miles. Since the load is heavy, pushing the jeep becomes a sort of ‘rest’ position. Candidates are in charge of the work/rest cycle and the rotation of positions. We learned that physically weaker female candidates stayed in the jeep-pushing position while stronger male candidates remained in the load-carrying positions. Male candidates would not enforce the rotation cycle between these positions, so the women did less work. The fact that weaker candidates tended to avoid the more difficult position is not noteworthy. The fact that male candidates would call out this behavior when it was other men doing it, while not calling it out when women did it is noteworthy.

The training cadre can and do easily observe this. I observed it myself and discussed it with many of the cadre. The cadre could (but never do) intervene and make a female candidate rotate to one of the more difficult positions. Doing so would violate the ‘neither-encourage-or-discourage’ culture of the assessment course. So, Assessment and Selection does demonstrate bias, but that bias is only from male candidates rather than the training cadre or the rules. Further, this bias favors women.

Is this a lowering of standards, as critics would claim? Not really. It’s not a performance standard. Rather, it’s an operational culture issue. If the Army were to alter the ‘neither-encourage-or-discourage’ ethos, then it would be introducing bias against women. Special Forces is beating itself on a technicality with its own rules. This might be the best argument for changing the selection methodology to allow for cadre to manipulate interactions so they can get a more holistic assessment. Taken to the extreme, the cadre could explicitly direct that a candidate remains in a position without rest for an entire event. In the case of the above-mentioned event, this might be catastrophic. This event humbles even the strongest of candidates. If the cadre were to maliciously manipulate work/rest cycles, they could easily force an entire team to quit. But I wouldn’t endorse any changes to the current system. Put plainly, it works. Having casually observed Special Forces Assessment and Selection for almost 3 decades, and closely studying it for nearly 15 years I am more confident than ever that it does what it was chartered to do. This is specifically true for female candidates. Our observations demonstrate that only performance matters.

Conclusion

The topic of integrating women into Special Forces is emotionally charged. Opponents cite liberal ideology, social experimentation, and a purposeful and targeted eroding of traditions as motivation for the change. It seems that the most often cited argument against integration is that “standards” will be lowered to accommodate women. The research team has reviewed training records from the last 12 years and physically observed operations across that timespan — beyond the two-year focused assessment of this study — and can confidently report that standards have not been altered to accommodate women. In fact, we are steadfast in our conclusion that assessment and selection is as hard as or perhaps even harder than it has ever been. The weights are the same, the individual events measure the same attributes, and Camp Mackall is still Camp Mackall. The barracks and latrines are nicer, but that’s about it.

Perhaps the only difference is that while standards are identical for all candidates, not all candidates are identical. Women have physiological differences compared to men. The gender-neutral standards for selection are quite high, which naturally favor bigger, stronger candidates, but that is not bias, it is just biology. To that end, the cadre endeavor to exercise systems and processes free from bias. Only top performance — physical, emotional, and interpersonal — is rewarded. The empirical human performance data supports this conclusion. However, candidate’s physical performance is not the only source of quantitative data at Special Forces Assessment and Selection. Considering the mixed opinions about integrating women into the Special Forces community, our research team predicted that peer evaluations would be consistent opportunities for bias. In this regard, we can report no bias exists. Female candidates that scored above average on peer evaluations were selected and female candidates that were evaluated to be below average were not selected — just as it should be. The evaluation model is working if candidates who perform and peer evaluate above average are selected and candidates who perform and peer evaluate below average do not get selected — regardless of rank, race, or gender.

Researching potential bias in assessment and selection is the first step in analyzing the integration of women into Special Forces. From a Special Warfare Center and School perspective, there is no pressure to force women through this program, but there is pressure to follow the process, and that pressure continues long after assessment and selection. Now that women have entered, and graduated from, the Special Forces Qualification Course, it is time to consider the next phase of integrating women. The course is the first time the Special Forces community at-large will get a glimpse at the reality of having mix-gendered teams. However, even as the first women graduate, they become a data point of low digits. There is still a lot of time before the community will have enough data to make any wholesale, informed changes. Military and civilian defense leaders should take caution before making drastic changes or sweeping conclusions with such little data to inform reforms. But it does not mean we cannot explore ideas, contemplate contingencies, and develop responses. In the meantime, American citizens, leaders, and military personnel should remain confident that Special Forces Assessment and Selection still works and is free of bias for all candidates.

David Walton, PhD is a retired U.S. Army Special Forces officer with 25 years of special operations experience. Walton spent a decade as a professor of national security affairs at the National Defense University. He has extensive operational experience in Latin America and the Middle East. He currently teaches with the Joint Special Operations Command. His work and research focus on operationalizing great strategy for better results. The views here are those of the author and do not represent those of U.S. Army Special Forces, the U.S. Army, the U.S. Department of Defense, or any part of the U.S. government.

Image: U.S. Army photo by Staff Sgt. Ken Scar.