U.S. Defense Strategy After the Pandemic

After a year of loss and lockdowns, America’s vaccination efforts are slowly allowing the country to reopen. At long last, things are very slowly starting to feel normal. Among other things, this moment provides analysts the opportunity to consider how the pandemic has affected domestic support for America’s defense strategy, and whether the country will be able to afford it over the long term. This will be a difficult conversation, as it will necessarily require questioning longstanding assumptions in America’s strategic community.

Former Deputy Secretary of Defense Robert Work kicked off the conversation in a recent article. Published before the Biden administration released its Fiscal Year 2022 presidential budget request, Work’s essay highlighted the difficult trade-offs facing Defense Department leadership if, as he anticipated correctly, defense spending remained flat over the next year.

While Work raised a number of salient points, I’m concerned that his analysis will ultimately prove too optimistic. After the devastation of the pandemic, Americans and their leaders in Washington are right to scrutinize defense spending when investments in public health would seem to have a more direct impact on their well-being. In my view, it’s entirely plausible that in the near- to medium-term, the Defense Department will have to grapple with deep spending cuts.

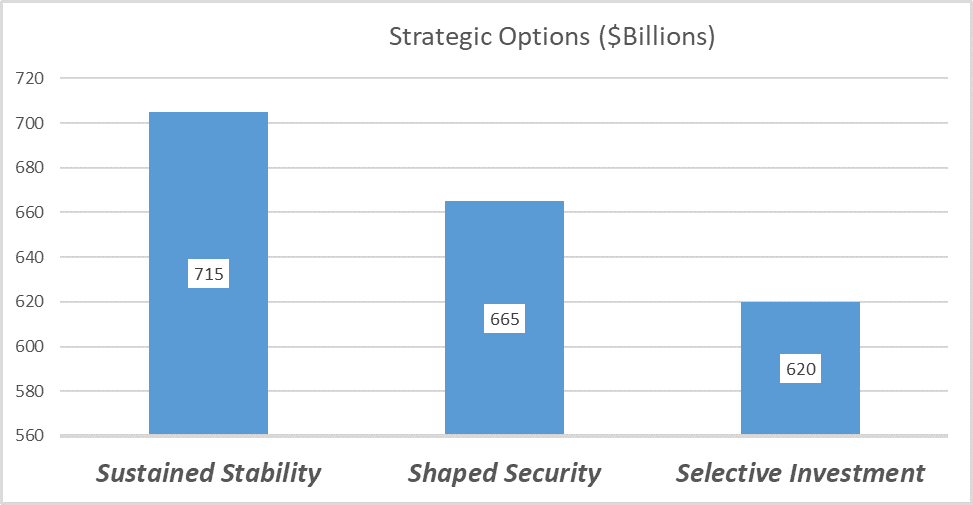

The Pentagon may wish to continue to implement the 2018 National Defense Strategy as if the pandemic and recession never happened — but it would only be wishing. Instead, the policy and strategic community should evaluate U.S. national security strategy under much more austere defense spending scenarios. The purpose of this article is to push past the now dated assumptions of 2018 and catalyze a debate updating my Foreign Policy Research Institute study about pressing strategic trade-offs and Pentagon resource options. This article offers three distinct Defense Department budget levels (a flat-lined $715 billion at new FY2022 request level, a 5 percent reduction to $665 billion, and a 10 percent cut, which would bring defense spending down to roughly $625 billion). The article outlines general defense strategies for these scenarios. Each strategy — sustained security, shaped security, and selective security — has different foreign policy implications, different force levels, and resourcing priorities to best match means with ends.

Strategy and Budget Scenarios

The U.S. defense budget could be significantly impacted by the national socioeconomic fallout from the pandemic. The Pentagon has spent the last few years implementing a National Defense Strategy focused on strategic competition with major powers. It’s fairly certain the Defense Department will not get the sustained and stable funding needed to fully implement the National Defense Strategy. A number of conservative defense analysts have recognized that defense spending will be cut over time. As noted by Work and others, the fundamental economic assumptions undergirding that strategy are not valid anymore, and more than a cosmetic rewrite is now required to align ends with limited means.

The following sub-sections explore three potential future defense spending levels (see Figure 1), with the associated impact of each on defense strategy. These are illustrative to raise key trade-offs, and are displayed in Figure 1. This analysis will address the Pentagon base FY2022 budget, which the Biden administration has submitted at $715 billion. The Office of Management and Budget outlined the president’s budget, which is less than the Trump administration’s submission ($722 billion), and represents a decrease in purchasing power when inflation and military pay increases are factored in. The administration’s request signals that the projected era of future flat budgets has arrived. Of course, Congress will ultimately decide the final budget.

Figure 1: Strategic Options and Funding Levels

Source: Chart generated by the author

Sustained Stability

The first option for U.S. defense strategy, “sustained stability” assumes that the president’s FY2022 budget request is a static level of funding for the next five or more years. This would negate the desired steady and predictable growth that past defense leaders stated was necessary to implement the National Defense Strategy. That strategy followed expectations for significant modernization funding and some growth in the size of the U.S. armed forces. Even with inflation covered, the department would have to continuously seek out efficiencies to pay for new programs or increased cost growth beyond inflation.

A flat spending level, with no additional funding for a larger Army and a bigger fleet, does not invalidate the National Defense Strategy’s major priorities. However, this scenario does undermine secondary objectives and missions including tasks in the Middle East or the Arctic, while also increasing risk in other theaters. However, some legacy programs (or a number of F-35 fighters) could be cut as seed corn for a new generation of what T.X. Hammes called the “small, smart, and many” instead of investing more into smaller numbers of very expensive and exquisite platforms like Ford-class carriers or manned bombers.

The Navy’s plans to increase the fleet to 355 ships and beyond would be postponed. As the Congressional Budget Office notes, the Navy’s shipbuilding plans were fiscally ambitious anyway. In this scenario, 300 ships would be the new goal for manned vessels.

While reducing the size of the ground force, this option would sustain a robust investment account for conventional forces, as well as enhanced space and cyber capabilities as detailed in the space threat assessment by the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

No alliance commitments would be reduced under this option. While some forward reductions could impact the Army, the United States would still meet commitments to allies in Asia and Europe.

Shaped Security

Under “shaped security,” the Pentagon’s budget would be reduced by about $40 billion per year to a $665 billion annual level. This budget reduction would focus on cutting U.S. military operations overseas, including operations in Afghanistan, Syria, and Africa, which in FY2020 were budgeted at $26 billion. Some reductions in the Army (three to five Army brigades) would have to be considered under this scenario.

The strategy under shaped security orients the U.S. military toward maintaining supremacy on the global commons, and a division of labor with its key allies on continental Eurasia and Africa. The force design would emphasize seapower and spacepower. The maritime services (i.e., Navy, Marines, and Coast Guard) would serve as the mechanism for America’s forward partnering maritime-based strategy with key allies. Mastery of the global commons is necessary to ensure the United States is capable of a global response to a crisis, and to preserve vital interests in international trade and freedom of navigation.

The Defense Department is currently not well postured in the Indo-Pacific theater. Indeed, a more flexible posture is needed. Naval and aerospace capabilities should be leveraged and adapted to achieve a more resilient vulnerable posture. There are alternative Air Force designs for increasing the contributions of aerospace capabilities against peer competitors in increasingly contested operating environments. Moving away from short-legged, manned fighters to long-range unmanned systems is an option, but will be a cultural shift despite resource and operational benefits. Additionally, the Space Force would a priority because, as former Defense official Jim Thomas has forewarned, “Whoever controls space will have an advantage in future terrestrial conflicts.”

There are strategic trade-offs to be made between current readiness and modernizing for the future. As Doug Berenson has argued in these pages, the Defense Department could get off the hamster wheel and look at reducing overhead and operating costs. Another option, which would capture potential savings, would be to rely more on the National Guard and reserve component to reduce costs. At least two of the service chiefs believe that modernization should be the priority. The Air Force chief of staff, Gen. Charles Brown, and the commandant of the Marine Corps, Gen. David Berger, have observed, “Our current readiness model strongly biases spending on legacy capabilities for yesterday’s missions, at the expense of building readiness in the arena of great-power competition and investing in modern capabilities for the missions of both today and tomorrow.”

Selective Investment

The darkest fiscal scenario would result in a snap back to sequestration levels that the Defense Department faced in the last decade following the recession of 2008 to 2009. That would bring the Pentagon budget down to roughly $620 billion, a level that could be termed “panquestration.” This strategy would pursue cuts in active-duty military personnel levels (as well as civilian overhead) to preserve modernization and investment capital.

Such a scenario, similar to the Center for Strategic and International Studies’ Innovation Superiority Strategy, would mandate a new national security strategy, as well as major revisions to the National Defense Strategy. It would require significant force reductions, reduced U.S. basing and exercises overseas, and changed modernization plans. Cuts in Navy battle fleet ships (from 300 to 260) would be required, as well as 30 tactical squadrons from the U.S. Air Force, including most non-stealthy and short-range fighters. Regrettably, this will constrain the Pentagon’s ability to build up the Navy fleet as desired, but it could still be enough to restore American maritime superiority in the Pacific. The Marines could be reduced to two full divisions and air wings. These reductions would, with little doubt, reduce America’s ability to sustain forward-based forces overseas. The United States would also have to reconceive and invest in a new theory of power projection operations.

This option takes most of the cuts in force size to protect future modernization needs. Further reductions in investment capital for research and procurement could hobble the U.S. military in the midst of an era with numerous emerging technologies (robotics, unmanned systems, AI, hypervelocity missiles, and quantum computing). Analysts find investments in these areas are already insufficient.

In the selective investment strategy, a focus on greater experimentation and investments in disruptive technologies in space, cyber, and hypervelocity missiles is privileged over existing force levels. Building off the approach initiated by Work, the principal imperative of this strategy would be a ruthless prioritization of capabilities for deterring major competitors, while carefully investing in a research and development portfolio for breakthrough 21st century innovations as outlined in the Third Offset Strategy. These ideas have been recently reinforced by former Senate Staff Director Chris Brose in his provocative book Kill Chain.

Assessment

These illustrative scenarios and strategies highlight the dynamics of risk, sustainable means, focused priorities, and trade-offs. As the national debt grows dramatically to provide relief from COVID-19, Congress and the Pentagon will likely have to consider such options about the future. A future of flat defense budget growth (sustained stability) does not require many trade-offs, and preserves America’s hard power so long as it’s modernized. Most importantly, it preserves the country’s ability to maintain commitments in a disorderly world. But this optimistic budget future is unlikely given the costs of the pandemic and internal security challenges in the United States. At the other extreme, an abrupt return to sequestration-level cuts may appeal to domestic needs, but would also be strategically irresponsible.

Shaped security offers a reasonable halfway point that allows the Pentagon to preserve deterrence and contribute to the collective security that has been key to U.S. defense strategy since World War II. It balances risk better than panquestration funding, even if the latter approach were allowed to be strategically shaped. But since U.S. security is enhanced by its extensive network of friends, partners, and allies via collective security, the shaped security strategy has merit. America will need its alliances and partnerships after the pandemic. More than at any time in the last 30 years, a revamped network of partners is critical to U.S. national security.

A key aspect of selective investment — a strategy to cope with massive defense spending cuts — is its sharp focus on technological competitiveness and capability development. The downside of the selective investment option is potentially large force structure reductions, and its dependence on achieving a number of breakthroughs in operational capabilities. The theory of success of this approach depends on these technological enhancements producing sustainable competitive advantages. There is a growing consensus that the country needs to invest in emerging critical technologies, particularly AI, that will shape economic prosperity and security in the future. As a comprehensive study by the House Armed Services Committee noted, “To remain competitive, the United States must prioritize the development of emerging technologies over fielding and maintaining legacy systems.”

The Biden administration recognizes the trade-offs involved in national security decision-making. Its interim strategic guidance wisely noted that the Defense Department should prioritize disruptive opportunities in its modernization plans. Husbanding scarce resources for research and development and critical, long-term modernization is an appropriate move for the administration. The Defense Department is not spending enough on the funding needed to appreciably impact defense innovation over time. While system development and demonstration budgets are heading in the right direction, this should be protected. They are the fiscal bridge to ensure that breakthrough capabilities transition from labs and prototypes to the combat forces.

Selective investment has foreign policy implications too, as a more technologically focused defense strategy could be perceived as a retrenchment in the near term and less effective in deterring opportunistic aggression. Allies such as South Korea or those in NATO may be unsure of the reliability of U.S. support, and would either invest more in their own defenses or adopt policies that accommodate North Korean or Russian interests in their respective regions. Unless selective investment were accompanied with nuanced diplomacy and technology cooperation, European states could pursue strategic autonomy more aggressively, and not coordinate with the United States on foreign policy and security affairs. At the same time, a reduced presence in Central Asia and the Middle East could leave a political vacuum for Russia or China to increase their influence (e.g., the recent Sino-Iranian agreement). Such shifts may set the ground for long-term success, but may also increase instability in the near term. As noted by now Deputy Secretary of Defense Kath Hicks, “getting to less” in the Defense Department’s outlays is not without risks.

A Broader Conception of National Security

These future strategic and budgetary options are not driven by a reflexive desire to gut the Pentagon, nor are they an excuse for slashing defense spending. Policymakers should avoid what former national security adviser H.R. McMaster calls “retrenchment syndrome.” At the same time, U.S. political leaders need to forge a new social contract and obtain public support for a national strategy that balances domestic needs and international obligations. Achieving a new domestic consensus on American foreign policy in the face of stark political polarization and income/health inequality will no doubt prove difficult.

U.S. policymakers and legislators need to expand their thinking and consider the country’s fiscal future. The federal debt recently passed the total annual economic production of the country. For many analysts, including this author, that level was usually held as some sort of a magic inflection point for how much debt the United States could carry. After that point, the United States would be seen as fiscally irresponsible, having overloaded the national credit card and burdened itself with high interest payments. That self-imposed mental inflection point has been passed, and the country’s economy is still humming along, and both the economy and the debt level are projected to grow unabated. So at least one widely held assumption has been disproved for now. Yet, another old assumption that should not be jettisoned is the value gained with the U.S. dollar as the global reserve currency. This “exorbitant privilege” is key to U.S. global influence and is worth retaining.

Defense cuts do not always follow recessions. But in the long run, the red ink used for the emergency needs to be put away and a degree of solvency regained. The politics of debt reduction are not going away. Hence, more cuts should be expected and the second scenario — shaped security, in which defense spending takes a 5 percent cut to $665 billion — is the most likely. The Peterson Foundation projects that by 2030 the U.S. government will pay nearly $2 billion a day for interest alone. Extensive government support is warranted in the current crisis, but it’s not sustainable for the long term.

Conclusion

Coping with the social and economic costs of the pandemic will draw on significant resources for public health and economic recovery. This will constrain Pentagon funding more than is currently envisioned. Some policy experts might prefer to isolate defense spending from this crisis, as if the pandemic’s fatalities, the recession, and rising deficits are irrelevant to national security. However, the pandemic has made clear that there is a price for undercutting health services, emergency stocks, critical infrastructure, and advanced research and development too. At the same time, there are trade-offs in cutting defense spending, measured in terms of risk to U.S. interests and those of its allies. The government will have to reconcile the tensions between these competing priorities for years to come.

A reshaped and rebalanced security strategy would not necessarily be a disaster for the United States, particularly if it creates a stronger and more resilient foundation for the country’s strength over the long term. Even at lowered funding scenarios, the United States would remain the best funded and most tested military on the planet. But regardless of the ultimate budget, if that funding is not carefully and prudently targeted toward tomorrow’s competitors, U.S. forces will be unprepared in the years ahead. Under any scenario, “business as usual” is not the operative paradigm going forward.

Frank Hoffman is a contributing editor at War on the Rocks, and works at the Institute for National Strategic Studies at the National Defense University. He earned his Ph.D. at King’s College, London. This article reflects his own views and not necessarily those of the Department of Defense.