The U.S. Defense Industry in a New Era

Does the United States have the defense industry that it needs? As China and other countries develop increasingly capable defense sectors, pressure rises on defense companies to remain in the forefront of global defense technology. While U.S. defense firms produced innovations in defense and aerospace technology that underpinned the Pax Americana through the Cold War and beyond, times are changing.

Just as threats are evolving — cyber, AI, hypersonics, hybrid warfare, anti-satellite weapons, and more — so too are the conditions that shape the U.S. defense industry. The industry faces a period of flat to declining Pentagon budgets, even as the Defense Department struggles to meet challenging strategic conditions caused primarily by the rise of China. The military is increasingly introducing commercial technologies and acquisition practices that have the potential to upend the traditional defense contractor business model. How will the industry respond? Will the United States get from the defense sector the innovation and value that it needs?

Turbulent Decades for Defense

By Sept. 10, 2001, a period of dramatic consolidation after the Cold War reshaped the U.S. defense industry. The industry had followed the lead of Defense Secretary William Perry. At a 1993 dinner held in the Pentagon for defense company executives — the so-called “Last Supper” — Perry warned executives that the post-Cold War peace dividend meant that the Defense Department would not be able to sustain enough demand to keep all the major players in business. So began a process of consolidation that consigned some long-established nameplates to history: Hughes Aircraft, McDonnell Douglas, E-Systems, and dozens of others were absorbed into the growing portfolios of Lockheed Martin, Boeing, Northrop Grumman, Raytheon, General Dynamics, and a handful of others.

What emerged was a small group of top-tier defense players with portfolios spanning a wide range of military hardware markets. A few, like Boeing (and later General Dynamics, via its 1999 acquisition of Gulfstream), were able to balance the post-Cold War defense downturn with major commercial aviation businesses. Others, like Lockheed Martin, experimented in the energy and telecommunications sectors, without sustained success. For example, the company shuttered its Lockheed Martin Global Telecommunications subsidiary in 2001 after three years in business.

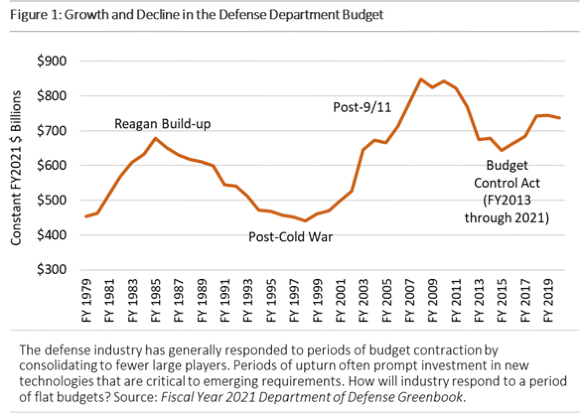

The attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, sparked a transformation of this landscape. Where the George W. Bush administration entered office aiming to “skip a generation” of technology toward a “transformation” of the U.S. defense establishment, the exigencies of the “Global War on Terror” imposed new realities. The Defense Department budget increased nearly 70 percent in real terms between Fiscal Years 2001 and 2010 to sustain and equip intensive counter-insurgency campaigns in Afghanistan and Iraq.

The defense industry pursued parallel paths, one defined by near-term operational demands and the other by longer-term threats. Responding to the former, firms ramped up production of urgently needed equipment and expanded services capacity to support extended land campaigns. Companies scrambled to repurpose existing technology to counter improvised explosive devices; field mine-resistant, ambush-protected vehicles; provide persistent overhead surveillance; and sift through mountains of intelligence data. Recognizing the growing role of contracted services to government requirements both in war zones and at home, companies expanded in logistics, engineering support, information technology, training, and other sectors.

A few companies made significant mergers and acquisitions moves directly relevant to the Global War on Terror. Lockheed Martin bought Pacific Architects and Engineers Incorporated (commonly known as PAE) in 2006, reflecting the rising importance of contingency logistics and humanitarian operations support. In 2011, General Dynamics augmented its combat vehicle business by buying mine-resistant, ambush-protected vehicle maker Force Protection.

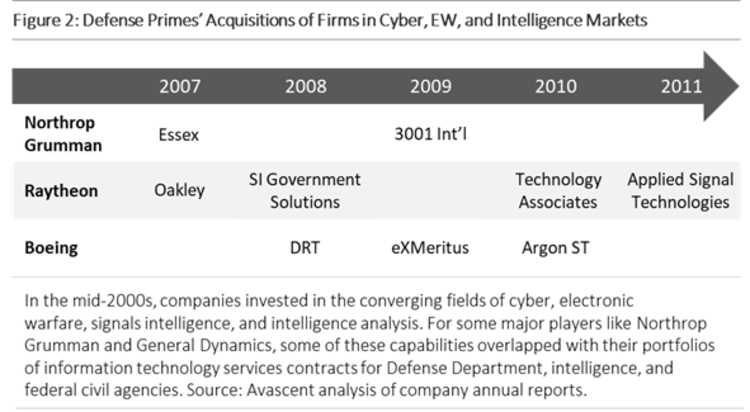

At the same time, defense players continued their focus on next-generation capabilities for conventional threats, particularly those employing anti-access/area denial strategies. In addition to areas like missile defense and unmanned aircraft, companies invested in the converging fields of cyber, electronic warfare, signals intelligence, and intel analysis. Again, merger and acquisition deals marked these emerging trends.

Transcending specific technology areas, defense companies shared an underlying strategy of trying to capture a larger share of the growing budget. Firms capitalized on commonalities in sales channels and management disciplines that are inherent in government contracting. Defense companies realized that their expertise in selling to the government was itself a core competency that could be adapted to a wider array of technical fields and customer groups, including many outside the Defense Department.

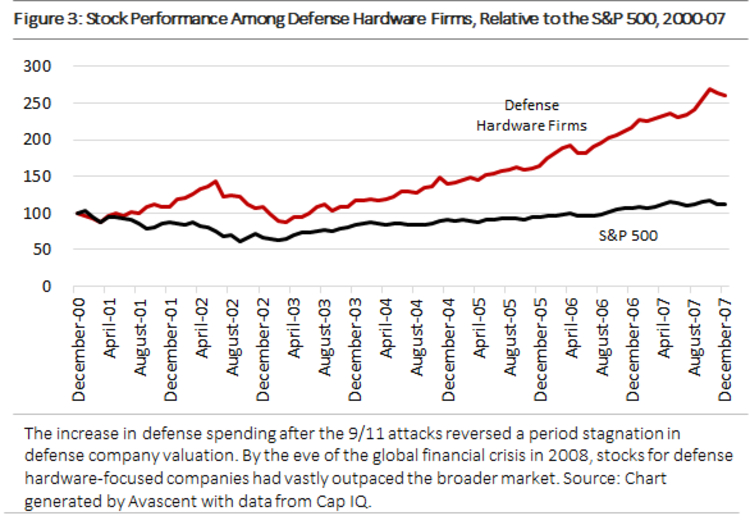

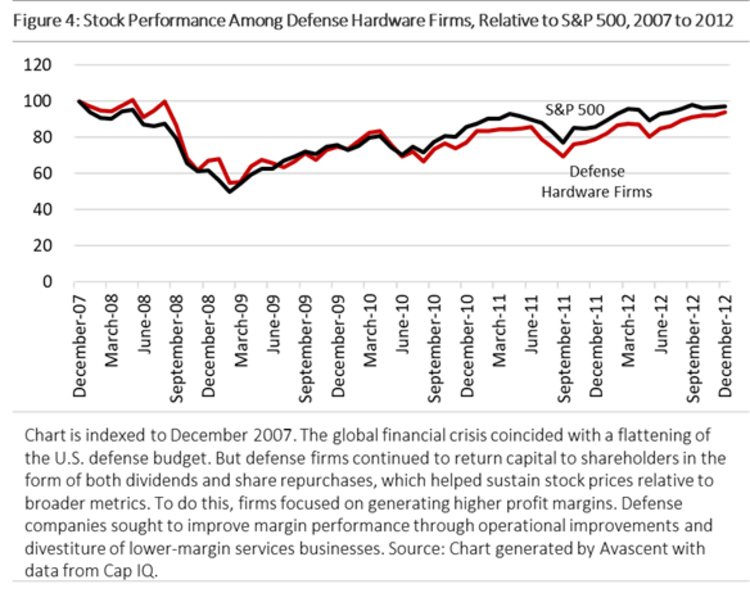

For investors, rapid growth in Defense Department outlays made defense stocks highly attractive, particularly after the collapse of the dot-com bubble and the recession of the early 2000s. From 2001 to 2007, defense stocks provided annualized returns of 14 percent versus a broader market that was up only 1 percent over the same period.

Inflection and Reaction

But as defense budgets neared their peak in FY 2008 to FY2010, the defense sector started to fall out of favor with investors. After consistently trading at a premium since 2003 relative to the S&P 500, defense stocks began to trade at a discount compared with shares in other industries. Rising concern over the federal budget deficit led to passage of the Budget Control Act in August 2011, undermining growth prospects for defense and, seemingly, the continued attractiveness of the sector to investors.

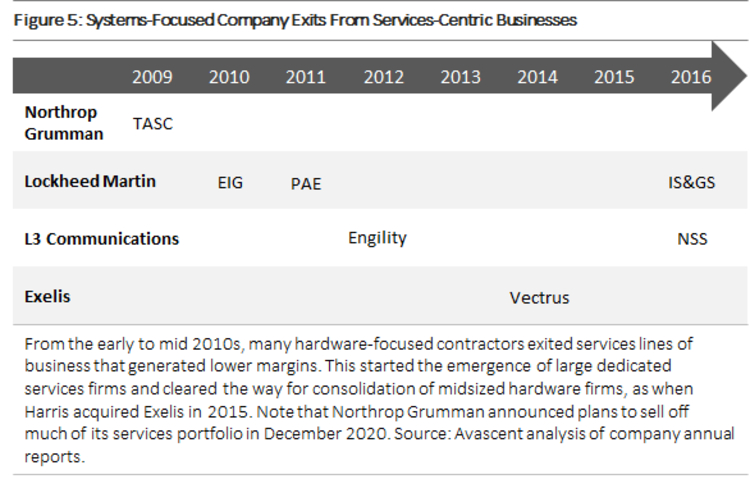

Leaders in the defense industry pivoted. If the first decade of the 21st century was dominated by the vice president for operations ramping up production or reengineering solutions for urgent needs, the second decade would belong to the chief financial officer. With topline growth proving elusive, firms sought to expand margins, making operational improvements and divesting less profitable businesses. Many hardware-focused contractors exited sectors that generated lower margins. As a result, between 2009 and 2014, a period when defense spending declined, industry margins improved by nearly 200 basis points to 12 percent.

The wave of divestitures led to a separation between a sector focused on military systems (and related commercial areas, like aviation) and one geared mainly to government services. This separation yielded two groups of competitors that offered investors very different financial parameters. Systems-centric firms aimed for higher profit margins, at least by the standards of stable, predictable government contracting (in the 10 to 12 percent range). At the same time, services-centric firms turned in lower margins (usually under 10 percent) but require much lower capital investment to achieve those results.

Defense systems firms also began returning a lot of cash to investors, both by increasing the dividend paid to shareholders and by buying back their own stock to increase the value of outstanding shares. The industry’s aggregate free cash flow allocated to these paths rose from less than 50 percent in the years following 9/11 to around 100 percent in the period 2011 to 2016. This return of capital to investors became a primary lever to generate shareholder value, given the expectation that new program starts would become more scarce under a declining Defense Department budget. Without a clear path to payoff from technology investment, firms calculated that returning cash to shareholders made sense.

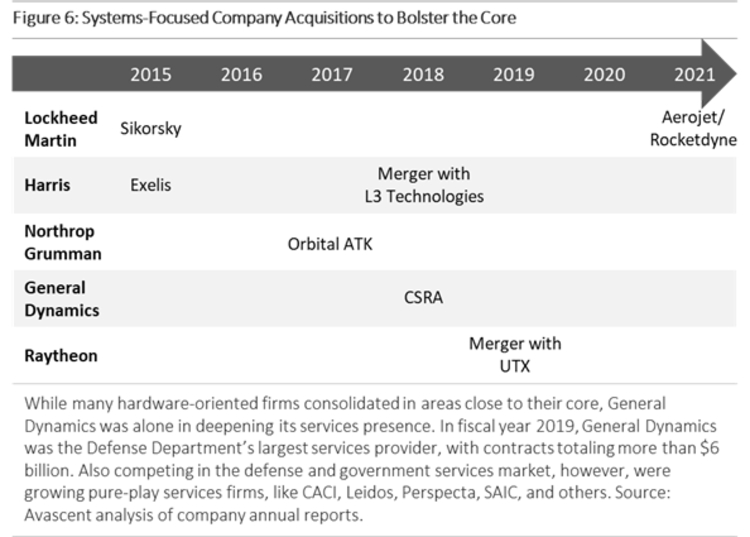

The winding down of operations in Iraq and Afghanistan refocused the industry’s attention on rapidly evolving conventional threats. Defense Department investment rose by nearly 50 percent from FY2015 to FY2020, signaling increasing demand for core defense systems and a reorientation toward challenges from China and Russia. This accelerated in the first years of the Donald Trump administration, with a big increase in the Defense Department budget and a National Defense Strategy that focused squarely on China. The administration also cut corporate tax rates, which combined to boost contractors’ bottom lines. In response, defense executives initiated a new round of mergers and acquisitions to invest in core technologies, whether in aviation, space, defense electronics, missiles, or information technology.

A More Complicated Future

If the past 30 years were marked by turmoil, the coming decade offers even less promise of stability or predictability. While political leadership in Washington may have changed, the strategic challenge posed by rising peer competitors has not abated. The Defense Department looks likely to pursue the same range of requirements with fewer resources. The Trump administration’s 2021 to 2025 spending plan envisioned no growth in the Defense Department budget in real terms. President-elect Joe Biden has yet to communicate his defense plans, but slow growth is probably the best that defense firms can expect. Under these conditions, the Defense Department will have to double down on changes in acquisition approaches that call into question some elements of the traditional defense business model.

Both political parties responded to the COVID-19 crisis by passing a series of economic stimulus measures, the most recent in the closing days of 2020. These largely ignored the effects on the federal budget deficit. Now, however, proposals for additional crisis response spending are stirring quiescent budget hawks to opposition. The Biden administration is unlikely to pursue deep cuts to defense, but neither will it provide the 3 to 5 percent real growth that Defense Department leaders under Trump have said is needed to fund the 2018 National Defense Strategy (a level that not even the Trump administration provided).

A more constrained budget will force the services to make difficult trade-offs among the size of U.S. forces, their readiness, and modernization. Beneath a flat or declining topline budget, costs related to personnel, operations, and sustainment tend to grow over time, putting progressively more pressure on modernization accounts. Within that investment budget, the department will struggle to balance legacy systems, current production programs, and next-generation research and development. Without strong congressional and service support, freeing up resources to sustain force modernization could prove extraordinarily difficult.

For the defense industry, program terminations could threaten backlogs, long-term business plans, and cost structure. Even less-extreme outcomes, such as lower annual production rates or slower progress in research and development programs, would have serious revenue implications. Existing business cases, even for franchise programs, could change profoundly.

Dynamism and Change in Acquisition Methods

Concomitantly, the defense industry will face further acquisition process changes that have emerged over the past decade. These reforms, begun during the Obama years under Better Buying Power initiative and accelerated during the Trump era, aimed to reduce costs, accelerate cycle time from requirement to solution, and gain more competition throughout a system’s lifecycle. At the same time, the Defense Department wants to harness the dynamism of the commercial digital economy.

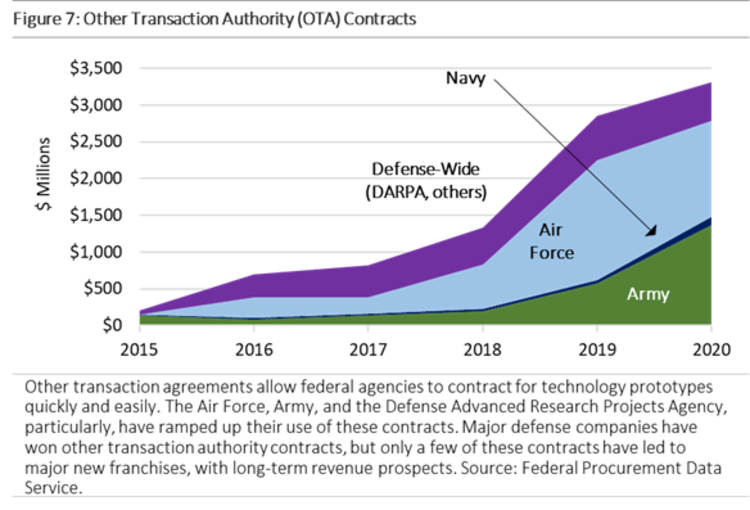

The Defense Department will increasingly use “Other Transactional Authorities” and other means to engage in prototyping and to leverage commercial technology investments. Other Transactional Authorities contracts could exceed $15 billion in FY2020 and represent a growing share of all investment dollars. The Defense Department’s experimentation with digital design and small batch purchases will become more common. This could yield more frequent, shorter-cycle development rounds, many of which will proceed no further and with only a few moving to production. Program concepts like the Air Force’s Digital Century Series and Next-Generation Air Dominance may involve shorter production runs than traditional franchises.

The services will make the use of Agile/DevSecOps and Modular Open Systems Approach paradigms the rule, rather than the exception, for software innovation. These methods are critical both for continual capability upgrades in a software-centric world and to reshape operating concepts for a more connected future. Combined Joint All-Domain Command and Control is central to this vision. Already, the Defense Department has engaged dozens of potential providers under the CJADC2 initiative using various contracting mechanisms to evaluate alternative approaches and technologies.

These practices may emphasize customers buying engineering/prototyping services on a cost-plus basis (i.e., a fixed profit margin on top of reimbursed project costs) without a clear link to long-term program positions. These developments will threaten profit margins, both by undermining the traditional model of recovering profits in full-rate production and by increasing the cost of competition through independent research and development and bid and proposal activities.

These pressures will feel even more constricting to longtime defense suppliers as the Defense Department increasingly tries to entice commercial firms to serve its needs. The Defense Department and the intelligence community have long sought to shift enterprise-oriented requirements toward commercial business models and providers, leading tech giants like Microsoft and Amazon to secure major contracts with defense and intel agencies.

But even in mission-oriented areas, the Defense Department has been increasingly open to non-traditional suppliers. The department hopes that more streamlined development processes will tempt commercial firms to compete for military programs. There are signs that it is making real progress: SpaceX now shares the National Security Space Launch role with United Launch Alliance, Microsoft is supplying the Army’s Integrated Visual Augmentation System, Palantir elbowed its way into the contract for the Army’s Distributed Common Ground System, and General Motors won the US Army’s Infantry Squad Vehicle contract in 2020.

All of this is happening as the global defense market is rapidly evolving. More and more countries are investing to develop world-class domestic defense industries of their own. Even as they import high-end defense systems, many foreign governments are applying increasingly stringent technology and work sharing requirements, which make exports a much more challenging proposition for U.S. and other Western defense firms. These trends are giving rise to new global competitors from South Korea, Turkey, Israel, and other countries, while Chinese and Russian firms look to make inroads among buyers who once mainly favored U.S. and Western sources.

These forces will not be so abrupt as to pose an immediate threat to the traditional defense industry. And major platform franchises will remain essential to the U.S. military’s force structure. Indeed, there is unlikely to be another “Last Supper” that offers a clear signal to downsize production capacity. Instead, today’s leaders will face an incrementally challenging environment in which old playbooks become less effective, making growth and profits harder to come by. Investor perceptions of defense as a safe haven with long technology cycles will erode over time without actions by defense executives.

Getting Strategy Out of the Back Seat

U.S. defense executives’ successful navigation of the past 20 years has been impressive. They effectively served Defense Department demands while simultaneously keeping shareholders satisfied. Much of their success is attributable to adept financial management, strong operational execution, and timely acquisitions. What is striking, however, is how uniform the industry’s response has been. While there are variations on the theme, the approaches were broadly the same: Invest alongside the customer in growing areas and judiciously allocate capital.

Unconventional strategies were largely unnecessary as budgets increased in the first decade of the 21st century. The discipline of the chief financial officer sufficed during leaner years to produce attractive returns. At times, strategists seemed to take a back seat to other corporate functions, and “strategic” planning became a matter of updating the operating plan and keeping an eye on competitors. Where strategy organizations did intercede, the results were often mixed. Investors were largely unimpressed with forays into telecommunications, soft power, or commercial cyber, preferring return of capital to speculative efforts that seek to transform pure-play defense companies into something new.

The essence of strategy is the prioritization of resources and actions to attain goals amid prevailing conditions. Given the state of flux in technology, customer, and competitive conditions, corporate strategists should carefully gauge how they are positioned to meet the moment. This will involve not just reviewing where they stand from a portfolio perspective, but also taking steps to revise their enterprises in line with new realities. Finally, strategists may need to reimagine the fundamentals of how they generate value.

Review

An effective strategy should be grounded in a cold-eyed assessment of a company’s market position. A rigorous analysis of the strengths and weaknesses of its portfolio and opportunity pipeline is essential to comprehend a company’s point of departure into a period of uncertainty.

This assessment should clarify the alignment between the company’s stated strategy and the emerging defense technology, acquisition process, and competitive dynamics. At this moment in time, when the Pentagon’s budget and its stated requirements are fundamentally misaligned, companies need to assess the vulnerability of their (and their competitors’) portfolios to a mix of weakening customer support, outsize budget requirements, technical risks, or the viability of alternative solutions.

Too often this activity focuses on downside risks, which is natural. But an effective portfolio review can open executives’ eyes to new opportunities. Identifying emerging growth areas or opportunities arising from vulnerabilities in competitors’ portfolios can help firms think about moving into new areas.

Revise

Many U.S. defense companies face conditions that make it hard to seize emerging opportunities. Firms may persist in business processes geared to a more “traditional” era, and their technology portfolios may not account for new directions. Further, a culture centered on traditional approaches to research and development, program capture, and keep-sold activities will fixate leaders on the past. Even directives to adopt Agile and similar practices can mask tendencies that remain highly traditional.

For example, a traditional investment practice is to allocate a share of business unit profits for independent research and development investment. This aims to ensure that successful programs benefit from reinvestment, sustaining them through multiple upgrade cycles and insulating them from competitive challenge. However, in a period of disruption to major programs, executives need to consider prioritizing potential new opportunity over elusive stability.

Similarly, corporate leaders may need to shift program capture priorities from the largest “expected value” targets — which may not all feature favorable competitive dynamics — to focus on smaller near-term wins that might unlock emerging positions and disrupt competitors. Amid this revised capture strategy, executives should link investment and capture more fundamentally and consider the gain in probability-of-win and probability-of-go that each marginal investment dollar can bring.

Reimagine

Finally, corporate strategists may need to consider more fundamental questions around business models and how they create value. Moves to rethink how a defense enterprise is structured would need to respond to shifts in customer behavior and market conditions that may upend parts of the traditional defense business model.

Potential Shifts in the Defense Industrial Landscape

Shifts in the Defense Department and the defense market overall could take many forms but a few possibilities are worth considering, based on emerging trends.

More Defense-Commercial Players

The merger of Raytheon and United Technologies represented a strong vote of confidence in the compatibility between defense and commercial aviation technologies and market sectors. The merged company is certainly not the first to plow this ground. Boeing, Airbus, Thales, and General Dynamics all span the military-commercial aviation divide.

But several developments suggest new urgency in this model. First, amid the COVID-19 pandemic, commercial air travel — and valuations for aviation companies — have cratered. This means that bargains are out there to be had in the commercial aviation supply chain. Second, given the Defense Department’s appetite for commercial innovation, drawing from outside the defense supply chain for technology and process improvement may be worth exploring.

Rising Vertical Integration

Several trends could lead prime contractors to acquire more of their suppliers. These include rising Defense Department concern for supply chain security and greater scrutiny of cyber security practices across all levels of the industry. The idea that the Defense Department’s appetite for innovation will emphasize mission systems far more than platform design or manufacturing may also lead companies down this path. Lockheed Martin’s announcement in December 2020 that it would buy Aerojet/Rocketdyne indicated what could be the first of many such transactions.

Expansion of Private Capital in the Defense Space

Private capital (as opposed to publicly traded companies) has made inroads in many sectors over the past several decades. But in the defense market, privately held companies have made their mark far more than most observers might have guessed 20 years ago. In areas like space launch, unmanned systems, and intel data analysis, private companies have changed the landscape fundamentally. SpaceX, General Atomics, and Sierra Nevada are all examples of privately held companies competing in complex defense technology sectors. The range of private equity-owned firms competing in the defense and intelligence space is even wider.

This is likely to continue. While government markets can be intensely regulated, the defense market features dynamics that make it unusually hospitable to private firms. With widespread use of cost-plus contracting and government sponsored research and development, there are limits to the risk that enterprises need to take on and the capital they need to raise. When it comes to taking risk, however, privately held companies can work on time horizons and metrics that publicly traded companies cannot.

There has been increasing talk in 2020 of publicly traded defense companies being taken over by private investors. In January 2020, Cobham was acquired by Advent International Corp. In the fall of 2020, activist investors were positioning to pursue Cubic with similar intentions. This may be the start of a trend that gradually makes the defense industry more risk-tolerant and thus more innovative than it has been. That would be a development that Defense Department leaders could applaud.

Conclusion

The U.S. defense industry has remade itself several times over in the decades that followed the fall of the Berlin Wall. Shifting to align themselves with the needs of both their customers and their investors, defense firms have tailored their portfolios, revised their technology investment focus, and experimented with new business models, all with profound implications for the U.S. military and its partners and allies. Now defense companies are seeing new competitive challenges, changing customer behavior, and the prospect of flat defense budgets. This will require corporate strategists again to review their outlook, revise their organizations, and reimagine their businesses.

The stakes for U.S. national security could not be higher. Having a vibrant and financially successful defense industry is critical to America’s ability to innovate defense solutions at a time when China and other countries are rapidly developing their own robust defense industrial sectors.

Doug Berenson is a managing director at Avascent, a global consulting firm serving clients in government-driven markets like defense, aerospace, and cyber. Doug has been with the firm for 20 years, helping government and corporate clients forecast trends in demand, weigh investment options, and make effective policy decisions.

Chris Higgins has over 18 years of industry, equity research, and consulting experience in the aerospace and defense sector. Chris is a Principal at Avascent helping clients at the intersection of finance and strategy. He spent 10 years at Airbus, where he served in a variety of finance, mergers and acquisitions, and strategy roles. Chris also covered aerospace and defense stocks as a sell side equity analyst.

Jim Tinsley is a managing director at Avascent and has served clients in the defense industry for nearly 20 years. He supports a range of systems-focused government contractors and agencies across land; air; naval; missile; and command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance.