2020 War on the Rocks Holiday Reading List

This year perhaps more than most a good book is a welcome companion for the wintry season. To that end, here is our annual roundup of favorite books from the War on the Rocks family. We hope you’ll find something for everyone on this list, whether your taste runs to nonfiction or sci-fi.

Happy holidays from all of us to all of you.

David Barno

The Wizard War by R.V. Jones. A classic World War II account of the British battle for scientific supremacy over the Third Reich. R.V. Jones was a 28-year old scientist at the beginning of the war who quickly rocketed to the top of British scientific intelligence, and whose brilliant insights on German rocketry, radar and direction-finding capabilities helped saved countless allied lives. Written with droll humor, this book provides fascinating insights not only into the critical wartime relationships and fast-moving science, but into life as a civilian in war-torn Britain. Of key importance to us today, this account describes a remarkable wartime marriage of civilian scientists and senior military leaders that the United States would be hard-pressed to duplicate in a future conflict.

Apollo’s Arrow by Nicholas A. Christakis. One of the first, and so far best books out on the coronavirus pandemic and its implications. The author, a physician, sociologist and Yale professor, jumps out ahead of the pack to provide vital insights on the sudden emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, and how its cascading effects will shape much of the rest of this century. Christakis breaks down this staggering event and its projected aftermath into recognizable phases, but the timelines he chooses may rattle you: immediate (through 2022), intermediate (perhaps through 2024), and post-pandemic (2024 and beyond). This is a timely and important book that can help us grapple with what is happening now, and begin to think about how this cataclysmic global disruption will forever alter significant elements of our world.

Mike Benitez

Good Strategy/Bad Strategy: The Difference and Why It Matters by Richard Rumelt. This should be required reading for anyone involved in developing, discussing, or executing strategy. The reason is simple: This easy-to-read book is the tool to dissect the elements of strategies and permits the reader to easily identify the difference between a good strategy and a bad strategy. Even better, it helps the reader tell when oft-touted “strategies” aren’t actually strategies at all.

Nora Bensahel

Both of my pandemic-inspired book clubs picked The Vanishing Half, by Brit Bennett, and for good reason. It’s an easily readable but nonetheless thought-provoking story about the meaning of identity, and how family secrets extend across generations. The story starts in the 1960s, with two twins who grow up in a town of African-Americans with very light skin. Their lives diverge as teenagers, when one decides to pass as white and cuts herself off from the rest of her family. Their stories continue through their grown daughters, who face their own challenges with identity and the family secret that unknowingly affects them both. Bennett’s book is riveting and beautifully written, and will stay with you long after you turn the last page.

I’ve just ordered The Evening and the Morning by Ken Follett, which is a prequel to one of my favorite books of all time, The Pillars of the Earth. I’m usually not a huge fan of historical fiction, but I could not put down Follett’s spellbinding tale of lively characters in an English town during the Middle Ages. Themes of love, loyalty, and betrayal unfold alongside those of religion and hypocrisy as the townsfolk continue the decades-long effort to build a cathedral. As we settle in for a long, socially-distant winter, you won’t find better company than the people of Knightsbridge – and you can continue to follow them in two sequels and now the prequel too!

Claude Berube

Rome and Parthia: Empires at War: Ventidius, Antony and the Second Romano-Parthian War, 40-20 BC by Gareth C. Sampson. Any reading of Julius Caesar’s The Gallic Wars should be accompanied by Gareth Sampson’s new work on the wars to the east of Rome. In the midst of civil war, Rome and Parthia engaged in their own great-power competition where smaller kingdoms and empires (such as the Armenian Empire) rose, fell, and were consumed by larger forces.

Dead Wake: The Last Crossing of the Lusitania by Erik Larson. Larson’s work on the Lusitania’s fateful voyage is valuable for telling the stories of people aboard in a popular history, but more importantly for studying the decision-making made by the British Admiralty and the operations of the U-boat that sank this ocean liner.

The Harps that Once…: Sumerian Poetry in Translation by Thorkild Jacobsen. If I may offer a third recommendation that is not focused on military operations or foreign policy, it is Thorkild Jacobsen’s The Harps that Once…. Don’t read it just for the poetry, but for the realization that these texts have survived 5,000 years of human conflict. While we end a divisive political year in the United States and face ongoing international challenges, we need to remember our common humanity, our common heritage, our common culture that we all can see in the words and lines of this work.

Brad Carson

Twilight of the Elites: Prosperity, The Periphery, and the Future of France by Christophe Guilluy. This book, a sensation in France, is an indictment of globalization and a defense of what Guilluy, a geographer, calls “lower France” — the working class of its small towns and rural areas. The analysis is equally applicable to our own nation, alas.

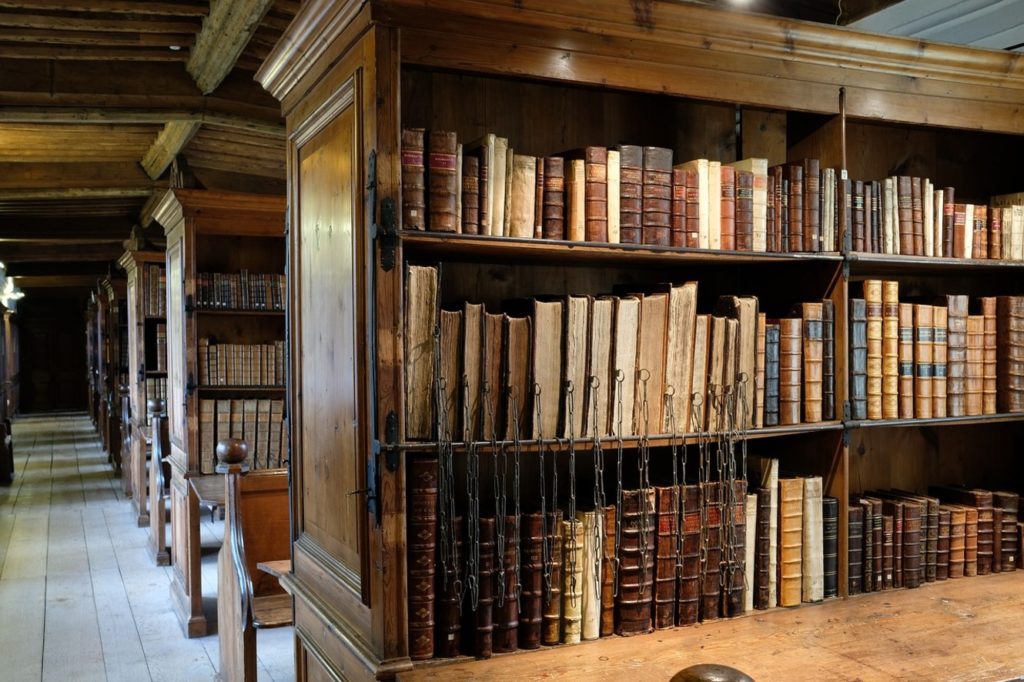

Breaking Bread with the Dead: A Reader’s Guide to a More Tranquil Mind by Alan Jacobs. Stressed out by the turmoil of recent months or even recent years? Jacobs recommends “breaking bread with the dead,” a phrase lifted from Auden and one which urges us to listen more closely to the heroic voices of the past, in this case writers like Virgil, Homer, Ibsen, Wharton, Calvino, and Levi-Strauss. Short but epigrammatic, the book packs a lot into a few pages. But it, too, like Guilluy’s book, suggests something has gone, well, very wrong in contemporary life.

Ryan Evans

An Open World: How America Can Win the Contest for Twenty-First-Century Order by Rebecca Lissner and Mira Rapp-Hooper. It is a blessing to have dear friends who are brilliant thinkers. Rebecca and Mira lay out a solid vision for American grand strategy in a post-Trump world. I sincerely hope this book is on the bedside tables of President-elect Joe Biden’s recently announced cabinet choices.

Adaptation under Fire: How Militaries Change in Wartime by Dave Barno and Nora Bensahel. This book represents many years of thinking and research by two of our most important thinkers about war. While I hope senior defense officials, present and future, are reading this as well as folks with stars on their shoulders, it’s probably more important in the long-run that military officers down to lieutenants and ensigns add this to their growing libraries.

Richard Fontaine

America in the World: A History of U.S. Diplomacy and Foreign Policy by Robert B. Zoellick. Diplomatic history is, as Bob Zoellick observes, a now-neglected art form. But there is much to learn from it, and this book teaches masterfully. Anything but a dry accounting of diplomatic exchanges, Zoellick examines a variety of events and individuals from the nation’s history, and mines their experiences for lessons important today. Total must-read.

The Three-Body Problem by Cixin Liu. I’m late to this mind-bending, easy-to-read trilogy, but it’s worth checking out. It helps if you’re interested in China’s Cultural Revolution, basic issues in orbital mechanics, and aliens from outer space. Who’s not?

Ulrike Esther Franke

Uncanny Valley: A Memoir by Anna Wiener. A twenty-something college graduate moves from New York to Silicon Valley to see what the fuss is all about. Anna Wiener adopts a brilliant, detached-yet-totally-drawn-into-the-tech-ideology voice to describe her experiences as a non-tech woman in a tech world at its apex — or the beginning of its end. I found the book tremendously insightful on Silicon Valley culture, and on how surveillance capitalism came about with many in the system either not realizing it, or not caring.

Infinite Detail: A Novel by Tim Maughan. Dystopian novels give me nightmares. And yet, it is important to engage with the “what could go wrong” question. Tim Maughan has taken a look at “smart cities,” and the general digitization and “algorithmization” of our society, and turned it into a truly captivating, haunting, and unfortunately very convincing near-future scenario. Infinite Detail is set in Britain pre- and post-crash, and offers brilliant observations about our society and where we may be headed, while at the same time telling a captivating story with some almost-mystical elements.

Mark Galeotti

Surrogate Warfare: The Transformation of War in the Twenty-First Century by Andreas Krieg and Jean-Marc Rickli. Everyone these days is scurrying around to answer the question of how conflict is changing, and ideally attach their chosen title to the new face of war (assuming it needs one). By focusing on the “surrogacy” of modern Western operations, the use of proxies from drones to local militias (which effectively means intervention operations rather than potential peer conflicts), Krieg and Rickli may not have all the answers, but they ask a lot of the right questions, and do so eminently readably.

Gideon the Ninth by Tamsyn Muir. We all need something to distract us in these gloomy pandemic days. What better than a tale of far-future gothic necromancy, skeleton-painted nuns, some judicious mass murder as an aid to conception, and a universe built of bones? This is not a WH40K gore-fest (although there is gore aplenty), but a splendidly imaginative, witty, and beautifully written piece of science fantasy.

Francis J. Gavin

One of my pandemic projects was to revisit the great Oxford University History of the United States series — an extraordinary, multi-decade project where the best historians are commissioned to provide comprehensive, synthetic accounts of crucial periods (and subjects) in the history of the republic. During a dark and troubling 2020, it was strangely comforting (if not reassuring) to recall that the United States has, from its earliest beginnings, faced deep challenges and crises before, including many that were self-inflicted. America’s history is steeped in racism, inequality, and violence as well as innovation, generosity, and political enlightenment; its leadership marked by political nobility and vain charlatanism; its engagement with the world bouncing back and forth between self-reliant isolation and desires to transform the world (often at the same time). My favorite volume in the series remains the first, James McPherson’s masterpiece Battle Cry of Freedom, far and away the best book on the national crisis that, in many ways, continues to shape our fragmented national identity. But a near runner-up was Daniel Walker Howe’s magisterial What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848. I came away disliking Andrew Jackson more than ever (and puzzling over what Arthur Schlesinger Jr. saw in him decades ago), while also seeing obvious contemporary parallels in his cronyism, lack of respect for norms and civility, prejudice, and jingoism. Yet, it was also a period of remarkable change, mixing religious revivalism with technological upheaval, profound demographic change, and massive economic growth, filled with some of the most political colorful and influential political and cultural figures of our nation’s history.

T.X. Hammes

Since we are once again in a period of great-power competition, I strongly recommend reading all three parts of Ian W. Toll‘s trilogy on the Pacific War: Pacific Crucible, The Conquering Tide, and Twilight of the Gods. Toll provides new insights into the diplomatic, domestic political situation (on both sides), and the military aspects of this titanic struggle. Toll’s writing is so engaging the reader gets deeply involved with the personality, strategies, and tactics of the conflict. The analysis of the logistical issues and strategic terrain of the Pacific should inform today’s strategists as they grapple with the competition with China.

Doyle Hodges

The Chinese Typewriter: A History by Thomas Mullaney. This book was not what I expected. I went in thinking I was going to read a fascinating object history along the lines of Salt, or Longitude. What I found instead was a fascinating blend of sociology, information theory, and history. Mullaney explores not so much the history of the Chinese typewriter, as how Western conceptions of the merits of alphabetic versus symbolic languages were distilled in the technology of the typewriter, and the various ways in which Chinese and Western innovators adapted China’s non-alphabetic language for its now-ubiquitous use in keyboard-based information technologies.

The Red Trilogy (The Red, The Trials, and Going Dark) by Linda Nagata. I was unfamiliar with Nagata’s work until I read The Last Good Man in preparation for a War on the Rocks podcast on recent military science fiction. The Red trilogy is a powerful and fascinating exploration of themes related to civil-military relations, technology and humanity, and the military-industrial complex. Nagata creates engaging characters and a plausible near future to explore these issues, while telling a great story along the way.

Frank Hoffman

Shields of the Republic: The Triumph and Peril of America’s Alliances by Mira Rapp-Hooper. To appreciate the importance of alliances to U.S. national security past and present, this is the most concise history and prognosis you will ever see.

The Culture of Military Organizations edited by Peter R. Mansoor and Williamson Murray. If you want to understand the internal operating code of a military organization, and why it acts and functions the way it does, you need to penetrate its culture. An eclectic collection of historical studies, edited by two eminent military historians.

The Kill Chain: Defending America in the Future of High-Tech Warfare by Christian Brose. Hard-hitting critique of the U.S. military and its glacial preparations for the next war. Provocative and saturated with a sense of urgency but techno-centric.

Kimberly Jackson

Wine and War: The French, the Nazis and the Battle for France’s Greatest Treasure by Don and Petie Kladstrup. As a national security professional and a student of wine, I was thrilled to find this book. It’s a highly entertaining, fast read about how World War II affected winemakers and the entire wine industry in France, and likewise about how wine played a substantial role in the outcome of the war in multiple ways. It was the first book I finished in 2020, and ended up being my favorite of the year.

You Think It, I’ll Say It by Curtis Sittenfeld. I believe the short story is perhaps the best measure of someone’s storytelling ability, yet entirely undervalued. Sittenfeld’s 2018 collection is a masterful example. Her stories are smart and engrossing, each featuring complex and deeply human characters that are immediately relatable. Sittenfeld’s stories accomplish exactly what a short story should: leave you wishing it could have been a complete novel just to spend more time with it, but satisfied in its brief, well-crafted arc.

Rebecca Lissner

The Glass Hotel by Emily St. John Mandel. A perfect quarantine read, this immersive novel will draw you into its multiple, interwoven narratives of family dramas, the construction and destruction of wealth, and addiction.

The Chessboard and the Web by Anne-Marie Slaughter. In a world of pandemics, climate change, and rapid technological change, Slaughter’s prescient 2017 book is an important reminder that there’s more to grand strategy than great power competition.

Tanvi Madan

How India Became Democratic: Citizenship and Making of the Universal Franchise by Ornit Shani. The last few years has made evident that democracy cannot be taken for granted and is a work in progress that needs constant tending. Shani’s book is a meticulously researched account of what it took to help establish the largest democratic experiment in history. It covers the challenges faced by multi-ethnic, multi-religious, multi-lingual India’s founding fathers and mothers in turning every Indian into a voter — even before India’s constitution came into being. The book is also a much-needed reminder that when countries put their minds to it, they can take on the most massive undertakings and emerge successful. If you need a dose of optimism amid the 2020 doom and gloom, this will help.

An Infamous Army by Georgette Heyer. I’ve been re-reading books that I like while I’ve been housebound during the pandemic; those include a number of books by underrated British author Georgette Heyer, known for her Regency-era novels. Less known about is the amount of historical research and detail that went into them. An Infamous Army is perhaps the prime example of that, with its depiction of the Battle of Waterloo considered so accurate that it was assigned at the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst. Want to escape this year? These books will help transport you back a couple of centuries to battlefields and ballrooms.

Melanie Marlowe

In After Trump, Bob Bauer and Jack Goldsmith, well-known former executive branch lawyers, look at a number of ethical and legal topics highlighted by recent presidential behavior. While Trump has brought fresh attention to issues such as pardons, tax disclosure, financial conflicts of interest, and war powers, the history Bauer and Goldsmith provide makes it clear that discussion about reforms, a word I am wary of (will the cure be worse than the disease?), is overdue. If you are a dreamy idealist, this book may not be for you. The authors understand practical politics and only consider proposals, some incremental, they believe could get bipartisan support. I don’t agree with every suggestion, but the time for this conversation is now, and this book is an important contribution to the discussion.

David Maxwell

Becoming Kim Jong Un: A Former CIA Officer’s Insights into North Korea’s Enigmatic Young Dictator by Jung H. Pak. For those who heed the wisdom of Sun Tzu to know the enemy, Pak offers us the only comprehensive biography and assessment of the most despotic leader in the 21st century: the supreme leader of North Korea, Kim Jong Un. There are few who have studied the life (and education) of Kim in such great depth. It is imperative that strategists and policymakers have an understanding of Kim’s personality, his motivations, what influences his decision-making, and his desires. Although recent books touch on Kim’s life and background, there is no work as comprehensive and detailed as Pak’s critically important book.

Phoenix Rising: From the Ashes of Desert One to the Rebirth of U.S. Special Operations by Keith M. Nightingale. There have been many accounts of Operation Eagle Claw and the failure at Desert One in Iran. Most know that seven years after the failure, the U.S. Special Operations Command was born to give the nation a combatant command to integrate and employ the joint special operations forces from across the services. What is unique about this book is that it was written by an insider working at the Pentagon, a staff action officer, who contributed directly to planning the rescue and then later building on lessons learned to make U.S. special operations the premier force it is today. This book should be read by all staff action officers not only for the history, but to see how complex ad hoc missions are coordinated in extremis. Action officers in the Pentagon are too often unsung. This book tells their story and why they are instrumental in planning and executing operations. The name “Iron Major” is not given lightly.

Mike Mazarr

Weapons of Math Destruction: How Big Data Increases Inequality and Threatens Democracy by Cathy O’Neil. One of the best, and most daunting, assessments of the most wide-ranging security issue we face — the role of socially-shared information networks, and the need for standards of security and knowledge that enhance rather than undermine democracy and equality. O’Neil focuses on one aspect of the larger issue: the way companies and governments are using algorithmic modeling and other techniques to make automated choices for individuals and society. It is a potentially dangerous trend, and few are paying attention.

The Emperor’s New Road: China and the Project of the Century by Jonathan E. Hillman. Amid the hyperventilating about the Belt and Road Initiative — and China’s broader search for global “influence” — few studies go beyond the top-level numbers or ambitions to dissect the Belt and Road Initiative’s actual results on the ground. Hillman’s study is one of the best of a new set of analyses trying to do just that. Based on engaging insights from field research as well as deep familiarity with the data on the Belt and Road Initiative, he makes clear that China is not immune to the challenges any great power or large investor faces in developing nations, and describes both the potential and great risks involved in the project. A first-rate blend of analysis and journalistic reporting from the front lines of economic statecraft.

Bryan McGrath

George Orwell by Gordon Bowker. A biography of the talented, troubled, deeply flawed man whose last two books (Animal Farm and 1984) are read by anyone wishing to consider themselves literate in the English language. My main discovery in reading it is that I have some additional Orwell reading to do.

Never Trump: The Revolt of the Conservative Elites by Robert P. Saldin and Steven M. Teles. A deeply researched inquiry into the motivations of dedicated Republicans and conservatives (they are not the same thing) who turned on the GOP nominee in 2016. The national security putsch started right here at War on the Rocks.

Megan Oprea

Middlemarch by George Eliot. Take a break from all things political and submerge yourself in the world of a fictional, 19th-century British town and the many intrigues of its inhabitants. Eliot describes not only the happenings of the town and the politics of the time, but also comments on the human condition and the difficulties we can bring upon ourselves through idealism.

1774: The Long Year of Revolution by Mary Beth Norton. Norton’s latest book goes deep into the goings-on in the American colonies in late 1773, 1774, and early 1775. One of the unique characteristics of this description of the early years of the American Revolution is that Norton examines not just the writings and actions of those who opposed the Crown, but those of the loyalists as well. She offers a more nuanced, and highly detailed, view of this long, tumultuous year.

Douglas Ollivant

Undoing the Revolution: Comparing Elite Subversion of Peasant Rebellions by Vasabjit Banerjee. In this well-written first book of comparative politics, Vasabjit Banerjee compares 20th-century peasant rebellions in Mexico, India, and Rhodesia/Zimbabwe. Certainly, at the least the first two of these are understudied by American scholars of the topic. Banerjee concludes that peasant revolutions succeed only when out-of-power elites join them, bringing the resources necessary to overthrow an existing state. However, then in the post-revolution bargaining, the interests of the peasants (who provided the bulk of the revolutionaries) are subverted by the new, no longer out-of-power elites. A fresh look — using relatively unfamiliar cases — that adds real nuance to our understanding of how revolutions unfold.

The Man Who Ran Washington: The Life and Times of James A. Baker III by Peter Baker and Susan Glasser. The definitive study of one of the giant figures of American politics in the late 20th century. Incredibly detailed and insightful with a prose style that reads like a novel (okay, a dense novel — but still!). In some ways a retelling of U.S. political history from Nixon through Bush 43, through the eyes of one of the major “players,” courtesy of the most prominent team of husband-wife journalists in Washington.

Iskander Rehman

Between Two Fires: Truth, Ambition, and Compromise in Putin’s Russia by Joshua Yaffa. One of the most poignant depictions of the morally corrosive effects of everyday life under authoritarianism. Superbly written, deeply humane, and a meticulous dissection of Putin’s Russia.

The Shadow King: The Life and Death of Henry VI by Lauren Johnson. If there is one area where the United Kingdom continues to reign supreme, it is in the production of brilliant young historians. Johnson’s empathetic yet nuanced biography of one of England’s more ill-starred monarchs is a veritable tour de force. Henry VI, who was crowned king in his mere infancy following the premature death of his belligerent, overachieving father, was a well-meaning but ultimately tragic figure — one destined to bear witness to the steady unraveling of England’s military gains in France, and to its eventual defeat in the Hundred Years War. Plagued by episodes of catatonic schizophrenia in an era which had little tolerance for (or understanding of) mental illness, his fractured psyche serves as a form of funhouse mirror to the rising factional discord and social unrest within his deeply troubled kingdom. These fissiparous tendencies would eventually lead to the devastating Wars of the Roses, and to the hapless monarch’s untimely end. Johnson’s biography sheds welcome light on a largely underexamined historical figure, all while providing a fascinating window into a pivotal period in English and European history. For students of statecraft, it is rife with insights on the nature of protracted warfare, the challenges of alliance management, and the perils of military overextension.

Usha Sahay

Plutopia: Nuclear Families, Atomic Cities, and the Great Soviet and American Plutonium Disasters by Kate Brown. Historian Kate Brown expertly tells the story of early plutonium production efforts in the Soviet Union and in the United States. She illustrates how social, political, and financial imperatives led officials to construct systems and practices for the production of nuclear fuel that today seem bizarre, absurd, or appalling – from the deliberate effort to put the “nuclear family” at the center of these atomic towns to the shockingly negligent attitude toward what was almost certainly widespread radiation poisoning on both sides. The juxtaposition of the two stories is a smart way of highlighting the similarities that emerged as two very different societies sought to tackle a similarly daunting scientific and technical problem. Especially for readers whose day jobs tend to focus more on “hard” national security issues, Brown’s focus on the scientific and social aspect of the arms race – and on the people and communities who were affected – offers a useful corrective to the standard Cold War narrative.

Wild: From Lost to Found on the Pacific Crest Trail by Cheryl Strayed. This memoir, which many will know from the 2014 movie adaptation starring Reese Witherspoon, tells the story of a young woman who loses her mother and, grief-stricken, decides to embark on a difficult, months-long hike through the Cascade and Sierra Mountains alone, and with barely any training. Strayed is a beautiful writer, whom I first came to know through her “Dear Sugar” advice column and podcast. Her memoir beautifully combines ruminations on grief, a fun cast of fellow hikers whom she meets along the way, and a genuinely compelling and sometimes suspenseful narrative (there’s never any doubt that Strayed will survive the difficult journey, but she gets herself into a number of perilous situations that will keep you turning the pages). Above all, I found Wild to be a thought-provoking reflection on solitude. It shows that being alone can offer the opportunity to be creative, learn about oneself, and heal from grief and trauma, but also offers a reminder that all journeys in life, however emotional or mountainous, are defined in some way by our relationships with, and the kindness of, the people around us.

Kori Schake

Tecumseh and the Prophet: the Shawnee Brothers Who Defied a Nation by Peter Cozzens. This is a riveting transportation to the American frontier at the last moment that Native Americans might have had the ability to turn back, or at least contain, European conquest of North America. The combined efforts of Tenskwatawa, who conjured a unifying religion exclusive to Native Americans that layed the foundation for unity, and Tecumseh, who fostered the alliances and led the battles, nearly overturned American control of half the United States. William Henry Harrison, who’d negotiated with Tecumseh, described him admiringly as “one of those uncommon geniuses which spring up occasionally to produce revolutions and overturn the established order of things.” A great historical rendering of their near miss at overturning America.

The Daughters of Kobani by Gayle Tzemach Lemmon. Nobody tells the stories of women confronting an unexpected modernity better than Gayle Lemmon. Daughters charts the tragic arc of the fight against ISIL, U.S. reliance on Kurdish proxy fighters and the excellence of female freedom fighters as the backbone of the Kurdish force, and how their success as combatants changed their society. Their vitality pulses through the book, making our abandonment of them all the more heart-rending.

Image: icatchingdesign at Pixabay