Asia’s Looming Subsurface Challenge

From the 1950s until today, Russia’s dangerous Atlantic submarine force has represented the technological pacing threat for the U.S. Navy in the undersea domain. However, this trend is slowly changing. It will be the waters of the Pacific, not the Atlantic, where the U.S. Navy will be most sorely tested. In his 2016 posture hearing, Commander of U.S. Pacific Command Admiral Harry Harris noted that Chinese, Russian, and North Korean submarines constitute 150 of 200 submarines currently in the Pacific. Numbers only tell part of an increasingly ominous story. The trajectory of submarine investments made by these nations — and ten other Asia-Pacific countries — will create a far more dangerous undersea domain in the Asia-Pacific by 2030. Developing the policies and frameworks that will enable effective shaping of this environment must be started before the crisis hits.

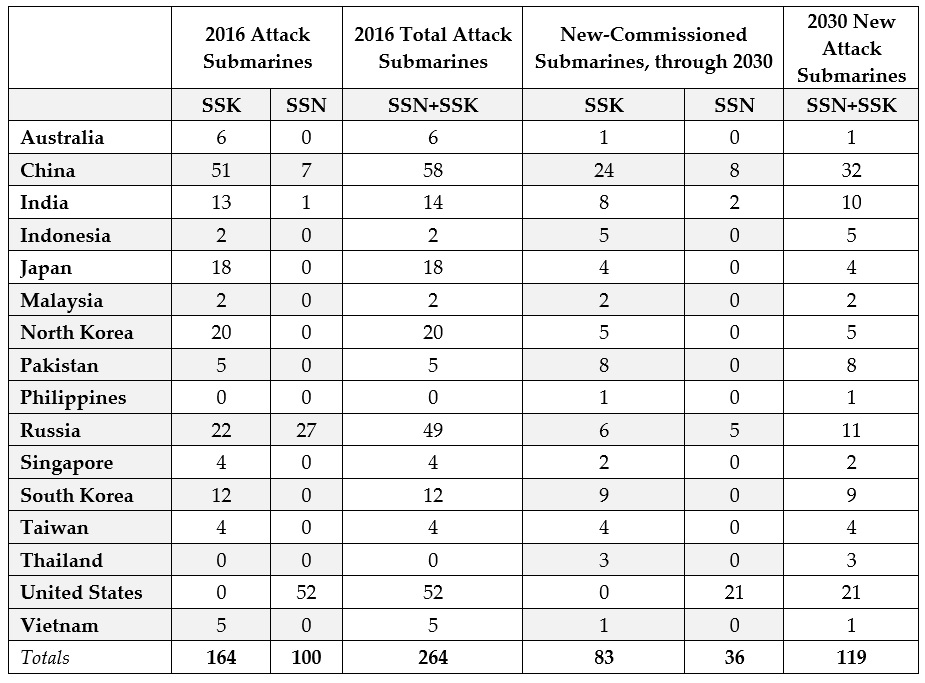

The recent unanimous award by the International Tribunal on the Law of the Sea and China’s vocal and active rejection of the legitimacy of the decision bolsters the need for many countries in the region to have a credible submarine deterrent force. Not surprisingly, countries throughout the region have been working for some time to bolster their submarine forces and others are considering establishing such capabilities. Both trends are captured in figure one below, tracing current and 2030 expected total diesel (SSK) and nuclear (SSN) submarine fleet numbers. Countries in Asia are seeking credible deterrence forces as their confidence wanes regarding the peacefulness of China’s rise and the reliability of U.S. commitment to preserve stability.

Submarine Missions

Submarines can be used to defend a nation’s territory and to project power abroad. Most nations in maritime Asia are acquiring submarines for their sea denial capabilities to credibly deter larger, more militarily capable adversaries. Submarine warfare is inherently asymmetric, imposing potentially large costs on any potential adversary. The mere threat of submarine activity can dramatically affect an adversary’s planning considerations. In peacetime, submarine forces accomplish these goals by monitoring the naval activities of other countries, protecting their country’s sea lines of communication, and, for a small number of nations, providing a sea-based nuclear deterrent. A well-equipped submarine force operated by a highly trained crew provides an exceptionally capable and flexible platform for these many missions.

Geography in the Asia-Pacific

The maritime geography of the Asia-Pacific — and its centrality to the U.S. and global economy — has powerful implications for how submarines can be employed throughout the region. The first island chain, running from Japan through Taiwan to the Philippines, forms a natural barrier that China fears may “bottle up” its naval forces. Similarly, the relatively small number of approaches through the islands provides China’s increasingly capable missile force a relatively small number of aim-points should it seek to counter foreign countries’ navies. Key chokepoints such as the Malacca, Lombok, and Sunda Straits further complicate access to the region (Figure 2, below).

Submarine forces are also affected — in some instances, dramatically — by the varied undersea geography (technically, bathymetry) of maritime Asia. The region includes shallow seas such as the Yellow and East China Seas, extremely deep areas such as the Philippine Sea, and complex littoral seas with characteristics of both. Nuclear-powered submarines reign supreme in deep, open waters but fare worse in the congested shallow waters throughout Southeast Asia. Here, smaller diesel-electric vessels can use the varied undersea topography to their advantage. The shallow waters of Asia’s littoral zones combined with regional chokepoints increase a submarine’s inherent sea denial capability.

Platform + People = Capabilities

More than almost any other naval asset, submarines require complex and regular maintenance and a highly trained crew to realize the platform’s potential. Submarines spend most of their lives in a high-corrosion, high-pressure environment and rely on exquisitely maintained equipment to ensure silent running. Many nations in the Asia-Pacific are acquiring relatively advanced foreign submarines because they lack a robust indigenous shipbuilding capability. This does not bode well for the longevity of their submarine capability without relying heavily on foreign contractor support. For example, the French firm DCNS now provides comprehensive support to Malaysia in the wake of crippling domestic maintenance challenges after its procurement of two Scorpene submarines built by the firm.

In addition to maintenance issues, building a force of highly trained submariners is challenging for small navies. More than basic bureaucratic and training infrastructure, small navies will find it almost impossible to create a proficient submariner corps. Navies with only one or two operational submarines will have to compensate for less underway experience to develop the necessary skills in both enlisted personnel and officers. Schoolhouse and training pipeline shortfalls are not unique to Asian nations but nonetheless will have to be overcome by nations across the region. Without a highly trained crew, advanced submarines are unlikely to be effective.

Current and Future Submarine Capabilities

Despite the long build times and complex operational requirements, Asian countries are expected to acquire over 100 submarines by 2030. In many cases, old submarines will be retired and replaced with newer, more capable vessels. Other countries are looking to either establish a new submarine force or expand their fleet. These decisions, especially taken in aggregate, suggest that the nations of the Asia-Pacific do not believe that the security and stability of their region remains on a positive trajectory.

Looking to the future, an increase in the number of submarines will not necessarily equate to cutting-edge submarine capabilities nor will it necessarily give nations the capabilities they seek. Most SSKs lack the speed necessary to conduct aircraft carrier escort missions and lack the endurance to operate in the vast expanses of the Pacific or Indian Oceans. To understand the future role and impact of attack submarines in the Asia-Pacific, one must examine the current and future submarine forces in the region. (Ballistic missile submarines — SSBNs and SSBs — are important for deterrence and second-strike nuclear capability but are beyond the scope of this article.)

China, Russia, and North Korea

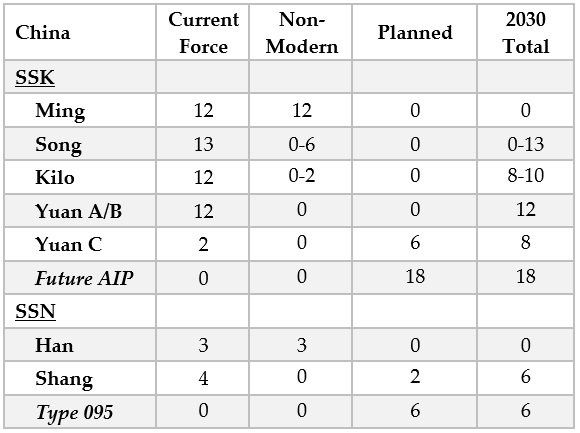

The Chinese attack submarine fleet comprises 58 attack submarines of 6 different classes: four diesel-electric (SSK) submarine classes — the Type 035, Kilo, Type 039 and 039A classes (Ming, Kilo, Song, Yuan, respectively) — as well as two nuclear attack submarine (SSN) classes, the type 091 and 093 classes (Han and Shang, respectively). The table below provides additional information about the number and types of vessels in each class.

Of China’s current fleet of attack submarines, between 12 and 20 are unlikely to be operationally effective against a technologically advanced foe because of their age and questionable quality —namely the Ming and Han classes, early Kilo class, and possibly early models of the Song class. As a result, China’s current fleet of submarines likely includes between 38 and 46 modern attack submarines. The vast majority are conventionally powered. The most recent Yuan-class are believed to be outfitted with air independent power (AIP) systems, to incorporate quieting technology from Project 636 Kilo-class submarines, and to be capable of launching anti-ship cruise missiles. In addition, China appears to be improving its ability to produce SSNs with the Type 093 Shang class SSN. Two are currently in service, with an additional three vessels awaiting commissioning.

China is expected to construct and commission around 32 additional submarines over the next fifteen years, including improved Shang-class SSNs and a long-rumored third-generation SSN, the Type 095. Based on open-source information and our analysis, we believe that China will field a modern submarine force of approximately 60 SSKs and SSNs by 2030, with the majority of these being advanced conventional submarines with AIP. With appropriate crew training, these will represent a highly capable submarine force that provides longer submerged endurances and increased acoustic performance, particularly within the first island chain and in the South China Sea.

In addition to concerns about China’s submarine investments, Admiral Harris expressed his concerns about Russian and North Korean submarine fleets. The U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence identifies 22 submarines in Russia’s Pacific fleet. Of these, it is likely that only one to two SSBNs, three to five SSNs/SSGNs, and five SSKs are operational. Analysts believe that Russia has prioritized its Pacific fleet, but it is unclear if this prioritization will continue in light of increased tensions in Eastern Europe and budgetary shortfalls.

By comparison, Pyongyang currently claims approximately 70 submarines, none of which should be considered modern nor will its capability or capacity likely improve in the future. However, as is seen in the 2010 sinking of the South Korean navy ship Cheonan, North Korea’s rudimentary submarines can nonetheless be lethal in the Korean littorals.

India and ASEAN countries

New Delhi currently fields a fleet of 14 operational submarines, predominantly Sindhughosh (Kilo) and Shishumar class SSKs (Type 209). Built under contract with the Soviet Union/Russia and Germany, respectively, this fleet is approaching the end of its life. Over the next two decades, India plans to build an additional five to eight Kalvari class SSKs, French Scorpene SSKs built under a technology transfer agreement. The lead ship was launched several years behind schedule in May 2016. The Kalvari will be complemented by the first Indian-designed and built nuclear submarine, the 6,000-ton Arihant SSBN, making India the sixth country operate a SSBN. This indigenous SSBN will likely serve as a technology testbed for a future indigenous SSN.

Vietnam is one of two ASEAN nations with a significant undersea warfighting capability. With five vessels currently in service, the Vietnamese Navy is in the final stages of acquiring its sixth Project 636 Kilo-class submarine from Russia. These vessels provide a powerful deterrent signal in the congested and contested South China Sea. Singapore is the other ASEAN nation proficient in submarine warfare. It operates four Swedish built submarines of the Archer and Challenger classes. Despite their relative age, the vessels are regularly upgraded and overhauled. Singapore plans to acquire two 2,000-ton Type 218SG submarines to replace the older Challenger-class vessels.

Most other Southeast Asian nations face challenges keeping their respective submarine programs on a steady developmental trajectory due to technological, political, and/or fiscal reasons. Indonesia has flirted with sourcing from multiple countries — France, Russia, and South Korea — as it eyes an expansion of its fleet from two to 12 SSKs. Efforts in Malaysia to increase its submarine fleet have been plagued by corrupt politics and poor manufacturing. As a result, the first Scorpene delivered has experienced a chronic maintenance shortfall. Thailand and Pakistan have negotiated deals with Beijing for modified export versions of the Yuan class Type 039A. For Thailand, this would be the first time it has acquired submarine capabilities, and it remains unclear the extent to which either nation could effectively operate such vessels.

Australia, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan

Australia operates a fleet of six Collins class vessels but has faced considerable recruitment and availability issues. Canberra announced that it will replace its aging Collins class vessels with 12 Shortfin Barracudas, an AIP submarine, in an ambitious $38.5 billion program that combines the French firm DCNS with local Australian industry. The first vessel will be commissioned in the 2030s and outfitted with U.S. combat systems and, potentially, unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs). The Barracuda fleet is expected to stay in service through 2070. While Tokyo may have lost the bid to supply Australia with its future fleet, Japan continues to invest in its own force, operating 18 SSKs split between the older Oyashio class and the more recent Soryu class. The Maritime Self-Defense Force plans to add another four Soryus and establish a sixth submarine division at Yokosuka. In South Korea, the Republic of Korea Navy operates 14 German-designed SSKs/SSPs, the most recent of which are equipped with AIP systems. Plans call for an additional nine 3,000- to 4,000-ton vessels to be commissioned beginning in the mid-2020s and potentially equipped with a short-range ballistic missile system. Even Taiwan has plans to swap its vintage Dutch Zwaardvis and U.S. Tench and Balao class vessels for four to eight indigenously procured submarines, a plan that may be more symbolic than feasible given a stagnant defense budget and dearth of technological expertise.

Even as countries in the Asia-Pacific are investing to recapitalize or to grow their submarine forces as a deterrent capability in uncertain times, the United States, long the pre-eminent naval power in the region, is now facing 14 years of declining numbers in its submarine force. The planned attack submarine force shrinks from 53 boats today to 41 boats in 2028 before slowly returning to the current level of 51 submarines in 2046.

Current investments in advanced technologies such as UUVs may offset the reduction to some degree. Some of this cutting edge technology resides in the private sector. As a result, the barriers to access (through purchase or theft) the technology are lower than for the traditional “crown jewels” of the U.S. nuclear submarine enterprise. The time it takes other countries — allies or adversaries — to approach, gain, or exceed parity with the United States will likely be reduced. However, due to the complexity of underwater operations and systems this shrinking delta is less pronounced here than in other domains.

Policy Implications

For the United States and countries throughout the Asia-Pacific, submarines represent an important signal of national intent — to deter and, if necessary, to compel other actors from taking undesirable actions. The growth of submarine fleets throughout the region is a signal that regional states are hedging against a more competitive future environment.

Even as Washington renews its focus on Russia’s submarine force, significant advances in China’s submarine force and declining numbers in the U.S. fleet will be the greatest complicating factors for U.S. Navy planners and policymakers. Further, advances in technology have resulted in submarines that are increasingly multi-mission. Attack submarines are now tasked with far more than shadowing an adversary’s ballistic missile submarines or surface fleet. Modern U.S. SSNs are increasingly used for intelligence collection, special forces activities, crisis response, and conventional deterrence. The compression of many missions into a shrinking number of platforms will result in a complex set of operational and political signaling tradeoffs for both military commanders and political leadership.

The competition between the U.S. regional combatant commanders in Europe, Asia, and the Middle East for these important assets will only become more intense with time. Short of significant breakthroughs in UUVs — including with their command and control, endurance, and survivability — there will be no easy fixes to this shortfall.

Increased partnership, especially with highly capable allies such as the United States has in Japan and Australia, could contribute to an effort to buy down risk. However, any risk mitigation will not occur in a way consistent with Pentagon parameters, therefore necessitating a new line of thinking from those responsible for oversight of the Defense Department’s planning process.

The Navy should not assume that increased shipbuilding budgets alone will solve the coming shortfall. Rising personnel costs and broad downward pressure on end-strength (the total number of personnel in the force) will make recruiting and maintaining the personnel necessary to crew and maintain additional submarines more difficult, even if additional shipbuilding dollars become available. Similarly, the emergence of even extremely capable UUVs is unlikely to offset the diminished number of U.S. submarines in the near to mid-term, given the complexity of fielding such new and complex platforms in sufficient numbers.

The naval investments in the Asia–Pacific, especially in submarines, are setting the stage for a dangerous future both on and below the waves. The growing number of countries operating submarines will create an increasingly contested and congested undersea domain. Without changes to the current trajectory of U.S. investments, four broad trends will erode U.S. dominance in this domain.

First, more submarines operated by more countries will increase the operational risk of an undersea incident with unclear escalation dynamics. Second, the relatively rapid spread of advanced diesel submarines is directly challenging U.S. undersea supremacy. Nations do not need to achieve overmatch as the Soviet Navy once sought. Instead, they seek only local dominance as enabled and enhanced by undersea geography. Third, falling numbers of U.S. submarines (and consequently, submariners) will decrease U.S. opportunity to engage with and shape the direction of submarine forces globally, and especially in the Asia-Pacific where submarine forces are still nascent. Fourth, the decreasing size of the U.S. submarine fleet will hinder the creation of a theater anti-submarine warfare framework that links multi-national capabilities together to meet shared challenges.

Each of these areas requires greater examination — and in public, not just Navy, channels. Given the trajectory of future submarine capabilities in the Asia-Pacific and an initial understanding of the generation of capabilities, now is the time to undertake a rigorous analysis of the challenges facing the U.S. Navy in the undersea domain and how these challenges can be addressed through investments and partnerships.

John Schaus is a fellow in the International Security Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), where he focuses on Asia security challenges. Lauren Dickey is a PhD candidate in War Studies at King’s College London and the National University of Singapore. Andrew Metrick is a research associate in the International Security Program at CSIS.

Note on sourcing: Tables used in this article have been compiled drawing on data from a number of sources including: U.S. Navy documents; “The PLA Navy: New Capabilities and Missions for the 21st Century” by the Office of Naval Intelligence; published reports by U.S. government analysts; The Military Balance by the International Institute of Strategic Studies; open source articles from regional press and think tanks; authors’ analysis of historical submarine acquisition patterns in the U.S., Russia/U.S.S.R., and China; and authors’ analysis of submarine shipbuilding infrastructure in the United States and China.