Join War on the Rocks and gain access to content trusted by policymakers, military leaders, and strategic thinkers worldwide.

The Battle of Marengo was the culmination of Napoleon’s campaign in Italy in May–June 1800. It completely unraveled the string of Second Coalition victories across the peninsula that began the year before. The battle is notable for Napoleon’s initial underestimation of his enemy. Only timely reinforcements and Austrian hubris won him the day. Napoleon recounted the words of Gen. Louis Desaix at Marengo, that “the battle is completely lost; but it is only two o’clock and we still have time to win another today.”

Marengo became a foundational pillar in the Napoleonic legend, and from the moment victory was achieved, Napoleon rewrote events to erase any mistakes he had made that nearly cost him victory. In the two centuries since the battle, historians have regarded Marengo as a critical victory for Napoleon that reestablished French power in northern Italy. Yet, the battle failed to conclude the War of the Second Coalition until six months later, with the defeat of the Austrians at Hohenlinden in Germany. Indeed, the Marengo campaign demonstrates both Napoleon’s strategic and operational brilliance, yet his overconfidence almost cost him victory on the battlefield and potentially his political power. The battle is a cautionary tale of assuming the enemy will act as you desire and, as importantly, that a well-led army of experienced troops can turn defeat into victory if the enemy becomes overconfident and makes mistakes in the process.

The French Strategic Crisis

When Napoleon returned from Egypt in October 1799, he found the strategic situation disastrous. In July 1798, he had left France with his expeditionary force after securing an end to the War of the First Coalition (1792-1797). While Napoleon campaigned in Egypt in the spring of 1799, however, a Russo-Austrian army under Field Marshal Alexander Suvarov swept through Italy, undoing all Napoleon’s gains. Coalition discord, however, led to the withdrawal of Russia from the war.

When Napoleon secured political power in the Coup of 18 Brumaire, (Nov. 9, 1799), the situation remained critical. The question remained: Where to strike — in Germany or Italy? Napoleon knew little of campaigning in Germany, but he was intimately familiar with Italy. Another problem was that there were few forces available for a spring campaign in 1800. The Army of Reserve comprised a hodgepodge of battalions of both veterans and conscripts. By the end of April 1800, there were just under 50,000 men in various stages of readiness spread across eastern France. In order to keep the Second Coalition guessing regarding the German or Italian theater, Napoleon assembled the Army of Reserve around the city of Dijon in east-central France in late March 1800. This position permitted easy access to the Upper Rhine, but also a route across the Alps into Italy. The latter was far more complicated logistically, but it remained possible. Ultimately, Napoleon decided that he would conduct his offensive in Italy, where he believed the strategic opportunities were the greatest for a decisive strike.

Gen. Michael von Melas, the Austrian commander in Italy, had clear orders from Vienna to eliminate the remaining French presence in Italy. Once achieved, he was to strike into France, take Nice and Savoy, and then march on Lyon. Melas was a solid officer. He had performed well in the earlier campaigns and continued to display skill in outmaneuvering Gen. André Massena in Piedmont. Massena commanded the remnants of the French army in Italy. He was a talented and seasoned officer who served under Napoleon in 1796-97 and won impressive victories in Switzerland in 1799. Yet, his position in the spring of 1800 was untenable. The Austrian army in Italy numbered more than 100,000 men, but only 82,000 were “mobile” troops. The remainder were in garrisons throughout northern and central Italy. Leaving a garrison in Turin, the capital of Piedmont-Sardinia, Melas deployed a Corps d’Observation, blockading Massena’s emaciated soldiers in Genoa, and marched west, along the French Riviera to Nice.

In 1796, Napoleon broke into northern Italy from the Mediterranean coast, but in 1800, he did not have the luxury of meeting Melas head on along the Riviera. At the beginning of May, the Army of Reserve, numbering 48,000 men, left Dijon and marched to Geneva and then into the St. Bernard Pass. The army comprised three corps under Gens. Jean Lannes, Claude Perrin Victor, and Louis Desaix, respectively. The cavalry was placed under Gen. Joachim Murat. Additional troops were required from Switzerland, and Gen. Jean-Victor Moreau reluctantly provided an additional 22,000 men to support the operation. Napoleon intended a grand manoeuvre sur les derrières (envelopment) in Italy. By marching through the St. Bernard Pass, the Army of Reserve would debouch via the Val d’Aosta and emerge from the Alps between Turin and Milan. Melas’ army in Nice would find its communications and line of supply cut by this movement.

Napoleon’s strategic maneuver paid off. His army crossed the Saint Bernard Pass on May 14-20 and arrived in Milan unmolested by June 2. He was convinced that by taking the Lombard capital, Melas would withdraw from Nice and abandon the siege of Genoa. While Melas did withdraw from southern France, the siege of Genoa ended with Massena’s surrender on June 4. Napoleon therefore spent little time in Milan and marched west with all haste seeking battle. The vanguard of the Army of Reserve comprised Lannes’ corps and Murat’s cavalry. On June 9, they encountered Austrian forces under Gen. Peter Ott at Montebello. The Austrian division suffered heavily and withdrew quickly toward Alessandria, southeast of Turin. The fortress city on the Bormida River then served as Melas’ headquarters. There, he concentrated his army, preparing to meet Napoleon with more than 30,000 men.

Napoleon’s success to this point made him overconfident. While shocked at Massena’s surrender of Genoa, he remained convinced that Melas would remain passive. It is rarely discussed that Napoleon made mistakes. The historiography and the Napoleonic legend tend to ignore them. This phase of the campaign demonstrates that the young first consul, merely 30 years old, made a near catastrophic error in assuming his enemy would do nothing. Melas however, had other plans, and as the French army marched toward Alessandria, he prepared to sortie from the city and attack Napoleon before he could concentrate his force. His staff calculated the number of troops in the Army of Reserve after a month of attrition and combat. Melas believed odds were in his favor. He established a fortified bridgehead on the east bank of the Bormida and organized his army into divisions. Melas methodically dictated their line of march so they could cross the river rapidly and overwhelm the French as they arrived.

Image: Department of History at the U.S. Military Academy Digital History Center

Battle by the Bormida

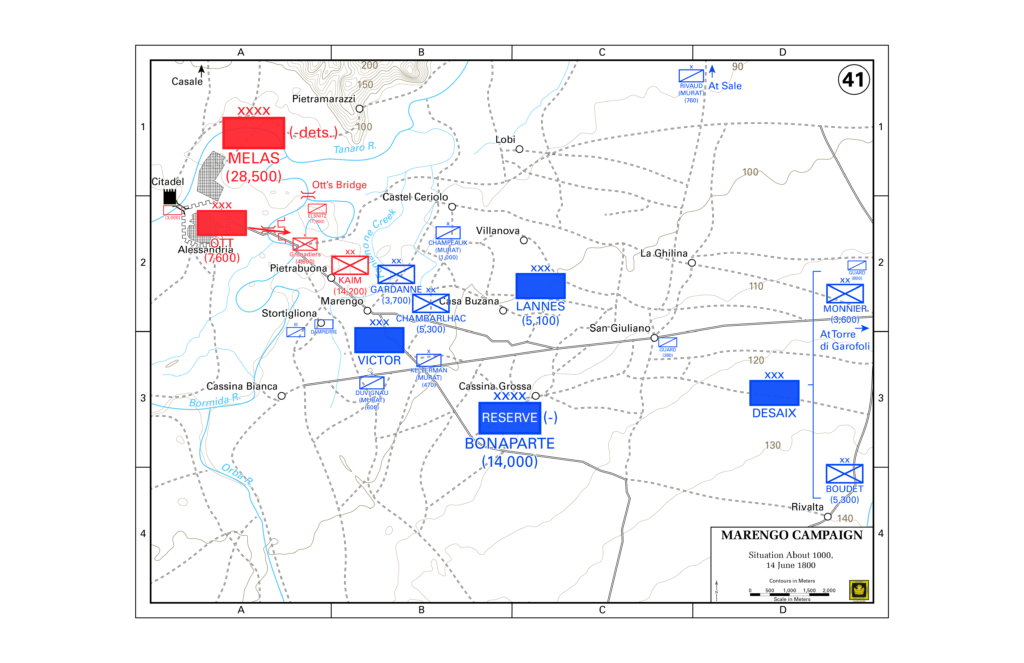

The carelessness of Napoleon’s approach on Alessandria is clear when he dispatched Desaix with part of his corps toward Genoa. Foolishly believing Melas would remain passive, he weakened his own army despite being merely a few miles from the Austrian main force. On June 13, Victor’s corps, supported by Gen. Kellermann’s cavalry, approached the Bormida and deployed around the town of Marengo. To his right rear camped Lannes’ corps, with Murat’s cavalry on his flank. Napoleon established his headquarters seven miles to the east at Torre di Garofoli. He had in reserve one division from Desaix’s corps and the Consular Guard. In all, the Army of Reserve at Marengo numbered 30,000 infantry and cavalry, roughly equal to Melas’ force.

The battlefield of Marengo is largely a plain that extends roughly ten miles between the Bormida and Scrivia rivers. It is good farmland, dotted with villages and a number of walled farms (cascina). The village of Marengo sits two miles from the bridgehead. Halfway between lies the Fontanone Creek, with marshy ground covering either bank. Two miles to the northeast of Marengo is the larger town of Castel Ceriolo, which formed the northernmost edge of the battlefield. The main road toward Genoa and Novi runs through the town and along the banks of the Scrivia. Two roads originate in Torre di Garofoli: the main one to Alessandria cut through San Giuliano, and the other that went to Castel Ceriolo to the northwest. The terrain therefore was good open ground for an 18th-century battle but provided no significant defensive ground beyond the Fontanone and its marshy banks. If Melas could move his divisions fast enough across the Bormida, and push the French beyond this topography, then Napoleon would be forced to defend in open ground where the Austrians had superiority in cavalry and artillery.

In the early morning hours of June 14, Austrian troops passed through the bridgehead on the Bormida. Victor deployed his divisions in depth, with Gen. Gaspare Gardanne’s troops closest to the bridgehead around the town of Marengo, with Gen. Jean Chambarlhac’s command, and Kellermann’s cavalry brigade a half mile to the southeast at Spinetta. Lannes’ troops were located to the northeast and beyond the Fontanone, too far away to support Victor.

The battle itself proceeded in four distinct phases: the Austrian offensive in the morning, the attrition battle until mid-afternoon, the French retreat, and finally, Napoleon’s counterattack in the evening.

At 7 a.m., the Austrian advanced guard under Gen. Johann Frimont made contact with Gardanne’s troops some distance to the west of Marengo. Although Melas had planned for a rapid movement of his divisions, the methodical character of Austrian march worked against time. The divisions crossed the river onto the plain, but they did not move quickly enough to engage and overwhelm the French forces to their front. This lethargy permitted Victor to organize Gardanne’s demi-brigades (regiments). The main Austrian assault did not commence until 9 a.m., and by that time, Victor was prepared to receive it. What followed was an hour of intense combat that delayed the Austrian advance, but at heavy cost to Gardanne’s division. Despite heavy losses, Victor’s troops held firm. Lannes’ forces arrived by 10 a.m. and extended the French line from Marengo northward. The marshy ground, and the bend of the Bormida, further complicated the Austrians’ ability to take advantage of their numbers.

By 11 a.m., the battle of attrition along the front took its toll on Victor’s corps. His line was pressed back sufficiently so that Austrian cavalry and a division under Gen. Andreas O’Reilly maneuvered around the French left flank. At this moment, Kellermann, son of the famed hero of the Battle of Valmy (1792) and a skilled cavalry commander, saw the threat and launched his three heavy regiments against the Austrian maneuver. The charge scattered the Austrian cavalry that was the immediate threat to Victor’s flank.

On the opposite flank, Ott marched upon Castel Ceriolo unmolested. By noon, he began the turning movement but ran into French cavalry and one of Lannes’ brigades. Over the next two hours, the Austrians pressed on front and flanks, and the fight devolved into an attrition battle. By 2 p.m., Victor and Lannes could no longer hold the line and were forced to withdraw.

The battle thus far had been fought without Napoleon present. He remained at his headquarters at Torre di Garifoli, approximately seven miles from Marengo. Although the sounds of battle were heard not long after the first cannon shots, Napoleon waited for reports. He sent Gen. Alexander Berthier — technically the commander-in-chief of the Army of Reserve but in reality, Napoleon’s chief of staff — to see the engagement and report back. It was not until 11 a.m. that Napoleon understood the gravity of the situation. He recalled Desaix who was marching south toward Novi and then mustered his reserve, Gen. Jean Monnier’s division, and the Consular Guard. Napoleon’s absence from the field — hours after it was clear that a major battle had developed — was another mistake made on that day.

The retreat of Victor’s and Lannes’ corps under heavy pressure gave Melas confidence that the day was won. Yet, not long after 2 p.m., Napoleon and the reserves came up. Monnier and the Consular Guard were dispatched to the right flank to attack Ott’s forces around Castel Ceriolo. The appearance of fresh troops diverted part of Melas’ columns pressing Victor and Lannes. Nevertheless, this merely stalled the pursuit but did not turn the tide of battle. Napoleon ordered a withdrawal. He had lost the battle and had to preserve his army. Melas observed the French retiring. After a long day, and suffering minor wounds, he handed command to Gen. Anton Zach and returned to Alessandria. Zach, however, was with the Austrian advanced guard, and Melas conveyed his order to Gen. Johann Konrad von Kaim, with whom he marched. Thus, there was initial confusion over who was left in command. Regardless, the Austrians appeared to have won the day.

Fortune favored Napoleon. Sometime after 4 p.m., Desaix arrived on the field ahead of his troops. Napoleon’s morning recall reached him around 1 p.m., and he immediately turned and countermarched back to Torre di Garofoli. Desaix’s corps had been divided in the morning, with Monnier remaining in reserve with Napoleon and Gen. Jean Boudet’s division marching on Novi. Desaix’s appearance on the field with almost 5,000 troops turned the battle. Napoleon attached Kellermann’s cavalry and Gen. Auguste Marmont’s massed battery of 18 cannons and howitzers.

By 5 p.m., the final phase of the battle commenced. Desaix’s attack met with significant resistance, but Napoleon’s combined arms of artillery, cavalry, and infantry shattered Austrian resolve. Amid the assault, Desaix was killed.

The Austrian army collapsed under the pressure. Over the next hour, troops fled in disorder toward the bridgehead over the Bormida and the safety of Alessandria. The exhausted French divisions pursued. By 10 p.m., the Army of Reserve reoccupied the positions they had held in the morning. The detritus of the Austrian army lay strewn across the field and by the redout protecting the bridge. Melas received word of the rout and observed the wreckage of his army as it hobbled back to the city. The next day, he reluctantly signed the Convention of Alessandria. This armistice ended hostilities temporarily and permitted Melas to withdraw his army to Venetia, thereby yielding Piedmont and Lombardy to France. Thereafter, the Austrian Emperor acceded to a general truce that lasted almost six months.

War and Politics

The lessons of Marengo are found in the immediate aftermath, as well as over the long term. The battle demonstrates the Napoleonic imperative that generals should “march to the sound of the guns.” Desaix’s actions clearly reflect that principle, and the marshals of Napoleon’s empire thereafter certainly did this more often than not. Indeed, the battle also provides lessons concerning overconfidence, hubris, and assumptions about what the enemy will or will not do. As Helmuth von Moltke the Elder stated, “No plan survives first contact with the enemy.” Napoleon’s assumptions about Melas’ inaction, and his overconfidence in his success to that point, clouded his judgement.

Napoleon failed to leave his headquarters in the morning when he first heard sounds of artillery around 7 a.m., and then two hours later when he received messages from Victor and Lannes about the events. Instead of mounting his horse and riding with reinforcements, Napoleon dispatched Berthier. His absence from the battlefield until 2 p.m. says much about his perceptions of his enemy and what he believed Melas would do. It is perhaps for this reason that Napoleon sought to rewrite the history of Marengo from the moment the battle had ended through his reign and into his exile (1800-1821). It remained an embarrassment, even if he had seized victory.

Moreover, the battle demonstrated the tactical superiority of the French army. Experienced division and regimental officers as well as non-commissioned officers enabled a flexibility on the field that was simply not present in the Austrian army. French regiments were able to change formation at will depending upon circumstance, from line (l’ordre mince) to column (l’ordre profond) and mixed order (l’ordre mixte) of two battalions in columns with a center battalion in line to provide fire and shock. Austrian battalions could only operate in the 18th-century style —a line formation for tactical combat. This limitation reduced the impact of Melas’ surprise offensive on the morning of June 14. All the planning carried out to rapidly attack the French on the plain failed because Austrian forces did not move rapidly and concentrate fires against the scant French forces. By the time sufficient numbers were available for a concerted push, Lannes’ and Victor’s divisions were already fully engaged. Even so, Melas managed to force Napoleon from the field by early afternoon, but his seeming overconfidence in victory provided opportunity for Napoleon to counterattack upon the arrival of Desaix’s division. The lesson here is clear. In Napoleon’s words, “There are many good generals in Europe, but they see too many things at once; as for me I see only one thing, namely the enemy’s main body. And I try to crush it.” Melas withdrew to Alessandria believing he had won the day leaving his subordinate Zach to leisurely pursue. Napoleon would not forget that he lost the battle in the afternoon, but won it back by night due to the enemy’s carelessness, and indeed his luck.

The Battle of Marengo effectively ended the War of the Second Coalition in Italy. Napoleon altered the strategic equation in a matter of five weeks. This victory, although “near run,” reinforced his reputation as one of the great generals of his age. It equally cemented his political power as first consul of France. This perhaps is the most significant aspect of the battle. It had dramatic ramifications both on and off the field. The battle is decisive for both what could have happened and what did not. The loss of Italy would have compromised Napoleon’s power that had only recently been achieved. He still had political enemies in Paris and rivals in the army.

Rewriting History

Napoleon needed a dramatic victory in Italy to secure his political position. The actual events at Marengo, which resulted from his mistakes, could not be exposed. It is for this reason that his Bulletin de L’Armée De Réserve (June 15, 1800), which was published and sent to France, gave a clear sense of the intensity of the battle but never its desperation. The events are presented with some colorful, imagined quotes and provide a wonderful example of Napoleonic propaganda. Yet, in the years following Marengo, Napoleon actively altered the record. Documents disappeared from the army archives, and the narrative changed. Napoleon could not make mistakes, and therefore, the official accounts were altered to place all fault on the Austrian command. David Chandler, the don of Napoleonic military history in the English-speaking world, addressed this quite well in a 1991 paper titled, “To Lie Like a Bulletin: An Examination of Napoleon’s Rewriting of the History of the Battle of Marengo.”

The significance of the battle to his political power meant that Napoleon continually reinforced his narrow-won victory into a decisive achievement. In his recollections on St. Helena, Napoleon is in full control of events, and despite his initial absence from the field, managed the affair from start to finish. The Marche de la Garde Consulaire à Marengo, composed by the head of the guard grenadier band in 1800, replaced La Marseillaise as France’s national anthem during the First Empire (1804-1815). Napoleon even named his favorite horse Marengo. He acquired it in Egypt, but rode him in 1800, and in many campaigns, including Waterloo. The battle therefore had a profound impact on the Napoleonic legend and was constantly revised over time by Napoleon, and later his admirers.

Why Marengo Matters

The Napoleonic legend succeeded in elevating Marengo to the same heights as the battles of Austerlitz, Jena, and Friedland. Yet, the historical truth reveals this to be an exaggeration. Nevertheless, the battle is instructive for operational and tactical leadership, training, and experience. The high quality of French leadership at all levels compensated for the mistaken assumptions concerning enemy actions. Despite overwhelming numbers of Austrian troops debouching from the Bormida bridges, French tactical proficiency, a keen understanding of the use of terrain, and the muscle memory of seasoned division and corps leadership prevented a disaster. For Melas, his methodical planning to rapidly cross the Bormida failed to consider the micro terrain beyond the bridgehead and the tactical limitations of his troops. Austrian officers and soldiers were veterans of many battles, yet their military system did not evolve since their first defeats by the French during the War of the First Coalition (1792-1797). The failure to adapt to a changing battlefield in the years prior to Marengo played a significant role in the lethargic offensive against Napoleon’s piecemeal divisions.

Victor and Lannes understood the situation despite Napoleon’s absence from the field for many hours. Concentration of force, delaying actions, and use of terrain held the Austrian line for half a day. Thus, the Austrians won an attrition battle in the first part of the day, rather than the intended one of annihilation. When Desaix countermarched to the field, he used initiative and the enduring principle of “marching to the sound of the guns.”

Fundamentally, Marengo was a battle of wills between two armies of equal numbers and quality. Napoleon’s subordinates, however, had fought with him for years and understood their commander’s intent, even without his presence on the field and lacking orders. Leadership, terrain, tactics, training, and morale all remain central to contemporary military operations, and thus Marengo remains instructive.

Frederick C. Schneid, Ph.D., is the Herman and Louise Smith Professor of History at High Point University in North Carolina. He specializes in the wars of the French Revolution and Napoleon as well as 19th-century wars. He has published extensively on these subjects. From 2023 to 2024, he served as the Charles Boal Ewing Chair of Military History at the United States Military Academy at West Point.

Image: Jean-Simon Berthélemy via Wikimedia Commons