Join War on the Rocks and gain access to content trusted by policymakers, military leaders, and strategic thinkers worldwide.

Russia has more friends than Western analysts like to admit, even three years into the Russo-Ukrainian War. While many have paid close attention to Russia’s beneficial partnership with Iran, the introduction of North Korea’s legions into the Ukrainian battlespace, or persistent materiel support from China, Russia’s other rising-power relationship is often underdiscussed — that of India.

The Russian-Indian relationship is both of longer duration and deeper history than those Russia has with its other key partners. It is also sometimes ignored as it does not extend to shared adversarial relations with the greater West. This is a mistake, as India is one of Russia’s self-identified civilizational friends. Furthermore, despite various ups and downs, the partnership has proven quite resistant to third-party pressures, including recently from the anti-Russian Western coalition.

The relationship has recently been in the news again as a result of President Donald Trump’s decision to place relatively high tariffs on India because of its purchases of Russian oil. These trade and tariffs issues have furthermore been caught up in the overall U.S.-Russian relationship that was discussed at the recent bilateral summit in Alaska. These developments raise the question of what drives Russian-Indian ties and how exactly the relationship has developed in recent years.

In fact, the overall Russo-Indian relationship has largely held steady in recent years. That this has been so is worth exploration. We offer that here and in expanded form in a new report we wrote that was recently published by CNA. Contrary to some expectations, even if war has strained the relationship in some respects, in others it has indeed improved. The direct effects of the Russo-Ukrainian War have been uneven, although there was a rapid and significant expansion in trade, primarily as a result of Indian purchases of oil from Russia. At the same time, India initially limited its political and military ties to Russia as it sought to maintain a relationship with Russia while avoiding alienating key Western partners.

The military components of the relationship have been the least improved, and in many cases have flatlined or slightly declined. Political ties are more diverse, with positive movement in symbolism, rhetoric, and a general resistance to accede to Western pressure. India has consistently refused to adopt the Western position on the war, instead issuing evenhanded calls for the end of hostilities. Both sides are using the relationship to highlight their focus on multipolarity and their shared desire to avoid excessive dependence on a single partner. Finally, it is clear that over the course of the war, as Western unity in policy toward Russia began to fray, India became less concerned about Western perceptions and reactivated its relationships with Russia in these spheres.

India does not see close ties with Russia and the United States as an either/or proposition, looking instead to maintain both at the same time. Both countries have been highly pragmatic in developing their military and economic ties, with the current geopolitical environment and circumstances dictating relative stagnation in military ties even as economic ties have grown rapidly. Both sides are looking to maintain a strong and stable relationship, even though it is not as close as Russia’s relationships with key partners such as China or Iran or India’s relationships with Western countries.

The Political Dimension

First, political ties between Russia and India continue to remain steady in most areas. In certain respects, they have even grown stronger in certain aspects since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Contrary to a prominent line of thought, the data we collected suggest that the political connections between Russia and India have not noticeably weakened since the onset of war.

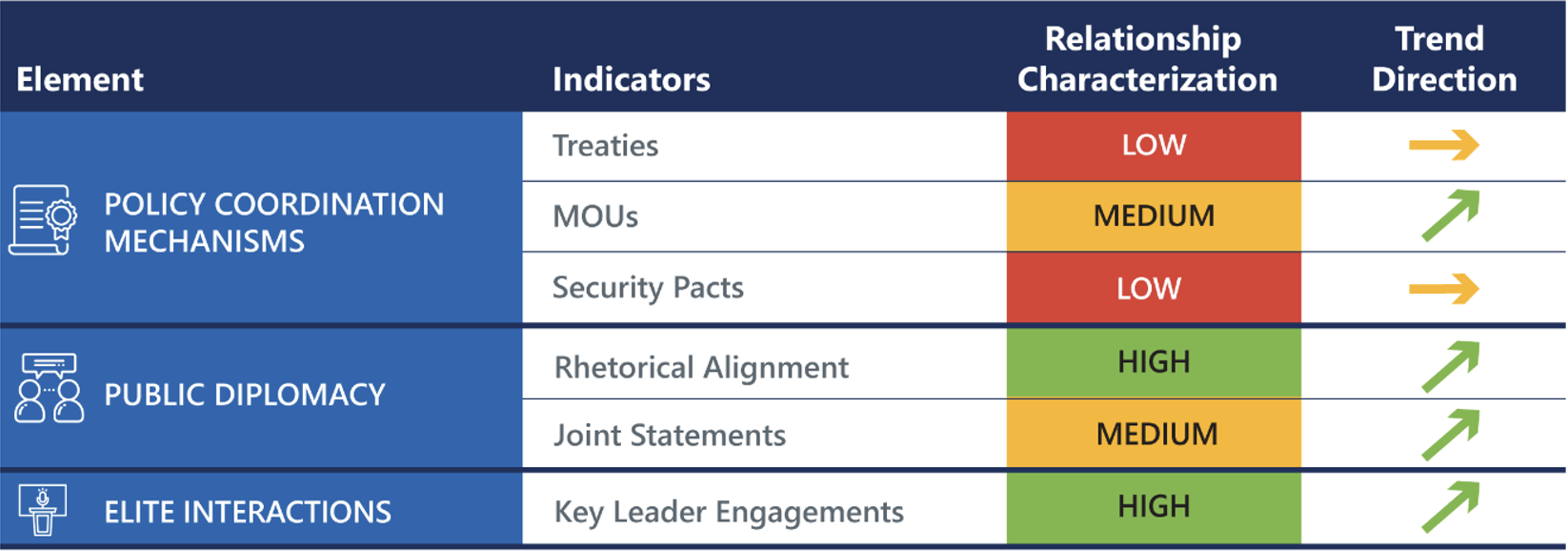

Where there were relatively low ties (such as in formal treaties and security pacts), the pattern has remained. Where there have been productive alignment and engagements (such as in symbolic rhetoric or elite interactions), these continue or have increased.

The political dimension to the relationship, broken down into a series of measurable indicator components. Source: CNA.

Although Russia’s partnership with India lacks the depth seen in its relationships with adversary states such as Iran, North Korea, and China, India has nevertheless consistently refrained from aligning with the counter-Russia global sanctions regime. Even as India has pursued a distinctly multi-vector foreign policy and sought to foster positive ties with the United States, it has nevertheless maintained its cooperation with Russia in a tense and divided global environment.

Importantly, even though Sino-Russian alignment has consistently been raised as a tension point by observers, actual Indian foreign policy under Prime Minister Narendra Modi has been to studiously avoid the issue and take a “wait-and-see” approach to exactly how Russia and China coordinate their own relationship. On Russia’s part, it sees India’s attempts to simultaneously foster a warm relationship with the United States as unfortunate but inevitable, and uses a sovereignty and civilization framework as a reminder that India does not need to make zero-sum calculations and can maintain its relationship with Russia even while doing so. The publicly warm relationship between President Vladimir Putin and Modi has consistently signaled this ability to maintain a clear symbolic friendship even given considerable pressures from Washington and Brussels since 2022.

Russia has three overall political objectives in the foreign policy domain vis-à-vis India: to maintain its existing relationship that has endured since the early Cold War, to ensure that India does not overly align itself with the West, and to encourage India as a major global player — a position that Russia, which views itself as a protector of and advocate for non-Western countries, is seemingly happy to see. India, in turn, sees Russia as a partner with which it intends to conduct an independent foreign policy relationship regardless of Western preferences. Overall, Russia appears to be pleased with its relationship with India.

Although not all elements of the relationship show consistent or substantive improvement, all are at least stable compared to previous baselines. More importantly, the Russian-Indian relationship has long had a high floor — that is, relations have been maintained in a constructive fashion for decades, which means there is less need for major work at improvement. Instead, Russia is grateful that India did not join the anti-Russia sanctions regime and sees economic relations as a major benefit of current international dynamics.

Russia is unlikely to feel the need to develop qualitatively closer relations beyond where they already are but it would like to see the continuation of general trends. For India’s part, it is similarly unlikely to view the relationship as needing a tremendous push. It is already going in useful directions and underlies a longstanding position of mutual understanding between the two countries.

The Military Dimension

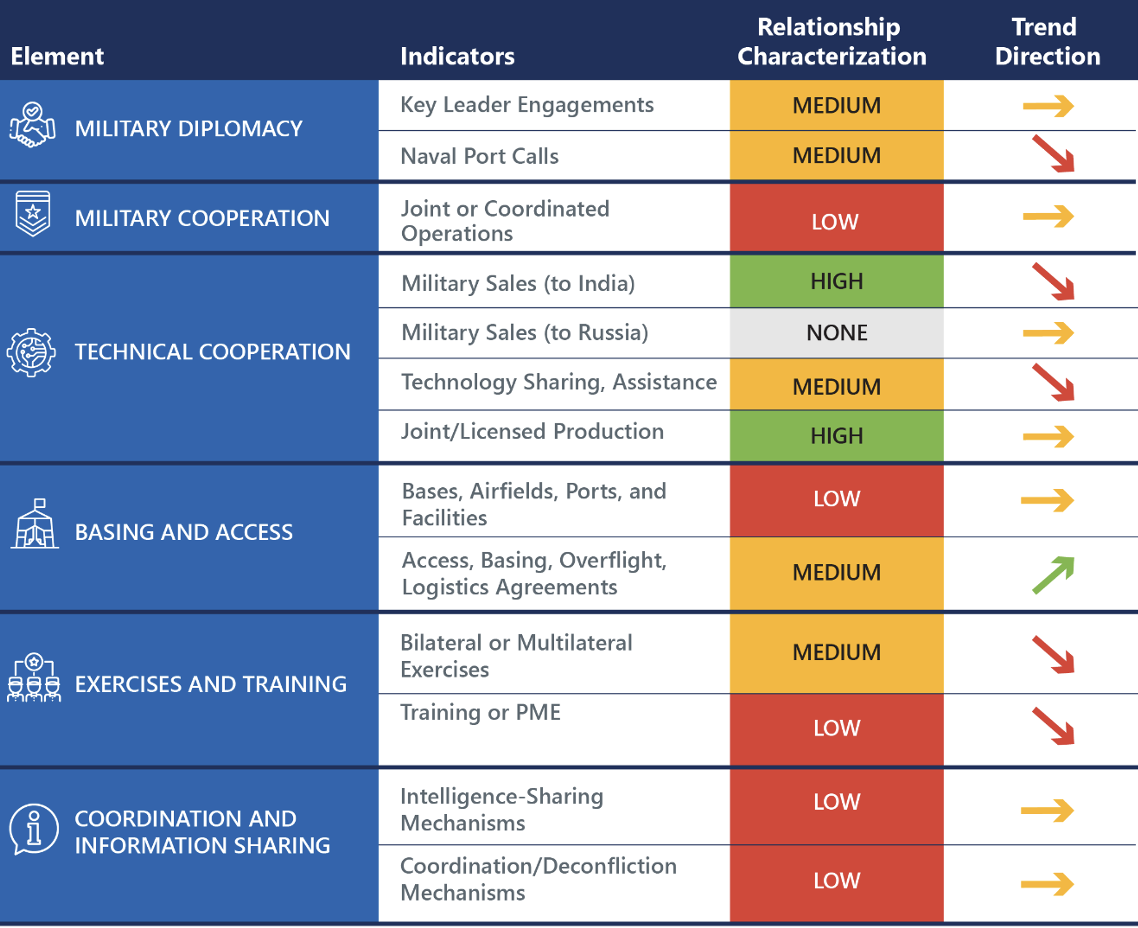

The military relationship between India and Russia is fairly complicated. After a strong period of growth from 2005 to 2019, Russian-Indian military cooperation has largely stagnated over the past five years. After a decade of rapidly expanding cooperation across many spheres, Indian optimism first began to decline in the mid-2010s in response to delays and cost overruns on several procurement projects, such as the Vikramaditya aircraft carrier modernization and the joint development of a fifth-generation combat aircraft. At the same time, India grew concerned about quality problems with already-purchased Russian military platforms and weapons. The subsequent decision to shift to self-reliance in Indian defense production inevitably stalled growth in the strongest pillar of bilateral defense cooperation: military sales. The two countries have historically cooperated at a high level only for arms sales and joint production. That relationship, however, is declining as India shifts to primarily domestic military production and works to diversify the imports it still needs. In a stark illustration of this shift, Russia and India have signed no new arms sales deals since 2021 and no deals for weapons produced under license outside India since 2019.

After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, India canceled or suspended several military purchase agreements with Russia. These included completed deals for 49 new Mi-17 helicopters and the modernization of 85 Su-30MKI fighters. India also suspended negotiations for the purchase of 10 Ka-31 airborne early warning helicopters, 200 Ka-226T light combat helicopters, and 21 MiG-29 and 12 Su-30 fighter aircraft. Several of these cancellations and suspensions were explicitly linked to supply chain and payment problems related to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the subsequent imposition of sanctions on Russia, whereas others were tied to the transition to domestic military production. The only major Indian purchase of Russian weapons currently under negotiation is the potential acquisition of Voronezh-DM long-range radar systems, which was discussed during the December 2024 Indian defense minister visit to Russia.

Meanwhile, joint production remains stable, and India is happy to continue to produce Russian-designed weapons in India under license. Technology sharing is also stable, although there has been a pattern of building great expectations through agreements and joint statements at bilateral leader meetings, then trying again sometime later after nothing develops.

Progress on other fronts, such as joint exercises and military diplomacy, was initially halted by COVID-19 pandemic restrictions. The frequency and sophistication of exercises declined, and direct meetings between officials were suspended. As the pandemic waned, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine led to new limits on interaction. This was partly because the Russian military faced strains and could not devote resources to exercises and other joint interactions, but mostly because Indian leaders limited their interactions after Russia gained pariah status in the international community. The resumption of high-level visits — including by India’s defense minister to Russia in December 2024 — and the signing of new agreements at these meetings suggest that Russia’s isolation is decreasing.

The military dimension to the relationship. Source: CNA.

Military-technical cooperation is likely to continue to decline for two reasons: India is pursuing domestic production, and Russia is limiting exports because it is focused on production for the war in Ukraine (and will likely focus on domestic military reconstitution in the future). Joint design projects, seen as an area of high potential a decade ago, are largely in the past now, with each side going its own way on new designs of missiles and aircraft. As India shifts to domestic production, it is becoming less dependent on Russian technology sharing and training. What remains is a focus on the continuation of licensed production in India of various Russian-designed weapons and platforms, such as T-90 tanks, Talwar-class frigates, Su-30MKI aircraft, and AK-203 assault rifles.

Various efforts to expand military exercises — much touted in the 2010s — have largely stagnated over the past five years. Meanwhile, there has been little to no discussion of advances in coordination and information sharing. The only indicator that is increasing is logistics and base access as the result of a new agreement signed in February 2025, but this increase is from a low baseline.

Overall, given the decline of defense-industrial cooperation, the previous trajectory of growth in the military relationship is unlikely to resume. The likeliest trend is a steady state, with little growth but no significant decline. Over time, joint activities may play a more significant role than defense-industrial cooperation, but this shift would take time to develop.

The Economic Dimension

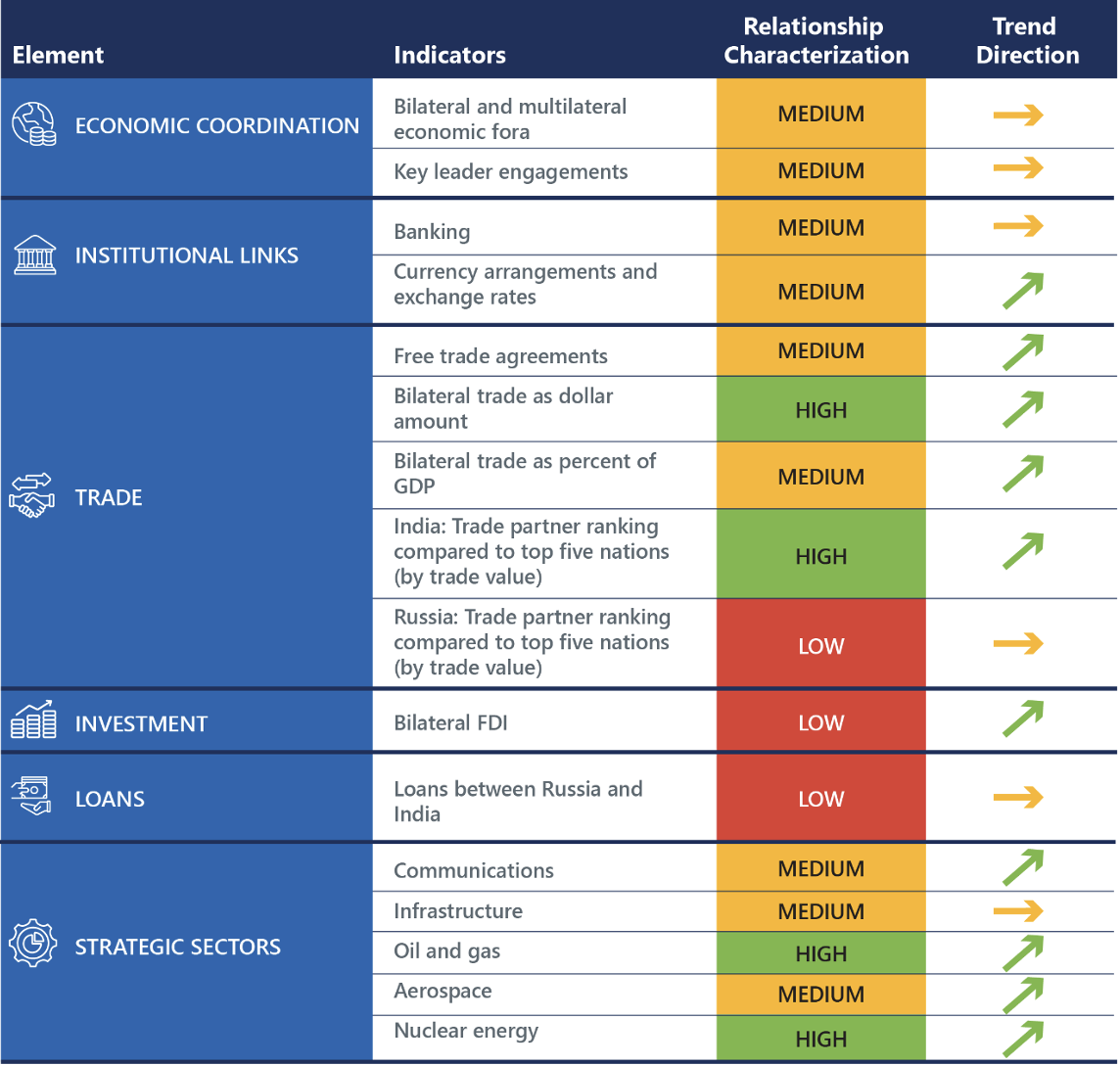

The bilateral relationship has improved the most in the economic sphere. Russian-Indian economic cooperation is booming in terms of bilateral trade and their combined efforts to ease financial transactions with one another. India and Russia have one of the fastest growing trade relationships in the world, driven by India’s sharp rise in fossil fuel consumption. As a result, total trade between Russia and India grew more than 30 percent in the past year.

The economic dimension to the relationship. Source: CNA.

Russia has reoriented away from the West and needs new markets for its petroleum products, so it has been happy to sell to India even at a discount. However, oil, gas, and coal are not the only features of the trade relationship. The two countries have significantly diversified their trade portfolios to goods such as fertilizers, seed oils, and medicines — and this diversification will continue as investments in other sectors gather momentum. There have also been renewed efforts to cooperate in key sectors, including aerospace and information technology. These areas of the economy are notoriously sensitive, given their defense applications, and cooperation in these sectors signals an underlying willingness to work together.

These trends, driven largely by the war in Ukraine and India’s high energy demands, will likely continue. As trade grows between the countries, they are seeking financial integration outside the U.S. dollar payment structure. Both countries are looking for ways to address convertibility issues, reduce their reliance on the U.S. dollar, and work around sanctions (Russia) and capital controls (India). This shared interest has resulted in the introduction of mechanisms such as vostro accounts that allow for international transactions without the use of an intermediary currency such as the dollar.

Barriers to deeper coordination remain in place. Notably, Russia and India remain focused on attracting foreign investment to their own markets, they do not rank highly as sources of outside capital for each other. Deeper financial integration will be a key determinant of how much further the bilateral relationship can go. The trade imbalance is another source of concern, and geopolitical loyalties remain misaligned. India leans toward the West in economic relations, as the United States and Europe remain more important partners than Russia. It is also wary of secondary sanctions and cautious about deeper involvement in groups like BRICS and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, which it sees as dominated by China.

Notwithstanding those barriers, both countries’ leaders have expressed the political will to overcome regulatory hurdles and foster more investment. The free trade and investment deals reportedly nearing completion should help facilitate this process. So, too, will the infrastructure projects sponsored by the BRICS New Development Bank.

Of course, those infrastructure projects are expensive and will take considerable time to build, as illustrated by the International North-South Transport Corridor. Therefore, it will be years before robust infrastructure can reduce the logistical issues both countries are facing. But breaking ground on these projects, including nuclear power plants in India with Russian technology and co-funding, demonstrates a forward-looking approach.

Implications

The Russo-Indian relationship is stable, but not nearly as close as Russia’s relationships with key partners such as China or Iran. Russian leaders are eager to maintain a strong relationship, considering that India plays an important role as a trendsetter for other states in the Global South. India likewise sees the relationship with Russia as visible proof of its commitment to a multipolar global order.

India recognizes the importance of its relationship with the United States, but it does not view that connection as requiring the abandonment of other key foreign ties — certainly not with another great power like Russia. While New Delhi values strong relations with Washington, it does not regard Moscow as an adversary and sees no contradiction in pursuing positive ties with both. For U.S. policymakers, coming to terms with this capacity to hold “two thoughts at the same time” is essential to understanding the dynamics of the U.S.-Indian-Russian triangle.

Any U.S. strategies attempting to break Russia and India apart would have to focus on substantive reasons for India to turn away based on material interests. Moralizing or emphasizing Russia’s pariah status is unlikely to be compelling to current Indian elites. Although positive interpersonal relations between Putin and Modi help to drive the relationship, a leadership change would be unlikely to significantly shift its overall trajectory, given the structural drivers of the relationship and its positive history. In fact, letting the relationship float free without undue interference may introduce useful frictions with China over the medium to long term.

India is fundamentally pragmatic in its military ties with Russia. Although it has canceled potential arms deals with Russia since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, it did not do so to punish Russia for its actions. Instead, the cancellations resulted from concerns about quality and Russia’s ability to meet delivery targets, plus a general desire to build more in India. Military-technical cooperation is likely to continue to decline, and bilateral military exercises will likely remain limited in number and confined to relatively basic activities. As a result, the symbolism of bilateral military relations may become more important than actual concrete achievements.

Finally, U.S. sanctions have undoubtedly helped strengthen Russia’s economic ties with India, even as Indian firms have limited their trade with Russia because of the threat of secondary sanctions on countries and companies doing business with Russia. Further deepening of Russian-Indian trade ties will likely hinge on the completion of current trade deal negotiations, in which India is attempting to secure more favorable terms for its exporters. The lack of an investment treaty also remains a barrier because both Russia and India suffer from shortfalls of infrastructure investment.

Current U.S. policy toward India is best served by recognizing a few enduring realities. The civilizational framing of multipolar politics remains a comfortable fit for both Moscow and New Delhi, and military ties between Russia and India are unlikely to truly challenge American interests in the near term. The continuation of the war in Ukraine has shifted incentives toward economic collaboration, deepening rather than loosening the relationship. And however one judges it, the partnership is not something that outside powers can easily bend to their will. An approach grounded in this understanding can help Washington navigate the complex ecosystem of Eurasian power politics with greater clarity and steadiness.

Dmitry Gorenburg, PhD, is a senior research scientist at CNA, a not-for-profit research and analysis organization. He is editor of the academic journal Problems of Post-Communism and an associate at Harvard University’s Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies. He has written widely on Russian military affairs, Russian foreign policy, and the Russian navy.

Julian G. Waller, PhD, is a research analyst at CNA, and professorial lecturer in Political Science at George Washington University. He has written widely on Russian political-military affairs, authoritarian politics, and illiberal ideologies worldwide.

Jeffrey Edmonds is a senior research scientist at CNA. He previously served as the director for Russia on the National Security Council and acting senior director for Russia during the 2017 presidential transition. He previously served as a senior military analyst with the Central Intelligence Agency, covering Eurasian militaries. He has served in the U.S. Army on both active duty and the reserves for 24 years, with tours in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Jeff Kucik, PhD, is a research scientist at CNA with 17 years of experience analyzing global markets and economic security in government, industry and academia. He is currently a fellow at the Wahba Institute for Strategic Competition and teaches international political economy at the University of Arizona.

Image: Government of India Press Information Bureau