The Challenge of Tripolar Arms Competition: Lessons from the Washington Treaty

This week, the Joseph R. Biden administration met with Chinese representatives for an initial discussion on the future of strategic stability. The administration hopes that this meeting will serve as a first step in a larger dialogue on limiting nuclear arsenals. After years of struggle to engage China on nuclear issues, hopes now run higher that the United States and China might head off their escalating race to modernize and expand their nuclear forces.

American interest in arms control dialogue is understandable. As China and Russia modernize and expand their nuclear forces, the United States faces an increasingly dangerous world marked by two great power competitors. The recent Congressional Commission on the Strategic Posture of the United States highlighted this challenge, writing, “Our nation will soon encounter a fundamentally different global setting than it has ever experienced: we will face a world where two nations possess nuclear arsenals on par with our own.” American leaders naturally hope to curtail this emerging challenge through negotiation. Yet the Congressional Commission predicts that while “the United States will continue to reduce risk with China and Russia when and where possible to enhance U.S. security … it will also need to prepare for a future in the 2027–2035 timeframe when formal arms control treaties are difficult to achieve or absent.”

The commission’s skepticism about arms control’s near-term prospects is well founded, as balancing the competing demands of multiple great powers in a single negotiation is incredibly difficult. One important example of the promises and perils of multilateral arms control is the Washington Naval Treaty, which was ratified 100 years ago in August 1923. The treaty regulated strategic competition between Great Britain, Japan, and the United States in the 1920s and 1930s. It is a hopeful example for future tripolar risk reduction.

Unfortunately, the domestic and international political bases that enabled the Washington Treaty are absent in Chinese-Russian-U.S. relations today. Convinced that they can arm their way to security, Chinese and Russian leaders are simply not interested in serious arms limitation. As American strategists consider the future of competition with China and Russia, the main lesson from the Washington Treaty ought to be the importance of American power in creating the conditions for future arms control success. The congressional commission’s recommendations for strengthening American deterrence, including continuing nuclear modernization, strengthening the industrial base for future competition, and enhancing conventional deterrent forces, are thus also the best possible path toward robust risk reduction in the future.

An Arms Control Breakthrough

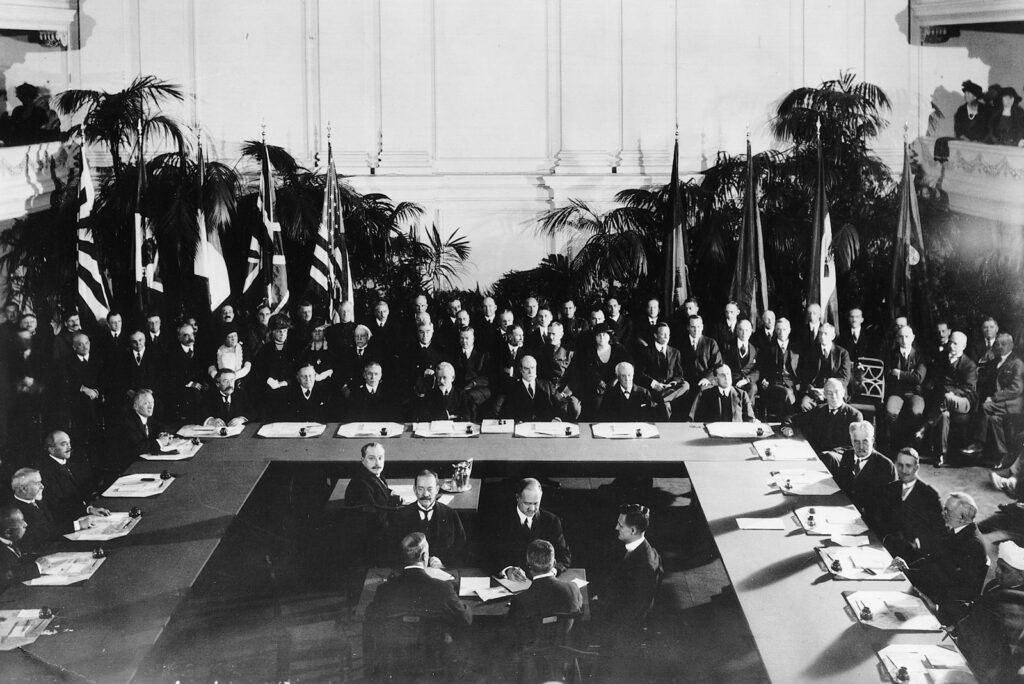

The Washington Naval Treaty resulted from an American diplomatic initiative, an invitation issued in 1921 by President Warren G. Harding to the world’s leading sea powers to attend an international conference in Washington to stop an emerging competition in naval armaments. Harding opened the conference on Nov. 12, 1921, with a short, solemn welcoming address to the delegates from other countries He declared that in the United States, “Our hundred millions frankly want less of armament and none of war.” The president’s remarks received loud applause from the audience.

Harding’s speech was the warmup act. Secretary of State Charles Evan Hughes took center stage in leading the opening session. Instead of another welcoming speech, Hughes stunned the other conference delegates by presenting a detailed arms control proposal. He called for an immediate stop to the competition in capital ships, the most powerful warships of their day — yesterday’s deterrent. His proposal spelled out the names of the ships whose construction would be stopped and of older battleships to be scrapped. The secretary of state demanded: “Preparation for offensive naval war will stop now.”

America’s opening diplomatic salvo took the delegates by surprise and gave Hughes the initiative in negotiations. Arthur Balfour, speaking in response for the British delegation, called the American proposals “bold and statesmanlike.” The American initiative spurred the negotiators to achieve what had seemed impossible: an arms control agreement to curtail naval construction by Britain, Japan, and the United States. Under the terms of the treaty, the three great powers agreed to scrap or cancel 66 capital ships.

Political Roots of Success

While Hughes jumpstarted the negotiations, achieving an arms control agreement still entailed hard bargaining. The powerful head of the Senate foreign relations committee Henry Cabot Lodge, who took part in the planning for the conference, did “not for a moment believe that either Japan or England will accept it [the American proposal].” Although urged to attend the conference in person, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George confided to Frances Stevenson, his confidential secretary and mistress, that he “does not want to go to America — loathes the idea.” He did not see the point in traveling to Washington to attend a conference that would fail.

Although the challenges to multilateral arms control were significant, domestic political imperatives in Britain, Japan, and the United States set the stage for the dramatic turn of events in Washington. In the United States, influential voices emerged against any buildup in the Navy. The progressive maverick Republican Senator William Borah of Idaho led the opposition in Congress. Borah championed a congressional resolution calling on the president to invite Britain and Japan to a conference that “shall be charged with the duty of promptly entering into an understanding or agreement by which the naval expenditures and building programs … shall be substantially reduced.” Borah forced President Harding’s hand, setting the stage for the conference in the first place.

In Britain, too, Lloyd George searched for a way to avoid the costs of naval competition. In 1921, Britain’s gross domestic product slumped by 9.7 percent, a drop in the British economy not matched until 2020. In these hard times, Lloyd George’s government came under immense political pressure to cut spending. The outspoken press barons, the brothers Lord Northcliffe and Lord Rothermere, used their influential newspapers to denounce what they deemed as wasteful warship construction. The American call to negotiate was applauded across the British political spectrum as providing a way to avoid a costly arms race.

Japan’s political and financial leaders also balked at the huge cost of a naval arms race. Prime Minister Takahashi Korekiyo advocated a foreign policy of accommodation with Britain and the United States. “Because of the Washington Conference,” he told the Japanese Diet, “we can reduce military expenditures and have a little surplus for the future.” Takahashi saw cooperation with Britain and the United States as enhancing Japan’s power, prestige, and security, his country acting as a “responsible stakeholder” in upholding the peace in Asia and the Pacific.

The Promises and Pitfalls of American Leadership

Domestic political pressure set the stage for negotiations, but the treaty would not have happened without the leadership exercised by the United States. Harding insisted on a diplomatic plan of action to gain the initiative in the negotiations. A month before the opening of the conference, Harding spoke bluntly in an off-the-record interview with a friendly journalist: “We’ll talk sweetly and patiently to them [the other major naval powers] at first; but if they don’t agree then we’ll say ‘God damn you, if it’s a race, then the United States is going to go to it.’” If Britain and Japan had refused to settle, the president would have regained the initiative in domestic politics to push a naval buildup through Congress.

The prospect that the United States might harness its resources to build the world’s strongest navy gave impetus to British and Japanese leaders to reach agreement to curtail American power. British Chancellor of the Exchequer Austen Chamberlain observed that “there could be little doubt that the United States, with their superior resources, would outstrip us in the race” for naval armaments. Similarly, Admiral Katō Tomosaburō, the head of the Japanese navy, observed, “Even if we should try to compete with the United States, it is a foregone conclusion that we are simply not up to it.” To the leaders of Britain and Japan, accommodating the United States appeared the better course of action.

The mixture of liberal politics and American leadership in the 1920s allowed the creation of the Washington Treaty; their weakening in the 1930s spelled its doom. The economic dislocation of the Great Depression drove Americans to look inward, strengthening the isolationist sentiments expressed by Borah over the pragmatic internationalism espoused by Harding and Hughes. Americans were no longer willing to support the security system they had pioneered.

Japanese imperialists saw America’s growing disconnect as an opportunity. Abandoning the late Admiral Katō’s belief that Japan could not compete in naval construction with the United States, Japan’s naval leaders instead argued that America’s overwhelming economic potential would matter little if American leaders could not summon the political will to build a large navy. Emboldened by perceived American weakness, Japanese militarists rejected accommodation with the United States in their determination to break out from the arms control regime that limited warship construction.

At least initially, the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration confirmed the suspicions of Japanese militarists that the United States would not compete in naval armaments. Even after Japan withdrew from the 1936 London Naval Conference, Roosevelt stuck to a policy of trying to entice Japanese leaders back into negotiation through unilateral American restraint. Japan’s naval construction, however, proved self-defeating, as many Japanese leaders of the 1920s had understood. By the late 1930s, with the outbreak of large-scale wars in Asia and Europe, the Roosevelt administration reversed course and ordered the construction of a massive American fleet, far beyond what Japan could possibly match. Alarmed by this American expansion, Japanese militarists still refused to seek an accommodation with Washington. Instead, Japan’s leaders jumped through the “window of opportunity” afforded by their head start in warship construction to strike the United States before it could eclipse Japanese naval power entirely.

Only 20 years elapsed between the surprise fanfare inaugurating the Washington Conference and the surprise attack by Japan on American and British forces in the Pacific. The battleships regulated by the arms control regime negotiated in Washington became the main targets struck by Japanese aircraft at the war’s beginning.

Lessons for the Present

In our own times, the immediate prospects for arms control are dim. The United States is now involved in a three-way nuclear competition with China and Russia. Russia’s takeover of Crimea and invasion of Ukraine stand in the way of any meaningful agreement to limit nuclear arms. New START is on its last legs, as Russia refuses to allow U.S. inspections of its nuclear facilities, while Russian diplomats dodge meetings with their American counterparts. Until the fighting in Ukraine ends, a major arms control agreement with the Russian government is outside the realm of practical politics.

Meanwhile, China is dramatically expanding its nuclear forces, especially its intercontinental ballistic missile and submarine-launched ballistic missile capabilities. The lack of transparency on Chinese decisions about nuclear weapons resembles Japan’s attempts to conceal its capital ship construction during the late 1930s and the Soviet intercontinental ballistic missile buildup that confounded Defense Secretary Robert McNamara’s Pentagon during the 1960s. The growing intercontinental ballistic missile force will provide Chinese nuclear planners with an enhanced capability to execute first strikes in wartime.

There is no force of public opinion within China to constrain this nuclear buildup. No free press exists to spur open debate about the strategic wisdom or necessity of surging toward nuclear parity with the United States. At Washington, 100 years ago, a common liberal world view generated domestic political pressure on the American, British, and Japanese governments to go to the negotiating table. While liberal domestic political pressure exists today in the United States to reduce arms spending, no comparable internal pressure pushes China’s authoritarian regime to negotiate.

This is especially tragic, as China’s rapid nuclear expansion is unlikely to be any more effective than Japan’s race to build predominant naval power was. China today enjoys far greater economic and technological power than Imperial Japan ever did. Yet China’s security situation is also more precarious, surrounded as it is by other economically and technologically capable neighbors, neighbors who will not remain idle while China seeks to overturn the nuclear and military balance. Chinese nuclear expansion will also antagonize the United States, with dire implications for Chinese security. The recent Congressional Strategic Posture Report is the shadow of things to come: more American nuclear weapons, more American missiles, more American forces in Asia. Chinese communist leaders could use an Admiral Katō of their own, to remind them that even their prodigious capabilities are finite. Instead, leader Xi Jinping continues to purge senior military and diplomatic figures in search of ever-greater deference to his dictates.

Hence, Washington’s repeated efforts to engage China in substantive arms control talks have failed. When Harding pitched a conference in Washington to discuss arms control, the British and Japanese governments jumped at the invitation. The Biden administration, like its predecessors, wants to “pursue arms control to reduce the dangers from China’s modern and growing nuclear arsenal.” Reflecting on the recent talks with China, a senior Biden administration official said, “We need to have a discussion with them to better understand their point of view … and hopefully that could lead to a discussion on practical steps that we could take to manage strategic risk, including further down the road, conversation on mutual restraint in terms of behavior or even capabilities.”

Beijing will almost certainly rebuff Washington’s entreaties. China aims for near-parity in nuclear weapons with the United States. If Beijing remains true to that aim, nuclear arms control has no prospect of achieving real limits on Chinese forces before China’s nuclear arsenal pulls even with the United States. Absent the common desire to avoid an arms race that animated the great powers at the Washington Conference, the Biden administration is unlikely to be able to repeat Harding’s dramatic breakthrough diplomacy.

The dangerous decade of the 1930s and the breakdown of arms control provide a much better fit for understanding the strategic predicament that the United States finds itself in today than the period leading up to the Washington Conference. The domestic political conditions of the great powers that produced agreement in Washington a hundred years ago do not hold today. Until China’s rulers are convinced that expanding their nuclear forces does not confer strategic advantage and the contest over Ukraine is resolved, meaningful arms control stands little chance.

Though the short-term prospects are grim, the Washington Treaty can confer one lesson for arms control’s long-term viability: Historically, major breakthroughs in arms control have depended on rivals’ apprehension of American power. British and Japanese leaders responded to Harding’s proposal in part because they recognized the potential consequences of failing to meet on America’s terms. Chinese and Russian leaders do not seem to feel such urgency today. American leaders should heed the advice of the Strategic Posture Commission and get serious about meeting the military challenges posed by great power rivals. This means recapitalizing America’s nuclear forces and enhancing conventional, space, AI, and cyber capabilities to deter war. Indeed, such recapitalization holds the best possibility for future arms control success.

John D. Maurer serves on the faculty of the School of Advanced Air and Space Studies at Air University in Montgomery, Alabama, and is a nonresident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. He is the author of Competitive Arms Control: Nixon, Kissinger, and SALT, 1969–1972, published by the Yale University Press.

John H. Maurer serves as the Alfred Thayer Mahan distinguished professor of sea power and grand strategy at the Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island. He is the editor of two books that examine naval arms control between the world wars. The views expressed in this article represent those of the authors alone.

Image: Wikimedia Commons