The Islamic State is Cautiously Optimistic about a New Turkish Operation in Syria

In internet forums over the past several weeks, Islamic State members have expressed cautious optimism about the benefits of a potential Turkish military operation in northeastern Syria. For the group’s scattered fighters, further Turkish attacks against the Syrian Democratic Forces could represent a unique opportunity to reconstitute their strength. Given the organization’s weakened (yet resilient) state, their optimism may well be misplaced. Still, it would be better for the world not to find out.

Since late November, Ankara’s Operation Claw-Sword has been targeting Syria’s Kurdish forces with long-range missile and rocket strikes directed at bases and installations in Syria. Ankara has also repeatedly threatened a full-scale ground incursion, which Syrian Kurdish leaders have said would prevent them from continuing operations against the Islamic State. As Ankara continues to push back against U.S. and Russian opposition to its plans, U.S. policymakers should do all they can to ensure Islamic State forces don’t get the opportunity they’re hoping for.

Pressure and Opportunity

While Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan continues to brand the Syrian Democratic Forces a terrorist threat, they remain the primary bulwark against the Islamic State in Syria and a key enabler for the Global Coalition to Defeat the Islamic State. Claw-Sword has already degraded, and continues to degrade, the Syrian Democratic Forces’ infrastructure and capabilities — even bases that are shared with U.S. forces have been struck. Shortly after Ankara initiated the operation, the group stated publicly that it would not be able to maintain pressure on the Islamic State’s latent networks if it had to simultaneously withstand Turkish attacks. And the group’s senior officials have expressed their concern at the apparent lack of support from Global Coalition states in the face of the Turkish campaign.

On Dec. 2, Syrian Kurdish forces declared a freeze on counter-Islamic State operations in northeastern Syria, including a suspension of all joint patrols, training activities, and special operations. While the moratorium was lifted later that same day, the incident speaks to the fragility of the situation and underscores the fact that, should Turkey at some point launch a new ground incursion into Syria, Kurdish fighters will not hesitate to reprioritize their resources and capabilities to defend themselves, even if that undermines wider Global Coalition counter-terrorism efforts.

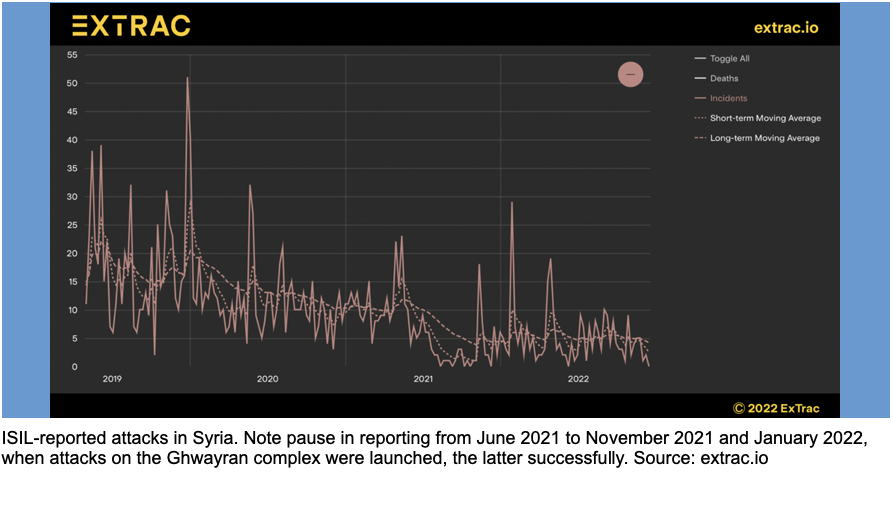

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Islamic State supporters in the region consider the degradation of the Syrian Democratic Forces to be a potentially transformative opportunity. Even the Islamic State’s own official reporting suggests its prospects in Syria have not looked all that good in recent months. The chart above shows the group reportedly conducting less than half as many operations across Syria each month in 2022 when compared with the first six months of 2021.While the Islamic State has been known to under-claim attacks, especially in the Syrian theater, its official reporting nonetheless represents an important reflection of its own perceived strength. On that basis, anything that could spell a change in trajectory for the latent “caliphate” in Syria is bound to create a stir among its members.

While the Islamic State leadership itself has not yet commented specifically on the matter — in part because they are still navigating the killing of their leader Abul Hasan al-Hashimi al-Qurashi — Syria-based Islamic State supporters, the so-called munasirin, have been discussing what Operation Claw-Sword might mean for the movement. To date, their responses have been largely optimistic, but also tempered by calls for restraint.

Optimism and Restraint

Within minutes of Turkey’s first airstrike on Nov. 20, Islamic State supporters were heralding its new intervention as a strategic boon for the group’s increasingly embattled network across Syria. To a large extent, their response in the weeks since has been characterized by a sense of optimism, grounded in the idea that the current air campaign is only a preamble to a Turkish ground operation that will, as one munasir puts it, “grind whatever remains of the [Syrian Democratic Forces] into dust.”

According to this reasoning, the collapse of the Syrian Democratic Forces — or even just the redirection of its resources away from counter-Islamic State operations — would permit an intensification of offensive activity. According to one prominent Islamic State military analyst on Telegram this would “end the stage of attrition,” meaning the low-intensity asymmetric warfare that the group is currently in, and “usher in a new period of bone-breaking tamkin.” In the Islamic State’s nomenclature, the word tamkin or “consolidation” refers to late-stage insurgency and territorial control, something we have not seen from the movement in Syria since early 2019.

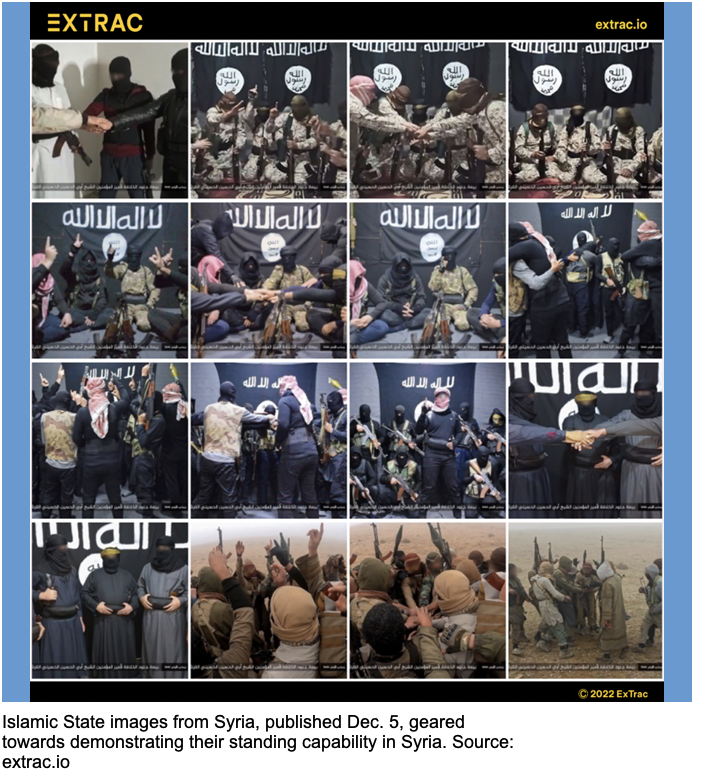

How realistic is this assessment? Recent official communications by the Islamic State’s media apparatus in Syria signal that it retains a substantial and moderately well-equipped network across eastern Homs, Raqqa, Deir Ezzor, and Hasakeh governorates, and potentially beyond. The images below, which emerged in early December, were distributed in part to demonstrate the enduring coherence of the Islamic State in Syria after the death of its leader in Daraa in October. They appeared at what could turn out to be a critical strategic juncture. In the absence of regular operations in the country, the Islamic State’s Media Diwan appears to be trying to signal the fact that it retains a developed standing force there, one that could be operationalized rapidly.

All that being said, the Islamic State response to Claw-Sword also highlights the group’s current weakness and its limited capacity to fully capitalize on the opportunity that new Turkish operation would present. Some within the movement have been actively tempering expectations in closed online discussions, encouraging fellow supporters not to rush into a new campaign without instruction from their leadership. These figures argue that Turkish airstrikes alone would not be enough to make a tangible operational difference on the ground and that talk of a Turkish ground invasion may still be unrealistic.

What’s more, there is no love lost between Ankara and the Islamic State. Their enmity is well-known and deeply entrenched, especially following the Turkish-led Operation Euphrates Shield in 2016 and 2017, which saw the Islamic State ultimately burning several Turkish soldiers alive on film. This means that even if Erdogan were to launch a ground invasion and critically undermine the Syrian Democratic Forces, the residual networks of the “caliphate” would not suddenly find themselves operating in friendly territory.

On that basis, many of these calls for restraint have been aimed at managing the hopes of Islamic State supporters held in Syrian Democratic Forces-run detention facilities in the northeast, as well as the al-Hol, and to a more limited extent Roj, camps. Since 2019, Islamic State leaders have repeatedly stated that their priority in Syria is the liberation of detained supporters in the northeast. Indeed, in every strategic statement since the military defeat of the “caliphate” at Baghuz in March 2019, this has been a core theme.

Yet it was only in January 2022 that the Islamic State’s intent was shown to be anything more than rhetoric. The Ghwayran prison break was a symbolic success but an operational failure. The attack energized the group, but there is still no clear evidence it has had, or will have, a meaningful impact on its capabilities in Syria. Whatever the case, it is certain to have raised expectations that similar efforts will be made to liberate supporters in the northeast’s detention facilities, particularly in the wake of Claw-Sword.

Implications

If Turkey does indeed conduct a new ground incursion into Syria, it has the potential to improve the Islamic State’s operational prospects in both the short and medium term. With greater instability in northeast Syria and the Global Coalition’s key partner distracted, the Islamic State would have more room to project its strength. This would not mean a return to its “golden” years of 2014 through 2016, which saw a sophisticated, effective, and brutal governance across swathes of Syria. Rather, it would mean a markedly more aggressive and ambitious insurgency that is working towards more than just flagging presence and resolve.

Given its successive loss of two “caliphs” in Syria in 2022, the implications of such a resurgence in Islamic State kinetic activity in the country are difficult to predict. With its operations in Iraq at their lowest ebb in over a decade and its media brand now circling more around West and East Africa than anywhere else, the movement’s remnant networks in Syria would have to make quite a splash to wrestle back their past legacy and standing as a core component of the global Islamic State insurgency. Be that as it may, no matter how much better its military prospects are in places like the Lake Chad Basin, Syria, like Iraq, is just too ideologically important for it to give up on.

As of now, there are no indications that operations are being planned to exploit Claw-Sword. Indeed, there are clear attempts to downplay the expectations of supporters, particularly those in detention centres hoping for a “liberation” operation by Islamic State cells. Yet, observers also saw local networks in Syria go quiet in the run-up to the attack on Ghwayran prison. The Islamic State is very unlikely to signal — beyond indirect suggestions of operational intent and capacity — that any new campaign is being prepared. Moreover, the group only recently acknowledged that Abul Hasan al-Hashimi, its last “caliph,” had died in October. This means the timing is “right” for a revenge campaign, as happened in the wake of the deaths of al-Hashimi’s two predecessors.

In the near term, it is critical that U.S. forces and their partners continue to exert pressure on what remains of the Islamic State in Syria. A dead “caliph” is a tactical win but not a strategic victory. Based on Tuesday’s joint air-to-ground missile strike in al-Bab — which, early reports suggested, was targeting a senior Islamic State official from Yemen — it would appear that’s exactly the plan.

But along with that kinetic pressure on the Islamic State, the United States should exert diplomatic pressure on Turkey — to the extent that it is possible — to mitigate the chances of a new ground incursion. If that were to happen and the Syrian Democratic Forces were to wind back its operations, however briefly, U.S. tactics in Syria would almost certainly shift toward short-term, reactive unilateralism rather than strategic interdiction efforts. This is a change that the counter-Islamic State mission can ill afford.

Dr. Charlie Winter is Director of Research at ExTrac, an AI-powered threat intelligence system. Over the last decade he has worked in a range of academic positions in the US and UK, researching how and why insurgents innovate to further their political and military agendas in both on and off-line spaces.

Image: Wikimedia Commons