People Win Wars: A 2022 Reality Check on PLA Enlisted Force and Related Matters

Editor’s Note: One of the authors of this article is protected with a pseudonym. Regular readers of War on the Rocks know that we allow this in only the rarest of cases. Please see our submissions guidelines to read more about how we make these judgments.

Modeled after the Soviet Red Army at its creation from its name to its first flag, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has also long struggled with one of the problems on display in Russia’s war against Ukraine: weaknesses in the enlisted force. The people of the PLA remain the weakest link of China’s defense modernization effort, as we discussed in these pages in 2020, and this may have direct consequences for Chinese Communist Party leaders’ calculations on the use of force — especially their confidence in initiating conflict. Citing Xi Jinping’s key instructions on force building given at a PLA Rocket Force (then-Second Artillery Force) base in 2015, official commentators frequently emphasize the point that “without our grassroots officers and enlisted force, no matter how magnificent the strategy is, it won’t be executed; no matter how advanced the weapon system is, it won’t work.” Those instructions remain operative today.

Xi’s attendance at a Central Military Commission “Talent Work Conference” in late 2021 highlighted that the PLA is engaged in more than just talk. In recent years, the PLA took on a series of ambitious personnel reforms and policy adjustments in the hope of strengthening its enlisted force and boosting its overall readiness level. Have things been going as planned?

Overall, yes. The PLA has made tangible improvements to the readiness of its conscript force in the short term. It has also enacted sensible policies that have the potential to boost quality of new noncommissioned officers (NCOs) and retention rates of experienced NCOs. However, the PLA will not know if this potential payoff will occur until a generation from now.

To understand why this is the case, we provide an updated account of the state of the PLA enlisted force and related force-design matters as of summer 2022. While it may be assessed that the overall readiness level of the PLA has slightly improved now that it brings conscripts on board twice a year instead of once — a change made in 2021 — new challenges have emerged in training as well as in interpersonal relationships between the spring and fall recruits. Corruption in the recruitment process continues to be prevalent. As China’s economic growth stagnates, the Chinese government openly calls on the PLA to create “job opportunities” for college graduates to help alleviate the pressure on the tightening civilian job market. Meanwhile, the PLA continues to adjust its NCO corps, allowing them to serve longer as they assume greater leadership responsibilities and the contingent of non-active-duty civilian personnel continues to be expanded. Yet official assessments of PLA officer and NCO leadership capabilities continue to be lower than expected. As recently as in July 2022, PLA press was referencing a statement made by Xi in late 2015 that reflects his dissatisfaction with the state of the PLA’s human capital:

“What I think most is whether our army can always adhere to the Party’s absolute leadership, whether they can fight victoriously, and whether commanders at all levels can lead troops to fight and command in war when the Party and the people need it.”

Twice a Year, Twice the Problems?

Roughly 700,000 personnel out of the PLA’s 2 million strong active-duty force are conscripts. Although these conscripts are the least trained and capable in the PLA’s human talent pool, they still play a vital role in not only manpower-intensive missions such as ground combat operations, but also in select technical missions. These conscripts serve for two years, so the manner in which the PLA recruits and trains these personnel with a very limited service-period is of the utmost importance.

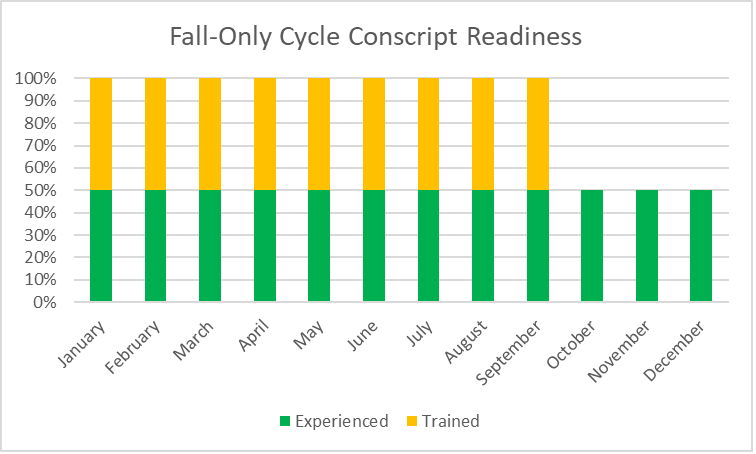

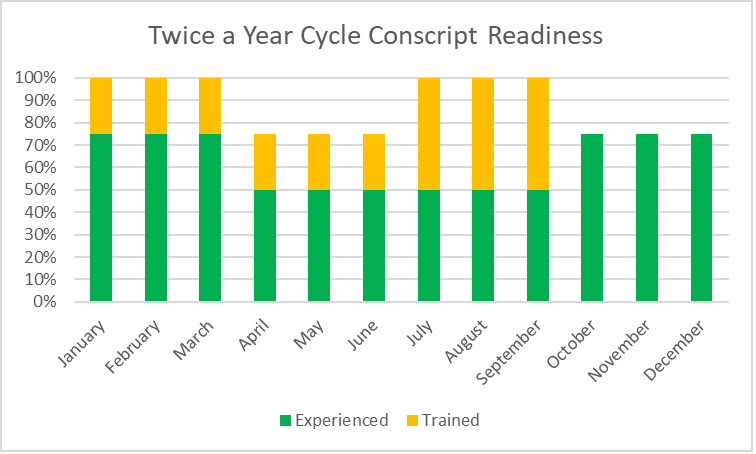

The PLA’s two-year service period for conscripts far exceeds Taiwan’s four-month service requirement and Russia’s 12-month requirement. However, the PLA’s once-a-year conscription cycle resulted in wild swings in terms of personnel readiness. In an effort to remedy this issue, the PLA shifted to a twice-a-year cycle in 2021 by distributing the flow of conscripts into and out of the force across two time periods rather than one. This shift to spring and fall recruitment is designed to improve personnel readiness levels by optimizing training schedules rather than increasing the total force size and results in higher average unit-manning levels year-round. While the overall conscription number remains unchanged, the new practice, according to a staff officer working for the mobilization bureau of Anhui Military District, dictates that the spring recruitment meets 45 percent of the annual quota and fall recruitment takes in the rest of 55 percent of the total annual force.

New PLA conscripts must undergo three months of basic training to become minimally trained and likely are not considered experienced until they take part in the PLA’s annual summer training season. Under the old once-a-year system, roughly 50 percent of the PLA’s conscripted force would qualify as “experienced” across the year. Between October and December, newly recruited conscripts were still undergoing basic training and thus could not contribute towards unit readiness. As such, for those three months, 50 percent of conscripts in the PLA were unable to support even basic combat operations. For the remaining nine months, those conscripts met minimum training requirements and only become experienced as the previous batch of conscripts cycled out of the force.

Under the new twice-a-year system, training schedules ensures that the PLA always has at least 75 percent of its conscripts at a minimally trained level and available.

The PLA seeks to use “precision recruitment (精准征兵)” to fill billets in units with new personnel with the proper education and background. In order to do so, some recruiters in thousands of People’s Armed Forces Departments in townships, commercial enterprises, and schools throughout China have begun to use big data and social media to target specific individuals or their skills. However, there also are reports that “the phenomenon of ‘not being able to use who is recruited, and not being able to receive what is needed’ still exists.” And retaining college students beyond their initial service is a problem because some recruits do not feel their expertise is properly utilized.

The PLA openly acknowledges that the new schedule poses challenges to the existing conscription institutions and the workforce supporting force recruitment is adapting to the new situation. As we noted in 2020, zhuanwu ganbu (专武干部), who are civilian cadres manning People’s Armed Forces Departments, were already notoriously underpaid and overworked prior to the reform. Spring conscription, which takes place around the Chinese New Year, also overlaps with their existing tasks such as militia training and readiness training. Furthering the workload is the expansion of “pre-enlistment training (役前训练)” for new recruits conducted by local People’s Armed Forces Departments before they are shipped off to PLA training bases. During “pre-enlistment training,” new soldiers receive uniforms, learn the basics of drill and ceremony, and undergo political and physical fitness tests, intended to weed out those who might not finish basic training. Despite the moderate expansion of the size of the cadre by assigning a portion of the PLA’s non-active duty, civilian personnel to work in People’s Armed Forces Departments, many, according to PLA Daily, have been thrown into “panic mode (手脚忙乱).”

While the challenges recruiters face were somewhat anticipated, the PLA units on the receiving end appear to be ill-prepared to manage the interpersonal relationships among its “twice-a-year” recruits who now enter service six months apart yet wear the same military rank. For instance, a private who enlisted in fall 2020 and was assigned to an artillery battalion in the 72nd Group Army confessed that he attempted to bully another private in his unit who was a spring 2021 recruit just to demonstrate his “senior” status. Although official PLA accounts seek to depict such topics in a positive light, the fact that such an issue receives official acknowledgement suggests that it is possibly a prevalent issue that warrants high-level attention.

PLA and China’s Youth Problem

While some American analysts believe that the United States is “on the cusp of a recruiting crisis,” China has been taking on sophisticated approaches to address its recruitment and retention problems for years, with mixed results.

It is generally believed that a tightening civilian job market is conducive to military recruitment. However, youth unemployment remains a politically sensitive issue to the Chinese Communist Party. The PLA, by definition, serves as a political tool to safeguard and advance the party’s interest, hence it is likely to be tasked to absorb unemployed workers. China’s National Bureau of Statistics reports that as of June 2022, the estimated youth unemployment rate in urban areas was 19.3 percent compared to 13.5 percent in early 2021. Perhaps in response, in late 2021, China’s Ministry of Education openly called on the PLA to create “job opportunities” for college graduates to help alleviate the pressure on the civilian job market. This makes an interesting contrast to India’s recent military reform known as the “Agnipath Scheme” — recruiting new soldiers for only four years — which fueled violent protests in India’s southern state of Telangana. Chinese news outlets, with or without official affiliations, appear to conclude that youth unemployment concerns and lack of government-provided support may have contributed to such unrest.

The decision to change the conscription cycle from once-a-year to twice-a-year in 2020 (ultimately implemented in 2021 due to COVID-19 lockdowns) was likely based not only on readiness considerations but possibly also on desires to increase the proportion of college graduates recruited into the force. Indeed, various local government and university mobilization websites made it abundantly clear that the spring recruitment was designed to target college graduates. The PLA also intends for the fall induction period to make entering the military more convenient for recent college graduates and students who plan on resuming their studies after their two-year enlistment. In terms of the quality of recruits, Chinese online commentators (with possible PLA affiliations) note that the new approach better accommodates college students’ senior-year schedule to mitigate the adverse effect of “distractions from internship, job hunting, and temporary unemployment.” In 2022, the PLA organized a designated career fair for college student enlistees who completed their two-year conscriptions. Preferential treatment was also given to college-student conscripts who seek to join the PLA’s civilian personnel workforce, which is now managed by a designated bureau nestled within the Central Military Commission’s Political Work Department, separate from the enlisted force management. This effort may also alleviate the aforementioned youth unemployment issues.

Further complicating the issue, in recent years China’s notorious “996 work culture” and increasingly unbearable living cost has given rise to its own version of a counterculture movement — an increasingly larger Chinese youth population embraces the sentiment of “lying flat (躺平)” and “doing nothing” to reject official preaching for self-realization. Despite the lack of official acknowledgement of this issue, it is almost certainly that such a movement and an overall lack of interest in work among relatively better-educated Chinese youth from middle-class families will have direct impact on the PLA’s recruitment numbers.

The NCO Corps: Head of the Soldiers, Tail of the Officers

Professionalization of any NCO corps is not a binary state, but rather a constantly evolving process. While the PLA is quite forthcoming about perceived deficiencies in its own NCO corps, this does not suggest that the PLA does not trust its NCOs. PLA NCOs fill and succeed in a variety of roles across the force, including master chief and sergeant majors at battalion level and above, staff NCOs on battalion and higher staffs, and squad leaders. Sometimes they serve as acting platoon leaders and in that role sometimes lead Chinese Communist Party organizations, i.e. ad hoc “party small group (党小组).”

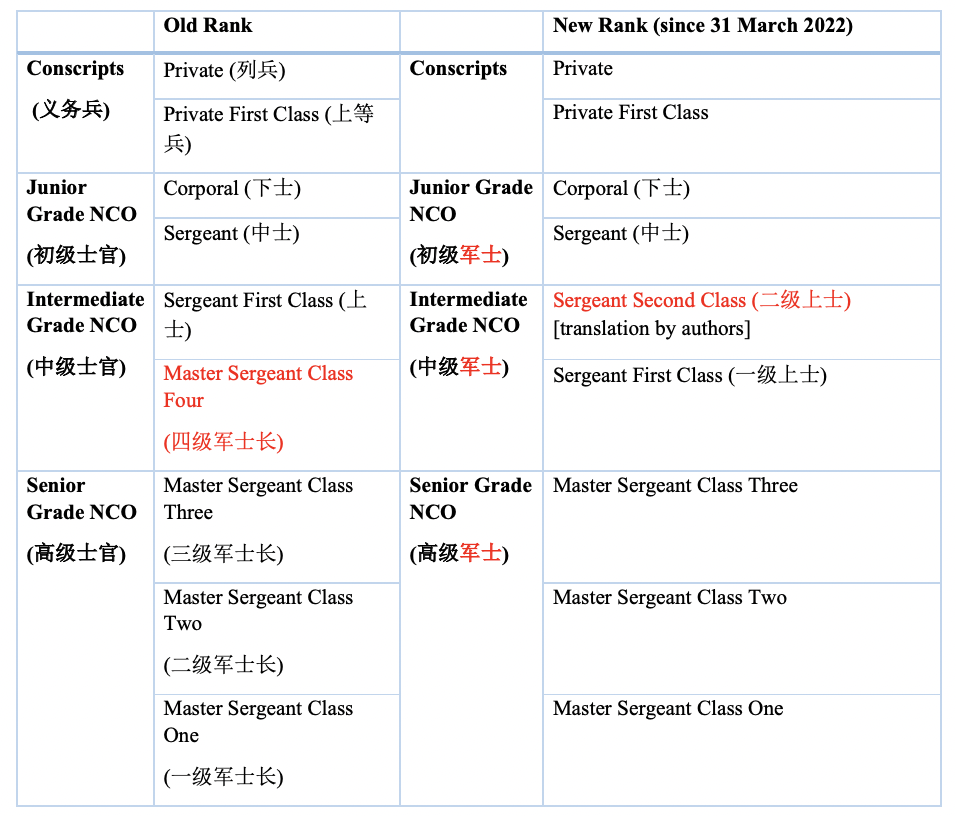

Given the importance that NCOs play in providing leadership and technical expertise, the PLA is continually seeking to improve the way in which it manages this portion of the force. In 2022, the PLA announced a series of changes to its NCO corps. It started with a name change in Chinese. NCOs are no longer called shi guan (士官), or “officer of soldiers,” a Chinese translation used for Western NCO systems, but rather jun shi (军士), a more traditional Chinese term for NCO. The names of the two NCO intermediate ranks also were changed in Chinese (to 一级上士 and 二级上士, presumably sergeant first class and sergeant second class), but no official English translation has been provided. The new names now parallel the form of the three senior NCO ranks (一级军士长, 二级军士长, 三级军士长), translated from highest to lowest as master sergeant class one, two, and three, which have been used since 2009. See table below.

PLA conscripts and NCOs “Three Grades and Seven Ranks (三等七衔),” from lowest to highest in rank.

More importantly, interim regulations for NCOs and enlisted personnel were issued in the spring. Though details have not been spelled out publicly, the new regulations broadly aim to improve the quality of new NCOs, modernize NCO development, and strengthen retention incentives.

For example, the new regulations bifurcate NCOs as “management (管理军士),” those presumably in leadership billets, and “skilled (技能军士),” those in technical positions. They establish a system for certain billets to be filled by certain NCO ranks, and in what numbers, creating a codified path for promotion. To help bring new and better-educated NCOs into the ranks faster, the new regulations also allow qualified conscripts to become an NCO before their two-year service commitment is up. There is also the potential for faster promotions and extending time in rank under the new regulations.

In order to manage the retention of desirable NCO candidates who have not been able to receive promotions or do away with undesirable NCOs, the regulations also establish three types of separation from service. Namely, general separation that meets service requirement (期满退役) based on age or time in rank, controlled separation (调控退役) for intermediate and senior NCOs allowing them to serve longer than four years in one rank, and involuntary separation (强制退役) due to performance issues.

In short, these adjustments likely provide the PLA with greater flexibility to retain and promote higher quality NCOs and do away with those who are less qualified.

Conclusion

The changes to how the PLA manages its enlisted force lead to two noticeable benefits. In the short term, personnel readiness levels, especially in conscript-heavy units like PLA Army combined arms brigades and most marine and airborne units, noticeably improved because of the reforms to the conscription cycle. One potential problem is that this new cycle leaves potential troughs in personnel readiness in late spring, which also happens to be the optimal time of year to conduct amphibious operations in the Taiwan Strait, and late fall. This, however, can be solved by a circumstance-driven extension of service, as has been done in the past at the end of the once-a-year conscription cycle. Furthermore, if the PLA’s efforts to improve its NCO corps management system bear fruit, improvements to the proficiency of its enlisted force will slowly emerge over time.

But such changes also bring short and long-term uncertainties. The revisions to the conscription cycle potentially overloads local military recruitment offices and open the door for more corruption. Potential NCO force-management policies may not pan out, leading to stagnation within the NCO corps. Lastly, long-term economic and social prospects in China could drive the overall quality of new PLA personnel downward by prompting a further loosening standards for induction.

In the next five years leading to the centennial anniversary of the founding of the PLA, the development of military personnel remains a critical benchmark affecting Xi’s key military decisions. Two days before Aug. 1, Xi called on the PLA to “overcome outstanding contradictions and problems restricting the military’s personnel work and for innovation in talent cultivation, including deepening the military academy reform, and innovating military human resource management.” Much remains to be accomplished.

Whether stated explicitly or implicitly, Xi and the senior Chinese military leadership agree that fixing the PLA’s people problems is at the core of increasing the force’s combat readiness and becoming a world-class military. Due in part to social factors beyond their control, the timeline to solve the personnel management challenge is decades or a generation in the future, not years. However, the PLA may not have decades or a generation. There is always the chance that the Chinese Communist Party, possibly reacting to external actors’ behaviors or political messaging, feels the need to use force to reverse perceived threats to national sovereignty or security interests before the PLA fully resolves its personnel management issues. In this case, the PLA will have little choice but to fight with the force it has.

Marcus Clay is an analyst and Roderick Lee is the research director with the U.S. Air Force’s China Aerospace Studies Institute. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Air Force, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

Dennis J. Blasko is a retired U.S. Army lieutenant colonel with 23 years of service as a military intelligence officer and foreign area officer specializing in China. From 1992 to 1996, he was an Army attaché in Beijing and Hong Kong. He has written numerous articles and chapters on the Chinese military, along with the book The Chinese Army Today: Tradition and Transformation for the 21st Century.

Image: China Military