Don’t Call It a Gray Zone: China’s Use-of-Force Spectrum

Editor’s Note: One of the authors of this article is protected with a pseudonym. Regular readers of War on the Rocks know that we allow this in only the rarest of cases. Please see our submissions guidelines to read more about how we make these judgments.

On Oct. 30, 2020, Gen. Mark Milley, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, placed a phone call to assure his Chinese counterpart that the United States did not intend to start a war with China. Both U.S. and Chinese government circles have come to refer to this phone call and the events surrounding it as the “October surprise.” This event shows us, among other things, what happens when there are misperceptions about the use of force on both sides and the potential dangers of said misperceptions. By better understanding China’s philosophy about the use of military force, U.S. policymakers may be able to lower the chances of future surprises happening.

Xi Jinping believes in and likely mandates that the Chinese military use force in accordance with a concept he calls “peacetime employment of military force (和平时期军事力量运用).” In short, this concept guides the People’s Liberation Army to use force to prevent adversaries from reaching China’s “bottom line” in a national-security sense. The Western defense community has explored parts of this concept through studies on what the West calls China’s “gray zone operations,” though China does not have a “gray zone” military strategy. Western analysts have also explored what happens when this use-of-force concept fails, and China is forced to reconstitute its “bottom line,” through discourse on how to defeat a Chinese invasion of Taiwan. However, neither of these fields of study address the People’s Liberation Army’s “peacetime employment of military force” concept as a whole. Consequently, U.S. planners and policymakers are not only working on an incomplete theory on how China uses force, but are also failing to address a swath of potential military options that China might undertake.

Use War to Stop a Larger War

In 2016, official People’s Liberation Army media described “peacetime employment of force,” along with “holistic management and planning of war operations,” as Xi’s new national security concepts. This critical piece of Xi’s military thought is an “expansion and deepening” of China’s long-held active defense strategy. While noting that the concept is a necessity to sustain China’s growing comprehensive national power, the People’s Liberation Army describes its purpose as to “manage and control crises” and “prevent war” in the face of “intensifying tensions in [China’s] neighborhood.” Similar to the U.S. conflict continuum, it explicitly stated that “low intensity use of force in peacetime” is between “peacetime no use of force” and “wartime wholesale use of force.” “Peacetime use of military force” is a manifestation of “bottom-line thinking (底线思维),” which the People’s Liberation Army defines as using military power to warn “relevant parties not to cross [China’s] redlines.”

Xi’s belief in “using force to prevent war” featured prominently in his speech to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the Korean War in October 2020. When compared with a similar public speech delivered a decade ago to commemorate the war’s 60th anniversary, Xi appears more confident and assertive, touting the accomplishment of his signature military reform before declaring that “Chinese people understand it fully that [China] must use the languages that invaders understand to communicate with them. It is to use war to stop war, to use force to prevent conflict/war (以武止戈), and to use [war] victory to win peace and earn respect.”

Nevertheless, we should understand the context in which Xi’s 2020 speech was crafted. We now know that Xi and his military leaders were under enormous psychological stress because they were (mistakenly) convinced that China was facing an imminent attack from the United States under the Trump administration. Although there is no public narrative about what instigated China’s concern about a potential war, the combination of President Donald Trump’s unusually China-focused speech on Sept. 22, the occurrence of America’s large-scale “Valiant Shield” Indo-Pacific military exercise in mid-September, and potentially the announcement of U.S. Ambassador to China Terry Brandstad’s early departure on Sept. 14 may have conveyed a bleak picture to China. On Oct. 30, merely a week after Xi’s speech publicly aired, the phone call between Milley and his counterpart took place. Xi’s high-profile speech was possibly delivered to communicate his intent to de-escalate, rather than escalate, an imminent breakout of war.

“Peacetime employment of force” is conditioned by China’s (mis)perception of its own security environment, which is largely shaped by America’s military presence, actions, and rhetoric. Xi’s “assertiveness” should be understood in the context of his predecessors Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao. Even the origin of his “new security concept” can be traced back to an American doctrinal concept.

After years of study and assessment on the rise and fall of U.S. doctrine on military operations other than war, such as FM100-5, 1993, JP 3-07, 1995, and JP3-0, 2006, Hu endorsed the Chinese version of this doctrine, called “non-war military activities,” at an enlarged meeting of the Central Military Commission in 2008, and the concept was addressed in that year’s defense white paper. In 2009, the late Gen. Xu Caihou, then vice chairman of the Central Military Commission, touted China’s commitment to this concept at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington D.C.

Almost parallel to the debate within the U.S. defense community that led to the eventual removal of military operations other than war from the U.S. Joint Publications in 2006, Chinese military thinkers did not unanimously agree with the definition and utility of the concept. There was a consensus regarding the adoption of “non-war military activities” to improve China’s capability to respond to nontraditional security challenges in the 2010s, but there were subtle concerns that placing too much emphasis on the “non-war” aspect of military operations risks “demilitarizing the military.” In 2009, researchers from the World Military Research Department of the Academy of Military Science, the People’s Liberation Army’s top braintrust, highlighted the need for the army to engage in “non war military activities” not just to cope with domestic stability issues, but also to shape an external strategic condition to be conducive to China’s strategic objectives. In his 2009 book, Xiao Tianliang, a deputy commandant of the People’s Liberation Army’s National Defense University, noted that military operations other than war is a useful concept for improving operational and tactical skills, yet suggested that China should think more strategically about how to “employ” military force for “non-war purposes” in peacetime. Xiao reportedly lectured the Politburo of the Chinese Communist Party in 2014, and was promoted to lieutenant general in 2016. Gen. Liu Yuejun (then a lieutenant general commanding the Lanzhou Military Region), in his long 2013 article in China Military Science, similarly argued that “confrontational military activities” are critical when considering “peacetime use of force,” and that the People’s Liberation Army must “use force resolutely and use it preemptively” to defend the core interests of sovereignty and territorial integrity.

Building Out China’s Use-of-Force Spectrum

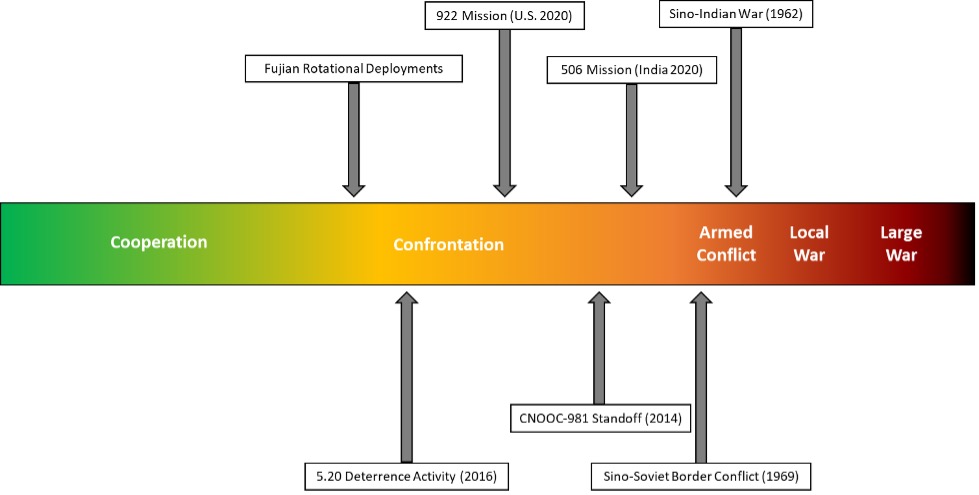

Liu’s article, among other Chinese publications, implicitly talks about the “peacetime employment of military force” occurring along a spectrum, but the People’s Liberation Army does not advertise an equivalent to America’s conflict continuum as featured in JP 3-0. However, a rough equivalent built from Chinese military literature reveals that it looks nearly the same in terms of both intensity and logic.

Liu states that under the guise of “peacetime confrontational military operations,” activities can escalate into a state of military friction, military confrontation, armed conflict, and then local war. These forms of peacetime confrontational military operations are limited in scale and scope compared to “large scale wars.” This forms the basis of reconstructing China’s use-of-force spectrum, although it lacks the specificity or context needed to be useful. But by looking at how other People’s Liberation Army sources describe specific events, one can piece together what these different military confrontational activities involve in terms of scale and intensity.

Figure 1: China’s Use-of-Force Spectrum. (Image by the authors)

One of the inherent problems with using Chinese military theory texts alone is that most of these texts are academic in nature. No known China Military Science or China Academy of Military Science publication defines what makes an event a “military confrontation” as opposed to an “armed conflict.” Examples of “military confrontations” found in texts indicate that this is when two states consistently posture military forces against each other to include the potential for an extremely limited use of violence. Historical examples provided by newspapers and journals characterize the contemporary situation between China and Taiwan, India, and Japan as states of “military confrontation.”

People’s Liberation Army texts also allude to the fact that “military confrontations” may include brief spats of violence. Issue 152 of China Military Science cites the sporadic military clashes between Japan and China in the late 19th century, such as Japan’s invasion of Taiwan in 1874, as military confrontations.

At a certain point, seemingly based on intensity and scale, a situation may evolve into an “armed conflict.” The People’s Liberation Army’s Military Dictionary defines “armed conflict” as a small-scale and low-intensity engagement between two forces that is a transitionary state into “wartime.” Issue 151 of China Military Science describes the 1962 Sino-Indian War as an “armed conflict” and the Dec. 30, 2020 issue of China’s Air Force News cites the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War as an “armed conflict.” Both conflicts lasted roughly a month and involved thousands of combat deaths.

Xi’s Use of the Spectrum Thus Far

Although the People’s Liberation Army has historically been involved in activities falling into the “armed conflict” portion of the spectrum, as of mid-2022 its activities under Xi have not yet spilled into this realm. By mapping Chinese military actions since Xi’s rise to power in late 2012, we can at least see what portions of the spectrum Xi has used thus far.

Baseline Military Deployments: Fujian Rotational Deployments

The People’s Liberation Army’s rotational deployments in Fujian represent a baseline presence to remind adversaries that military force is always an option in achieving political objectives. Starting in 1959 after the Second Taiwan Strait Crisis, the People’s Liberation Army Air Force began rotating units through Fujian to combat perceived Nationalist Chinese airspace incursions around the Taiwan Strait. The military designated such rotations as “Fujian-Based Rotational Combat (驻闽轮战)” and early rotations saw confrontations with Nationalist aircraft. Over half a century later, the air force continues to maintain pressure on Taiwan by rotating units into Fujian under the same “Rotational Combat” nomenclature, although units no longer attempt to shoot down Taiwan’s military aircraft like their predecessors did.

Non-Standard Military Training: 5.20 Deterrence Activity

In May 2016, the People’s Liberation Army conducted a series of non-standard amphibious training events in Fujian province. Internally, the army refers to this series of events as the “Fujian 5.20 Deterrence Activity,” suggesting that it intended the training to deter Taiwan from doing anything escalatory around the first inauguration of Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen on May 20, 2016. The “5.20 Deterrence Activity” represents an escalation from “baseline military rotations” in that it was a deliberate message relayed in response to a potentially troublesome event.

Nationwide Readiness and Disposition Adjustment: 922 Special Mission in Late 2020

The next step in the spectrum is nationwide military activities that aim to explicitly stop adversaries from engaging in escalatory activities. An example of this is the elevated readiness levels that occurred under the “922 Special Mission” in late 2020. Although the “922 Special Mission” appears to have started as early as 2019, People’s Liberation Army units across China engaged in non-standard deployments, heightened combat readiness, or border defense missions from September 2020 into 2021. Furthermore, militia units maintained elevated readiness levels through mid-2021 under this mission. Viewed in light of the later October call between Milley and his counterpart, it seems likely that the People’s Liberation Army intended this elevated readiness to signal to the United States that China believed that the United States was considering the use of force against it.

Non-Lethal Military Confrontation: Hai Yang Shi You 981 Standoff

China’s deployment of the Hai Yang Shi You 981 oil rig to disputed waters in the South China Sea in the summer of 2014 likely represents a low-end military confrontation. Internally, Chinese officials refer to this event as the “Zhongjiannan Security Operation.” Although this activity did not involve the demonstrative use of high-end weapon systems or the use of lethal force, Chinese and Vietnamese forces came to blows through numerous ramming incidents.

Lethal Military Confrontation: June 2020 India-China Standoff

China’s border standoff with India in the summer of 2020 represents the high-water mark of Xi’s use-of-force spectrum as of mid-2022. The People’s Liberation Army has carried out what it calls the “506 Special Mission,” involving rotational deployments of forces to the Sino-Indian Border, since the 2013 Depsang standoff. In fact, the nomenclature of “506 Special Mission” is likely a reference to May 6, the day after China and India resolved the 2013 standoff. However, the 506 Mission escalated in June 2020 when Chinese and Indian soldiers clashed in a contested part of the Himalayas, with lethal results. Based on the limited number of deaths and lack of sustained combat operations, we judge this to be a higher-intensity military confrontation than the Hai Yang Shi You 981 Standoff.

People’s Liberation Army activities under Xi remain beneath their threshold of “armed conflict,” although the military is not clear on where exactly that threshold lies. However, China’s skirmish with the Soviet Union in 1969 might be close to that line. A 2013 article in the People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force’s newspaper discussing “strategic deterrence” identifies the skirmish as a “real combat deterrence activities” rather than a full-on armed conflict.

Figure 2: Xi’s use of force thus far compared to historical People’s Liberation Army events. (Image by the authors)

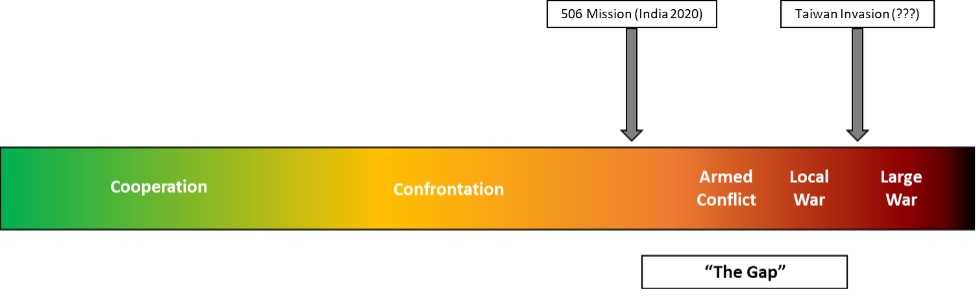

How to Close the Gap

Finding solutions to future land reclamations or island invasions is comparatively easy. Since 2014, the United States national security community has developed a body of research exploring China’s coercive military approach short of war and how the United States can combat that approach. For example, a 2017 Center for Strategic and International Studies report explores ways of countering maritime coercion in Asia to include Chinese military harassment in the maritime domain. There is an even larger library of work advising how to defeat a full-on invasion of Taiwan. Notably, recent experiences from the war in Ukraine provide lessons for how Taiwan might defend itself and how the United States can help. However, there is less discussion about the gap between those two points on the spectrum, despite China’s explicit willingness to “use war to stop war” in that space. We have three recommendations to address the gap.

Figure 3: What Western military analysis is missing. (Image by the authors)

The first recommendation is to consider the full range of potential activities that fall between those two points on the spectrum, and how the United States should respond from a counter-coercion policy perspective, and what the U.S. military’s role is in said response. What if China conducts punitive strikes against Taiwan with the intent to deter further murmurs of independence rather than force Taiwan to capitulate, or rapidly seizes a Filipino outpost in the South China Sea to demonstrate that the United States cannot come to the aid of its allies in time? These potential “peacetime military confrontations” pose unexplored policy and military planning challenges that the United States should resolve.

Second, and more importantly, the U.S. national security community should shift some of its attention towards developing strategic cultural empathy. Often, the United States unknowingly wanders into escalatory situations and subsequently wonders why China responded in the way that they did. The United States can fix this problem by better educating the national security community about issues to which China is sensitive, how China receives strategic messaging, and what China fundamentally values. By internalizing this understanding and acting with deliberate intent, the United States can avoid inadvertent escalation in the future or more effectively deter China.

Finally, as a specific step to strengthen cultural empathy, the China-watching community should conduct more tracing of how, not just what, the People’s Liberation Army learns from Western concepts and doctrine when possible. Such an academic effort would help to bring Chinese military writings into perspective so that poorly defined concepts such as “gray zone strategy” will have little room to proliferate and exacerbate misconstrued Western views about how China evaluates and implements its military strategy.

Roderick Lee is the research director and Marcus Clay an analyst with the U.S. Air Force’s China Aerospace Studies Institute. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Air Force, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

Image: Voice of America