Sabotage and War in Cyberspace

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is a terrible throwback to attrition warfare. Having failed in their opening salvo against Kyiv, Russian forces have settled into a grinding campaign in other parts of the country, using artillery bombardments in advance of slowly moving infantry. There is nothing elegant about their approach. After years of speculation about hybrid warfare and grey-zone tactics, Russia has reverted to form. Its offensive cyberspace operations have been particularly marginal to its conventional military effort. Open sources suggest that Russia has rarely used destructive malware since the February invasion. Over the same period it fired millions of bullets, artillery shells, and rockets, with devastating effect. As Michael Kofman put it, “This is a heavy metal war.”

This has surprised many observers, who thought the war would follow a different path. I was one of them. I suspected that Russia would open the war with a burst of cyberspace operations designed to hobble Ukrainian communications and make it impossible for Kyiv to organize a coherent defense. It’s easy to see the allure of such a concept, though I doubted it would succeed because the technical demands are quite high. Nonetheless, Russian military doctrine stresses the importance of information dominance, and analysts have spent years sounding the alarm about the potential for large-scale digital disruption in the event of war. Instead, most Russian efforts appear to be related to espionage and propaganda, with only a smattering of sabotage.

Microsoft has issued two reports on Russian operations. Its data suggests that most Russian activities are about stealing information and influencing the public debate, not incapacitating information systems or causing physical harm. Russia may unleash such operations later, the authors warn, but so far, they have been largely absent. Indeed, it is telling that Microsoft devotes the lion’s share of its June report to Russian propaganda, detailing the ways in which Russian agencies pre-positioned fake stories before the war to make them seem more credible later. Such public methods are easier to track, to be sure, which explains part of why they receive so much attention. But if disruptive operations were so important to Russian cyberspace activities, we should at least see their residue.

The June report also suggests a correlation between cyberspace operations and conventional campaigns, highlighting a half-dozen instances in which malware moved on a target in advance of military forces. Yet the link is tenuous in some cases, and in others it appears that Russian cyberspace efforts were simply aimed at gathering information. Efforts to use malware to disable Ukrainian communications, or to cause harm to Ukraine’s foreign supporters, have been infrequent and largely inconsequential. There is little evidence in open sources that Russian cyberspace operations have had a meaningful effect on Ukraine’s combat performance. Nor have they had much effect on the international response. Cyberspace operations, in short, have not played a key role in this war.

Why not? Observers have offered a host of plausible explanations. Aid from the United States and the private sector may have provided a critical bulwark against digital aggression, as Microsoft suggests. Or perhaps Ukraine’s defenders were better than expected. Maybe Russia restrained its activities because it feared destroying the networks it would need after occupying the country. Maybe Russia withheld damaging operations against the West because it wants to use the threat of cyberspace attacks to coerce Ukraine’s supporters. Russian cyber activities might have been ineffective because they are too reliant on hackers whose activities the Russian state cannot fully control. Going on the offensive in cyberspace is harder than we thought for these reasons. Defenders have key advantages in a conflict, not least their ability to move information into the cloud and otherwise make their communications redundant.

There may be truth in these claims — it is too soon to tell. But there is a simpler explanation. Because cyberspace is an information domain, cyberspace operations are about gaining information advantages. Intelligence agencies scour the domain in search of details that may be useful to strategists, diplomats, and military leaders. They want to know about the strength and disposition of enemy forces, as well as the capabilities and intentions of third parties. In this sense, Russian cyberspace activities are no different from intelligence gathering in past conflicts. Espionage — collecting and interpreting secret information to give political and military leaders decision advantage — is key. Sabotage remains secondary.

The Logic of Wartime Sabotage

“Everything in war is very simple,” Clausewitz tells us, “but the simplest thing is difficult.” The reason is friction: the routine bureaucratic hiccups that affect organizational performance. Armies are large, armed bureaucracies, subject to the same day-to-day annoyances as any other: broken machines, sick soldiers, paperwork errors, flat tires, and so on. Military leaders strive to coordinate the efforts of many individual warfighters, but normal friction gets in the way. In peacetime this is frustrating but tolerable. During a conflict it becomes much worse, as everyday glitches are amplified under the confusion and stress of organized violence.

Wartime saboteurs seek to weaponize friction. Their actions are often covert, meaning that the victim does not realize that “normal” malfunctions are actually by design. In some cases, this can include introducing faults during the design and production process of wartime materials. Sabotage may also include quietly disabling communication technologies, making it difficult for enemies to follow events and organize their response. The heart of sabotage is forcing dysfunction into adversary capabilities and organizations. Sabotage is not about winning a fair fight. It is about making the fight unfair.

In some cases, sabotage can include more subtle methods of eroding adversary efficiency and morale. The World War II Office of Strategic Services, for example, encouraged civilians behind enemy lines to engage in a kind of inconspicuous sabotage. They did not ask civilians to take extraordinary risks to demolish factories. Instead, they called for an accumulation of inconveniences that would increase friction within them. Laborers could do this by “starting arguments” and “acting stupidly.” Administrators could go further. The office offered memorable guidance on how to do so:

Make “speeches.” Talk as frequently as possible and at great length. Illustrate your “points” by long anecdotes and accounts of personal experiences. … When possible, refer all matters to committees, for “further study and consideration.” Attempt to make the committees as large as possible — never less than five … Bring up irrelevant issues as frequently as possible. Haggle over precise wordings of communications, minutes, resolutions. … Refer back to matters decided upon at the last meeting and attempt to re-open the question of the advisability of that decision.

Whether this activity had measurable effects on the war’s outcome is difficult to answer, given the enormous scope and complexity of the conflict. Some sabotage operations clearly succeeded on their own terms, though their impact on the war itself was marginal. Because the strategic logic of sabotage is based on the cumulative effect of many small actions over time, it is inherently hard to assess its impact. Recent work on sabotage makes the similar argument that it is tactically useful but strategically indecisive. Technological changes, however, have raised the prospect of more dramatic results.

Sabotage in Cyberspace

Cyberspace, we are told, is a playground for saboteurs. The domain is gigantically complex, making it easy for attackers to lie in wait. It is also interconnected, making it possible for attackers to operate from afar at little risk. Saboteurs have a lot of options when they choose to go on the offensive, ranging from simple tactics like website defacement and denial-of-service attacks, to more ambitious operations to disable physical systems. Their choices have increased over the last two decades, as modern militaries have increased their use of information networks to coordinate their actions. Digital dependence allows them to work more efficiently, knitting together disparate forces and providing a mechanism for sharing intelligence in real time, but it also makes them more vulnerable to cyberspace sabotage.

Defense against cyberspace sabotage is difficult for many reasons, not least the sheer number of networks and machines needing protection. Overlapping links between military organizations, defense firms, and other contractors also create possible security risks. The huge amount of software code that underwrites military hardware inevitably contains flaws, some of which are unknown to defenders until they are exploited. Human error compounds these problems. Lapses in operational security and cyber hygiene make it difficult for military and defense organizations to guard against opportunistic saboteurs.

Observers have long believed that cyberspace is ripe for offensive action, implying that sabotage will have outsize effects in future wars. The main advantages seem to lie with the attacker, and recent books have stressed the new dangers of cyber attacks. David Sanger of the New York Times calls cyberspace operations “the perfect weapon,” cheap and easy tools for debilitating the infrastructure on which we all depend. Publishing before the war in Ukraine, Sanger echoed the common belief that future wars would star with a cyber barrage. Nicole Perloth, also of the Times, warns that such attacks are potentially cataclysmic. Her recent book, which pays close attention to the Russian threat, is called This is How They Tell Me The World Ends.

Yet cyber security researchers have repeatedly taken aim at this assumption. Low-impact sabotage (e.g., denial-of-service attacks) may be relatively easy to achieve, but more ambitious operations are not. These depend on exquisite intelligence, along with specially tailored malware that takes advantage of specific vulnerabilities. Access to target networks is often tenuous, meaning that even well-planned operations may never get off the ground. Saboteurs risk exposure as their objectives grow, meaning that defenders are more likely to spot planning for substantial attacks and take actions to defend themselves. Successful operations thus require a combination of time, money, skill, organization, and luck.

States in conflict are likely to take extra steps to defend themselves against cyberspace operations, making wartime sabotage especially difficult. They can build redundant communications to ensure their reliability and harden existing networks. They can move data onto the cloud and away from domestic servers, which are vulnerable to physical destruction. And they can call on foreign allies and private firms for technical support. (Microsoft stresses this point in its latest report on the war in Ukraine.) The normal barriers to public-private cooperation prove less daunting when civilians are in real danger. For all these reasons, wartime cyberspace operations may prove to be relatively inconsequential, just as sabotage was of marginal effect in past conflicts. Perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised that most Russian cyberspace activities have served other purposes.

Back to Basics

Cyberspace was supposed to elevate the role of sabotage in war. Indeed, the existence of interlinked communications networks suggested opportunities for crippling information attacks, an irresistible prospect for leaders seeking quick and decisive victory. Sabotage, long a sideshow in conventional wars, might under these conditions take center stage. This has not occurred in Ukraine, however, where the war has descended into a contest of attrition and will. But this doesn’t mean that Russia has been inactive in cyberspace during the war. Quite the opposite: It has been quite aggressive in terms of espionage and propaganda, both in Ukraine and abroad.

These activities have a long history. Military forces have employed spies for millennia, seeking information on the size and disposition of their enemies, along with foreknowledge of enemy intentions. Access to secrets can enable battlefield victories, at least in theory, because they allow commanders to array their defenses against likely attacks and because they reveal opportunities to go on the offensive. Scholars have long debated the value of intelligence in war relative to material capabilities. This debate is somewhat misleading, however, because information improves the efficiency of military force rather than replacing it. The question is not whether intelligence is decisive but how it aids the use of force.

Cyberspace espionage for military purposes is particularly appealing. Highly interconnected communications networks provide more entry points for collection, and concentrated data depositories mean that successful intrusions can release extraordinary amounts of information. The scale in cyberspace is much larger, as Michael Warner notes. Successful espionage offers more than dribs and drabs about the enemy — it has the potential to offer a fine-grained view of enemy capabilities and intentions. All of this increases the risk of overloading military bureaucracies with more data than they can bear. Defense officials can reduce collection to alleviate the burden, or they can search for better information-processing technologies. If they choose the former, what kinds of collection are they willing to abandon? If they choose the latter, what sort of technologies do they have in mind? And how does their decision improve the use of secret intelligence for conventional military operations?

These questions are not terribly exciting, at least not compared to spectacular acts of sabotage. But we might learn something about the practical use of cyberspace operations by asking them. Russia’s experience in Ukraine offers a cautionary tale about expecting too much from cyber attacks, but it may yet reveal lessons about intelligence and war.

Joshua Rovner is an associate professor in the School of International Service at American University.

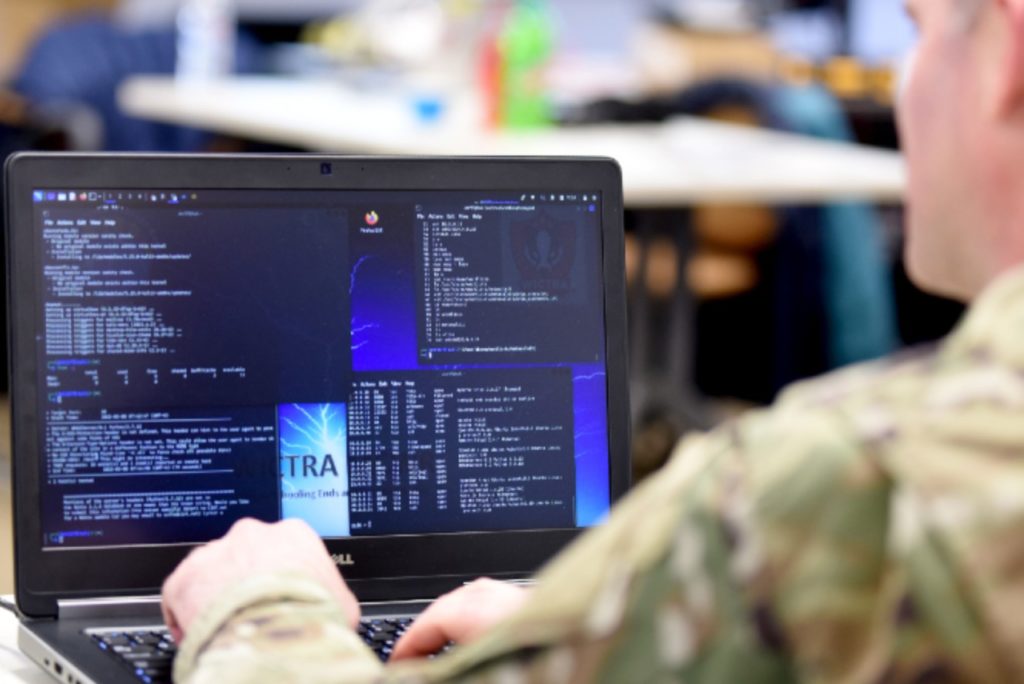

Image: U.S. Air National Guard photo by Master Sgt. David Eichaker