Show Me the Money: Boost the Pacific Deterrence Initiative

Eight years ago, Vladimir Putin’s first invasion of Ukraine and illegal seizure of Crimea forced the United States to get serious about deterrence in Europe — and pay for it. In the proceeding years, the United States dedicated nearly $30 billion to the European Deterrence Initiative to reinvigorate U.S. military posture and capabilities on the continent.

Two years ago, Congress decided on a bipartisan basis that a similar effort was needed in the Indo-Pacific region — not to respond to a war, but to prevent one. And so, it established the Pacific Deterrence Initiative. But a legislative compromise meant the initiative did not provide dedicated funding like its European predecessor did, or as its advocates had originally intended. Instead, the Pacific Deterrence Initiative was created as a “budget display,” a transparency measure meant to capture significant Indo-Pacific efforts across the defense budget and enable Congress “to track these efforts over time, assess their progress, and make adjustments when necessary.”

Even without dedicated funding, the initiative has served as a political catalyst, particularly on Capitol Hill. It has provided Congress a regional lens through which to interpret a sprawling defense budget. It has broadened understanding of what is needed to maintain U.S. military advantage in the Indo-Pacific. And it has made possible otherwise unlikely policy outcomes, such as funding for missile defense in Guam that languished for years prior to the initiative’s establishment.

That said, the political boost of the Pacific Deterrence Initiative is wearing off, and the limits of the initiative as a budget display are increasingly evident. Congress and the Pentagon have yet to provide the same kind or level of funding in the Indo-Pacific that has proven “absolutely vital” in Europe. Congressional increases to the defense budget in recent years have not been effectively targeted or implemented to address capability gaps and capacity shortfalls in the Indo-Pacific on a sustained programmatic basis.

As it considers fiscal year 2023 defense authorization and appropriations bills, Congress should not merely add money to various accounts that compose the Pacific Deterrence Initiative for a single year. Instead, it should transform the initiative into a dedicated appropriations account — one whose funding is separate from and in addition to the budgets of the military services, managed directly by the Office of the Secretary of Defense in consultation with U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, and competitively allocated to the programs, projects, and activities that best advance joint requirements in the Indo-Pacific theater.

Timing and Strategy

Why does the Pacific Deterrence Initiative need to change now? The simple fact is that the current speed, scope, and scale of change in the Department of Defense is inadequate to ensure credible deterrence in the Indo-Pacific.

As China’s military capability and capacity have grown rapidly and simultaneously, the Pentagon has spent the last 10 years (with few exceptions) sacrificing near-term investment in readiness and posture for long-term investment in modernization and research and development. It has sought to build a “future force,” whose date of arrival moves further and further away (2025, 2030, 2035 …) even as the date of concern about Beijing’s military modernization and its ambition to control Taiwan creeps closer and closer (2049, 2035, 2027 …). Even as speculation mounts thatXi Jinping intends to achieve unification with Taiwan during his tenure and Beijing is more seriously weighing initiating a conflict, the Pentagon continues the same course. Meanwhile, U.S. military capabilities and posture in the Indo-Pacific region have changed only marginally in the last decade. New operational concepts have been introduced, but the joint capabilities necessary to execute them remain under-resourced: posture, logistics, integrated air and missile defense, persistent intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance, command and control, and more.

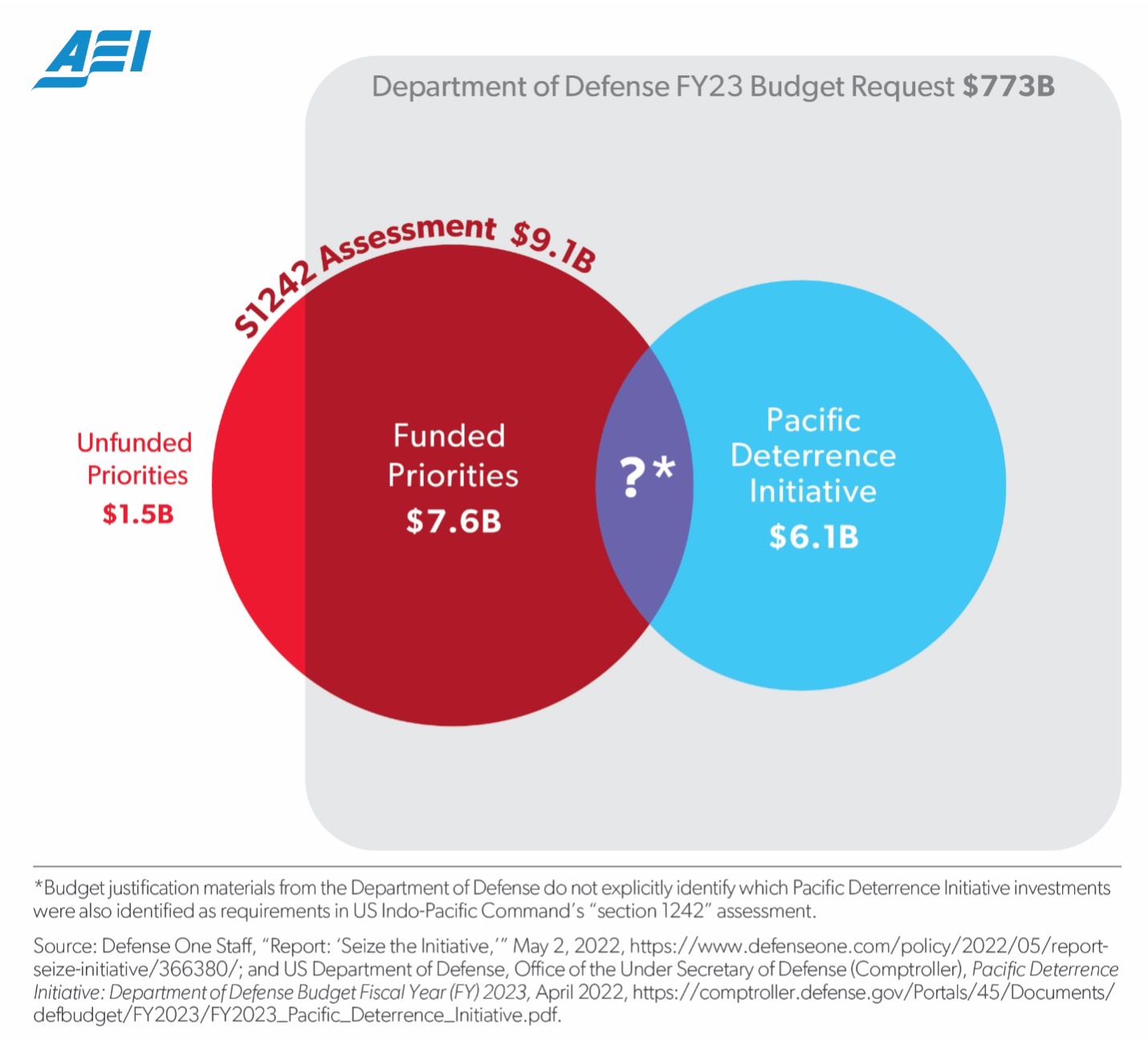

The Pentagon’s fiscal year 2023 request for the Pacific Deterrence Initiative epitomizes the fundamental lack of urgency, ambition, and imagination necessary to meet the pacing challenge posed by China. Funding for the initiative is inadequate. The Pentagon’s $6.1 billion request for the Pacific Deterrence Initiative marks a $1 billion decrease from last year’s congressionally authorized topline for fiscal year 2022. The Pentagon’s request left U.S. Indo-Pacific Command with $1.5 billion in unfunded requirements. Moreover, the Pentagon projected that the initiative would shrink by more than a quarter to $4.4 billion by fiscal year 2027 — a portentous date by which China aims to accelerate its military modernization with an eye on Taiwan.

Too much of the Pentagon’s request for the Pacific Deterrence Initiative reflects the cost of sustaining rather than improving current capabilities and posture. A sizable portion of the initiative funds maintenance of existing facilities, operation of steady-state forces, and execution of legacy posture initiatives. No notable shifts of forces west of the international date line are funded. No major changes are evident in the scale or scope of security cooperation activities with regional allies and partners. And so on.

The $1.2 billion in military construction funds requested in the Pacific Deterrence Initiative request does little to close the Pentagon’s persistent “say-do” gap on regional force posture. Despite the Pentagon’s focus on a more distributed posture, over three-quarters of posture funding in the initiative is concentrated in Japan and Guam — more than a third of that at Kadena Air Base alone. In a familiar pattern, projects in the Second Island Chain, Oceania, and Southeast Asia account for a small portion of investment.

Meanwhile, only a small percentage of posture funds in the Pacific Deterrence Initiative request represents new investment in posture directly tied to making U.S. forces west of the international date line more capable, distributed, and resilient. Instead, some projects mark the continuation of posture plans long pre-dating the initiative. For example, the effort to build a new airfield at Tinian — funded at $191 million in the budget request — has been underway since 2012. Other projects simply don’t belong in the initiative, such as the $316 million for three projects associated with the Defense Policy Review Initiative to relocate Marines from Okinawa to Guam. Completing this as quickly as possible is a political imperative for the U.S.-Japan alliance. But it will not meaningfully improve U.S. deterrence posture in the region and, thus, does not advance the objectives of the Pacific Deterrence Initiative.

The Pacific Deterrence Initiative includes significant “planning and design” funds for future posture projects in the Indo-Pacific. But until backed by real military construction funds, these “planning and design” funds are the Pentagon equivalent of “look but don’t touch.” When it comes to investing in the more capable, distributed, and resilient force posture we need in the Indo-Pacific, the answer still seems to be as it was for Macbeth, “Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow.”

Posture is not the only area for which the Pentagon requested questionable funding in the Pacific Deterrence Initiative. For example, the initiative includes a request for over $300 million in Army funding related to integrated air and missile defense: modification of Patriot missiles, modernization of Sentinel radars, and research and development funds for the Army’s Integrated Air and Missile Defense Battle Command System. But budget materials draw no direct connection between these funds and activities in the Indo-Pacific theater. By contrast, funding in the European Deterrence Initiative for procurement of Patriot Missile Segment Enhancement missiles is specifically associated with a U.S. European Command munitions starter set to be pre-positioned in theater. Congress should press the Army on whether funding included in the Pacific Deterrence Initiative is contributing specifically and directly to Indo-Pacific operational needs.

Consider another example. At $1 billion, funding for the Strategic Capabilities Office (specifically, its Advanced Innovative Technologies program element) makes up one-sixth of the Pentagon’s Pacific Deterrence Initiative request. In recent years, the Strategic Capabilities Office has appropriately focused many of its technology development, demonstration, and transition efforts on China . However, the Pentagon only identified one specific project funded in the Pacific Deterrence Initiative — the Hypervelocity Gun Weapons System at $151 million — in fiscal year 2023. Congress needs to scrutinize the remaining $850 million to ensure these projects are directly focused on operational challenges in the Indo-Pacific and, if appropriate, have identified transition partners with intent to field these capabilities in theater in near term.

Put the “Budget Display” in the Rearview Mirror

Why would a dedicated appropriations account prove more effective than a budget display in effectively prioritizing the Indo-Pacific requirements? The establishment of the Pacific Deterrence Initiative as a budget display was a worthwhile compromise that has achieved important initial progress. But unless and until Congress transforms the initiative into a dedicated appropriations account, the initiative’s weaknesses evident in this year’s budget request will persist.

A budget display will not fundamentally affect how the Pentagon approaches resourcing theater requirements. The Pentagon builds its Pacific Deterrence Initiative request by conducting a post-hoc labeling drill in which the Pentagon determines which investments already planned, programmed, and budgeted meet the objectives of the initiative. In other words, inside the Pentagon, the Pacific Deterrence Initiative does not drive budget decisions, but reflects them. This is why the Pentagon’s request for the initiative reads as a grab-bag of investments — a hastily-composed Pacific anthology lacking indicia of intelligent design and composed of fragments torn from loosely related works. A dedicated appropriations account with bipartisan support from Congress would force the Pentagon to adopt a more substantive approach to developing and implementing the Pacific Deterrence Initiative as part of its Planning, Programming, Budgeting, and Execution cycle. This would not only elevate the Indo-Pacific as driving force in Pentagon planning, it would also improve the Pentagon’s ability to absorb and execute congressional appropriations increases above the budget request intended for the Indo-Pacific.

A budget display will not sufficiently incentivize the military services to shift investment from platform-centric modernization toward joint and enabling capabilities in the Indo-Pacific theater. Seized by their own internal budget pressures, the services (with the possible exception of the Marine Corps) will not sacrifice significant sums of their own budget authority for theater-specific warfighting needs — not amid persistent budget uncertainty fanned by the Biden administration’s diminishment of defense, not while confronting the crushing modernization bills of the “Terrible 20s,” not with service cultures organized around platform-centered operational communities, and not with pernicious pockets of parochialism lurking on Capitol Hill.

Anticipated growth in Indo-Pacific requirements makes adequate resourcing from the military services under current budgetary constraints even less likely. In its independent assessment to Congress, U.S. Indo-Pacific Command identified $9.1 billion in theater requirements for fiscal year 2023, of which the budget request included $7.6 billion. But as it aims to against China in the coming years, U.S. Indo-Pacific Command projects its requirements over fiscal years 2024–2027 to average $16.7 billion annually. This substantial increase is driven by the command’s intensified focus on cyber and space capabilities as well as its previously articulated and increasingly refined posture and infrastructure needs. To put it mildly, earning support for theater requirements at this scale will be an uphill battle inside the Pentagon regardless of the administration in power.

Under these circumstances, the military services are incentivized to keep theater-specific spending on joint requirements to a minimum while broadly interpreting spending on existing programs, projects, and activities as meeting the objectives of the Pacific Deterrence Initiative. This protects funding for service priorities while mollifying Congress by filling the initiative’s budget display to some acceptable level. But as the fiscal year 2023 budget request demonstrates, it dilutes the focus and quality of the initiative.

A dedicated appropriations account, controlled by the Office of the Secretary of Defense and competitively awarded, would reverse these incentives. Instead of trying to preserve budget authority to spend according to their preferences, the military services and other defense agencies would be fighting to win new budget authority. Instead of a loose interpretation of service priorities as theater requirements, a competitive dynamic would tighten focus on Indo-Pacific needs. Officials in the Pentagon and in U.S. European Command used to emphasize keeping the European Deterrence Initiative “clean” — that is, laser-focused on European requirements and free from service programs, projects, and activities that were generally applicable across theaters. A dedicated appropriations account for the Indo-Pacific would have a similar disciplinary effect.

Everyone’s a Critic?

Skepticism in the Pentagon and on Capitol Hill prevented the Pacific Deterrence Initiative from becoming a dedicated appropriations account two years ago. What did opponents say then, and what are they saying now?

Back in 2020, the Trump administration expressed concern that the Pacific Deterrence Initiative would “limit DOD’s flexibility.” Indeed, some in Congress felt the same way about their own flexibility in wielding the power of the purse. Put simply, a dedicated appropriations account for the Pacific Deterrence Initiative renders some portion of defense funds less fungible for defense officials or lawmakers to move around and use as they see fit. That flexibility might be worth preserving if Indo-Pacific requirements were already effectively prioritized. But they are not. Some limited flexibility is justified to ensure a level of funding more consistent with theater needs.

Two years ago, a checkered past with appropriations accounts outside the base defense budget spoiled both executive and legislative branch appetites for dedicated Indo-Pacific appropriations. The Overseas Contingency Operations account was widely panned as a slush fund, openly used to circumvent sequestration. Neither the Trump administration nor progressive Democrats wanted to see a repeat. For a brief period, the European Deterrence Initiative also came under scrutiny from the likes of the Government Accountability Office for lack of prioritization, failure to account for sustainment costs, and insufficient long-term planning. While these issues were subsequently addressed, they colored perceptions of standalone regional initiatives. A dedicated appropriations account for the Pacific Deterrence Initiative would no doubt require disciplined planning in the Pentagon and robust oversight from the Congress. Both are possible. And recent experience has provided lessons that can be incorporated from the outset to ensure successful execution in accordance with congressional intent.

Another concern is that dedicated appropriations would give too much power to U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, or somehow prevent the Pentagon from effectively auditing the command’s requests. This charge is spurious. U.S. Indo-Pacific Command has and should have a prominent voice in articulating Indo-Pacific requirements. Indeed, Congress has recently seen fit to boost that voice by requiring in law an annual independent assessment from the command on theater requirements and resourcing. While this assessment is as good a summary of Indo-Pacific needs as any, it is not gospel. It is subject to the same debate inside the Pentagon and on Capitol Hill as any other aspect of the budget. Moreover, a dedicated appropriations account should remain under the control of the Office of the Secretary of Defense and should be awarded through a competitive process that provides an opportunity for a variety of Pentagon stakeholders to be heard.

Finally, some skeptics feel the Pacific Deterrence Initiative should be discarded because it is too narrow and fails to fully capture the Pentagon’s real level of investment activities geared toward the China challenge. Rather than focus on specific categories of investment, these critics argue Congress needs to see the defense budget in its full context, including the hundreds of billions of dollars spent on procurement, advanced technologies, and readiness funding.

It is true that the Pacific Deterrence Initiative does not capture all Pentagon spending related to China. That’s because it was not intended to. Congress designed the initiative — to borrow a phrase — to bring balance to the force, correcting the Pentagon’s tendency to overemphasize procurement of major weapons systems while under-resourcing joint and enabling capabilities, particularly those required by new operational concepts.

For example, lawmakers argued in these pages two years ago that “it doesn’t matter how many F-35s the military buys if very few are stationed in the region, their primary bases have little defense against Chinese missiles, they don’t have secondary airfields to operate from, they can’t access pre-positioned stocks of fuel and munitions, or they can’t be repaired in theater and get back in the fight when it counts.” This insight still rings true today. Services need no special direction to buy major platforms. But it appears such direction is necessary to meet joint requirements in the Indo-Pacific. That is what a dedicated appropriations account will provide.

To be clear, the Pacific Deterrence Initiative — whether as a budget display or a dedicated appropriations account — is not a panacea. It will not fully mitigate the consequences of the Goldwater-Nichols “divorce between force providers and force employers,” or mend the “broader schism in the Pentagon processes between near- and long-term planning.” Congress must continue to pursue more fundamental reforms aimed at more effectively developing, fielding, integrating, and posturing military capabilities to be employed by the combatant commands. This is work that cannot be outsourced to commissions but must be the sustained enterprise of congressional oversight and legislation.

In Search of a Pivot

It took Putin invading Ukraine and annexing Crimea for the United States to get serious about deterrence in Europe and pay for it. Now for a second time, we’ve seen Putin wage war against Ukraine. We’ve been reminded that peace is not guaranteed, that no continent is beyond the reach of war, that some tyrants believe conquest still pays, and that power politics are a reality of our present, not just our past. Must we wait for tragedy in the Indo-Pacific before we respond with the urgency, ambition, and imagination that is required? It’s time to put real money behind the Pacific Deterrence Initiative before it’s too late.

Dustin Walker is a non-resident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. He was a professional staff member on the Senate Armed Services Committee from 2015 to 2020, during which he served as the lead adviser to Sen. Jim Inhofe, R-Okla., on the development of the Pacific Deterrence Initiative.

Image: U.S. Navy Combat Camera photo by Mass Communication Specialist 1st Class Stacy D. Laseter