War by Timeframe: Responding to China’s Pacing Challenge

The Latin adage “si vis pacem, para bellum” states that if you want peace, prepare for war. But doing that successfully is much easier if you know when the war might occur.

As it drafts its new national defense strategy, the Biden administration has argued that China is the pacing challenge that should drive U.S. military planning moving forward. However, to plan for a conflict with China — most likely over Taiwan — Washington needs to think harder about the timeframe in which it is most likely to happen. The default U.S. defense strategy is to hedge against the risk of war in all timeframes. In a world of limited budgets, though, it is not possible to maximize U.S. capabilities in all time periods simultaneously. This means that, despite the uncertainty of even the best risk assessments, Washington will need to place bets to sustain its defense leadership in the Indo-Pacific. America may need “more” to deter and defeat China, but the right “more” depends on the timing.

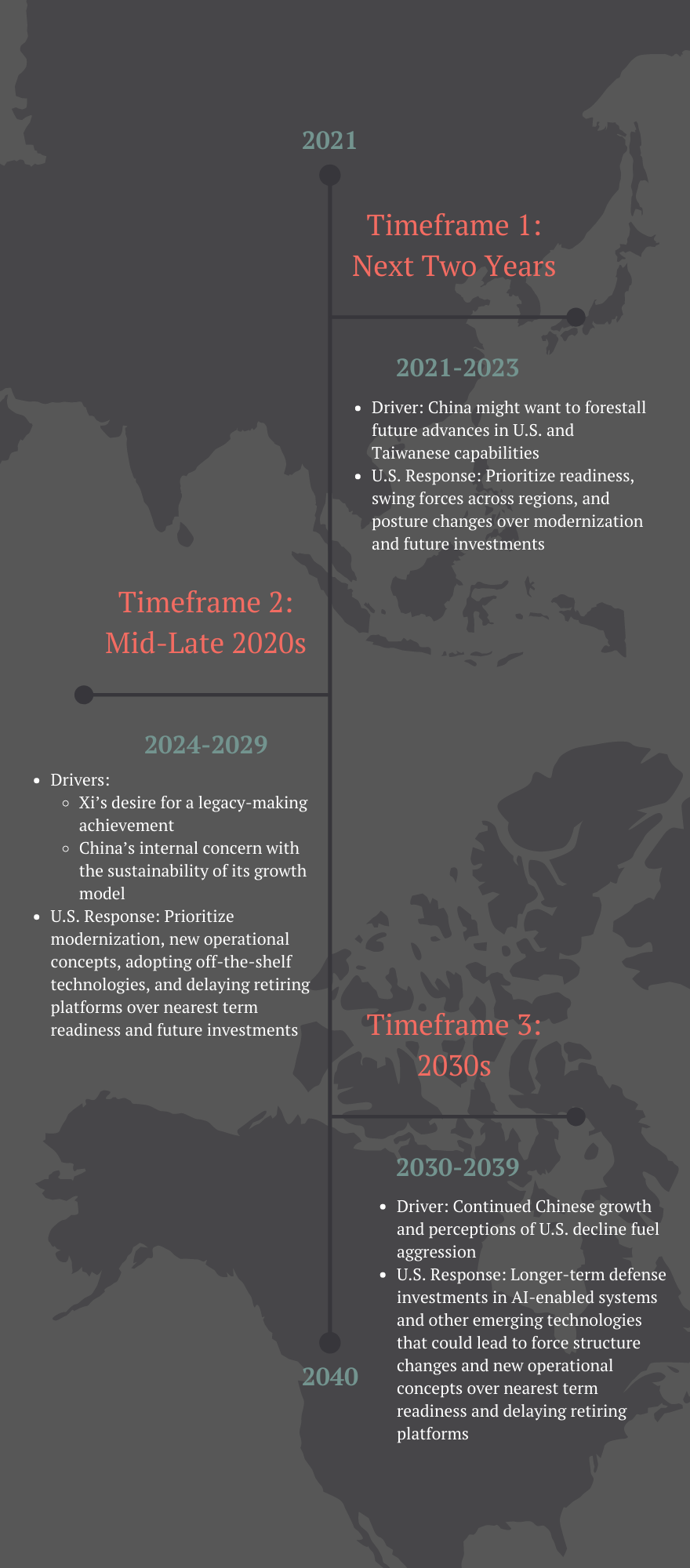

If war over Taiwan is imminent in the next two years, the United States should emphasize readiness and posture over modernization and future investments. If war is most likely later in the 2020s, new warfighting concepts, modernization, adapting off-the-shelf technologies, and delaying retiring some older platforms should become the priorities. If war is most likely in the 2030s or beyond, longer-term defense investments, such as AI-enabled systems that require bigger changes to force structure, combined with innovative operational concepts, should be prioritized.

Success in any timeframe will require new operational concepts, posture changes that complicate Chinese planning, and greater coordination with allies and partners. To make matters more difficult, if the United States is fully transparent about the timeframe in which it thinks war is most likely and how it is investing, China will adapt, increasing the risk of aggression in other time periods. This means that greater opacity about Department of Defense planning and investment priorities is essential. While complete opacity is neither realistic nor desirable in a democracy, some degree of opacity could complicate Chinese planning across all time periods, making deterrence more likely to succeed — and victory for the United States and its allies and partners more likely if deterrence fails. Threading this needle will require greater integration of intelligence analysis into the national defense strategy. It will also require making real choices in that document to direct military service planning.

Potential Timeframes

Everyone hopes that a U.S.-Chinese war will not occur. But in the context of great-power competition, concerns are growing. At present, there are competing perspectives on when U.S.-Chinese conflict is most likely, and what the United States should do in response. The most proximate potential timeframe for war is in the next two years. A massive surge in Chinese air force incursions into Taiwanese airspace in early October may demonstrate that the Chinese are already planning for war in the near term. Ongoing U.S. and Taiwanese investments in advanced munitions, modified Virginia-class submarines, Taiwanese procurement of anti-ship cruise missiles, and other programs would substantially raise the costs of a Chinese invasion further in the future. Knowing this, China could choose to invade before even before their own planned readiness point to forestall future advances in U.S. and Taiwanese capabilities.

A second possible timeframe for war envisions China acquiring the ability to effectively threaten Taiwan in the middle to late 2020s. Xi’s desire to for a legacy-making achievement, and concerns about the sustainability of the Chinese economic growth model, may drive the point of maximum risk to the latter half of the 2020s, since the Chinese will view their window as closing after that. In March 2021, Adm. Phil Davidson, then the head of U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, said that China has the intent, and increasingly the capability, to threaten Taiwan “during this decade, in fact in the next six years.” Later that month, while not giving a specific timeframe, his successor, Adm. John Aquilino, said the threat of a Chinese invasion is “closer than most think.” Rear Adm. Mike Studeman stated in July 2021 that there is “clear and present danger” now and within the 2020s. And some interpret the Department of Defense’s annual report on Chinese military power as saying that China seeks to acquire the ability to militarily coerce Taiwan with the credible threat of invasion by 2027.

A third possible timeframe sees the maximum risk of war as happening in the 2030s or beyond, since the Chinese economy is likely to continue growing. In contrast to Davidson, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Mark Milley argues that while China wants to develop the capability to invade Taiwan by 2027, it does not actually intend to do so — meaning there is more time before the period of maximum risk. In this case, the People’s Liberation Army would face limits on their operational capacity until the 2030s, and/or China’s economic challenges would not generate pressure to fight now. China might also act later so it can first grow its power projection capability to limit the effectiveness of a blockade response or horizontal escalation. It also might choose to wait if its economic power continues to grow and it sees the capacity to defend Taiwan declining.

The Right Responses?

Domestic political constraints make defense budget limits inevitable, meaning it is not possible to simultaneously maximize readiness for today, modernization of force structure for tomorrow, and investments in emerging technologies for the future. So what can the U.S. do?

Short Term

If the risk of Chinese aggression is most likely in the coming two years, then reinforcing America’s forward presence while distributing forces more broadly in the Indo-Pacific would be the best response. In this scenario, the United States should invest in readiness and the ability to operate its current force, buy as many smart munitions as possible with emergency authorizations, and prepare for imminent conflict. It would be nearly impossible to speed up production of submarines as construction timelines recover from the impact of COVID-19. But the United States could look to mature technologies ready for deployment, leveraging prior Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency programs. The United States could also seek to reinforce Taiwan’s defenses with anti-ship cruise missiles, and it could rapidly deploy U.S. troops to Taiwan to convince Beijing that Washington is serious about Taiwan’s defense.

If war is in fact imminent in the next two years, there is almost no time for investments in emerging technologies to pay off, or even to integrate many commercial, off-the-shelf capabilities. Instead, the United States would have to go to war with its current force structure and operational concepts, potentially with some changes in posture. Longer-term investments like modernization would likely have their timelines pushed back.

Medium Term

Alternatively, what if the maximum risk period for a U.S.-Chinese conflict runs from roughly 2024 to 2029? Some have already made the point that, in this scenario, the United States would need to invest in “more conventional hard power — more ships, more long-range missiles and more long-range bombers in the Indo-Pacific,” rather than in emerging technologies with uncertain reliability. In addition, if war is most likely in the latter part of the 2020s, the Biden administration should focus on the types of efforts envisioned by the Pacific Deterrence Initiative. This would involve increasing protection for Guam, building out runways and pre-positioning equipment in additional locations throughout the Pacific to create a more distributed force structure, and speeding and growing purchases of smart munitions.

In this scenario, the Department of Defense should also shift how it thinks about using existing capabilities, including increasing efforts by the Strategic Capabilities Office to use off-the-shelf commercial technologies as force multipliers for existing U.S. assets. It could also think about novel ways to employ capabilities slated for retirement: placing Ticonderoga-class cruisers near U.S. military bases to serve the function of Aegis-ashore systems, or using older submarines as missile batteries.

Inevitably, this approach comes with trade-offs. The emphasis on new equipment and new operational concepts for today’s capabilities would come at the expense of emerging technologies and experimentation that could reshape military power in the 2030s. It also might not solve the readiness and posture challenges for the nearest-term scenario.

Long Term

Finally, if the maximum risk of war is in the 2030s and beyond, there is time for the American military to plan ahead, investing more in emerging technologies and experimenting with new operational concepts in ways that substantially shift U.S. posture and the size and shape of the American military in the Pacific. These investments could involve a greater reliance on AI-enabled capabilities, hypersonics, and shifts in force structure that emphasize swarms and mass over higher-cost, lower-quantity platforms. This approach could create more risk in the nearer term if resources or organizational focus are not available to make progress on posture challenges. The United States could seek to mitigate risk in earlier timeframes by shifting forces from other regions (thus taking more risk in those regions), or enacting acquisition reform that enables more rapid prototyping and deployment of new systems.

Strategies for All Seasons

Any assessment of the “most likely” timeframe for war will be necessarily uncertain. How can the United States hedge against the risk of war in every timeframe, even as it identifies priorities based on timeframe?

First, maintaining advantage requires organizational innovation, not just acquiring technologies. If the U.S. military simply moves forward incrementally, it will increase the risk of relative decline. Failure to develop new operational concepts, modernize forces with sufficient capacity, and invest in emerging capabilities will lead to a scenario in which the United States fights tomorrow’s wars with yesterday’s capabilities. Organizational change, which could require sizing and shaping the force in different ways, is necessary given the extent of the challenge China poses. Decreasing risk across multiple timeframes simultaneously will require acquisition reform to enable more rapid prototyping and deployment, new operational concepts, and changes in posture — all at once.

Second, more external opacity about how the United States thinks about the risk of war and designs its defense strategy and investment portfolio would help. There is always a dilemma when it comes to revealing and concealing capabilities. Revealing capabilities makes them more likely to deter aggression, but the capabilities cannot then surprise an adversary if a conflict occurs. Concealed capabilities cannot deter, but can offer the advantage of surprise in the event of a conflict. Concealing pieces of the U.S. defense investment strategy externally could help complicate Chinese planning, aiding U.S. efforts across time periods. There are some advantages, from this perspective, in focusing on the future but not revealing that focus too clearly. This could similarly apply to efforts to bolster Taiwanese defenses: Some opacity about what exactly the United States is supplying Taiwan, and in what quantity, could also complicate Chinese planning. Especially if war is likely in the short term, opacity could bolster Taiwan’s defenses by making China uncertain about what the United States has done to assist Taiwan, and what exactly Taiwan’s capacity might be.

Third, improving the ability of allies and partners to fight — and especially to strike Chinese assets in the case of attack — could raise the costs of aggression and theoretically help fill U.S. capability gaps. Delivering advanced platforms, as in the Australia-United Kingdom-United States (or AUKUS) deal, can take time, but these agreements serve as valuable signals in the short term. Similarly, building stronger ties with countries like Indonesia and tighter defense relationships with Singapore could signal U.S. support for the region immediately, while also improving these countries’ capabilities over time.

Another alternative would be for the United States to use the threat of nuclear weapons to deter the risk of conventional war, as it did with doctrines such as flexible response and massive retaliation during the Cold War. But whatever one thinks of the merits of this approach, it will not forestall the need for better conventional planning. This is all the more true as the Biden administration seeks to reduce reliance on nuclear weapons and China builds up its nuclear arsenal so as to prevent just such an approach.

Time to Decide

The United States should deter the risk of war with China and be prepared to defeat China if war occurs across all timeframes. New operational concepts and organizational changes will be critical to successfully hedging across timeframes. Increasing the striking power of allies and partners can further raise the costs of action for China.

The challenge does not stop there. To deter or defeat a Chinese attack on Taiwan or other forms of aggression in the Indo-Pacific, Washington should assess when this is most likely to occur and plan accordingly. Yet Chinese diplomatic and military reactions to U.S. defense investment strategies will naturally shift the timeframe in which conflict is most likely, and what would happen if a conflict occurred. Bolstering US capabilities in the present could decrease the probability of war today while pushing risk more into the future. Conversely, bolstering capabilities in the long term could increase the short-term risk. This means intelligence assessments and timeframe estimates should not be static. The U.S. intelligence and defense communities will have to work together to integrate updated assessments into a more dynamic defense planning process. It also means that Washington should not let Beijing read its entire defense strategy playbook. Greater opacity about defense planning and investment priorities (to the extent plausible and desirable in a democracy) could help the United States prevent China from adapting to U.S. defense investments by prioritizing planning for war in other time periods. This is important because a Chinese decision to go to war would not just be about when Beijing believes it is ready, but also about whether Beijing believes waiting will increase its relative strength.

By predicting the pace of China’s pacing challenge, Washington can ensure that Beijing doesn’t conclude it has found the right time to attack Taiwan in the next two decades. In other words, if you want peace, prepare for war in the appropriate timeframe.

Michael C. Horowitz is Richard Perry Professor and director of Perry World House at the University of Pennsylvania. He is also senior fellow for defense technology and innovation at the Council on Foreign Relations. You can find him on twitter @mchorowitz. Thanks to Katrina McDermott and Jared Rosen for research assistance, and Lauren Kahn for the graphic. All fault for errors lies with the author.

Image: U.S. Navy (Photo by Mass Communication Spc. 3rd Class Andrew Langholf)