A Dysfunctional Peace: How Libya’s Fault Lines Were Redrawn

Mashroue al-Hadhba, an avenue running through Tripoli’s southern outskirts, bustles with open shops and service businesses. The asphalt is freshly done and throngs of people crowd its bakeries and hardware stores. Apart from the bullet and missile holes sullying the building facades, the scene from late December last year showed scarcely any sign of the terrible violence and displacement that afflicted residents here, when the broad street was part of the front line in a fierce battle for the Libyan capital from 2019 to 2020.

But just as memories of that internationalized civil war, which killed approximately 5,000 Libyans, are already fading, so too is the Libyan public’s hope for general elections. High-quality billboards drummed up voter registration, but the bogged-down electoral process no longer featured as a topic of casual conversation, even in coffee shops. As early as three or four weeks before the much-publicized U.N.-promoted deadline of Dec. 24, 2021, most Libyans understood that their country’s National Elections Commission was stuck. Though voters’ cards were distributed across the nation, polling stations were erected in every municipality, and tens of millions of public dinars were spent on logistics and databases, no vote could go ahead.

Among several hurdles, the greatest was the exceedingly weak character of the electoral laws that a small group of MPs — led by the Egyptian-backed Speaker of the House of Representatives, Aqila Saleh — designed and rammed through without a proper parliamentary vote. But the 78-year-old easterner and presidential hopeful is hardly the only influential politician in Libya who contributed to the elections’ failure by acting disingenuously: Almost all of them did, to some extent. Their incentive to sabotage the electoral process grew further pronounced in November, when Saif al-Islam, the late autocrat Muammar Qadhafi’s son, unveiled his intention to run for president, making the situation intolerably unpredictable for the other candidates.

In the absence of elections, much less legitimate mechanisms — perhaps even armed clashes — will shape what comes next. Libya has known no sustained exchange of fire since June 2020, but the relative normalcy, which the population has become used to, may fall prey to the machinations of a tiny minority of privileged Libyans absorbed by their pursuit of more power, affluence, or impunity.

Shallow Reconciliations and New Rivalries

The fault lines of Libyan politics have shifted since the wealthy, yet embattled, nation last commanded the international press’s attention. A bitter divide now separates the northwestern factions, who, back in 2019 and 2020, fought alongside each other to resist forces loyal to Khalifa Haftar, the rebel commander based 650 miles to the east. Almost three years after he ordered his doomed attack on Tripoli, the specter of Haftar’s past military campaigns and unresolved hunger for territorial expansion continue to divide Libyans. But at this precise juncture, incumbent Prime Minister Abd al-Hamid Dabaiba, who hails from the major western port city of Misrata, is the most polarizing political figure to the nation’s elites.

Through a raised-hands vote on Feb. 10, the House of Representatives appointed a new prime minister-designate: Fathi Bashagha, a former interior minister and famed revolutionary leader from the same hometown as Dabaiba. Several urban centers in Tripolitania, including the capital and Misrata itself, are currently split by the question of whether Dabaiba or Bashagha should be in the prime minister’s office on al-Seka Road.

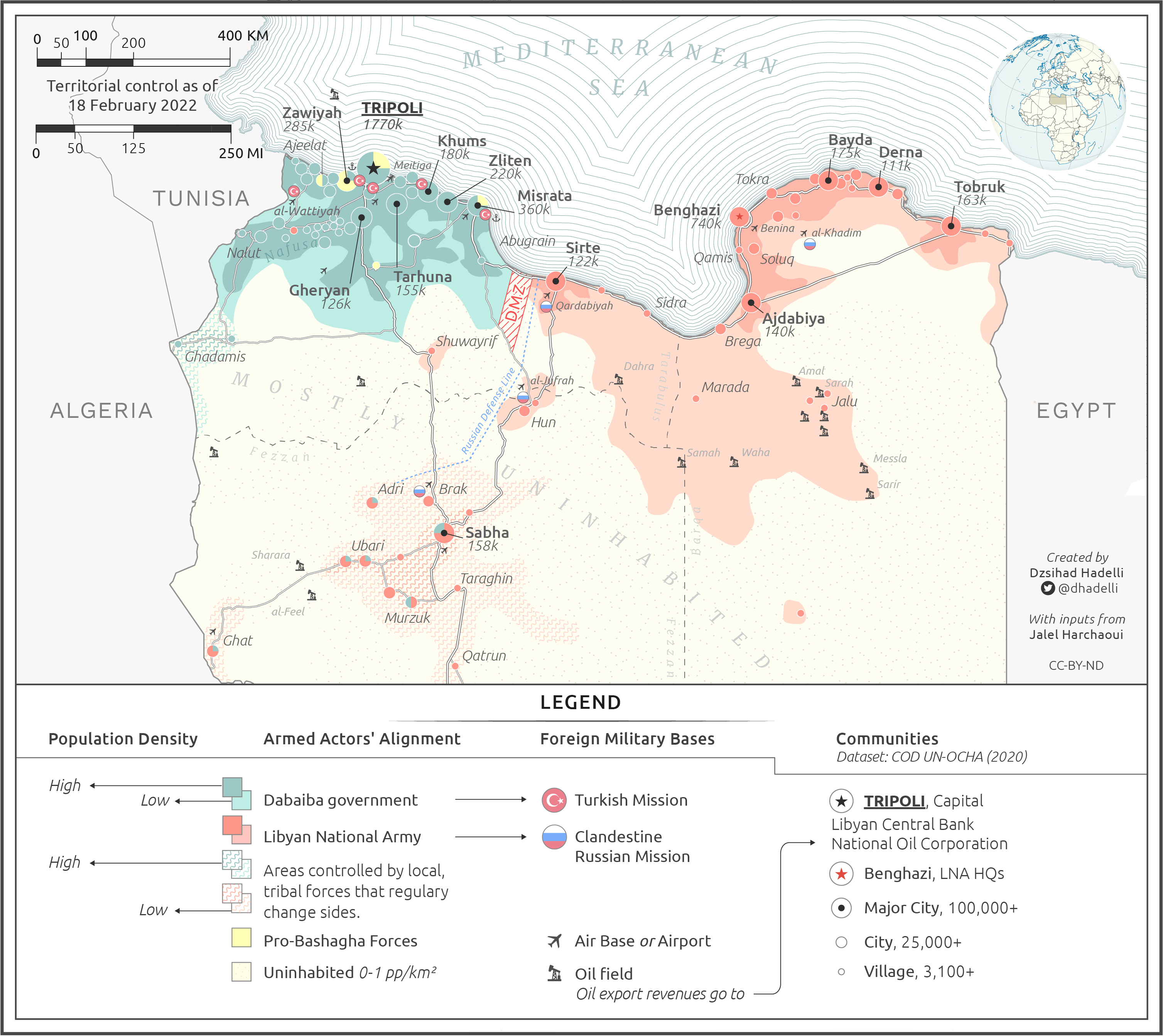

Map by Dzsihad Hadelli.

As part of his plan to dislodge Dabaiba from Tripoli and replace him, Bashagha allied with a string of former foes. He relies on the active political support of Saleh, with whom he has been in partnership since 2020. More recently, the prime minister-designate embraced Haftar and his armed coalition, the so-called Libyan National Army, which dominates most of the country’s eastern half and parts of its southwest. Thirdly, Bashagha also struck an alliance with a loose coalition of armed groups native to Tripoli and its surroundings, dubbed the Stabilization Support Apparatus (SSA). In addition to sharing their hostility toward Dabaiba, Bashagha became attracted to a deal with the SSA because the latter exerts control over strategic territory in and around the capital: the Abu Slim neighborhood on Tripoli’s southern outskirts, most of the city of Zawiyah, and other significant chunks of the greater Tripoli area. This geographic footprint, combined with numerous loyalties inside formal ministries and agencies, makes the SSA the differentiating factor that may help install Bashagha in office this year. Each of these three new allies — Saleh, Haftar, and the SSA — extracted promises and commitments from Bashagha that inevitably will constrict his ability to promote transparency, accountability, and the rule of law.

The unelected Dabaiba — whose U.N.-blessed term began in March 2021 with the understanding that it was to expire at the end of the same year — clung to his top post thanks to the electoral process collapsing in December. He now says he will stay in office until elections are held in June. Having defiantly rejected the House of Representatives’ recent votes, Dabaiba is betting on the United Nations’ potential reluctance to grant its recognition to yet another prime minister without legislative elections having taken place.

Among those who have consistently assisted Dabaiba in consolidating his grip on power month after month, two stand out starkly: Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and Central Bank of Libya governor Sadiq al-Kabir. Dabaiba’s personal rapport with both men traces back to the mid-2000s. Erdogan provides military protection within the scope of the 2019 defense memorandum between Ankara and Tripoli, while Kabir guarantees discretionary access to Libya’s treasury and foreign-exchange reserves. On the ground, Dabaiba presently enjoys the support of an array of armed units: Parts of some of the largest, best-organized brigades from Misrata, and Turkish-backed battalions from suburban Tripoli, stand ready to defend him against any overthrow attempt.

The current map of Libya’s antagonisms is not entirely new. Haftar and his sons, who reign over the east, are still intent on exerting greater sway over Tripoli politics, security institutions, and state coffers. Toward that end, they seek to topple, or at least weaken, whoever happens to be the sitting prime minister in Tripoli — a constant since 2014. Other facets of the Libyan configuration, however, are novel and counterintuitive.

In February 2021, after a violent altercation between Bashagha and the SSA, the United States expressed its support for the then minister of the interior and called the SSA “rogue militias”. A year later, in a crystal-clear illustration of Bashagha’s profound change in attitude, the SSA was the main force providing security for the Misrati politician when he landed at Tripoli’s airport to give his first address as prime minister-designate. As a result of this new alliance, Bashagha no longer speaks of disarming or breaking up any major armed groups like he used to. Instead, he now ambiguously offers to integrate “all the battalions” into the formal ministries, which presages mere cosmetic changes in lieu of any genuine security-sector reform.

The same can be said about Haftar, to whom Bashagha promised the title of supreme commander of all Libyan armed forces as well as friendly ministers in the forthcoming cabinet. Less than two years ago, he accused Haftar of benefiting from the growing illicit trade in Captagon (an amphetamine), stemming from the Levant and flowing through eastern Libya. Similarly, the substantial quantities of cannabis traversing territories controlled by Haftar may benefit his coalition financially. But here, too, because of the recent political alliance, a Bashagha government cannot realistically be expected to go after the bigger criminal networks operating on Haftar’s turf. In sum, whether in the east or the west, a strong Prime Minister Bashagha, capable of presiding over robust law enforcement and security-sector reform, is a doubtful prospect. This reality is hard to face because Bashagha’s reputation in Washington and other Western capitals is that of a leader committed to defending those very principles.

Both Bashagha and Dabaiba follow a philosophy dominated by transactionalism. Both lean heavily on armed groups to advance their agendas. Both have demonstrated contempt for the U.N. roadmap they claim to care about. Both are hell-bent on the prime minister’s office, which they believe they can secure without legislative elections. And both possess close links to the Turkish government.

There are also sharp differences between the two rival politicians. Bashagha is a former air force pilot who, in 2011, fought Qadhafi’s regime, acting as liaison between Misrata’s rebel forces and NATO. He has preserved the indefectible loyalty of some key revolutionary armed groups and influential personalities in his native city as well as in other communities in Tripolitania. In contrast, Dabaiba is by no means a security-oriented leader. Before becoming prime minister, his family was known mainly for the billions that it was suspected to have diverted during decades of managing Qadhafi’s construction projects before turning against the dictator in 2011. Dabaiba, who has dedicated much of his tenure as prime minister to asserting his grasp on all things economic, portrays himself first and foremost as a businessman attached to peace. His demagogic public persona — that of a no-nonsense pragmatist always unselfishly ready to shell out more public funds for the well-being of Libyans — resonated with a large percentage of the citizenry. But this approach requires profligate spending, which is perilously inflationary in nature, just to buoy a popularity that may have already peaked, as Libyan households’ purchasing power is becoming eroded. Still, if the country’s oil carries on pumping and international hydrocarbon markets remain bullish, Dabaiba’s spending policies could prove viable for another year. A Prime Minister Bashagha would be unlikely to work this smoothly with the Central Bank governor, as the two men do not get along. In fact, some Bashagha supporters are already signaling their intention to dismiss Kabir, who cannot be replaced without a long, messy dispute.

What the Current Calm Is Predicated Upon

Libya is not immune from a relapse into civil war. The lull of the last year and a half owes much less to reconciliation amongst Libyans than to an experimental entente between Turkey and Russia. The two dollar-hungry Eurasian powers, after intervening on opposite sides in Libya, have deepened their respective military encroachment while also maintaining a form of calm meant to let the rich North African nation pour billions into infrastructure development and imports. Prime Minister Dabaiba did kick-start a capital-spending revival in 2021, but so far, it has earned Ankara more lucrative contracts in construction, arms, and energy than it has Moscow. As for Cairo, Dabaiba handed it a flurry of idle promises sprinkled with a small handful of actual projects.

Turkey, which has every intention of remaining in Tripolitania, has no appetite for war there. As long as it can maintain its physical entrenchment in northwestern Libya — necessary to carry on deriving geostrategic advantages and economic rewards — Ankara might be prepared to see its semi-hegemony over Tripoli recede slightly. If they can yield a viable equilibrium, minor adjustments could be made toward better accommodating Cairo and other Haftar backers. But while Turkey is keen on normalization, not all western Libyans consider the Turkish presence acceptable.

Turkey Has Libyan Enemies in Tripolitania

Some of the formations belonging to the SSA lost hundreds of their members defending the capital against Haftar’s Emirati- and Russian-backed attack. They were even part of the wider set of militias that received equipment, expertise, and assistance from Turkey when it first came to the rescue of the then-U.N.-recognized Tripoli government.

Irrespective of that recent history, SSA leaders are opposed to the Turkish-backed order that has prevailed in northwestern Libya since Haftar’s main brigades were expelled from the province. From that moment onward, long-standing rivalries over not only ideology but also tangible stakes such as access to public funds via the Central Bank’s tacit benevolence and, crucially, control over illicit activities, have returned to the surface. The juiciest businesses in Libya’s illegal economy these days involve narcotics, fuel, and migrants, as well as inflated service contracts obtained from state institutions.

Since their arrival in 2019, the Turks have shaped key components of northwestern Libya’s security sector, and in so doing, helped elevate not only career professionals but also controversial militiamen. “If the Turks were to leave tomorrow, for whatever reason, a few Libyans on the up-and-up under Dabaiba would certainly be in bad trouble,” noted a Tripoli denizen who fought on Haftar’s side as a volunteer in 2019. Some of the individuals he was alluding to are political Islamists whose stature would have only shrunk had Turkey’s advisors and spies not been around. The itinerary of Mahmud Bin Rajab, who recently was fast-tracked to a senior ranked officer within the Defense Ministry, illustrates well the effects of Turkish meddling.

Bin Rajab belonged to the now-defunct hardline group called the Libyan Revolutionaries Operations’ Room, which engaged in divisive activities, such as the 2013 abduction of then Prime Minister Ali Zeidan. Later, in 2015-2017, during a tribal conflict internal to his hometown of Zawiyah, Bin Rajab took sides once again. His meteoric rise since 2019 thanks to his tight association with Turkey causes some locals to perceive the latter as partisan and disruptive. The SSA, for one, views Bin Rajab and others like him as their Turkish-backed adversaries in the context of Zawiyah’s ongoing crisis and other fractured municipalities.

Other armed groups within the SSA, like the one led by Abd al-Ghani al-Kikli in Abu Slim, simply consider the current Turkish-backed status quo an existential threat. Accordingly, the SSA makes frequent use of the word “homeland” in its public discourse — a nationalistic reference to Turkish interference.

Meet the Stabilization Support Apparatus

In a rare interview mere days ahead of December’s non-elections, a senior SSA leader, Hassan Buzeriba, described the moment on April 5, 2019, when he reneged upon an alliance his clan had previously struck with Haftar. The anecdote was not being offered fortuitously by the Zawiyah armed-group chief, whose thin frame and quiet attentiveness make him at once unassuming and charismatic. It was a reminder that, although made at the last minute by a local actor, the decision to switch sides helped derail the Emirati-backed assault, triggering profound ramifications in the rest of Libya and beyond. The same figures wish to act as kingmakers once again — but throwing their weight the other way this time. “We speak with Saddam Haftar on a daily basis,” added Ali, Hassan’s more talkative brother and a parliamentarian, alluding to tight coordination between the SSA and Haftar’s most active son. “We can’t afford to let Dabaiba stay on as prime minister. Even another three or four months would be out of the question,” he insisted. “The whole world must be aware of the dangerous militants hiding in Turkish-controlled bases, like al-Wattiyah and Sidi Bilal” — a reference to the thousands of Syrian mercenaries discreetly stationed in half a dozen camps across Tripolitania.

The SSA is so amply funded that it went as far as establishing its own maritime force, in addition to having sway in the Libyan Coast Guard. On land, where it has been busy purchasing additional weaponry, it can project power in and around the capital. But despite all these strengths, the SSA — whose logo can be seen splashed in parts of downtown Tripoli and in several other localities in western Libya — doesn’t have the ability to drive Dabaiba out of office unless Misrata’s top brigades and other armed groups presently mobilized in Tripoli give their consent.

The Haftar-Russia Association Isn’t Going Anywhere

Whereas Turkey’s military mission has been largely overt, the Kremlin always denies resorting to hard power in Libya. But this rhetoric should fool no one: The Russian state supports the extensive clandestine Russian mission in Libya. It is in great part thanks to a defense line maintained by thousands of Russian personnel stationed in several air bases and camps that Haftar’s Libyan National Army remains in place in the east and swathes of the southwest. Thus, Haftar and his sons — regardless of their predatory practices, harsh authoritarianism, and inextricable dependency on Moscow — command the only viable security architecture in those vast territories. This helps explain why Haftar and his sons have never experienced any condemnation by the international community. It also explains why anti-Dabaiba actors in western Libya recently allied themselves with Haftar as a way to bolster their own leverage.

But now that Bashagha is in partnership with Haftar, his room for maneuver will be severely curtailed when it comes to confronting, or even discussing, Russian interference in Libya. Dabaiba just last summer had the Ministry of Finance institute a procedure making it impossible for Libyan National Army personnel to receive a salary unless they produce a valid social security number — a way to prevent Libyan public money from reaching the numerous Russians (as well Syrians and Sudanese) on Haftar’s side. This difference in attitude between Dabaiba and Bashagha toward Russia will only deepen with the recent international condemnation of Moscow over its Ukraine policy.

This is not to say that this year’s anti-Dabaiba alliance was a Russian initiative. Its sponsors have been Egypt and France, with Russia playing a supporting role. And Abu Dhabi — although more mindful of Turkey’s preferences — still has a strong organic link both to Haftar in Benghazi and to a heavily armed Tripoli militia leader by the name of Haythem Tajuri, who has worked closely with the SSA since his late-2020 return from Dubai.

What the United States Can Do

At the time of writing, Dabaiba had held onto his seat and Bashagha was still a long way from having won over a majority of the elders, business magnates, and various heavyweights of Misrata. Plus, on Feb. 16, Erdogan articulated his disapproval of Bashagha’s impatience, which indicates that Turkey is not about to abandon Dabaiba just yet. One reason behind the lingering skepticism about Bashagha is the fact that his commitments to Haftar, Saleh, and the SSA leave him little leeway to give solid assurances to those actors’ historical opponents: northwestern Libya’s revolutionaries and their Turkish sponsor. There is even fear in the capital that the prime minister-designate’s negotiation efforts might unknowingly give the Libyan National Army an opportunity to send forces into Tripolitania.

Despite all these topics of concern, a trace of equanimity can be detected in many international diplomats working on Libya: No war is raging, the Islamic State’s presence is containable, and no blockade prevents hydrocarbons from being extracted. Washington exhibited this exact sort of complacency in September when it opted for polite passivity in the face of the faulty electoral “laws” imposed by Saleh with Egyptian, French, and Russian support. A small U.S. diplomatic gesture against the speaker — and other spoilers — during that crucial month could have made a difference and perhaps salvaged December’s elections.

Five months on, optimism is even more misplaced. Whether or not Bashagha’s bet pans out, the deleterious dynamics that it exacerbated cannot easily be dialed down. The support that Bashagha receives at this juncture is circumstantial, which means that most of the anti-Dabaiba forces at play escape his control. Even before Bashagha’s Feb. 10 designation, a dangerous logic of coercion, fait accompli, and threat was on display in Tripoli. On Dec. 21, for instance, armed groups loyal to Dabaiba blocked Mashroue al-Hadhba and other parts of the Abu Slim neighborhood using sand berms and military vehicles in a bid to preempt territorial expansion by SSA forces. Such tensions have only been growing ever since.

Having missed an opportunity in late 2021 with its failure to object to the speaker’s weakening of the elections’ legal framework, Washington should help the Libyan population by increasing pressure on the country’s elites to adopt a sound basis so that legislative elections can happen this year. The United States should also galvanize aspects unrelated to elections such as transitional justice, as well as efforts to denounce criminality and illicit financial flows. In the absence of a firm hand from Washington, Libyan factions will grow more and more tempted to improvise coercive endeavors, such as violent incursions, oil blockades, and deliberate regression from a much-needed banking reunification.

As for the Turco-Russian entente in Libya, its elasticity is finite. Western diplomats should not take it for granted.

Jalel Harchaoui is a researcher specializing in Libya. He is currently preparing an upcoming briefing paper on Salafism for the Security Assessment in North Africa program of the Geneva-based non-governmental organization Small Arms Survey.

Photo by E.U. Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Organization