The Pendulum: How Russia Sways Its Way to More Influence in Libya

Russia has been doing well in Libya — and it likes the fact that few seem to notice it. When describing the relationship between eastern Libyan-based commander Khalifa Haftar and the Kremlin, press articles have been littered with phrases such as “the Russian-backed Libyan general,” “Moscow’s man,” and other verbiage that gives the impression of a straightforward dynamic whereby the Russian state bets and relies on Haftar and therefore focuses on supporting, not undermining, him. Yet a more granular timeline of events reveals a different reality. Since 2014, the United Arab Emirates has been a steadfast, generous, and consequential foreign benefactor for the strongman of Benghazi. In contrast, Russia’s attitude toward him has been complex and ambivalent. The old concept of proxy warfare, whereby a foreign actor chooses indigenous agents as the conduit of its weapons, training and funding, is of little pertinence in the case of Russia’s Libya policy. To increase little by little its sway over Libya’s centers of decision-making, Moscow has followed a less intuitive, more innovative methodology. And it has done so successfully thus far.

It is first important to explore the motivations animating Libya’s three top meddlers, Turkey, the Emirates, and Russia. We can then better understand Moscow’s multifaceted action and shine a spotlight on how the Russian state manages to gain political sway — often irrespective of the conflict’s twists, turns, and reversals.

The Big Three Third Parties

Libya is endowed with a population of only 6.5 million, vast natural resources, an enviable location, and a littoral with immense potential. This helps explain why six to 10 countries interfere in it, as observed by former U.N. Special Envoy Ghassan Salamé. Each one of these foreign meddlers is driven by a unique combination of motivations. The Libyan civil war, which has been ongoing since 2014, experienced two inflection points in recent years. One such defining moment took place in April 2019, when Haftar’s self-styled Libyan National Army, propelled by the United Arab Emirates, attacked the capital, Tripoli, in an attempt to overthrow the U.N.-recognized Government of National Accord. The second watershed event was the January 2020 kickoff of Turkey’s largely overt military intervention against Haftar’s operations in Tripolitania, the country’s northwestern quadrant.

Russia was not instrumental in precipitating either of the two ruptures — but the United Arab Emirates and Turkey were. At the same time, Russia’s pervasive action is impossible to ignore. For this reason, it is necessary to see the Libyan war’s international dimension as involving at least three poles. The seductive idea of a “Turkish-Russian condominium” or “Syrianization” is premature and false since it glosses over the Emirates’ important and uninterrupted interference.

Although not a vital interest for Russia, Libya does attract it for economic and geostrategic reasons. In 2011, Moscow saw the U.S.-led, U.N.-mandated intervention against Moammar Gadhafi’s regime throw in limbo roughly $6.5 billion worth of signed or verbally promised contracts. Having noticed the recent apathy of Western states, Moscow is now determined to revive that chunk of business in the form of infrastructure projects, arms deals, and sales of agricultural goods. It also seeks to exert greater control over the flow of hydrocarbons into southern Europe. On a geostrategic level, entrenchment in Libya helps Russia secure a passageway into sub-Saharan Africa. Lastly, planners in Moscow hardly forget what U.S. Vice President Richard Nixon noted in 1957: Libya occupies a “key strategic position” on the southern flank of NATO. Especially since the Ukrainian crisis of February 2014, the Kremlin perceives the top Western security organization as hostile to Russia’s core interests. For that reason, Moscow seeks to weaken it and positions itself accordingly.

Aspects of Turkey’s agenda in Libya present some similarity to that of Russia. Ankara is interested in recouping all or part of $20 billion of pre-2011 deals that it had with the Gadhafi regime in energy, construction, and engineering. It also sees its growing military presence in the Maghreb country as a stepping-stone for expanding Turkish influence in sub-Saharan Africa. Even more important, Ankara’s maritime ambitions in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea require it to guarantee, mainly by military means, the survival of a pro-Turkey, U.N.-recognized government in Tripoli. Ankara believes that an as-yet-unratified memorandum of understanding signed in 2019 with the Government of National Accord can help justify its expansionism and unlawful activities in the sea until Greece yields and accepts a redrawing of the maritime jurisdiction zones between the two neighbors. For instance, at a more sustained pace in 2020, Turkish seismic survey ships, accompanied by navy frigates, have explored for natural gas in waters close to Greece’s territorial waters. Ankara believes that these waters should be part of Turkey’s own exclusive economic zone. Within that framework, Ankara uses its memorandum with Tripoli as a legitimizing argument.

Unlike the Europeans, Russia has shown a patient willingness to accept and accommodate Turkey’s aspirations to become a full-blown regional power. Ankara and Moscow are often on opposing sides, such as in Syria, Libya, Ukraine, Armenia-Azerbaijan, and other conflicts. Despite this, Moscow makes an effort to remain pragmatic and amenable to talks because Turkey is a convenient partner for Russia to keep. Although a brusque divorce may occur at any time, Moscow has so far valued the option of striking temporary arrangements with Ankara. Those come in handy since they help Russia avoid situations wherein it must wage an intensive, costly conflict over a long period. Another benefit that Moscow derives from preserving its partnership with Ankara is that it contributes to eroding NATO cohesion.

In the eyes of the United Arab Emirates, economic and geostrategic considerations matter, but their top concern about Libya — overriding all others — has been ideology. Indeed, the North African country’s wealth and structural advantages give it a showcase quality: Its fate is closely watched by political constituencies and factions in the rest of the region. If a form of government that grants a degree of influence to political Islam holds onto power in Tripoli in a peaceful context, Abu Dhabi worries that neighboring Sunni-majority countries might be inspired by the Libyan precedent. The Emirati state fears a domino effect across North Africa that could extend to the Arabian Peninsula and ultimately jeopardize its own survival. Because it wishes to prevent this ideational contagion from starting in the first place, the United Arab Emirates is committed to eradicating any mode of governance that may accept or defend the Muslim Brotherhood or a similar faction as a legitimate political strand in Tripoli. An irrevocable corollary from these threat perceptions is that Abu Dhabi will not cease its attempts to make Turkey’s presence in Libya costly, painful, and unsustainable. And yet, although Abu Dhabi knows full well that Moscow regards Ankara as a partner in some circumstances, it has sought “strategic ties” with Russia. Abu Dhabi sees Russian influence in the Arab world as desirable, particularly in light of Moscow’s support for the Bashar Assad government in Syria. This Emirati conundrum has significant ramifications for Libya, where Abu Dhabi always remains tempted to hurt Turkey’s interests, hoping that Moscow will adopt a less conciliatory stance vis-à-vis Ankara. Absent such Emirati activism against Turkey, Moscow and Ankara may work out an arrangement whereby the two Eurasian powers would cohabitate in Libya and share the spoils — an outcome that Abu Dhabi deems unacceptable. Said simply, the Emirates’ Libya policy is absolutist while Moscow and Ankara are both somewhat pragmatic.

In addition to these three states, which are the only ones committed to playing a military role and acting as game changers in Libya, others are involved, such as Egypt, Qatar, Italy, France, Saudi Arabia, and Jordan. In a theater so overcrowded with foreign intruders, it is difficult for a meddler to pursue a coherent strategy at its own preferred pace and without becoming sidetracked into counterproductive detours. Almost every meaningful politician or armed actor in Libya has been courted by more than one external sponsor. That makes Libyan leaders notoriously capricious and hard to dominate as proxies. To maximize its control over locals and minimize its dependence on them, Moscow has built leverage over the years using a sophisticated mixture of tools, ranging from disinformation to diplomacy to banking interference to clandestine military intervention. Lethal equipment deliveries to the Libyan National Army have been linked to Russian entities since late 2014. This happened in part at the instigation of Egypt, which asked Russia to back Haftar’s military campaign. But beyond the military domain, another early boost that Haftar received from Moscow was in the realm of banking.

Financial Interference

Since May 2016, the Russian printing company Goznak has manufactured more than 14 billion dinars’ worth of banknotes (then the equivalent of more than $10 billion) for the Libyan National Army without consulting the country’s internationally recognized central bank. A year and a half earlier, the central bank in Tripoli had cut off its branch in eastern Libya from the nation’s clearing system. But the rogue injections of Russian paper, which enabled Haftar to triple Libyan National Army personnel salaries, bolstered the armed coalition’s independence from the Government of National Accord during the key year that was 2016, and helped keep it afloat. Such Russian activity isn’t purely commercial: Goznak is a state-owned enterprise, which makes it one of the Kremlin’s instruments of leverage over eastern Libya.

The second half of 2020 has witnessed a greater-than-usual scarcity of dinar banknotes in eastern Libya, or Cyrenaica, while indicators point to a likely further worsening of the liquidity crisis in coming months. One cannot attribute this development solely to the firmer manner in which the United States has opposed the Russian deliveries of dinars lately. It also reflects deliberate self-restraint by Moscow at a time when the Russian state is interested in seeing the United Nations succeed in mending Libya’s fractured financial system. Since May 2020, there has been a common desire in both Ankara and Moscow to let diplomacy help reboot the Libyan economy. Moscow slashed the inflow of Russian-printed dinars, even if that has meant putting Haftar in financial straits for several months. Letting the United Nations make headway with its banking-unification process is more important to Moscow because it will eventually enable it to do business in Libya. This is just one among many reminders of how circumstantial Russia’s support for the Libyan commander is. After the country’s financial system is overhauled, Moscow may resume using this tool, and others, to influence and shape the leadership in eastern Libya.

The Wagner Group and Lethal Force

More important than economic statecraft has been Russia’s military intervention, which began in September 2019 and has been carried out mainly through private military companies. Such entities probably debuted in Cyrenaica as early as in 2016, but long stayed confined to a non-combat role. By 2017, the international press was able to establish that the armed men of a Russian company called RSB Group provided security and de-mining services for Haftar’s forces. Russian forces also helped them maintain Soviet-era weapons, including Libyan-piloted warplanes. During the first half of 2018, once the foreign military intelligence agency of Russia’s Armed Forces had conducted a preparatory mission in eastern Libya, the Wagner Group — founded in 2014 by Putin-linked businessman Yevgeny Prigozhin and former intelligence officer Dmitry Utkin — arrived in Haftar’s turf. Initially, Wagner’s role consisted in providing training, hardware, non-kinetic security services, and battlefield advice. A few months after its emergence in eastern Libya, Wagner appeared in Tripolitania. According to a resident of Zintan, a town not far from the capital, Wagner men made it to the then-Haftar-controlled air base called al-Wattiyah nearby in October 2018, a testimony corroborating several European diplomats’ accounts.

In the subsequent month, the connection between Haftar and Prigozhin became plain for the world to see when the two men appeared in a video taken during an official Moscow meeting. The recording shows Chief of the General Staff Gen. Valery Gerasimov in the same frame, an apt metaphor of the link between Prigozhin and the Russian state. While Wagner and its peers are not a branch of the Russian state per se, they are inseparable from it politically, financially, and logistically. The chief executives of these private military companies are part of a wider constellation of oligarchs and moguls linked to the Russian state’s leadership.

Russian private military companies — albeit illegal in Russia — are still managed as businesses. As such, their leaders try to avoid becoming bogged down in a quagmire with no prospect of converging toward an end equilibrium that allows them to capture steady revenue streams in some realistic manner or other. Each adventure undertaken must therefore satisfy objective criteria of economic viability within a time frame of a few years. Although they are on occasion connected to smuggling networks, private military companies like Wagner, through their performance in a given country, can also help a proper Russian corporation, such as an energy giant, secure licit contracts there, and be rewarded for it behind the scenes. While Russian private military companies do deploy clandestine force ruthlessly, including against civilians, they always go to great lengths to make sure they conserve the option of stepping out of the fighting at any time.

The manner in which a given intervention is funded varies wildly depending on the country of operation and the time. A conflict’s particular phase could be financed in one way, and the next in another way, depending on what was negotiated with various partners on an ad hoc, piecemeal basis. For instance, after Austrian financier Jan Marsalek stopped funding RSB Group owing to an embezzlement scandal, the Russian private military company found other means of pursuing its operations in Libya.

Wagner, RSB Group, Shchit, and others employ a diverse array of experienced personnel including former soldiers, retired officers, and military reservists attracted by mercenary salaries. In some cases, those companies, including Wagner, hire individuals with criminal background. But, as Kirill Avramov and Ruslan Trad write in their recent book, Russian private military companies cannot be reduced to financial motivations. They are not entirely driven by short-term profits in the way their Western counterparts can be. Russia’s private security companies are often commanded at various levels by former Spetsnaz (special forces) officers who — beyond greed — are bound by a sense of duty toward the state. Meanwhile, no Russian official will publicly acknowledge any link with these private military companies, regardless of how implausible such denials may sound. To render this cross-breed reality, some scholars speak of “semi-state” security forces. Unlike in Syria, Wagner personnel embody the vast majority of the Russian presence in Libya, with only a small number of regulars on the ground. Russian regulars in Libya are usually technical experts, affiliated trainers, and, sometimes, high-ranking officers responsible for helping Wagner enhance its capabilities. The state’s solicitude reflects the fact that the mercenaries’ action fits within the Kremlin’s broader strategy.

The Beat of Their Own Drum

Shortly after the 2018 Moscow meeting mentioned above, a number of foreign states agreed with the Emirates that Haftar had a clever plan and deserved support. That autumn was propitious for Haftar to prepare his forthcoming advances westward because actors in Tripolitania, as well as the United Nations, were busy trying to consolidate a ceasefire after a month-long battle internal to the province had killed more than 115 and rocked the capital’s fragile balance. It was this moment when the Emirati government gave the Libyan National Army additional material resources so that it could advance into the western half of Libya.

According to a Libyan official privy to a tough meeting between U.S. State Secretary Mike Pompeo and Government of National Accord Prime Minister Fayez al-Serraj in December 2018, the United States was sympathetic to the Libyan National Army as chatter intensified about a forthcoming Haftar offensive. When Libyan National Army forces moved in the oil-rich southwest of Libya, known as the Fezzan, reports suggested that Wagner fighters in northern Cyrenaica stood ready to fly into Tamanhint Airport or other bases in northern Fezzan and assist in securing a giant oil field nearby. That step proved unnecessary in early 2019 — but would happen a year and a half later. Abu Dhabi wasn’t the only capital firmly supportive of Haftar’s adventure in the southwest. “The French were actually more impatient than the Emiratis,” said a Western diplomat who attended the February 2019 summit on Libya. Paris publicly applauded Haftar’s military campaign less than a month before an important U.N.-organized peace conference. Albeit less ostentatiously, Washington, too, was “rather pleased” with it, a U.S. official told me in 2019. After all, apart from uncalled-for brutality against civilians in the Murzuq basin, including potential war crimes, the Libyan National Army, assisted by Sudanese mercenaries, managed to plant its flag in some other key parts of the Fezzan by offering money and peaceful quid pro quos.

The period of late 2018 and early 2019 — which led up to one of the most murderous episodes in Libya’s crisis and also the best opportunity for Wagner to penetrate the oil-rich country much further — shows how the United Arab Emirates’ soft-power reach into Western capitals caused policymakers to forget about the Libyan National Army’s inextricable association with Russia. During those crucial weeks, Moscow itself never shared the West’s enthusiasm for Haftar. Instead, it studied his vulnerabilities with an eye to using them to its own advantage.

When, in March 2019, Haftar withdrew the bulk of his forces from the newly claimed Fezzan to prepare for a march on Tripoli, several actors, foreign and Libyan alike, assumed he’d be able to duplicate in the urban area of 1.2 million people what he had pulled off in the Libyan Sahara — namely, a somewhat elegant takeover with no protracted clashes. But the Kremlin, which wasn’t that sanguine, sat that next phase of the war out. Even before Haftar’s assault began on April 4, 2019, Moscow was of the opinion that the Libyan National Army would likely fail. In fact, both Moscow and Cairo, another meddler in eastern Libya, considered that Haftar lacked the dependability, military might, and socio-political anchoring necessary to succeed in such an outsized undertaking 600 miles from his bases. The skepticism would bring Egypt closer to Russia, but it didn’t stop Haftar, whose top protector is Abu Dhabi.

Little, For Sure — But Not Quite a Sparta

A few days into the April 2019 offensive, the United Arab Emirates, which had long maintained a clandestine military presence in the country, stepped into the battle to offset the Libyan National Army’s frailty on the ground. Between April and December 2019, the Emirates carried out more than 900 airstrikes in the Greater Tripoli area using Chinese-made combat drones and, in some instances, French-made fighter jets. The Emirati military intervention, which also included major logistical assistance and copious arms deliveries, helped keep the Government of National Accord-aligned brigades in check, but wasn’t enough to propel Haftar’s men into downtown Tripoli. Mere weeks after Abu Dhabi started its bombing campaign, Ankara followed suit by sending its own drones and several dozen Turkish personnel, who carried out about 250 strikes in 2019. It is important to acknowledge that, before January 2020, the Emirati intervention in Libya was dramatically larger than the Turkish one. And still, that failed to suffice.

Ideologically, Turkey and the Emirates have been mortal enemies since the 2013 military coup in Egypt. But developments in Libya in 2019 were the first instance where personnel from both states were involved militarily in the same war theater. That Turkey possessed its own indigenously developed drones gave it valuable agility at a small cost while facing off indirectly against the Gulf state. But the main obstacle encountered by Abu Dhabi in western Libya was not equipment related, as its air campaign that year was much more relentless than Ankara’s. The problem was the Libyan National Army’s inadequate manpower. “Haftar can’t control a city of 3 million with just 1,000 men,” summarized Italian Foreign Minister Luigi Di Maio. Although hyperbolic and sarcastic, the Rome official’s quip highlights what has been the Achilles’ heel in the Emirates’ approach to Libya: Not enough young Libyans have been willing to risk their lives as foot soldiers on the frontline for Haftar.

After Sudanese autocrat Omar Bashir fell from power in 2019, many speculated that his successors would let their notorious Rapid Support Forces fight for the Libyan commander — but that never materialized. This explains why the vast majority of the few thousand Sudanese fighters who have been acting as pro-Haftar mercenaries on Libyan soil consist of Darfuri rebels, usually less disciplined than the Rapid Support Forces. Something similar can be said of the Syrian government, as almost all of the approximately 2,000 Syrian mercenaries fighting alongside Haftar are “reconciled rebels,” considered expendable and ineffectual compared to the more battle-hardened armed forces that Damascus still needs at home.

This acute difficulty in finding infantry for Haftar must be borne in mind by anyone interested in understanding the nature of the relationship between the United Arab Emirates and Wagner. Abu Dhabi keeps working closely with Moscow not because it shares its vision or because it trusts the Kremlin, but because it has no alternative.

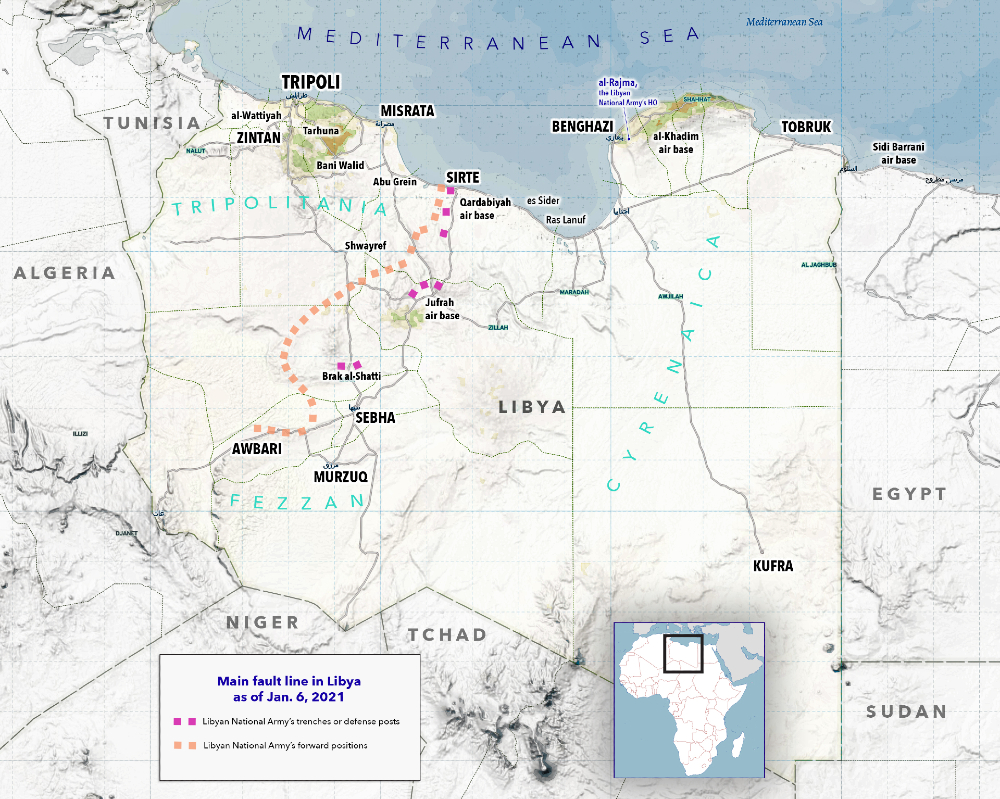

Figure 1: Fault Lines in Libya

Source: Generated by the author.

By late August 2019, the Libyan National Army’s offensive on Tripoli had not merely become bogged down in a stalemate — it was in jeopardy. In September 2019, Russian fighters joined the Libyan National Army brigades on the outskirts of Tripoli and participated in the offensive on the Libyan government. Wagner’s engagement, although it began with the loss of up to three dozen of its men, would persist and grow for several months. The Russian contingent acted as a force multiplier for Haftar’s offensive and made it more “fearsome,” said a Government of National Accord-aligned fighter interviewed. Wagner forces provided a deadly resilience across the Libyan National Army’s vanguard, which had formerly been lacking. The addition of tighter coordination, anti-drone capability, expert snipers, and advanced equipment allowed the Libyan National Army to make small yet consistent advances into the capital’s suburbs. Thus, over the autumn of 2019, Russian fighters became an essential component of Haftar’s operation.

In mid-May 2020, as per a pattern familiar to watchers of Syria’s Idlib area, the two capitals chose to avoid prolonging a war-fighting episode deemed unnecessary and with no end in sight. The offensive on Tripoli, not having ever been a Russian project, was essentially discarded without consulting Haftar. In exchange, Ankara and Tripoli committed to letting Russian personnel exit the Greater Tripoli area safely. Other topics of negotiations such as the possible release of two Russian spies arrested by the Government of National Accord a year prior were put back on the table, said a Libyan official familiar with the conversations. Meanwhile, Wagner’s exit from Tripolitania would let it concentrate on better defending the territories outside of Turkey’s sphere of influence.

On May 22, Turkey instituted a drone-strike moratorium and Russian mercenaries withdrew at once from northwestern Libya. In broad daylight, hundreds of Wagner personnel left southern Tripoli and Tarhuna, Haftar’s forward operating base in the west. “The Wagner mercenaries came by the main road, and flocked to our airport,” said a Bani Walid resident interviewed by phone, echoing another eyewitness. Bani Walid is a partly neutral town situated in the eastern part of Tripolitania. “The Russians were more than 2,000 in total. Some of them went straight through to Jufrah air base without even stopping. The situation was tense in our city.” The rough estimate comports with the figure of 3,000 Russian fighters published later by U.S. Africa Command Center. According to a third Libyan source, Wagner’s abrupt withdrawal made it impossible for Libyan National Army or Sudanese units to smooth out the transition, hence their inability to avoid Haftar’s drastic collapse in Tripolitania. Less than two weeks after Wagner withdrew, Libyan National Army forces and their non-Russian mercenaries had no choice but to abandon vast quantities of equipment and flee the province.

This back-and-forth — between ferocious fighting against Turkish-backed Libyan forces and a more passive stance — is the crux of the Kremlin’s approach. First, Russia doesn’t share the Emirates’ commitment to propping up Haftar under all circumstances. Second, the United Arab Emirates’ policy in Libya features security gaps. For more than half a decade, Moscow has been the only actor both able and willing to fill those gaps. As Russia does so, it becomes more essential to Haftar’s architecture and then uses that status to tilt the conflict according to its political will, which differs from that of the United Arab Emirates. The exit from the Tripoli area showed the Kremlin’s willingness to hurt Haftar and Abu Dhabi’s agenda in situations where such moves let Moscow extract incremental advantages via its dialogue with Ankara and Tripoli.

Politics by Other Means

Since the Turkish-backed Government of National Accord forces, with the help of several thousand Syrian mercenaries, expelled Haftar’s armed coalition from northwestern Libya in June 2020, the territorial divide between the two main camps has been static. The fault line runs from the city of Sirte, located in the middle of Libya’s littoral, down to the strategic Jufrah air base 160 miles farther south. In a much less clear manner, another line going from Jufrah air base to Awbari, 300 miles to the southwest, runs between the Fezzan and the northwestern part of the country. The reluctance of Turkish-backed Government of National Accord forces to attempt further advances since June was achieved through continued work by Wagner.

Both Moscow and Abu Dhabi carried on sending lethal equipment. Wagner has made a significant contribution along the Sirte-Jufrah frontline by planting hundreds of anti-personnel and anti-car mines, digging trenches, and building defense posts that feature air defense systems manned by well-trained Russian personnel. Rumors about suspected S-300 systems near the oil port of Ras Lanuf even sparked fears of “anti-access/area denial” zones taking shape in North Africa until U.S. Africa Command Center issued a soft denial. This situation is ironic given that the United Arab Emirates sent an MIM-104 Patriot air defense system to Libya in January 2020, only to give in to American pressure and remove it from the war theater, a European defense attaché and other Western sources said in interviews.

Wagner has also been active along the Jufrah-Awbari line, expanding its light footprint into the Fezzan. As part of these efforts to dissuade Turkish-backed forces from venturing into the east or the south, Moscow even introduced 14 MiG-29 fighter jets and Su-24 bombers piloted by mercenaries. The deployment of these Russian warplanes, which elicited some anger from the United States, helped even out the balance of power between Libya’s two main camps. On Nov. 2, U.S. Ambassador to Libya Richard Norland visited Moscow, a preview of how Russia’s discreet persistence in the North African country may, over time, become accepted as a force to reckon with.

The fact that those quiet advances are made by a private military company in lieu of the Russian state itself makes them more difficult to address or stop. Over the last 12 months, the Wagner Group has greatly increased its command-and-control activities in several military bases across Libya. In an August 2020 interview, a senior insider to the U.N. peace talks on Libya recognized that “the Russians” now controlled Qardabiyah air base, a large dual-use airport located 15 kilometers from the coastal city Sirte, and made similar comments about Jufrah air base, another strategic facility situated farther south. “If a demilitarization of that overall area is agreed, the Russians won’t leave Jufrah Airbase right away. But hopefully they’ll leave later on,” he added, betraying an awkward ambiguity often detected in diplomats when it comes to Wagner’s growing military presence in Libya. But Western military officers tend to be more candid. “There is no sign the Russians are retrograding or preparing to depart from Libya,” Rear Adm. Heidi Berg, director of intelligence for U.S. Africa Command Center, told me last month. “To the contrary, it seems that they seek to become even more entrenched.”

In addition to Jufrah and Qardabiyah — two air bases that are now run almost entirely by Wagner — a third one called al-Khadim, near Benghazi, has also hosted substantial Russian activity this year. Initially, the United Arab Emirates refurbished al-Khadim air base in 2016. For several years, Emirati-contracted cargo planes landed frequently at the facility. Through most of 2019, Emirati forces operated both Jufrah and al-Khadim, until they moved most of their combat drones and personnel to facilities in western Egypt, letting Wagner settle into the two Libyan bases in their stead. In early spring of 2020, al-Khadim became a major point of entry for Russian logistical support according to open-source data analyzed by aircraft-tracking specialists. By some estimates, Russian Air Force flights from Syria into eastern Libya averaged about one cargo plane per day for several months. The manner in which these valuable bases moved from Emirati to Russian hands is a tangible example among others of de facto coordination between Moscow and Abu Dhabi.

Cuts Both Ways

Deterring the Government of National Accord-aligned armed groups is not the only purpose of Wagner’s security apparatus. The Russian presence also acts as a potential means of coercion against Haftar or anyone else aspiring to lead the eastern Libyan factions. A telling illustration is the failed coup attempted by Haftar last spring in eastern Libya, his own fief.

Weeks before experiencing the above-described series of military trouncings in northwestern Libya, the 76-year-old field marshal suffered a political setback in Cyrenaica. On April 27, Haftar appeared on TV and declared his intention to form a new government under his authority and have the Tobruk-based parliament submit to the Libyan National Army. The very next day, Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs Sergey Lavrov aired Moscow’s disapproval of Haftar’s remarks about political power being transferred to his army. Such a public rebuke coming from Russia on a domestic issue would have been unthinkable six or 12 months prior. What is even more noteworthy is the fact that Moscow prevailed: Cairo agreed with Moscow’s preference and both capitals prevented Haftar from dissolving the existing civilian government of eastern Libya. Also, Aguilah Saleh, the head of the eastern-based parliament, did not submit to the Army General Command like Haftar wanted. Instead, the head of parliament has remained active, including on the diplomatic front, despite — or, rather, thanks to — his slight divergence from the Libyan National Army boss. To underscore the preference, Lavrov referred to Saleh several times as Moscow’s direct interlocutor while making almost no mention of the field marshal since April.

In the summer, the Kremlin showed once again its wariness of Haftar by negotiating a first step toward a potential stabilization of the Libyan conflict without including the warlord. Ahead of Aug. 21’s tentative ceasefire proposals from both Saleh and Government of National Accord Prime Minister al-Serraj, Russia held diplomatic negotiations with both Turkey and Egypt but shunted the Libyan National Army altogether. For that reason, the latter initially dismissed the Aug. 21 declarations. On at least five occasions, Haftar’s forces stationed at the frontline near Sirte fired salvos of Grad-type rockets toward Government of National Accord forward positions around Abu Grein, a town to the south of the prominent anti-Haftar city of Misrata. The Russian fighters in Sirte stayed away from Haftar’s attempts to break the ceasefire, which ended up holding.

The August 2020 incidents serve as a reminder that the Libyan National Army’s General Command has no control over the Russian forces. Over the course of the year, Wagner has significantly increased its influence on the ground, including inside or near important oil facilities. While the Russian forces’ strength grew, the Emirati mission in Libya lavished two Libyan National Army units — the Sudanese-heavy 128th Brigade and the Salafist-dominated Tariq bin Ziyad Battalion — with top-of-the-line equipment funneled through the General Command. According to a U.N. source, Abu Dhabi speaks directly to some senior Sudanese mercenaries in Haftar’s camp, and provides them with logistical support in a bid to bolster the Libyan field marshal. But none of this puts a dent into the Russian forces’ autonomy.

In late summer, U.S. diplomatic pressure was a major factor pushing Haftar to lift an Emirati-backed $10 billion oil blockade that he imposed at the beginning of 2020. But Wagner’s presence at Libyan oil installations such as Ras Lanuf and es-Sider also played a role in bringing about the end of the blockade. In mid-September, when Russia invited Haftar’s son and heir apparent Khaled along with the Government of National Accord’s deputy prime minister, Ahmed Maetiq, to convene a resumption of oil exports, the field marshal was in bad need of visibility. By agreeing to let oil exports resume, he seized an opportunity to appear powerful once again — even as he relinquished crucial leverage, knowing that reinstating the blockade may prove more difficult than in early 2020.

After more than two months of negotiations, the U.N.-backed Political Dialogue Forum hasn’t managed to create a brand-new government of national unity, but it showed Saleh as still holding a small chance of being installed at the helm of the country’s Presidential Council, while no formal role was truly contemplated for Khalifa Haftar. This is not to say that Moscow is attached to Saleh. Rather, it has been using him, and other figures, to eclipse Haftar slowly, without hurting the field marshal frontally. Another effect of Russia’s influence was the presence of Gadhafi loyalists among the delegates chosen by the United Nations, a notable difference when compared to the format of 2015’s U.N.-backed talks in Skhirat, Morocco. A cornerstone in Russia’s thinking about Libya is its firm intention to bring back politicians, technocrats, and security officials known for their loyalty to the late Moammar Gadhafi, another point of agreement between Cairo and Moscow. Among numerous other maneuvers, Moscow invited a delegation of Gadhafists led by Cairo-based figure Khaled al-Khoweildi in April 2019, and reportedly, even established indirect contact with Moammar Gadhafi’s son Saif al-Islam. A turn to Gadhafist networks is a means of counterbalancing the Haftar family’s highly personalized brand of rule in eastern Libya, without strengthening the pro-Turkey factions in the west.

Conclusion

The Russian state, despite having the capacity to do so, never made the strategic decision to engage head-on in a long bout of war and ensure that Haftar triumphs in western Libya. Instead, Moscow has been working quietly to render the field marshal less and less indispensable to its agenda in eastern Libya — but gradually, without ever clashing with him. The Kremlin wishes to see a less unpredictable, less dysfunctional class of Libyan elites run Cyrenaica. It would use that to secure more perennial access to key facilities there, such as, potentially, a naval base, more hydrocarbons concessions, and the option to do business with Tripoli.

The Kremlin moves slowly and surreptitiously closer to that objective by exploiting the weaknesses of the United Arab Emirates’ Libya policy. Despite Moscow’s pragmatic attitude vis-à-vis Turkey, Abu Dhabi and its proxies have no choice but to keep working with Wagner. By fulfilling a military role in eastern and southwestern Libya, Wagner acquires essential importance there. The Kremlin then converts this into sheer power in those Libyan territories, which currently fall outside of Turkey’s sphere of influence.

As for the Turkish-backed authorities, Moscow has managed to preserve a communication channel with them even though Wagner continues to be a dangerous threat. “If we have to give a bit of business to the Russians to get them off our back, that can be envisaged,” said a member of the Government of National Accord in a June 2020 interview. The admission is a euphemism given the distinct possibility that Tripoli may have to award large contracts to Russian companies within the next year or two.

Since its 2013 rise as a major counter-revolutionary interferer across swathes of the Middle East and Africa, Abu Dhabi has become renowned for its single-mindedness. Moscow views that trait as a given — not as a phenomenon it must combat, appease, or rectify. As with many other dysfunctional dynamics characterizing the region, the United Arab Emirates’ stubborn absolutism offers rewards for actors nimble enough to work around it, or even exploit it tactically.

Indeed, the two anti-liberal powers disagree on fundamental points, a particularly salient one being whether Turkish influence should be allowed to exist in Libya. But as things stand today, the Emirati-backed camp there is too weak to be able to even hinder Turkish expansionism without Russian military assistance. For that reason, the United Arab Emirates has no choice but to work and coordinate with Wagner. In fact, Abu Dhabi has likely funded parts of Wagner’s operations, as U.S. Africa Command Center noted in a recent report. Wagner’s indispensability in turn strengthens the Kremlin, whose own goals do not include the total eradication of Turkish influence from Tripoli. Abu Dhabi, however, cannot settle for anything less.

Cognizant of the discrepancy between Little Sparta’s exigencies and vulnerabilities in Libya, Russia has implemented a new modus operandi by combining skillful soft-power maneuvering with the use of force through an unacknowledged semi-state actor. This low-cost strategy has enabled Moscow to become an impossible-to-circumvent power broker in a country where it had lost all sway in the wake of the U.S.-led intervention in 2011. In all cases, the war is not over — and the Russian pendulum is not done swinging in Libya. Time is on its side.

Jalel Harchaoui is a senior fellow specializing in Libya at the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, a Swiss-based institute. He previously was a research fellow at The Hague’s Clingendael Institute, where he is grateful to have had the opportunity to work on parts of this essay.