In Post-American Central Asia, Russia and China are Tightening Their Grip

Although America’s war in Central Asia may be ending, worries over potential conflict in the region remain high. On Oct. 1, following a war of words between Tajikistan’s government and the Taliban, the Russian foreign ministry raised concerns “about the growing tension in Tajik-Afghan relations against the background of the mutually acrimonious statements by the leaders of both countries.” In the wake of ongoing uncertainty about Afghanistan’s future, the Russian-led Collective Security Treaty Organization is planning an unprecedented four exercises on the Tajik-Afghan border in October, all simulating an armed incursion.

States in Central Asia bordering this area are increasingly leaning on external partners to shore up their defenses. As the United States exits the region, Russia and China are ramping up their security assistance. Still, current trends do not point toward a great-power competition in the region between these two nations.

Just days after the Taliban marched into Kabul, Russia held two military exercises with Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. The second, larger exercise took place only 20 kilometers from the Afghan border and involved 2,500 Russian, Tajik, and Uzbek troops, as well as tanks, armored personnel carriers, attack jets, helicopters, and other weaponry in a simulated joint response to cross-border militant attack.

China is also enhancing its security presence. A few days after the Russian exercise concluded, China’s powerful Ministry of Public Security held counter-terrorism drills with its Tajik counterparts. China’s strategic activity in Tajikistan has grown significantly since it opened a small military facility in the country near the border with Afghanistan in 2016. It even undertook drills with the Ministry of Public Security — the first international training activities it had ever conducted.

Afghanistan, and China’s fixation on the idea of Uyghur militants returning from Central Asia to set up camps, has driven an unprecedented level of Chinese security activities in neighboring states. In 2014, General Secretary Xi Jinping made a number of secret speeches in the bordering Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, since leaked to the New York Times, in which he expressed concern that “Uyghur fighters” could use Tajik territory as a transit zone to staging attacks in China. However, there is no evidence of Uyghur militants operating out of Tajikistan. In fact, recent International Criminal Court filings suggest the country’s Uyghur population has dramatically plummeted following in-country raids on Tajik territory by Chinese security services, targeting civilians in bazaars across the country.

China and Russia are bound by several interests in Central Asia. Both share a concern about the region becoming a source of terrorism. Both want to contain any instability that may emanate from Afghanistan. And both want to push the United States out of the region. This last goal has been realized, but neither Russia nor China can really take the credit for it.

Goodbye, America

With the U.S. troop withdrawal from Afghanistan, Washington’s already limited role in the region looks set to diminish further. Prospects of a return of U.S. troops after the withdrawal were met with limited interest from Central Asian governments.

In the immediate aftermath of 9/11, as the United States launched operations in Afghanistan, it used Central Asia as a logistics hub, opening bases in Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan. By 2014, both bases were closed. And the Northern Distribution Network, a series of supply lines to Afghanistan via Russia and Central Asia launched in 2009, was shuttered in 2015 following rising tensions between Washington and Moscow.

Although the U.S. government pledged to build new facilities on Tajikistan’s border with Afghanistan, security assistance has dropped from a high of $450 million a decade ago to just $11 million in 2020. The United States and NATO collectively account for 85 of the 269 joint exercises involving Central Asian militaries since 1991, according to data collected by The Oxus Society for Central Asian Affairs. But their frequency has also declined from a peak of seven in 2003 to an average of just two since 2018, with no recent drills in the wake of the collapse of the Afghan government.

Russia Entrenched

Russia remains the region’s main security partner. It maintains military facilities in Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan, supplies half of Central Asia’s arms imports, and has organized 121 joint exercises since independence. Russia has a range of mechanisms to provide security, both bilateral and multilateral, such as the Commonwealth of Independent States and the Collective Security Treaty Organization.

Our data demonstrates that while Russia’s share of the regional arms market for the past decade has remained consistent, it has steadily increased its share of regional exercises from 39 to 49 percent as the region geared up for the withdrawal from Afghanistan. Central Asian states have agreements with Russia to buy weapons at reduced rates. For the region’s poorer states, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, Russia often simply donates arms, most recently giving 12 BRDM-2M patrol vehicles to Tajikistan in mid-September. Russia’s exercises are, on average, twice the size of those run by their nearest competitor, China. And unlike China, which has focused on developing ties with Central Asian security services and police forces, Russia focuses on military-to-military cooperation. Two-thirds of Russian-led joint exercises have involved the Russian army or air force. This dampens the potential for cooperation with Beijing.

Russia has also demonstrated its hard power capabilities in the region in recent years. In August 2018, Russian forces in Tajikistan launched a series of airstrikes against drug traffickers, marking its first armed intervention in Afghan politics since the Soviet withdrawal in 1989. A few weeks after the fall of Kabul, Russia strengthened its 7,000-strong 201st Military Base in Tajikistan with 30 new tanks, 17 new BMP-2M infantry fighting vehicles, and a batch of Kornet anti-tank guided missiles.

Since the ascendance of the Taliban, Russia has been testing its logistics networks to transport Mi-8 and Mi-24 helicopters to Gissar Air Base outside Dushanbe in case of a destabilization in Afghanistan. Rapid reaction capabilities have been enhanced to strengthen the Tajik border, with Russia transferring Su-25 attack aircraft from Kyrgyzstan to Gissar as well. Unlike competitors such as China, Russia maintains regional prestige thanks to its combat experience in Syria, which allows it to train using tested tactics and techniques.

China Marches West

At the same time, China’s role in the region has been growing, with its share of the arms market increasing from 1.5 to 13 percent over the past decade. China is also establishing a strategic foothold in areas where Russia is lagging technologically, such as with drones. China has sold its CH-3, CH-4, CH-5, and Wing Loong drones to partners such as Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. China has also been more active in terms of strategic drills and has organized 35 joint exercises either bilaterally or through the Shanghai Cooperation Organization.

China began to take a more active role in the defense of Central Asia in 2014, seeing it as a bulwark to prevent instability in Afghanistan from spilling into Xinjiang. These domestically oriented goals have led Beijing primarily to focus on integrating its internal security services, paramilitary forces, and counter-terrorism forces with those of neighboring states.

Some 59 percent of Chinese exercises we have tracked involve the security services, with special operations forces and police units not far behind. This exhibits a marked difference from the Russian approach to regional security. The Chinese exercises include Cooperation-2019, a series of drills allowing China to enhance the interoperability of local paramilitary units with the Communist Party’s armed wing, the People’s Armed Police. Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan each took part, marking the first time their national guard units had trained with their Chinese counterparts regarding counter-terrorism.

The security-focused nature of these drills also reveals China’s desire to continue placating Russia, which sees itself as the dominant security actor in the region. Beijing has shown deference to Moscow here in the past. In 2017, the Development Research Center — an influential think tank under China’s cabinet — invited high-profile Russian researchers to a private seminar to ascertain Moscow’s red lines in the region. Recent drills even suggest deepening cooperation. In 2021, for example, the Sibu/Interaction exercise, which was the largest to ever be held in China with Russian forces, involved greater emphasis on joint actions, including command and control, than previous exercises.

China’s Growing Influence

At present, Russia and China do not appear to be competing in Central Asia. But this will be tested as China’s rise in the region continues during the early post-American era. China may not be eating into Russia’s share of the arms market at present, but it may start to do so as China’s domestic arms industry develops and continues to seek export markets.

Although China has largely been deferential to Russia and is likely to remain so in the near term, there are signs that it is considering its own approach to this strategic part of the world. Increasingly, China has developed its own initiatives without Russia. It organized its first exercise outside of the auspices of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization in 2014, and established its own multilateral mechanisms such as the China+Central Asia meeting of foreign ministers, launched in 2020, and the counter-terrorism with Pakistan, Tajikistan, and Afghanistan, established in 2016.

As China’s economic and security interests continue to grow in the region, the current Sino-Russian framework of cooperation may be folded within a broader Pax Sinica in which Beijing increasingly calls the shots.

Bradley Jardine is a global fellow at the Wilson Center’s Kissinger Institute on China and the United States.

Edward Lemon is a research assistant professor at the Bush School of Government and Public Service.

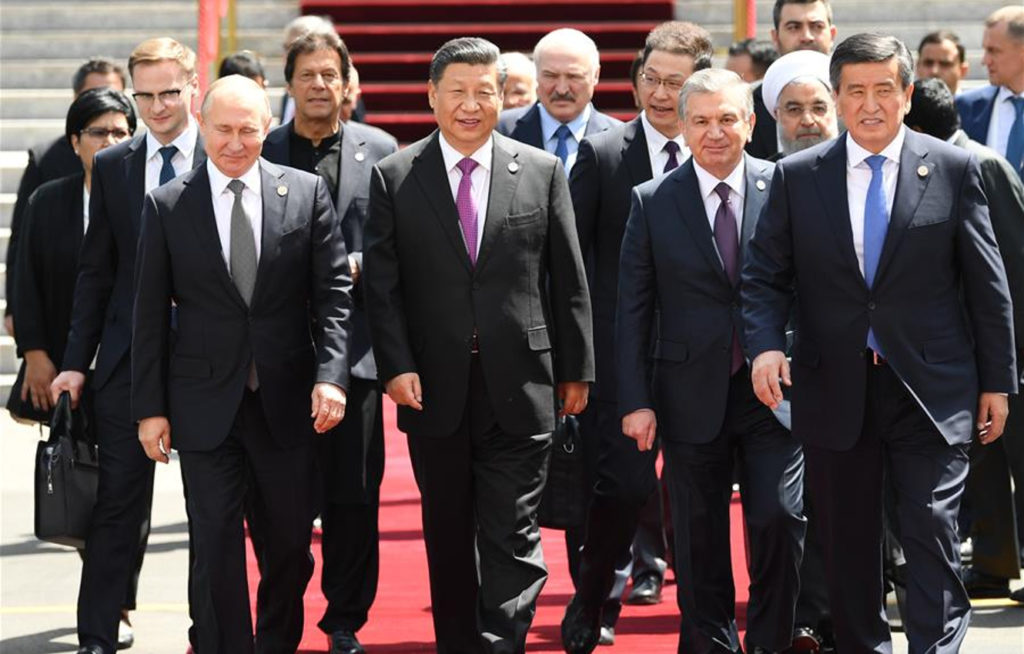

Image: Xinhua (Photo by Yin Bogu)