The Evolving Geography of the U.S. Defense Industrial Base

Rosie the Riveter worked in California. One of more than 310,000 women who toiled in the U.S. aircraft industry in 1943, she became emblematic of a defense industrial base that expanded massively to meet the demands of World War II.

Figure 1: We Can Do It! By J. Howard Miller

Source: J. Howard Miller, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons. Accounts differ on which of the thousands of aircraft workers active in the 1940s was the inspiration for the iconic Rosie the Riveter poster. The most credible claim is that she was Naomi Parker Fraley, an employee of the Naval Air Station in Alameda, California.

For decades following that conflict, California was the center of gravity for the U.S. aviation industry. Historic company names like Lockheed, Northrop, Hughes, and others trace their lineage to the Golden State. But, although California remains integral to America’s aviation industry today — and to the defense sector overall — America’s defense industrial landscape has changed significantly since World War II and the Cold War.

In recent years, the geography of U.S. defense spending has been undergoing a subtle shift. That has been driven by a mix of major programmatic trends, changes in Department of Defense acquisition organizations, and broader technology requirements. Other regions are gradually eclipsing areas of the country that have long been central suppliers of materiel to the Pentagon.

Overall, defense contracts have grown more concentrated among fewer locations in the United States. Understanding where the U.S. defense industry is primarily located today offers indications of its connection to broader commercial sectors, whether they be in aviation, information technology, or other areas. The increased concentration of defense technologies and companies in geographic “clusters” could also exacerbate an already troubling divide between the U.S. military and the broader civilian population. Additionally, the changing landscape of the defense industry has implications for congressional oversight, as members of the legislative branch seek, or avoid, roles on key defense committees.

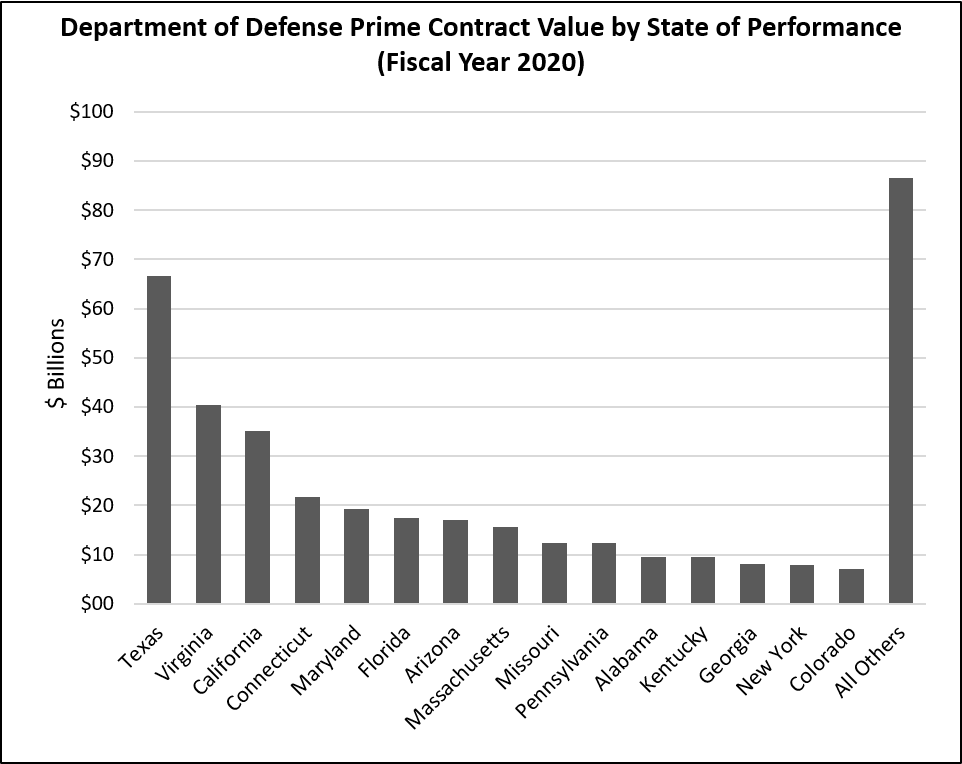

The Concentration of U.S. Defense Industrial Capacity

The American defense industrial base is quite concentrated, at least at the prime contractor level. Over three-quarters of the value of Pentagon prime contracts awarded within the United States go to firms in just 15 states. And that concentration is growing: According to Defense Department data, between Fiscal Year 2012 and FY2020, the share of total defense contract value executed in these 15 states grew from 74.8 percent to 77.6 percent. (And the share of total defense contract value executed in the top 10 states grew from 62.5 percent to 66.7 percent.)

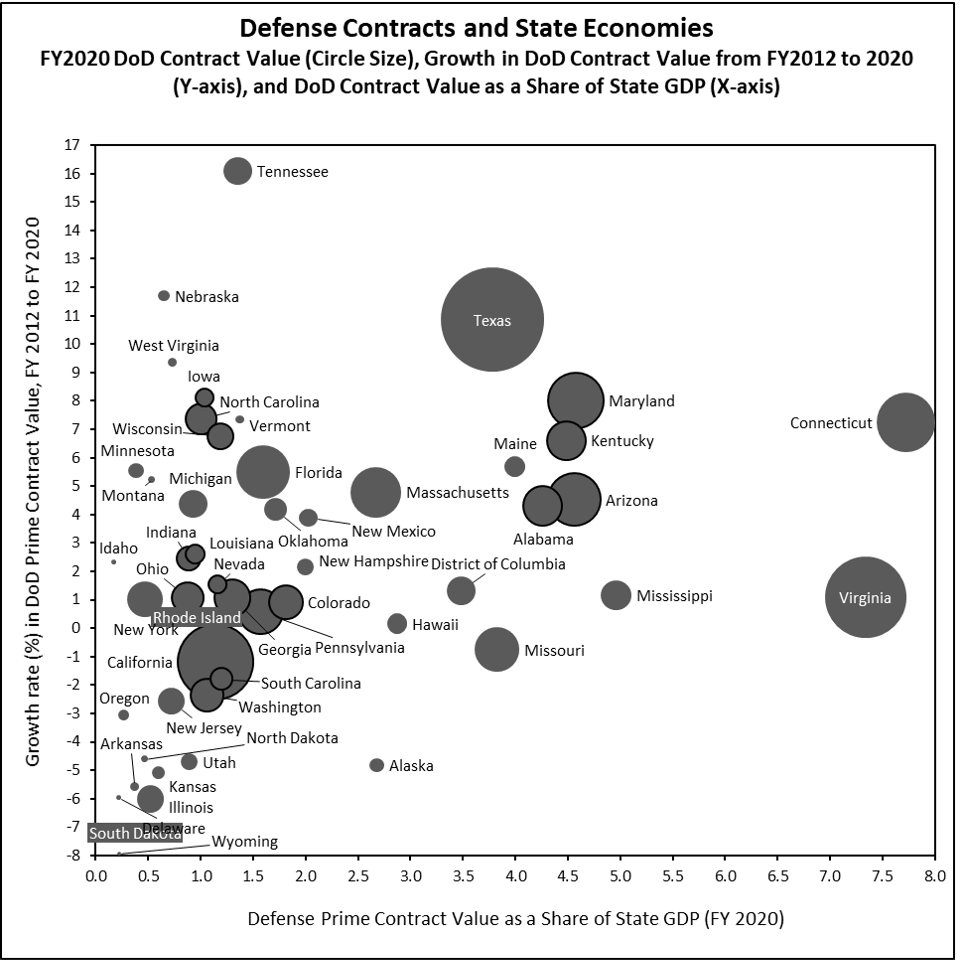

Figure 2

Source: Generated by author, based on Avascent analysis of Federal Procurement Data Service (FPDS) contracts data. Throughout this article, references to contract values from U.S. government FY2012 through FY2020 are drawn from both FPDS data and from the Department of Defense Office of Local Defense Community Cooperation (“Defense Spending by States – Fiscal Year 2019”).

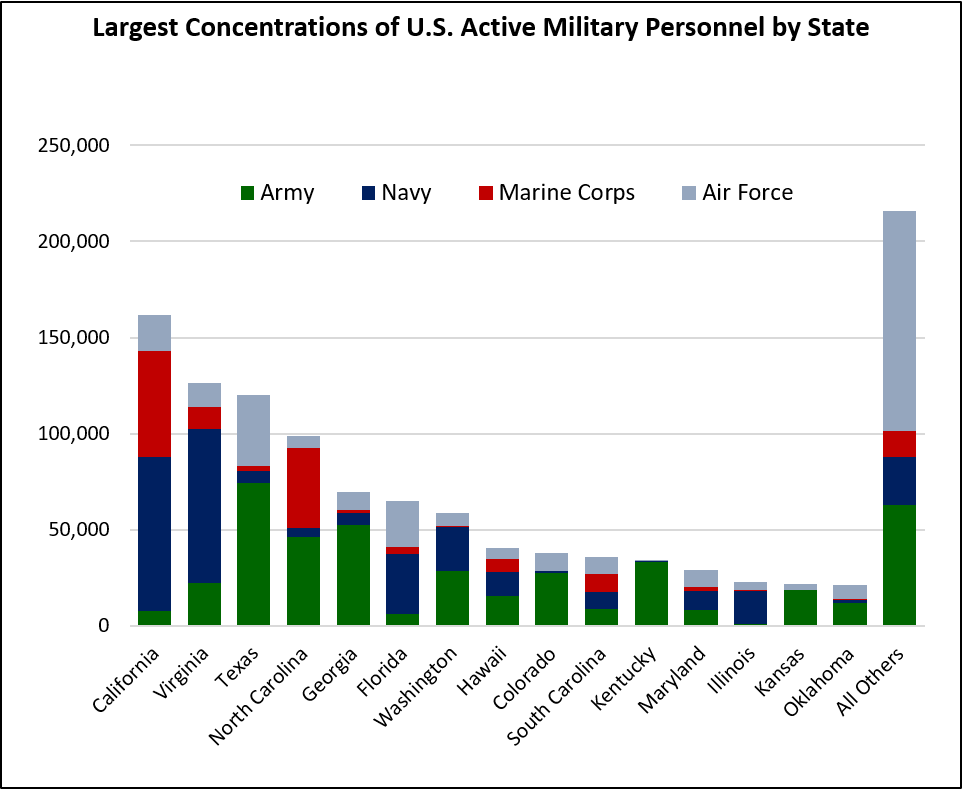

Multiple factors drive the distribution of Defense Department prime contract dollars across the country. One of these is the geographic footprint of U.S. military facilities and personnel. Even facilities that play no role in acquisition exert strong influence on the geographic flow of Pentagon contract dollars. The same 15 states that account for such a large share of contract dollars also house over 60 percent of active military forces stationed inside the United States and nearly 60 percent of all Pentagon civilian employees who are not based overseas. States like California, Florida, Texas, and Virginia, for example, have long been home to tens of thousands of active-duty military personnel, who depend on support services and supplies provided by local firms.

Figure 3

Source: Generated by author, based on data from Defense Manpower Data Center, March 2021. Space Force personnel are included in Air Force figures. Large concentrations of U.S. Air Force personnel are also based in New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, and Alaska, among others. Large numbers of U.S. Army personnel are also based in New York state and Alaska, among others. Figures do not include U.S. military personnel based overseas (e.g., Germany, Japan, Kuwait, South Korea, etc.).

The geographic distribution of the Pentagon’s contract dollars is also heavily influenced by the evolution of the department’s technology demands, the rise of new centers of acquisition authority, and the mix of programs and contracts the Pentagon’s suppliers execute. Factors like these have produced an evolution in the geography of U.S. defense spending in recent years.

Technology Priorities, Organizational Change, and Geographic Impact

Growth in spending on new technology priorities has especially benefitted Maryland and Alabama. Among all states, these two rank fifth and 11th, respectively, in terms of Defense Department prime contract dollars awarded to local companies (and other entities, like universities). This is particularly noteworthy as neither state is among the top 10 states in terms of the number of active-duty military personnel stationed in them. Maryland ranks 12th and Alabama ranks 25th.

Maryland is home to several entities that drive a lot of defense contract spending, including the Naval Air Systems Command, as well as the corporate headquarters of Lockheed Martin. But it is Fort Meade, home of Cyber Command and the National Security Agency, that has “put Maryland on the map” as a major destination for Pentagon and intelligence community dollars. The Defense Department budgeted an estimated $10.2 billion in FY2020 for cyber capabilities. A significant amount of this money pays for the capabilities developed, acquired, and operated at and around Fort Meade.

Maryland is also home to Aberdeen Proving Ground, which has grown in recent years because it attracted many functions the Army moved from Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, which closed in 2011. Aberdeen Proving Ground gained roughly 8,500 new positions following that round of base realignment and closure: Many of the activities shifted to the installation are related to command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (C4ISR) equipment, helping to cement the position of the Old Line State as a center of such activities. Not surprisingly, the share of the state’s gross domestic product from defense contracts grew from 3.1 percent in FY2012 to 4.6 percent in FY2020. (This calculation, like others provided in this article for different states, draws on data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis.)

In the case of Alabama, the expansion of the Huntsville area as a center of government acquisition of space, missile, and missile defense capabilities has accelerated. Huntsville and nearby Redstone Arsenal have been associated with rocket technology since the mid-1940s. NASA’s Marshall Flight Center was established near Huntsville in 1960 to capitalize on the area’s rocket expertise. Successive decisions by various Defense Department components to base more and more acquisition and technology functions there have led contractors (e.g., Boeing, Northrop Grumman, SAIC, Leidos/Dynetics, and Lockheed Martin) to locate substantial engineering and other capacity in the area.

Alabama may yet grow its role in military space activities even further. In January 2021, the Defense Department announced that Space Command would move from its current home at Petersen Air Force Base in Colorado Springs to Redstone Arsenal. The move would concentrate space operations and space technology in a single location. (The Government Accounting Office, however, is reviewing the Pentagon decision.)

Alabama is also home to other defense-related industry, but some of those activities have seen contractions in recent years. For example, Austal, based in Mobile, has seen the Littoral Combat Ship program wind down. Nevertheless, growth in Pentagon spending on contracts executed in Alabama meant that defense accounted for over 5 percent of the state’s annual gross domestic product in FY2020, up from just 3.7 percent in 2012.

Alabama, like many states with a heavy defense presence, has benefitted from strong advocacy in Congress for the state’s defense and civil space industry. Among the notable representatives of the state, Sen. Richard Shelby currently serves as the ranking member on the Senate Appropriations Committee, having been chairman of the panel from April 2018 through January 2021.

The Rise (and Decline) of Major Programs of Record

The ebb and flow of major programs can drive meaningful change in where Pentagon dollars are flowing. Two examples illustrate the impact that Defense Department acquisition spending can have in making some states and local areas major players in defense.

Texas and the F-35 Lightning

Texas draws the largest amount of defense spending of any state in the union by a wide margin. (See Figure 5.) This is driven in part by large concentrations of military facilities, such as Fort Hood, Fort Bliss, Lackland Air Force Base, Randolph Air Force Base, and many others. In total, Texas is home to nearly 122,000 active-duty military personnel and more than 48,000 Pentagon civilian employees. Only Virginia and California are home to larger numbers of Defense Department personnel. Like those two states, Texas boasts a very substantial defense industrial presence. Lockheed Martin, Raytheon Technologies, Boeing, Textron, L3Harris, General Dynamics, and many other firms have operations in the Lone Star State.

Among the systems built in Texas is the F-35. The Joint Strike Fighter is easily the largest Defense Department acquisition program in terms of budget. In FY2020, the F-35 accounted for $12.2 billion in combined procurement and research, development, test, and evaluation (RDT&E) funds.

The growth of the F-35 program has helped to expand defense spending in Texas. In FY2012, the Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps collectively ordered 31 F-35 variants. By FY2020, they had increased production to 96 jets. Investment spending on the F-35 over this period grew by more than 36 percent. It is, therefore, no surprise that total defense contract dollars going to prime contractors in Texas increased by nearly 11 percent over the same period. Although defense prime contract dollars grew as a share of the Texas economy over this period, they still only account for 3.8 percent of the state’s economy, given its breadth and diversity.

Missouri and the F/A-18E/F Super Hornet

If the Joint Strike Fighter shows how a growing program can boost the role of defense spending in a state’s economy, the Super Hornet illustrates the opposite. Between FY2012 and FY2020, the value of prime defense contracts flowing to firms in Missouri declined by 0.8 percent. As a share of the state’s economy, defense contracts dropped from 4.9 percent in 2012 to 3.8 percent in 2020.

No company has bigger defense operations in Missouri than the Boeing Company, which undertakes a number of activities in the state, including final assembly of the F/A-18 in St. Louis. The F/A-18 franchise, comprising production of the F/A-18E/F Super Hornet and the EA-18G Growler variant, and upgrades of these and earlier variants, experienced a funding decline of about 15.8 percent between FY2012 and FY2020. This included a decline in the number of new airframes ordered, from 40 to 24. In its FY22 budget request, the Navy planned no further orders of Super Hornet aircraft.

Diverging Trends in States’ Reliance on Defense Spending

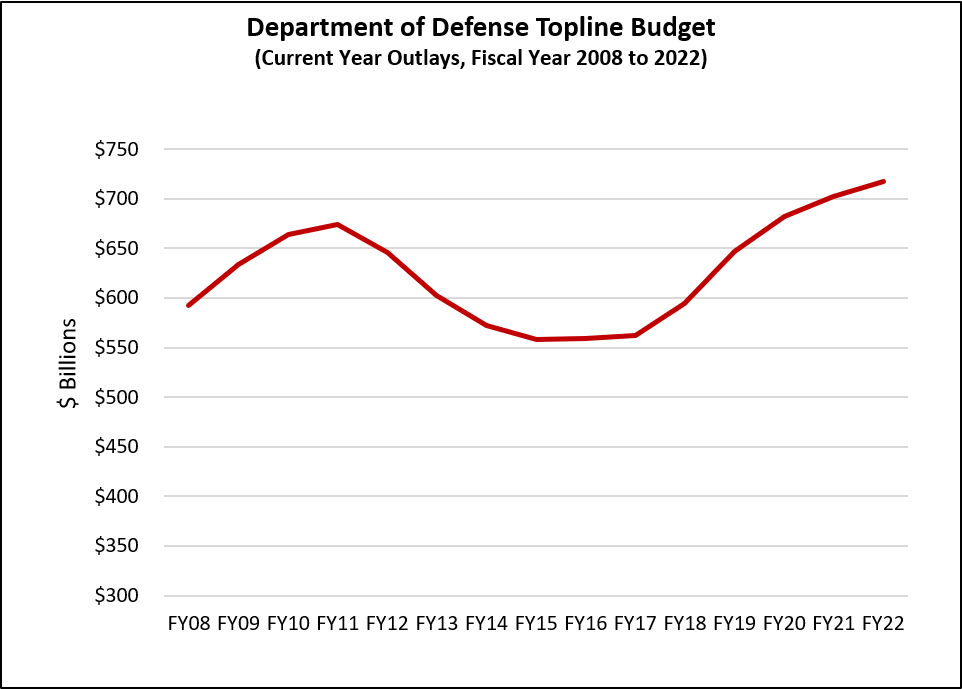

While defense spending has grown significantly from its most recent low point in 2015 (see Figure 4), the geographic distribution of that growth has varied widely. Defense technology spending is becoming more critical to some regions of the country and less so to others: California and Connecticut, respectively, exemplify these diverging trends.

Figure 4

Source: Generated by author, based on data from the Office of Management and Budget, FY22 President’s Budget. Figures are shown in outlays. FY2015 represented the most recent low point in the cyclical ebb and flow of the Defense Department budget, influenced both by the wind-down of operations in Iraq and Afghanistan and the impact of discretionary spending caps imposed by the 2011 Budget Control Act.

In addition to having the largest number of active-duty military personnel of any state, California is home to key Pentagon acquisition agencies, like Naval Information Warfare Systems Command in San Diego and Space Systems Command in Los Angeles. As with Huntsville in Alabama and Fort Meade and Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland, these locations are surrounded by a significant presence of defense contractors. Beyond these, California’s Edwards Air Force Base and companies in nearby Palmdale remain critical to advanced U.S. military aviation.

Figure 5

Source: Generated by author, based on contracting data taken from the Federal Procurement Data Service (FPDS) contracts data and Department of Defense Office of Local Community Cooperation (“Defense Spending by State – Fiscal Year 2019”). State gross domestic product data taken from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, U.S. Department of Commerce. The size of the circle represents the value of FY2020 defense contracts by state, the X-axis represents the value of defense prime contracts as a percentage of each state’s economy, and the Y-axis represents the compound annual growth rate of defense contracts flowing to each state between FY2012 and FY2020.

But, while the aviation industry continues to draw on Californian companies, defense as a whole plays a declining role in the state’s highly diverse economy. The volume of prime contracts going to firms based in California declined by 1.2 percent between FY2012 and 2020. (This trend might moderate in the coming years, as the B-21 bomber, assembled by Northrop Grumman in Palmdale, enters production.) Defense prime contracts in FY2020 accounted for just 1.1 percent of California’s gross domestic product, down from 1.8 percent in 2012. This is despite the Pentagon’s push since the mid-2010s to tap into that other giant of the Californian economy, Silicon Valley. For example, contractors in California have received more “other transaction authority” contracts, which the Defense Department is increasingly using to attract commercial technology providers, than firms from any other state.

By contrast, Connecticut has seen its reliance on Defense Department contracts continue to grow. Connecticut is home to iconic brands like Sikorsky (owned by Lockheed Martin), Pratt & Whitney (owned by Raytheon Technologies), and Electric Boat (owned by General Dynamics), as well as the Navy’s submarine base in New London. About 7.7 percent of Connecticut’s economy in 2020 was driven by defense prime contracts, the highest share of any state. The value of defense prime contracts going to Connecticut companies grew faster than 7 percent between FY2012 and FY2020, driven by multiple aviation and submarine programs. The elevation of Rep. Rosa DeLauro in 2021 to the position of chair of the House Appropriations Committee will help to ensure a continuation of that trend.

Prospects for Continuing Change and Why It Matters

The shape of the defense economy does not evolve rapidly. Major programs tend to last a long time, with design modifications offering a new lease on life for many facilities. Ongoing sustainment activities and the manufacturing of spares also continue even after the production of platforms or other major systems ends. Further, neither the Department of Defense nor Congress seems eager to undertake a new round of politically wrenching base closures. This means that defense facilities with either operational or acquisition roles will likely stay as they are for the time being.

But subtle shifts in the geography of the defense industrial base are likely to continue. Some states, such as Georgia, could see further declines in the flow of defense spending to them. For Georgia, the value of prime contracts performed in the state declined by about 0.3 percent since FY2012. Looking ahead, while Georgia is home to Lockheed Martin’s C-130J facility in Marietta, production of that aircraft is unlikely to continue indefinitely. Further, the Air Force’s planned retirement of the E-8C JSTARS aircraft, based at Warner-Robins Air Force Base, may not be followed by a successor aircraft at all as the service examines its approach to the Advanced Battle Management System.

Similarly, Washington state, which has already seen defense contracts decline by 2.4 percent since FY2012, could experience a further reduction in its share of defense dollars as the Navy ends production of the Boeing P-8A Poseidon. This comes as Boeing also moves to diversify its commercial aircraft production footprint beyond its historic Pacific Northwest home by housing its 787 aircraft line in South Carolina. That shift may partly offset a modest decline (of 1.2 percent) that the Palmetto State saw in defense contracts between FY2012 and FY2020.

Another major trend will have important implications. No sector or skillset will be as critical to U.S. national security in the years ahead as software development, engineering, and integration. Software represents a rapidly rising share of the value of defense platforms. Areas of critical priority for the Pentagon, like artificial intelligence, machine learning, cyber, advanced networking, and Joint All Domain Command and Control will hinge on the work of talented software engineers.

To develop software, the Pentagon and the intelligence community will increasingly find themselves drawing on the capabilities and capacity of the commercial marketplace. The career website Zippia indicates that the five areas best suited for software engineers are Washington state, California, Oregon, New York state, and the District of Columbia. While this may be an imperfect measure of where software engineering capacity is located, it indicates that the marketplace for software development is increasingly located in major urban areas that are home to commercial enterprises, higher educational institutions, and venture capital. In 2018, the Army acknowledged this when it announced that the new Army Futures Command would be established in Austin “to better partner with academia, industry, and innovators in the private sector.” Similarly, the Pentagon created the Defense Innovation Unit in 2015, with offices in Silicon Valley, Boston, and Austin, to get closer to commercial sources of innovation.

Of course, software engineers can work from nearly anywhere. Although working from home on classified projects presents real challenges, the Pentagon needs to find a way to accommodate this trend. Doing so will be critical for the Defense Department’s ability to access a larger share of the nation’s productive capacity.

More generally, the Pentagon has a potential strategic imperative to connect with a broader array of Americans, fewer and fewer of whom have served in the military. At a time when commercial technologies and non-traditional suppliers are increasingly vital to maintain U.S. military technical primacy, the Department of Defense has had a harder time attracting new entrants to the defense supply base. The increasing concentration of the U.S. defense industrial base thus appears to be both a symptom of a broader trend — the isolation of the Defense Department from broader American society — and a critical source of risk: If the established defense industrial base grows more concentrated in fewer areas, then accessing the kinds of commercial technologies, processes, and business models that will be needed in the coming era of great-power competition could grow more challenging.

Doug Berenson is a managing director at Avascent, a global consulting firm serving clients in government-driven markets like defense, aerospace, and cyber. Doug has been with the firm for over 20 years, helping government and corporate clients forecast trends in demand, weigh investment options, and make effective policy decisions.