Tarhuna, Mass Graves, and Libya’s Internationalized Civil War

Last month, forces aligned with Libya’s internationally recognized government made a gruesome discovery within the vicinity of Tarhuna, some 50 miles southeast of the capital, Tripoli. As many as 230 corpses were dug up from unmarked sites or found buried in bulldozed pits behind villas. A handful had been thrown in a well. Several dozen more piled up in a hospital morgue. Many of these bodies were bound and showed evidence of torture. Not all of them were captured fighters: Some of them were civilians, including women and children as young as three.

While much international commentary has rightly focused on the human-rights implications of the Tarhuna atrocities and calls for accountability, the mass graves are illustrative of some of Libya’s least-discussed factional dynamics. The town had long been under the control of the Kaniyat, a brutal militia that aligned with eastern-based commander Khalifa Haftar in April 2019 amid his high-profile attack on the U.N.-backed Government of National Accord in Tripoli. For more than a year, thanks to the Kaniyat’s iron fist, Tarhuna served as Haftar’s bridgehead in western Libya. The Government of National Accord’s takeover of the town on June 5 was a devastating blow to the rebel commander’s ambitions. But the Kaniyat’s barbaric style of governance has implications much broader than mere battlefield intrigues. The situation in Tarhuna reveals the dangerous absurdity and consequences of imposing a simplistic narrative on Libya’s complex local politics.

I began researching this issue while in Tripoli, Misrata, and other localities nearby last summer. At the time, roads from the littoral into Tarhuna were still open, but the war made it too hazardous to try and visit. I still managed to discuss the town’s politics and recent past with an array of Libyans, pro- and anti-Haftar alike, both from Tarhuna and otherwise.

The sinuous and violent rise of the Kaniyat over the last decade has received little attention. Now that their legacy is in the news, their story must be faced. Its forbidding complexity embodies an important truth about Libya’s nine-year conflict: It cannot and should not be summarized. The country’s violence has no overall thrust. It is mercurial and often obeys ultra-local dynamics.

Tarhuna and other cities surrounding Tripoli. (Map by Jalel Harchaoui)

Tarhuna, a modest rural municipality with a population of 40,000, was known during the Muammar Qadhafi era for producing military officers for the government’s security apparatus. For that reason, a large proportion of its inhabitants came out the political losers of the 2011 uprising that toppled Qadhafi. Tarhuna hosts more than 60 tribes, though allegiances are not wholly determined by tribal lineation, but also by political beliefs, money, and opportunism. Cohesion is felt more strongly within a family or a small clan. In some cases, even that has its limits.

Haftar has roots in Tarhuna through his father’s side. After he returned from exile to Benghazi in mid-March 2011 and helped topple his old boss, Tarhuna was one of the few places in western Libya where Haftar found support. That hospitality faded in June 2012, when Tarhuna’s security chief Col. Abu Ajila al-Habshi, a friend of Haftar’s, was abducted. Several of the Tarhuna natives I interviewed, suspect that a combination of Tripoli and Misrata militias disappeared him. Civilian revolutionaries saw Habshi, like many other army officers who had fought Qadhafi in 2011, as a threat.

Kani Brothers Give Rise to the ‘Kaniyat’

Habshi’s kidnapping also rendered Tarhuna more susceptible to the rise of informal armed groups of militiamen with no professional training. The first such groups to assert themselves in Tarhuna were the Na’aaja clan, the town’s most fervent proponents of the 2011 revolution. A group dominated by Na’aaja individuals assassinated a young Tarhuni called Ali al-Kani in a grisly manner. This was revenge: Amidst the anarchy of 2011, Ali al-Kani and his brothers had killed a dozen members of the Na’aaja clan. They simply took advantage of the greater conflict to settle old scores, a Tarhuna native told me. Of the seven Kani brothers, only Ali had revolted against Qadhafi in 2011, albeit belatedly. Following the regime’s fall, the Kani family became renowned for its criminal activities, not its military strength. But after Ali’s 2012 murder, his surviving brothers responded by exterminating entire Na’aaja families, demolishing their homes, and chasing many others out of town. The massive reprisals kicked off the slow transformation of the “Kaniyat” into the local power to be reckoned with.

In those years, the main fault-line tearing Libyans apart was between those who sought to preserve chunks of the old order and those committed to upturning every bit of it. In contrast to the large cities of Tripolitania, a majority of Tarhuna’s population remained loyal to Qadhafi’s memory. That characteristic made the community a danger to Tripolitania’s new elites. Yet, driven by calculation, not ideological sympathy, the Kaniyat cultivated a rapport with the most virulently anti-Qadhafi actors, including tough political Islamists and Misrata’s hardline revolutionaries. Misrata is a powerful merchant city of 350,000 located east of Tripoli. The Kaniyat attracted the support of those revisionist currents by marketing themselves as the only brigade ruthless enough to “contain” their town and its surroundings.

As a new civil war erupted in May 2014, the Kani brothers threw their lot against Haftar’s Operation Karama, which sought to defeat all Islamists in Benghazi and overthrow the rump government in Tripoli. The Kanis instead pledged allegiance to the Fajr Libya coalition forged by Misratan and Islamist factions. Within that context, the Kani brothers intensified their ferocious war on the Na’aaja clan. In March 2015, they murdered several members of Habshi’s family, including the former security chief’s daughter, blaming them for favoring Haftar’s camp.

Other than such moves, designed to entrench their supremacy locally, the brigade did little in the way of fighting alongside the Misratans in Tripoli. The Fajr-versus-Karama conflict cooled off in the spring of 2015. By year’s end, the Kaniyat had absorbed the local military and police, morphing into a mini-army of about 4,000 men in control of the Tarhuna area. Although ambivalent and Machiavellian, the militia remained close to anti-Haftar elements. For instance, in May 2017, when militias native to Tripoli expelled anti-Haftar figure and former Libyan Islamic Fighting Group commander Khaled al-Sharif, his affinity with the Kani brothers enabled him to find refuge in Tarhuna before escaping to Turkey via Misrata.

The Militia’s Moneymakers

Their fearsome reputation, along with the occasional execution of entire families, enabled the Kani brothers to impose security and quiet. That turned them into social leaders of sorts, with almost a sense of economic accountability toward the populous Tarhuna area’s communities at large. The Kaniyat generated revenue streams independently from the state and declared their own local “ministries.” In territories they controlled — which briefly even included Garabulli (a segment of the shoreline between Misrata and Tripoli) — they collected taxes from factories, catering companies, and cleaning services. The militia was involved in garbage collection and owned several clinics and businesses in the Nawahi al-Arbae area between Tarhuna and southern Tripoli. They also raised funds by collecting traffic fines. But the Kani empire’s core income was derived by levying a tax on all human and fuel smuggling traversing its territories.

Yet Mohammed al-Kani, the leader of the family, deemed these revenues insufficient. Moreover, from 2015 to 2019, all revolutionary factions across Tripolitania became weaker, sidelined by more centrist and pragmatic currents. In 2017, the Kani family funded and ran a counter-smuggling unit, using the Central Security Forces of the GNA’s Interior Ministry as a front. Although paradoxical coming from an armed group profiting from smuggling, many such actors in northwest Libya, including the Kaniyat, adopted an anti-crime narrative specifically to gain socio-political legitimacy. The Kaniyat even invoked religious rhetoric borrowed from purist Salafism.

Notwithstanding that change of tactic, Tarhuna grew more isolated politically and its economic prospects deteriorated. The Tripoli government saw no upside in favoring the pastoral town other than conceding a few meaningless pleasantries to it, such as the hollow promise to build an international airport there. During that same period, Tripoli’s own militias such as the Tripoli Revolutionaries Battalion and the Radaa Force acquired more sway and wealth. The ever-widening economic chasm between the capital and several cities in its vicinity (including Tarhuna) caused armed groups from the periphery to contemplate attacking the capital.

A Flawed Attack on Tripoli

Solidarity — or the illusion of it — amongst outlying communities against the capital deepened in May 2018, when the Kaniyat signed a peace deal with both Misrata and its old enemy, the mountain city of Zintan. Three months later, feeling the pinch of their economic travails, the Kaniyat acted upon the temptation to attack. The resulting assault was dubbed “the letter-of-credit war” in reference to a banking embezzlement technique popular amongst central-Tripoli militias. The latter were so corrupt, the Kaniyat’s narrative went, that only violence could ameliorate the problem.

A successful incursion would have enabled the Kani family to dislodge militia leader Abd al-Ghani “Ghniwa” al-Kikli from his southern Tripoli turf and take ownership of his illicit money schemes. But the endeavor failed to elicit the anticipated support from Zintan or Misrata, other than the participation of hardliner Salah Badi and his Sumud Battalion. Several other more moderate militias from Misrata came near Tripoli’s eastern flank but stopped short from joining the attack.

The Misratans ended up converting their military threat into political influence: Fathi Bashagha became the new minister of the interior in October 2018. A Libyan air force pilot turned businessman, Bashagha portrayed himself as a rebel in 2011 by acting as a liaison with Western special operations forces during the siege of his home city Misrata. Belying his reputation as a leading Misrata moderate, he was among the hawks who pushed for the Fajr war effort of July 2014, meant to expel Haftar’s Zintani allies from the capital. Bashagha then broke from his city’s more hardline elements. His critics allege this was simple political opportunism. In late spring 2015, Bashagha helped bring about a withdrawal of Misrata’s brigades from the edges of a large air base in western Libya controlled by Haftar’s allies. The conciliatory gesture ushered in a long period during which Misrata’s moderates stuck to a more accommodating stance toward the U.N. peace process that led to the formation of the Government of National Accord in 2016.

In 2018, much to the chagrin of the Kaniyat, Bashagha and other Misrata moderates stayed out of the war. The four-week assault by the Kaniyat and Salah Badi on Tripoli’s militias, after causing more than 100 deaths, yielded a resounding defeat for the actors that initiated it. The Kani family lost its access to the coast and other valuable territories. Unlike Misrata’s Badi, the brothers avoided international sanctions by signing the U.N.-backed ceasefire agreement. The Government of National Accord promised Tarhuna several dozen million dinars, which it never paid out. Calm returned, but no genuine peace emerged between the Kaniyat and Tripoli: This agreement couldn’t last long.

Haftar, who’d already sketched out a rapprochement with tribal leaders of Tarhuna, refrained from criticizing the Kaniyat during the month-long battle. The marshal recognized the potency of the Kaniyat’s “struggle against corruption” narrative. This, along with the tactic of attacking Tripoli from the south via the International Airport, was a key source of inspiration for the Emirati-backed Haftar..

In January 2019, the Kaniyat moved on the International Airport again. The main forces that repelled them belonged to Usama al-Juwaili, an anti-Haftar leader from Zintan. Juwaili managed to convince Hamzah Ashwia, the head of a Zintani unit called Battalion 19 on Tarhuna’s side months earlier, to switch and join him. Ashwia’s inside knowledge of the Kaniyat’s tactics would later prove key.

Haftar Makes a Deal with the Kaniyat

The Tripoli militias blamed the latest airport attack on Bashagha, accusing the newly appointed interior minister of appeasing the Kaniyat. The internecine bickering encouraged the capital’s numerous enemies. Tripoli was so divided, it appeared easy to conquer. For years, Haftar’s top goal has been to overthrow the Tripoli government and rule over Libya. As for Tarhuna’s Mohammed al-Kani, he was impatient for recognition and prestige, desperate for cash, bitter towards both Tripoli’s and Misrata’s forces, and determined to restore his honor. Haftar turned the Kani brothers into a military ally by giving them money and weapons. The Kaniyat adopted a brand-new name — the 9th Brigade. Pro-Haftar media outlets would soon refer to the 9th Brigade as a regular component of the Libyan National Army, not a mere “Haftar proxy.”

Haftar struck a similar deal in the city of Gharyan, 40 miles southwest of Tarhuna. Using money and promises, he rallied Adel Da’ab, a militia leader known for his human-smuggling activities. In 2014, Da’ab was allied with Haftar’s foes, but by 2017 felt neglected by them. The Libyan National Army now had access to two strategic territories: Gharyan and Tarhuna. Haftar’s men snuck into these territories and used them as a launchpad for their march into Tripoli’s southern outskirts on April 4, 2019. Three days later, the Kaniyat joined Haftar’s war effort in southern Tripoli. As weeks went by, the Kaniyat’s contribution became more substantial. The overall lack of progress was worrisome: The takeover of the capital was not supposed to last more than a few days. Using unguided rockets, Tarhuna’s militia participated in the Libyan National Army’s shelling of Mitiga Airport, Suq al-Jumaa and other suburbs, indiscriminate operations that killed hundreds of civilians.

When Haftar lost the city of Gharyan to the Government of National Accord in June 2019, Tarhuna became even more central to Haftar’s pursuit of his war against the Tripoli-based government. Amid the headlong rush, Mohammed al-Kani now began killing potential dissidents and their families at the slightest suspicion of disloyalty. After all, few of his advisers, administrators, and right-hand men were true Haftar believers. Gharyan had fallen to the Tripoli government partly thanks to the activism of some of its own habitants. The Kanis dreaded a similar scenario in Tarhuna.

Mohammed al-Kani’s younger brother Mohsen, dedicated to military matters, tended to disregard Haftar’s day-to-day instructions, while receiving logistical support from the marshal. Meanwhile, Misrata’s moderates offered large sums of money in return for a non-aggression pact, to no avail. On Sept. 13, 2019, Mohsen was killed along with other key armed leaders of Tarhuna. The pro-GNA militia the Radaa Force claimed responsibility for the slayings, but the Libyan National Army may have been behind them.

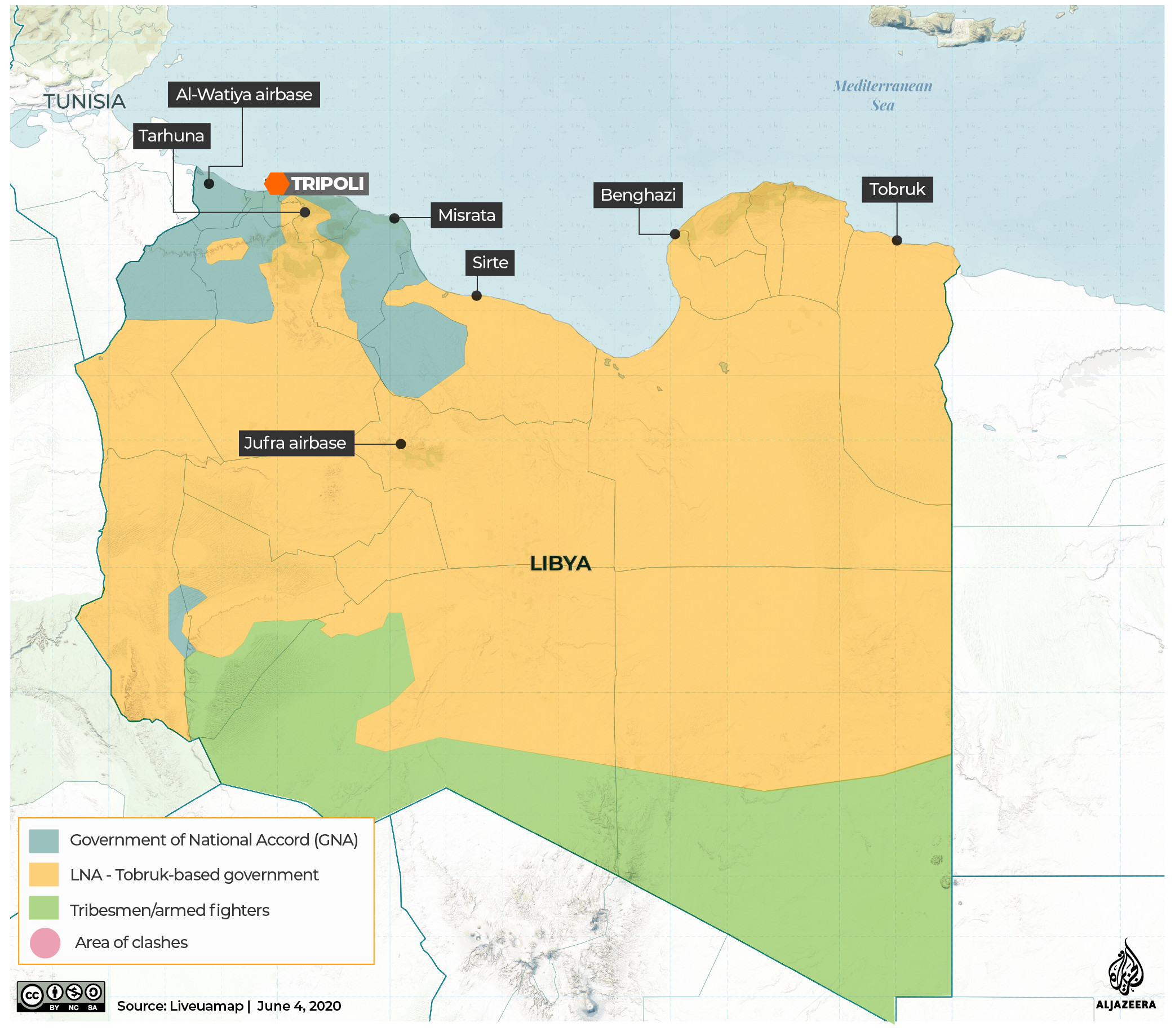

The territory controlled by various Libyan factions before June 5. (Al Jazeera/Liveuamap)

The Kaniyat and Haftar Lose Tarhuna

Mohammed and his brother Abd al-Rahman, both of whom had been sojourning abroad, returned home to guarantee their community’s continued participation in Haftar’s campaign. Haftar was now benefiting from the combat assistance of the Wagner Group, a Kremlin-linked mercenary group. In response to Mohsen’s death, the Kanis executed dozens of prisoners. But inside and outside the municipality, the ranks of Tarhuna natives challenging the Kanis kept growing. That, combined with GNA’s support, gave rise to periodic ground incursion attempts on the town’s edges. The attacks became significant in February 2020. By then, Turkey had begun bringing into Tripolitania a significant number of Syrian fighters as mercenaries to bolster the Government of National Accord’s forces. The subsequent month, the latter shuttered a key road from the littoral into Tarhuna. Backed by a relentless campaign of Turkish drone strikes, which on a few occasions killed innocent civilians, the GNA coalition diminished Haftar’s ability to send supplies into Tarhuna, whether by land or by air. During those months, the Kani brothers felt squeezed even more, a sentiment that intensified their hallmark tendency to eliminate anyone who looked like they could converse with the enemy.

Mohammed was hellbent on pursuing the war on Tripoli as long as possible, and so was the notoriously prideful Haftar. In that regard, the Kanis’ habit of eliminating suspected dissidents along with their families, came in handy: Whatever measures they felt were necessary to conserve their territory and keep the offensive going, it made no difference to the Libyan National Army and its foreign benefactors. Thousands of mercenaries and private military contractors from Russia, Sudan, and elsewhere assisting the Libyan National Army leaned on Tarhuna as their rear area. So did armed units loyal to Muammar Qadhafi’s ideology from Wershefana, a town to the west of the capital, and elsewhere.

On May 18, 2020, Haftar lost al-Wattiyah, a large air base near the Tunisian border. A momentary entente between Ankara and the Kremlin soon followed, during which Russian mercenaries withdrew from northwestern Libya. Hundreds of Wagner personnel left Tarhuna in broad daylight, dealing Haftar’s war effort a fatal blow. When, in the final days of May, overpowered Libyan National Army units began fleeing Tripolitania, the Kaniyat opened fire to prevent them from leaving the front line. On June 5, when resistance against the Turkish-backed coalition’s attacks became a physical impossibility, the Kaniyat retreated from Tripoli and, along with their families, fled their hometown. Upon entering Tarhuna, Government of National Accord forces and the Tarhuna exiles aligned with them looted stores, burned buildings and carried out revenge killings against perceived Kaniyat accomplices. These actions by the Government of National Accord and its allies also constitute potential war crimes, a fact which pro-Haftar diplomats and lobbyists are already using to deflect attention from the mass graves containing the victims of Haftar’s allies.

Members of the Kaniyat and their families are now scattered. Thousands are in Ajdabiya, Benghazi and other areas in Libya’s east. Some Kaniyat fighters have mobilized as backup as part of the Libyan National Army’s resistance effort against the Government of National Accord near Sirte. Many in the Haftar camp now repudiate and reject the Kaniyat, but they will not investigate, let alone arrest them.

This brief history reveals a conflict that has little in common with mainstream depictions of Libya. It shows, for instance, that partition wouldn’t solve anything. Yet it is always in the interest of both the foreign meddlers and the Libyan elites closely allied with them to portray the Libyan crisis as one simple binary antagonism or another: Cyrenaica versus Tripolitania; security versus Islamism; integrity versus corruption; neglected periphery versus urban privilege; etc. None of these shortcuts are viable. Libya’s complex and ultra-local disputes warrant a far greater level of granularity.

The serial murdering of innocents by the Kaniyat since 2011 undermines yet another tenacious myth: that of a Libya made of monolithic city-states and tribes neatly united behind one political stance. This was precisely the illusion Haftar wanted to promote by orchestrating February 19’s national conference in Tarhuna, less than four months before his coalition collapsed there. The communications effort, which had necessitated logistical prowess amid the raging war, was meant to project the troubled town as the nerve center of Arab and tribal legitimacy in Libya. The implicit message was that only Haftar’s coalition, headquartered in eastern Libya, is a safe, natural fit when it comes to governing the “true” population of Libya. Last month’s discoveries belie all of this. For many years before 2019, it was the Libyan National Army’s designated enemies, the Islamists and revolutionaries, who aided and abetted the Kaniyat as they instituted their rule-by-murder model. But starting in early 2019, Haftar endorsed the same approach for the purposes of a larger war, which resulted in an acceleration of the abuses in Tarhuna.

Not only that, Haftar’s involvement also introduced a foreign dimension that didn’t exist in Tarhuna before 2019. Once the Libyan National Army embraced the Kaniyat, the crimes on the local population served a specific geopolitical utility, not a merely parochial one. Several foreign states backing Haftar’s war, such as the United Arab Emirates, Egypt, Russia, and France, now had an incentive to see the marshal and the Kaniyat hold it at any cost. Civilian killings, which picked up after April 2019, just happened to be one of the tools to control a territory deemed vital to a wide military operation. The United Arab Emirates, France, and Egypt often tout the Libyan National Army as a champion in the fight against extremism. Even the White House did in April 2019. But in Tarhuna, if not other places, those states — whether knowingly or unwittingly — invoked the war on terror as a way to conceal extremist practices and help perpetuate them for more than a year.

Libya’s tragedy is far from over and foreign meddlers, including Turkey and Egypt, may grow even more brazen. The discovery of the mass graves in Tarhuna is an opportunity for Western and other publics to question the dangerous manner in which their governments play rhetorical games and obfuscate, only to allow outside interference to continue in Libya — even when that involves the routine murder of innocents less than 400 kilometers from the European Union.

Jalel Harchaoui is a research fellow in the Conflict Research Unit of the Clingendael Institute based in The Hague. His work focuses on Libya — in particular, the country’s security landscape and political economy.

Image: NATO