Preparing for War in the Fog of Peace: The Transatlantic Case

How do allies plan for war when they have different visions of how or with whom it might be fought? Strategic success is as much about adaptability as it is about plans. From Clausewitz to Yogi Berra, strategists know that prediction is a losing game, and that fog and friction will arise in unexpected ways. Alliances in a “fog of peace” have an added challenge: Their adaptations to external developments must themselves be adapted to the domestic politics of each of their members.

In a fog of peace, domestic political economy considerations are decisive. In the context of NATO and the European Union, strategic and operational planning, capabilities development, threat assessments, and burden-sharing initiatives will all be subordinate to domestic and European Union-level political economy factors, like fiscal, industrial, and labor policy. Policy-makers seeking to improve transatlantic burden-sharing and improve the set of capabilities available for conflict should therefore align such domestic and European Union-level factors with their desired defense outcomes. In short, they should focus on constraints in policy areas that they can affect, and that shape defense investment choices. These areas include mitigating the effects of E.U. fiscal rules and austerity on defense spending, rationalizing transatlantic markets for defense articles, and addressing the effects of labor markets on defense capabilities.

Increasing Uncertainty

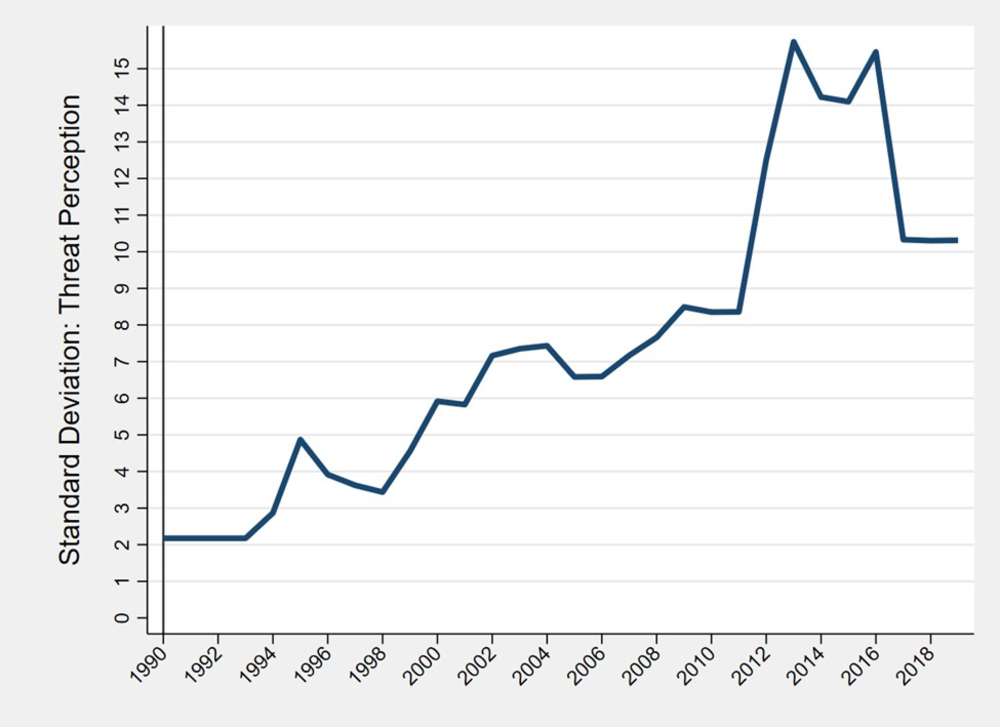

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic and its strategic consequences, uncertainty was becoming the primary characteristic of the international system. While great-power rivalry appears to be the order of the day, there is no consensus on what such rivalry means for existing security institutions. Questions abound, from whether or how to preserve or reform these institutions to how regional security arrangements might be realigned. This strain is apparent in the transatlantic community – from Brexit for the European Union to “brain-death” for NATO, and COVID-19 for both. The only certainty is uncertainty. In a lengthier piece, we identified quantitative and qualitative evidence of increasing uncertainty: an unmistakable trend toward greater diversity in allies’ perceptions of threats. Figure 1 visualizes that trend.

Figure 1: Standard Deviation in Threat Perceptions as Expressed in National Security Strategies, NATO and E.U. Members

Source: Graphic by Jordan Becker.

Order, Alliances, and Strategic Planning

How do states plan for war in such a strategic environment? Strategic planning is often neither “threat based” nor “capabilities based,” but resource-based, and rightly grounded in politics. While great powers may devise strategies based on structural factors like the distribution of relative power in such environments, national and regional political economies weigh heavily in shaping strategy and resource allocation, particularly among the small and mid-sized powers that comprise the system of alliances on which America’s strategic approach centers.

Defense planning, or “the practice of military strategy in grand strategy,” converts political will and community resources into defense capabilities, which planners think will bring strategic effects. Even assuming that states are rational, unitary actors, such planning lacks focus in the absence of a clearly identified and singular rival or threat. NATO is a multinational security community whose membership spans three continents and whose members adjoin not just the Atlantic Ocean, but also the Arctic and Pacific Oceans, the Baltic, Black, and Mediterranean Seas, as well as Russia, Iran, Iraq and Syria. A multiplicity of interests – whether conceived through the logic of consequences or that of appropriateness – should therefore be considered a driving feature of the network of alliances in America’s security portfolio.

How, then, does the transatlantic security community prepare for war in these conditions? With the return of great-power rivalry, how do the United States and its allies seek to enhance deterrence and defense postures in multiple regions? Planning, resourcing, and developing the forces that strategists think will have the strategic effects needed to address these challenges is a long-term process, requiring institutionalized systems.

The multilateral structures of the European Union, and particularly of NATO, represent the most developed form of such systems. How does this institutionalization function? First NATO, and more recently the European Union, have sought to institutionalize defense planning with routinized processes. Updated and outlined for the public in 2009, NATO’s Defence Planning Process provides “a framework within which national and Alliance defence planning activities can be harmonised to enable Allies to provide the required forces and capabilities in the most effective way.” While the European Union does not have a single process analogous to NATO’s, its Coordinated Annual Review on Defence aims to “foster capability development addressing shortfalls, deepen defence cooperation and ensure more optimal use, including coherence, of defence spending plans,” and its Capability Development Plan “defines future capability needs from the short to longer term.”

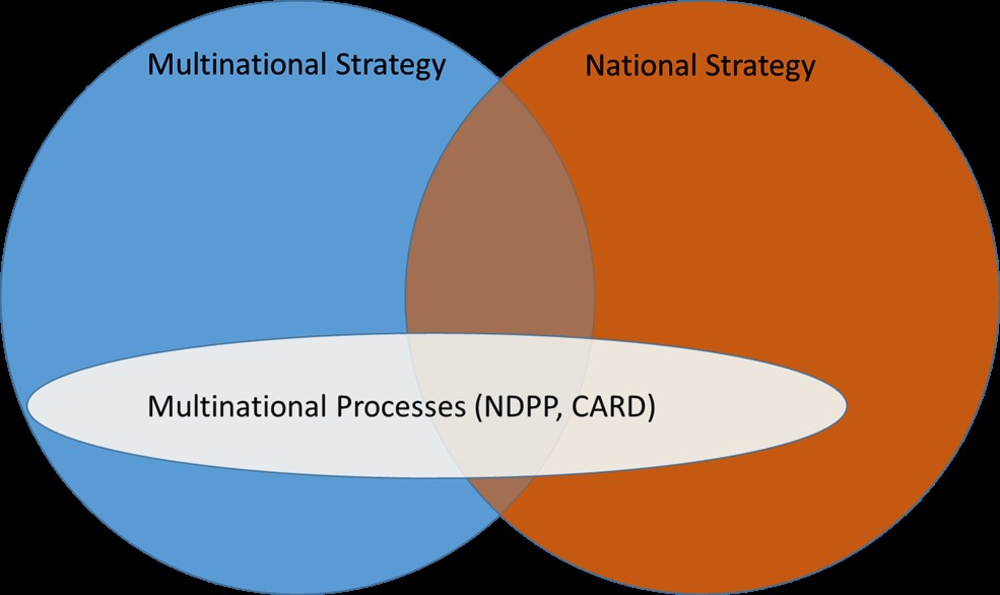

Edward Luttwak explains the necessity of such processes: “the development and production of sophisticated modern weapons … takes years,” requiring states to “devise peacetime force development strategies that economically build forces for wars they can only anticipate.” Figure 2 visualizes the challenge of devising such force development strategies in the multilateral security communities that anchor the current American-led order. National strategies only partially overlap with collective strategies, and processes like the NATO Defense Planning Process and the E.U.’s Coordinated Annual Review on Defense do not affect the entirety of members’ national strategies – strategy ultimately remains a sovereign matter for nations.

Figure 2: Strategy in a Security Community

Source: Graphic by Jordan Becker.

Nonetheless, NATO’s Defense Planning Process at least has a reasonable record of influencing allies’ defense planning choices. Allies accepted and agreed on, for example, all new capability targets at their June 2017 defense ministerial meeting. In fact, the Defense Planning Process is unique in consensus-based NATO in that allies can override a veto, imposing a capability target on a nation over its objection if all other nations agree that it should accept the target – a system known as “consensus minus one.”

The Limits of Institutions

Yet there inevitably are areas of national strategy that a process alone cannot shape. We maintain that national strategic cultures, national political economies, and E.U. macroeconomic and fiscal policy decisively influence how countries allocate resources to defense – before NATO and E.U. planning processes take place. Specifically, the more Atlanticist (a preference for a transatlantic approach to European security, in which the United States’ role is central) a country’s national security strategy was, the more it contributed to shared operational priorities during NATO’s “out of area” period (from 2000 to 2012). As European states experience increased unemployment, they “slightly decrease top-line defense spending in response to unemployment, while shifting much more substantial amounts within defense budgets out of equipment and into personnel.” E.U. members respond similarly to supranational (E.U.) fiscal constraints agreed to by heads of state and government as part of the Maastricht Treaty on European Union, and “monitored” (enforced) by the European Commission.

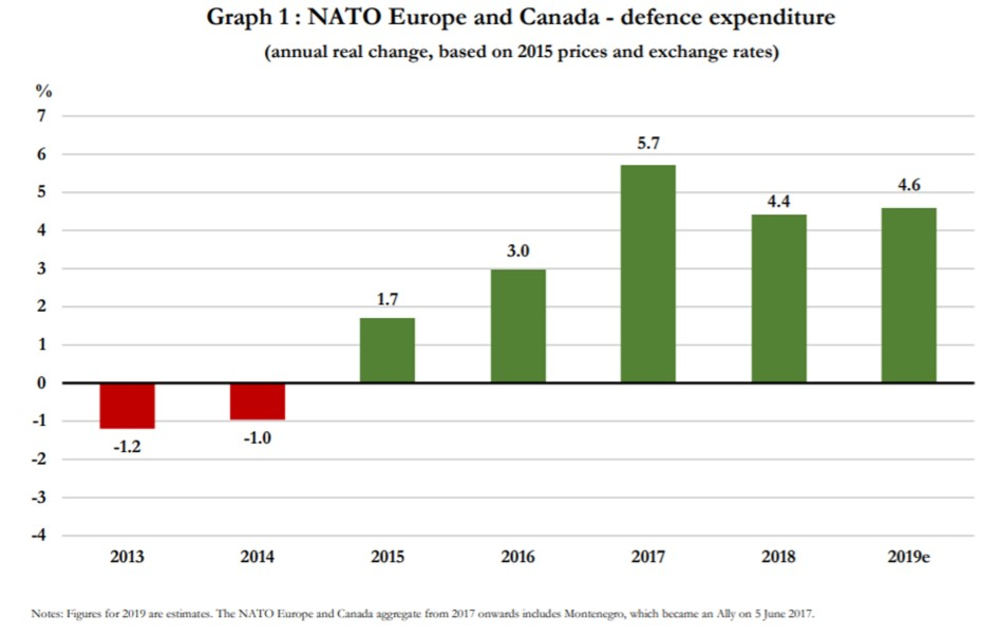

Processes cannot address these tough choices, which amount to rival claims on strategic resources, but politico-strategic dialogue may. For example, when NATO allies agreed to a “pledge on defense investment” at their 2014 Wales Summit, their heads of state and government gave broad but clear guidance not only to defense ministries to “meet[] capability priorities,” but also to finance ministries to “reverse the trend of declining defense budgets.” Two years later, E.U. heads of state and government formally adopted the NATO goals of moving toward spending two percent of GDP on defense and 20 percent of defense spending on equipment modernization. Early indications are that these political agreements are having some effect on resource allocation, as Figure 3 shows. European allies’ defense spending increased by $87 billion from 2014 to 2018. That this would occur in spite of disagreements regarding threats, economic fragmentation within Europe and the broader transatlantic community, and fiscal austerity in the European Union, points to the importance of cultural factors like Atlanticism. However, as Figure 3 also shows, increases may be stalling – a transatlantic divide may harm burden-sharing and, perhaps paradoxically, weaken Europe as a strategic actor.

Figure 3: Annual Real Change in Defense Spending, NATO Europe and Canada

Source: NATO, Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2013-2019), 2020.

NATO and European Union agreement on exigent defense investment guidelines, as well as the downstream effects on coordinated capability development, point toward other opportunities for the two organizations to cooperate strategically. This is especially true given the tight interconnection between the economic strength of the transatlantic community and its military strength. For example, NATO and the European Union could build on current cooperation proposals to include the grand strategic area of resource allocation, ensuring that NATO and E.U. defense spending goals are not in competition with E.U. fiscal rules for scarce resources. Italy’s 2015 defense White Paper, for example, suggests the possibility that some defense spending “could be excluded from the thresholds of the Stability and Growth Pact.”

Trouble Behind, Trouble Ahead

At some level, all states must prepare for war. Robert Osgood called alliances “latent war communities” – they are designed for that purpose. Indeed, Bear Braumoeller’s recent work extends Charles Tilly’s insight that “war made the state and the state made war” to international orders, which he argues prevent war among their members but are dangerous to non-members. Processes like those that NATO and the European Union have developed during the last eight decades of relative calm and prosperity are central to the transatlantic community’s ability to prepare for, and perhaps forestall, future wars. They are the best tools its members have to convert political will into capabilities that they believe will have strategic effects, like deterring adversaries or, if necessary, defending national territory and shared interests.

Processes are, however, no substitute for grand strategic vision. Such vision animated the creation of both NATO and the European Union. There is now a strong case for a bolder vision of transatlantic cooperation in defense planning and grand strategy to keep the “fog of peace” from turning into the “fog of war.”

What might such a vision look like? Some scholars have proposed to address the fog of peace by “rediscovering geography” to regionalize NATO defense planning, enabling allies to focus on capabilities that are most directly relevant to their own strategic priorities. Others have argued that it is time for Europe to seek – and achieve – true strategic autonomy, either by “Europeanizing” NATO (whereby the United States would reduce its footprint in the alliance and concentrate on its strategic challenges elsewhere), or by subsuming NATO into a broader European political-security framework. Even the possibility of extending France’s nuclear deterrent to its European allies has been raised, first by French scholars discussing “nuclear solidarity,” and then by President Emmanuel Macron, who invited European partners to “be associated with the exercises of French deterrence forces” in the interest of a “true strategic culture among Europeans.” Macron further clarified his intent in an interview with Wolfgang Ischinger at the 2020 Munich Security Conference, pointing to an “unprecedented dialogue” on nuclear deterrence among Europeans.

Challenges abound. First, transatlantic discord creates challenges for European Atlanticists, making it more difficult to align national strategies, and may even incentivize countries to curb defense spending to appeal to domestic electorates that bristle at external pressure. Second, the combination of economic recession and fiscal austerity that plagued Europe during the 2008 crisis appears likely to return in a more virulent form, which is almost certain to dampen defense investment.

Taking Europe’s “destiny in its own hands” is easier said than done. Years of low defense investment, the complicating effects of Brexit, the rise of populist politics across Europe, and uncertainties about Turkey, among other issues, cloud prospects for greater European defense autonomy. While retaining the transatlantic bond, in an era of great-power competition when conflict would almost certainly not be confined to one operational theater, it may be wise to encourage allies to “concentrate on those tasks for which they are most geographically suited.” For example, Baltic Sea states could focus on defending their territory from Russian aggression, while states along the Mediterranean could focus on combatting terrorism and building partner capacity – each without fear of being criticized for inadequately supporting allies. Doing so would help link operational and strategic planning to threat assessments, while also helping to blunt conflict among allies about defining the array of threats, risks, and challenges that characterize the emerging security environment. It would enable the transatlantic security community to incentivize and leverage the national defense planning efforts of its members. Specializing like this would enable institutional work to focus on harmonizing, which encourages burden-sharing, as opposed to dominating, which incentivizes free-riding. But such specialization demands trust, which is currently in short supply in the transatlantic community and beyond.

Jordan Becker was Senior Transatlantic Fellow at the Institute for European Studies at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel during this research. He is currently the U.S. Liaison to the French Joint Staff, and an associate researcher at the Institut de Recherche Stratégique de l’Ecole Militaire (IRSEM) and Sciences Po’s Center for International Studies (CERI). He completed his PhD at King’s College London in 2017, and he is a lieutenant colonel in the United States Army. He previously served as defense policy adviser to the U.S. Ambassador to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and as Military Assistant and Speechwriter to the Chairman of the NATO Military Committee (International Military Staff). He is solely responsible for his research, which does not reflect any official U.S. government position.

Robert Bell is CEO of National Security Council (NSC), a Limited Liability Corporation consulting firm, and Distinguished Professor of Practice at the Sam Nunn School of International Affairs at Georgia Tech. He is a PhD candidate in International Relations at the Fletcher School at Tufts University. He previously served as Senior Civilian Representative of the Secretary of Defense in Europe and the Defense Adviser to the U.S. Ambassador to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, as well as Assistant Secretary General for Defense Investment on NATO’s International Staff. From 1993 to 1999, he was President Bill Clinton’s NSC Senior Director for Defense Policy and Arms Control.

Image: NATO