Tell THIS to the Marines: Gender and the Marine Corps

In 2013, I delivered my first history conference presentation at Ohio State’s Mershon Center of International Relations and Security Studies. A festschrift for Geoffrey Parker and John Guilmartin, two giants in the field of military history, was also a part of the program. A woman in the audience asked these eminent historians if they ever saw themselves incorporating more gender analysis into their work. Both apologetically admitted that they had paid little attention to women in their scholarship when they probably should have. Based on their answers, when they heard “gender” they must have thought “women’s history.” I was a bit surprised. These renowned scholars misunderstood what I, then a graduate student from the University of Alabama, thought was a straightforward question. I learned then that gender is too often associated solely with women’s history and feminist studies — things many students and professors of military history care little about.

Too many military historians and military professionals ignore the utility of gender as an analytical tool. This is not surprising at all given how so many scholars and professionals steer clear of it in their graduate studies and write it off as something they have no use for. There might be another reason gender analysis is seen as something to avoid: It is a highly politicized topic. Claiming to have studied gender can be seen as a way of identifying oneself as a “woke” leftist — who might view the military with disdain. This is simply not true in every case, particularly among those who have studied gender in the military, to include your humble author.

Why is this a problem? By avoiding gender as a lens of analysis — for whatever reason — scholars and professionals have denied themselves a tool that would help the armed services study, understand, and improve upon their institutional cultures. Gender analysis is certainly not a panacea, nor is it useful everywhere. It’s a tool to answer questions about the past, particularly questions regarding culture. Even though I’ve studied masculinity in the Marine Corps carefully, I do not define myself as a gender historian. Using it has taught me that one cannot effectively explore military institutional culture without addressing gender in some form or fashion, regardless of the era being studied.

Gender as an Analytical Tool

Gender as an academic and analytical concept is quite simple, and it does not have to be polemical or esoteric. It is first important to understand the difference between biological sex and gender. The former has to do with the chromosomes and reproductive organs that define biologically whether one is male or female. The latter has to do with cultural beliefs regarding how men and women should act, dress, speak, and live their lives. Therefore, gender in this context is socially constructed because its norms are defined by the social context in which it exists. It is also a cultural construction because it is a manifestation of what people think is appropriate behavior for men and women. Gender has a performative element, meaning cultures generally have notions regarding how men and women should act in certain situations.

These ideas are never static. Rather, they are and always have been in a continuous evolution punctuated by conflict and economic, political, and geographic changes. For much of the history of Western civilization, however, the public sphere (politics, industry, war) was the man’s domain while the private sphere (the home) tended to belong to the woman. The connection between military service and war to the masculine sphere is perhaps the oldest and most lasting cultural trend in Western history. Because of the predominance of men in the military up to this very day, what it has meant to be a soldier, sailor, or marine, has been informed greatly by society’s definition of what it means to be a man. Questions about masculinity are strong and crucially important cultural connections that most military historians ignore.

Heather Venable’s new book, How the Few Became the Proud, is a prime example of a book that uses gender effectively as a tool to better understand military culture. It joins Bobby Wintermute and David Ulbrich’s Race and Gender in Modern Western Warfare, Craig Cameron’s American Samurai, and Aaron O’Connell’s Underdogs as one of a small number of history books that ask tough questions about the Marine Corps’ institutional culture. Venable argues that marines of the late 19th and early 20th century could not claim a clearly defined mission within the defense establishment and shows how they revolutionized their public relations efforts and advertising to promote an image of marines as more elite and disciplined than soldiers, and more masculine than sailors.

Although gender is not the main impetus behind her analysis, Venable uses it to explore how the Marine Corps constructed an elite image of itself. Armed with a history of amphibious landings, including the 1914 Vera Cruz operation, the Publicity Bureau printed posters of marines storming beaches while the Navy waited offshore. These were attempts by the Marine Corps to align themselves with society’s notions of mainstream masculinity, which valued strength and the courage to risk one’s life in battle as the most idealized forms of manliness. Marines, therefore, “engendered landing parties,” at the Navy’s expense because it made sailors appear decidedly less manly in comparison.

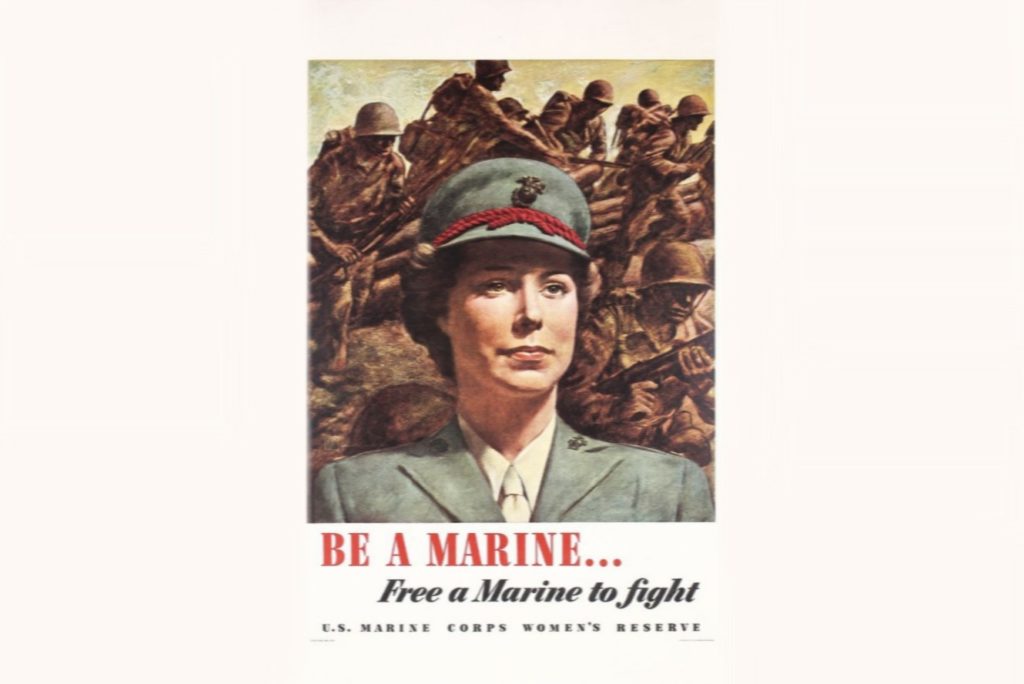

By the time America entered World War I, the Marines’ new and improved public image was strong enough to survive what should have been the biggest threat to its identity: the inclusion of women in the ranks in August 1918. Marine performance on the Western Front in the summer of 1918 bolstered a claim to elite status, but the enlistment of the first female marines did a great deal to “hypermasculinize” the Corps’ institutional culture. The marines at the Publicity Bureau revealed incredible savvy by turning this challenge into a public strength. Female marines took over several hundred clerical jobs within the Corps, which freed up a small number of male marines from work that many Americans thought “feminine.” The Marine Corps was not interested in overturning gender roles. The inclusion of women, ironically, allowed marines to align more closely with not only normative but idealized gender roles that relegated women to desk jobs and men to the front lines. Venable helps reveal that the Marine Corps’ identity, both in terms of public image and practical fact, was white and male. These were essential prerequisites to being or becoming a marine.

Military Historians Need to Get Better at Culture

Military professionals tend to rely mostly on traditional operational military histories to learn about the past and prepare for the future. The commandant’s reading list is a prime example of this. It is full of novels, biographies, and “instrumentalist” histories (a term used by the late Craig Cameron over a quarter-century ago) produced mostly by authors with a military background who study history either to celebrate the history of their service or promote certain reforms. There are other books in this genre, such as battle narratives that impose order on messy and confusing events through a cohesive narrative. Both types of military history are attractive to readers and researchers in part because they deal mostly with easily measurable data such as people, units, casualty figures, official reports, orders, and after-action reports. This is not necessarily a bad thing, considering the long-term challenges the Corps faces today regarding force design and mission readiness. Interest in military culture is growing, however, which is good.

Despite this growing interest, perhaps the most disappointing work on military culture to come recently is The Culture of Military Organizations, edited by Peter Mansoor and Williamson Murray. It reflects my earlier encounters with the complete avoidance of gender as an analytical tool among most military historians. In its examination of how military institutions develop biases for offensive action, technology, education, promotion, and even certain kinds of history, the anthology is generally useful. But I remain disappointed with what it calls its efforts to “revise and expand the discussion of military effectiveness by focusing on the role played by organizational culture and strategic culture in its development.” Analyzing military culture without addressing the obvious racial and gender makeup of the institutions is to ignore a critically important aspect of each institution’s culture. It’s a frustrating omission on the part of respected and established scholars who, frankly, should not be ignoring something as blatantly obvious as how the predominant gender of an institution could affect its culture.

As a Marine Corps historian, the first chapter of Mansoor and Murray’s volume I read was Allan Millett’s on the U.S. Marine Corps between 1972 and 2017. His characterization of the Marine Corps as disparate tribes unified within a tribe was derivative of Victor Krulak’s First to Fight. Much of the chapter is about how the Corps has dealt with demographic changes. This leads him to address racial and gender issues that the Corps has struggled with in the past and continues to struggle with today. While he admits to “masculine dominance values that exist” in the various communities of the Marine Corps, he chose not to explore what exactly those values are or how they were formed. As I read the rest of the book, however, the realization struck me that Millett actually wrote one of the better chapters: At least he acknowledged that such a thing as “masculine values” existed in the first place.

The book starts out on a good note. Leonard Wong and Stephen Gerras’ first chapter rightly points out how culture is a many-sided, multidimensional thing that can be studied on multiple levels. They offer a model for other historians in the volume to use when writing their pieces on military organizational culture. They base it on Geert Hofstede’s Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness and recast it as GLOBE dimensions of military organizational culture. Of the nine dimensions, gender egalitarianism is one of them. Yet, most subsequent chapters flat-out ignore that element of the book’s supposed guiding system, and the few who use the model omit the gender dimension. This is a shame because students of military institutional culture could have learned much more from these chapters if the authors chose to use gender as an analytical tool. For a book that warns readers to be aware of “cultural biases,” the omission of gender as an analytical tool reflects these authors’ own analytical biases.

Changing Culture Through Education

Today, marines are asking themselves tough questions about capabilities, culture, and education. In these efforts to consider the Marine Corps in the 21st century, those who would ignore Venable’s work and others like it solely for works like The Culture of Military Organizations do so at their own peril. Commandant David H. Berger has taken pains to carefully elucidate who exactly the Marines are and who they are going to be in the next generation. But military professionals who keep their blinders on, and who focus solely on vocational concerns, risk losing sight of the big picture. That big picture includes combat readiness and public opinion. The marines in Venable’s book had the vision many today seem to lack. They crafted and institutionalized a singular identity and deployed it to the public, who mostly bought it, which helped keep the Corps in existence in the first place. The public bought the image crafted by the Publicity Bureau in part because they liked the idea that the Marine Corps would make men out of their sons.

How will shifting the Marine Corps’ focus to small boat units, expeditionary advanced bases, and deterrence by denial operations in the South China Sea affect the Corps’ public image and recruiting? Marines dealing with these questions should read Venable’s book. They will see that gender matters to discussions of operations and tactics, particularly when it comes to recruiting the manpower needed to fulfill the Corps’ evolving missions. Marines will need to be more technologically proficient than the basically trained infantry of the past. The Marine Corps wants more women in its ranks but has consistently had trouble recruiting and retaining them. To address this issue, the service needs to think more carefully about its culture and the public image it promotes if it wants to attract the best talent. The Corps needs to be mindful of whether its recruiting videos and literature are overly geared toward attracting males, which could potentially turn away thousands of qualified women.

The Marine Corps’ newfound popularity during the World War I era had to do with the “mystique” it created for itself. White manhood greatly informed that mystique, which continues to have serious implications for the Marine Corps today. The emotional response to an issue can tell a lot about the importance of a topic to a particular group. Last year’s marine identity debates were fascinating but they were quite measured and subdued compared to the shrill voices raised by opponents of female integration in the infantry. Outspoken marines in and out of uniform have come out of the woodwork to maintain and protect what they see as the Corps’ combat effectiveness. From my perspective, what is really at stake for them is the masculine image of the Marine Corps, particularly the infantry. The comment section of this Wall Street Journal article gives a taste of this problem.

It is concerning that marines today may think discussions of winning on the battlefield are enough for success in the 21st century. They certainly are not, at least not in the Marine Corps’ case and certainly not in the era of the all-volunteer force. The Marine Corps must continue to pitch the service to young Americans as one that will benefit and uplift their lives, much as marine recruiters did before World War I. Today, Americans are more sensitive than ever to perceived exclusions based on gender, race, and sexual preference, which is part of the reason for the backlash against the Corps’ latest recruiting video. Marines risk losing the “mystique” they once had with the American people if they continue to downplay or ignore how their own masculine culture can create serious problems on the home front — like the Marines United scandal did. Another risk would be failing to learn from their own history of dealing with problems of gender and integration.

Could marines out-soldier soldiers? Were they more manly than sailors? Maybe, but it’s important to remember that to promote traditional masculine values that are useful in combat, such as courage, toughness, and physical prowess, is one thing. To promote them to the point that the Marine Corps develops a reputation for bloodthirstiness and misogyny, however, is to veer into the realm of “hyper-masculinity,” a notoriously more toxic form of manliness. Someone who is “hyper-masculine” these days is one who enjoys being violent and aggressive. This March 2018 study suggests that this issue pervades the Corps’ organizational culture. Recruiting posters, videos, and movies notwithstanding, it is not the Marine Corps’ goal to create hyper-masculine killers. The goal is to create highly trained marines who can win on the battlefield and one day return to the society they have helped defend as honest and productive citizens.

Venable’s book teaches that what has kept the Marine Corps in existence is winning on the battlefield and developing and maintaining positive relationships with the society it serves through advertising and public relations. The Marine Corps needs leadership that can do both, and it needs educators who can and are not afraid to use analytical tools like gender to teach them how. How the Few Became the Proud should be considered a standard source from which to learn. Were the marines more elite than the Army and Navy at the start of the 20th century? Objectivity requires historians and military and naval professionals to say, “not necessarily.” But today’s Marine Corps can learn from Venable that these claims do not have to be true; they must be believed by the institution itself and by a significant portion of the public.

To make marines and the public believe these things requires careful attention to the Corps’ own culture, which means public image, identity, and, yes, gender. There is a great deal of talk these days from marines regarding “sacrificing sacred cows.” The most ubiquitous archetypal public image of the marine since the Corps’ founding in 1798 is white and male. What about that “sacred cow”? Mansoor and Murray warn of the “danger of disconnect” between the U.S. military and the rest of society. Military institutions that do not align themselves to the surrounding political, social, and strategic situation risk paying a high price, on the home front and against peer competitors abroad. To ignore gender as an analytical tool, and as a way to gain insight into your culture, is to risk worsening the disconnect between the military and U.S. society and court disaster in the realm of public relations. I’m not asking for alterations to the curriculum of the School of Advanced Warfare or at the Command and Staff College. No one needs to turn themselves into gender experts. But, if the Marine Corps values education and culture as much as it says it does, then the leaders of this service will take Venable’s work seriously and put her thorough research to good use.

Dr. Mark Folse is currently the Class of 1957 Post-Doctoral Research Fellow at the United States Naval Academy where he’s teaching Navy and Marine Corps history and working on his manuscript entitled The Globe and Anchormen: U.S. Marines and American Manhood, 1914-1924. He is also a Marine infantry veteran (2002 to 2006) with service in both Afghanistan and Iraq.