Foreign Policy is Much More Than a Liberal vs. Conservative Brawl

Colin Dueck, Age of Iron: On Conservative Nationalism (Oxford University Press, 2019)

Nationalism – like power, empire, or hegemony – is one of those political science concepts that defy easy categorization and measurement. Too often, defining the term is in the eye of the beholder, and subject to their biases. Worse, in the Trump era, the definitions have become politicized. Reviewing Yoram Hazony’s book, The Virtue of Nationalism, Mark Koyama describes this quandary well:

The problem is pervasive… In the parlance of my native discipline, economics, the author continuously selects on the dependent variable. Take any historical state or event. If something turns out to be good, attribute it to nationalism. If something is bad, attribute it to the opposite of nationalism. Thus, we are told that Nazism and Japanese imperialism had little to do with nationalism.

Much the same can be said of ‘conservative nationalism’ as a concept within the Republican foreign policy conversation. If a decision turned out well, it was clearly an application of conservative nationalism. If it turns out badly, it was the result of excessive idealism or globalism among foreign policy elites. Neoconservatives – a core part of the Republican foreign policy apparatus even today – are routinely portrayed as Democratic and cosmopolitan interlopers. Alliances and military force are good if they’re part of a conservative nationalist strategy, but bad when they arise from Wilsonian theories about multilateralism or democracy promotion – even though the practical results may look the same.

In large part, this schizophrenia is the result of a Republican foreign policy elite trying to rapidly pivot from the traditional foreign policy consensus to their new Trumpian political reality. Pasting a veneer of ‘conservative nationalism’ onto the existing foreign policy consensus allows elites to maintain long-running support for U.S. alliances and active forward presence, while joining in the Trump-inspired chorus criticizing the so-called ‘liberal international order.’

This helps to explain one core thesis of Colin Dueck’s new book on American foreign policy: that conservative internationalism is, in fact, a form of conservative nationalism.

Got it?

It’s ok if you don’t. That sort of cognitive dissonance – which forms the core of this interesting but frustrating book – is par for the course in today’s conservative foreign policy circles. Other Republican thinkers have sought to suggest that a synthesis of internationalist, nationalist, and realist ideas is now necessary for foreign policy. Dueck instead subsumes these divisions under a common “conservative nationalist” rubric. Unfortunately, this means that the book starts to shed light on an important shift in U.S. foreign policy, but obscures its most interesting arguments under an overly simplistic liberal-conservative framework.

Like Hazony, Dueck is therefore guilty of selecting repeatedly on the dependent variable. He presents three strands of Republican foreign policy thought: nonintervention, hawkish unilateralism, and conservative internationalism. All are forms of ‘conservative nationalism,’ a term he doesn’t really define, but implies is driven by a focus on sovereignty over cosmopolitanism. With the exception of George W. Bush, each Republican president discussed in the book is presented as some flavor of conservative nationalist. Likewise, each Democrat is an exemplar of liberal internationalism. In practice, it feels a little like everything good must be conservative and everything bad must be liberal.

To some, this might sound good in theory, but the practical applications are confusing. Dwight Eisenhower’s military buildup and creation of NATO? Conservative nationalism, because he correctly feared the Soviet threat. Donald Trump’s criticisms of NATO? Conservative nationalism, because he’s emphasizing burden-sharing. Barry Goldwater’s proposal to double down in Vietnam? Conservative nationalism. Richard Nixon’s choice to conduct a ‘fighting retreat’ from Vietnam? Also conservative nationalism. Only the younger Bush fails to meet the bar, taking that “uncompromising nationalism so dear to American conservatives, [and] redirecting it toward a remarkably high-risk, assertive, idealistic, and even Wilsonian strategy within the Middle East.”

The result is an ill-defined overview of a foreign policy approach whose prescriptions appear to change randomly over time; the reader is left wondering if conservative nationalism isn’t merely a synonym for realism or the ‘national interest,’ with variation explained by simple changes in external threat perception. Within the context of an existential Cold War struggle, the narrative suggests, different strands of Republican foreign policy pulled together; in the absence of that pressure, they have started to fray.

Global versus National

The theoretical weakness of Dueck’s book is a shame, because the global-national divide in foreign policy to which he alludes is increasingly salient. And it is confined neither to the right nor to the United States, from the rise of right-wing anti-immigrant governments in Eastern Europe, to the debacle that is Brexit, and an increasingly nationalistic Chinese government running ‘re-education camps’ for religious minorities.

Some of these shifts reflect classic ethnic nationalism: the protection of in-group identity through immigration barriers, natalist policies, or other insular steps. Others are more the result of a classic conception of civic nationalism and sovereignty found in the United States and some other Western, pluralist democracies. Both kinds of nationalism are found in American politics today. Indeed, the literature on American exceptionalism notwithstanding, it’s impossible to argue that Trump’s immigration policies are driven by anything other than ethnic nationalism.

From the point of view of foreign policy, however, it’s the question of sovereignty that is most intriguing.

At heart, this is a question of whom foreign policy serves, one that both political parties – not just Republicans – are grappling with as they fumble towards the post-Trump era. The classic formulation of this question, as Heather Hurlburt has described, is about domestic politics; the idea of the ‘national interest’ is usually oversimplified in assuming for example,that the interests of elites are aligned with the masses, an assumption that has rarely – if ever – been entirely true.

But there is also a national-transnational cleavage at work here, as structural changes in the international system make it more difficult for foreign policy to benefit Americans and foreign countries at the same time. Are trade deals and forward military presence about promoting greater global openness or about advantaging American businesses and workers? Are alliances about protecting American security or the security of foreign states? Should Americans intervene militarily overseas to protect the human rights of foreign citizens when it will cost them in blood, treasure or even security?

None of these are new dilemmas. Dueck’s book shines when he highlights the importance of these divisions in the pre-World War II era. But thanks to the Soviet threat and America’s preponderance of power after the Cold War, they were relatively easy to ignore. As the unipolar moment ends, however, it is far more difficult to argue that America’s national interest is good for the rest of the world, or – conversely – that America’s role as global policeman is actually good for Americans.

On the conservative side, as Dueck’s book suggests, this is primarily an argument about sovereignty. Conservatives like John Bolton have long been skeptical of multilateral organizations, treaties, and alliances. During Trump’s tenure, classic conservative internationalists – who once talked about defending democracy, alliances, or American global ‘leadership’ – have found themselves in the uncomfortable position of trying to defend treaties and alliances by tying them concretely to U.S. national security. Like Dueck, some are increasingly making the argument that Republican foreign policy leaders ought to abandon support for free trade and press allies on cost-sharing in order to maintain public support for a large U.S. overseas military presence.

On the Democratic side of the aisle, the debate is less about whether multilateralism is good. All seem to accept that multilateralism is more morally attractive and practically effective than unilateralism. But there is a significant divide between classic liberal internationalist hawks and a growing intervention-skeptical progressive wing of the party. The former accepts classic Wilsonian principles, arguing that it’s America’s duty to uphold international norms like the Responsibility to Protect, and to engage in democracy promotion. The latter are supportive of these ideas in theory, but far more skeptical of America’s ability to improve things in practice, and worried about the indirect impact of such policies on the safety and security of Americans.

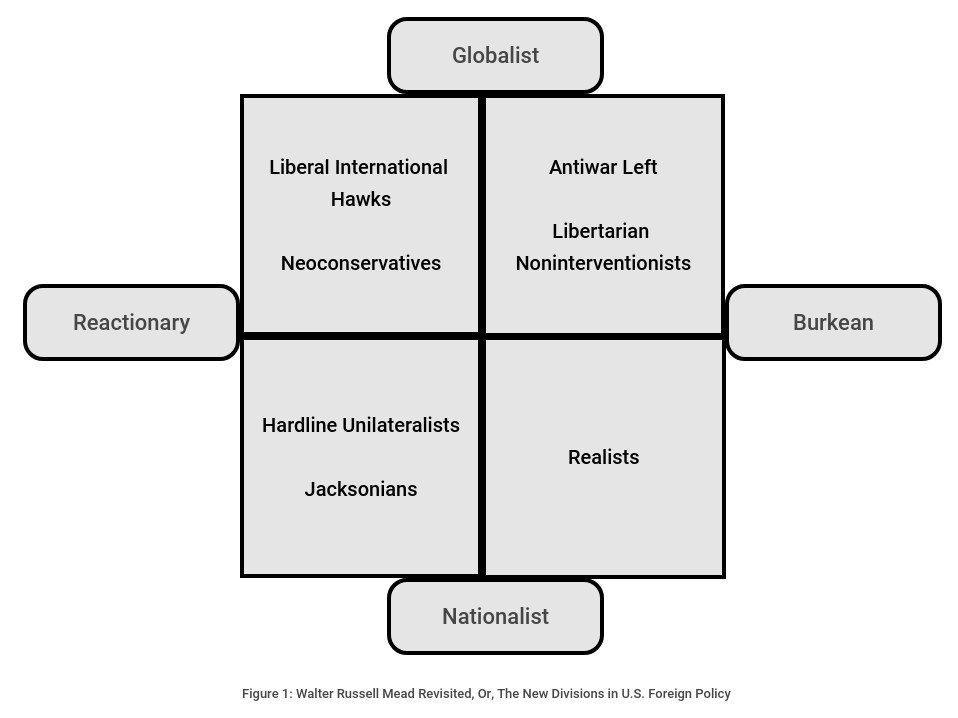

Where does this leave us? A now standard typology of American foreign policy – as formulated by Walter Russell Mead – divides people into Jacksonians, Jeffersonians, Hamiltonians, and Wilsonians based on whether they were idealists or realists, and whether they took a global or a national view of foreign policy.

The former division has typically been viewed as far more important, undoubtedly why even a book about nationalism like Dueck’s is framed as idealism versus pragmatism. Instead, the evidence suggests that the global-national distinction he draws out may be the central cleavage in American foreign policy in coming years.

Reactionaries and Burkeans

Taken together, these trends suggest that Mead’s typology may not be as effective as it used to be in explaining today’s divisions in American foreign policy. Dueck begins to address this when he tries to describe what differentiates conservative nationalism from liberal views of foreign policy; he concedes that all varieties of U.S. foreign policy “wrestle with the distinctly American questions of how best to promote popular forms of self-government overseas.”

Indeed, it is impossible to argue that liberal visions for American foreign policy don’t share this priority with conservatives; the easiest criticism one can level at liberal internationalism is its privileging of human rights and spreading democracy over key security concerns. The conservative-led War in Iraq, and the liberal-led intervention in Libya both sought to reshape other societies to be more like America; both produced massively detrimental results for U.S. national security on a practical level, from the rise of the self-proclaimed Islamic State to the European refugee crisis.

Even realist or anti-war visions for U.S. foreign policy don’t ignore the question of how best to maintain or even spread American values. Hans Morgenthau, godfather of classical realism, was always careful to clarify that realists are not amoral. As he put it:

Political realism does not require, nor does it condone, indifference to political ideals and moral principles, but it requires indeed a sharp distinction between the desirable and the possible – between what is desirable everywhere and at all times and what is possible under the concrete circumstances of time and place.

Morgenthau’s writings may be out of fashion in modern academic and policy circles, but his credo is still followed by some of today’s thinkers. From the left, Bernie Sanders, has made similar arguments, noting:

Foreign policy is about whether we continue to champion the values of freedom, democracy and justice… But it’s a truth we must face. Far too often, American intervention and the use of American military power has produced unintended consequences which have caused incalculable harm.

From the libertarian point of view, Chris Preble asks, “What we can do to advance individual liberty through peaceful means?”

Source: Image created by the author.

Source: Image created by the author.

To put it a different way, there’s a good argument to be made that all Americans are idealists to some extent.

What differs is their assessment of how possible it is to reshape the world, and how aggressively to pursue that goal. Or as Adam Mount has described this split among progressives, it’s the difference between liberals – who still want to use American power to reshape other states and world politics into a more pleasing alignment – and what he describes as ‘solidarists’ – those who believe firmly in democracy and human rights for all, but are skeptical of America’s ability to achieve it, and worried about the backlash such efforts provoke.

In this world, a better formulation of Mead’s typology would jettison the idealism-realism axis and replace it with a spectrum of activism: Burkeans pursuing gradual, conservative continuity on one end, and reactionaries seeking global wholesale change on the other. The realism-idealism axis is not unimportant, but it tells us relatively less about differences in the key approaches to foreign policy today. As much as realists like myself might wish it to be otherwise, to a large extent, today’s realignment in foreign policy is less a post-World War I style rejection of idealism, and more a reassessment of means. Jacksonians like Trump want to reshape the world to America’s benefit, but as Mead correctly notes, are not idealists. The anti-war left is skeptical of America’s ability to reshape the world, but fervently believe in transnational human rights.

To better understand today’s U.S. foreign policy, then, we should instead contrast the strategies, not the ideologies, drawing a distinction between those who wish to reshape the world to their liking (the ‘Reactionaries’), and those who take a more gradual or passive approach (the ‘Burkeans’). For the reactionaries – a group that includes neoconservatives, liberal hawks, and Jacksonian conservatives – there are few problems that cannot be solved with the application of American military power. Though they each have a different rationale, all seek to reshape the world in response to some threat. For the Burkeans, a more cautious application of American power, using diplomatic and economic means is preferred; the goal is predominantly defensive.

The result is a typology that places the emerging primacy-restraint debate in the context of divisions over sovereignty, rather than the context of party loyalties. Indeed, if there is one thing of substance to draw from the emerging work on conservative and progressive foreign policy, it is that they are largely having parallel, mirror debates. To put it another way, if you put aside party labels, it becomes quickly apparent that foreign policy is still a bipartisan affair; it’s just no longer a consensus.

If we wish to understand where American foreign policy is going more broadly, therefore, the answer is probably not to seek new formulations of “conservative” or “progressive” foreign policy. Rather, it’s to look at the big questions animating debate in both political parties. Who does foreign policy serve: Americans or the world? And to what extent can Americans hope to shape the world? The answers will be far more illuminating than just another liberal versus conservative brawl.

Emma Ashford is a Research Fellow in Defense and Foreign Policy at the Cato Institute, where she studies U.S. grand strategy and the politics of energy. Her current book project – Oil, the State, and War – is an examination of the links between oil and foreign policy in petrostates.

Images: U.S. Air Force (Photo by Samuel King Jr.)