Join War on the Rocks and gain access to content trusted by policymakers, military leaders, and strategic thinkers worldwide.

When the Air Force chief of staff and secretary confirmed that the service’s budget request for Fiscal Year 2020 would include money for F-15EX aircraft, they kicked off a massive debate among airpower strategists and defense planners. Many arguments against the F-15EX focus on the need to invest in fifth-generation aircraft, specifically highlighting the F-35A, and the advantages of stealth and advanced sensors to counter Russian and Chinese threats. On the other hand, Air Force and Department of Defense leaders have focused on the need to maintain fighter capacity and keep costs down.

While interesting, the conversation isn’t addressing the deeper problem: the deterioration of the Air Force’s F-15C fleet and potential gaps in fulfilling key air superiority missions. This should not be a discussion specifically about whether the F-15EX or the F-35A is a better weapon system. Rather, discussion should focus on how to best meet airpower demands given finite resources and an F-15C fleet well past its service life and in need of considerable investment to continue flying. The Air Force, Department of Defense, and Congress should not miss the opportunity to utilize the FY20 budget to invest in a solution.

This article outlines the need for dedicated air superiority fighter aircraft and explores four options to sustain this critical capability over the next 20 years. Ultimately, new aircraft will return on investment by divesting the F-15C. The proper mix of fourth- and fifth-generation aircraft will provide the most lethal and cost-effective force using the distinct advantages of each while guarding against inherent design weaknesses of either.

F-15C: Still Important, But Nearing the End

The Air Force’s original plans would have provided an all fifth-generation fighter fleet comprising large numbers of F-22s and F-35s. Unfortunately, the Air Force can’t meet the demands of the National Defense Strategy without maintaining fourth-generation capacity.

The Air Force operates 234 F-15C/D aircraft primarily from two active-duty bases overseas and six Air National Guard installations. As a dedicated air-superiority fighter purely focused on air-to-air combat, it excels at defensive counterair missions such as homeland and forward base defense, and protection of high-value airborne assets (e.g. airborne command and control; intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance aircraft; and tankers). However, the aircraft is not stealthy and faces considerable challenges operating in contested environments with advanced surface-to-air missile systems.

This doesn’t mean the F-15C and other fourth-generation aircraft cannot contribute to a strategy focused on great power competition. There are numerous missions that do not require aircraft to operate deep in contested airspace. For example, since 9/11, fourth-generation aircraft have stood on alert 24 hours a day, 365 days a year across the country supporting air defense under Operation Noble Eagle. Fourth-generation aircraft also continue to excel at supporting combatant commander objectives across the Middle East under Operations Enduring Freedom and Inherent Resolve. Using F-15Cs for these missions frees up F-35s and F-22s for penetrating offensive counter-air and strike missions. Additionally, F-15Cs provide considerable magazine capacity and carry eight air-to-air weapons, twice the internal payload of a F-35A. In contested regions, teaming F-15Cs with fifth-generation aircraft can make the most out of both platforms. Fifth-generation platforms, such as the F-22s and F-35s, can use stealth and advanced sensors to exploit contested battlespace while F-15Cs with large external weapons payloads can target enemy formations. Together the combined force is both lethal and cost-effective, and it creates complex problems for adversaries.

As another example of why a mix of aircraft is needed, today’s small fleet of 186 F-22 aircraft are the most advanced and capable air superiority fighters in the world. Yet they have the worst mission- capable rate in the Air Force due to organizational structure, alert mission requirements, unique demands of stealth coatings, and limited training opportunities. The Air Force’s original plans to acquire 749 F-22 aircraft and completely divest the F-15C would have ensured necessary air superiority fighter capacity and capability. When the F-22 buy was terminated prematurely in 2009, this left a capacity gap and today there are simply not enough F-22s to source every air superiority mission. It is important the Air Force retain some fourth-generation aircraft that can address air defense and air superiority missions the F-22 does not have the capacity to meet.

Sufficient numbers of aircraft and squadrons are necessary to maintain readiness and sustain combat operations. For every combat squadron deployed, the Air Force needs two at home stations reconstituting, training, and preparing for deployment. Continuously flying aircraft or deploying squadrons would wear out people and equipment while driving down readiness. There must be time for maintenance and training, and while in combat, there must be flexibility to accept losses and continue operations. Fourth-generation airframes like the F-15C will be critical for enabling the F-22 and F-35 fleets to focus on high-end air superiority missions or penetrating counter-air capabilities.

So why not simply keep the F-15C? Unfortunately, the venerable fighter has come to the end of its lifespan. The last F-15C rolled off the assembly line in the mid-1980s. According to internal data from the Air Force Cost Analysis Agency, the F-15C has one of the highest costs-per-flying-hour in the Air Force, peaking at $42,845 in FY15. The Department of Defense FY2020 Budget Estimates Justification Book notes, “Many F-15C/Ds are beyond their service life and have SERIOUS structures risks, wire chafing issues, and obsolete parts. Readiness goals are unachievable due to continuous structural inspections, time-consuming repairs, and on-going modernization efforts.”

Maintenance concerns with the F-15C fleet have been continuous since a Missouri Air National Guard aircraft broke in half during flight in 2007. In recent years, F-15C squadrons faced multiple unplanned groundings for safety concerns. I personally have had several complex in-flight emergencies resulting in emergency landings, cable engagements, and a few trips to the hospital following rapid decompression events. There is good reason a former Secretary of Defense’s effort to improve fighter readiness excluded the F-15C — it is no longer possible. As aircraft exceed their service limit life, F-15C numbers will drop 52 aircraft below the current total aircraft inventory by 2023. Now, the service needs an affordable plan to fill the gap that doesn’t leave it with aging, expensive aircraft.

Solving the F-15C Readiness Challenge

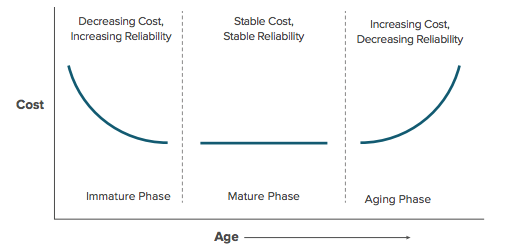

Here, I examine four options to solve this problem, each with different costs, risks, and advantages. Each option assesses the costs of operating 235 aircraft flying 250 hours per year and provides a cost comparison in replacing 80, 150, or 235 F-15C. This analysis is based upon a 2018 Congressional Budget Office report, “Operating Costs of Aging Air Force Aircraft,” which applies a theoretical model of an aircraft’s life cycle to its operating costs, as depicted in Figure 1. New systems, such as the F-35A, are assumed to be in the immature phase and achieve decreasing cost and increasing reliability. Established systems, such as the F-15EX with a production line open over 40 years, are in the mature phase and achieve stable costs and stable reliability. Finally, the F-15C is in the aging phase with increasing operating costs, calculated at 2 percent annually, and decreasing reliability. Data for this analysis, provided by the Air Force Cost Analysis Agency, utilizes operational cost per flying hour (CPFH) using total ownership costs less indirect costs, and constant year dollars normalized for inflation to 2012 (CY12).

Figure 1. Source: Congressional Budget Office based on K.R. Sperry and K.E. Burns, Life Cycle Cost Modeling and Simulation to Determine the Economic Service of Aging Aircraft (October 2001).

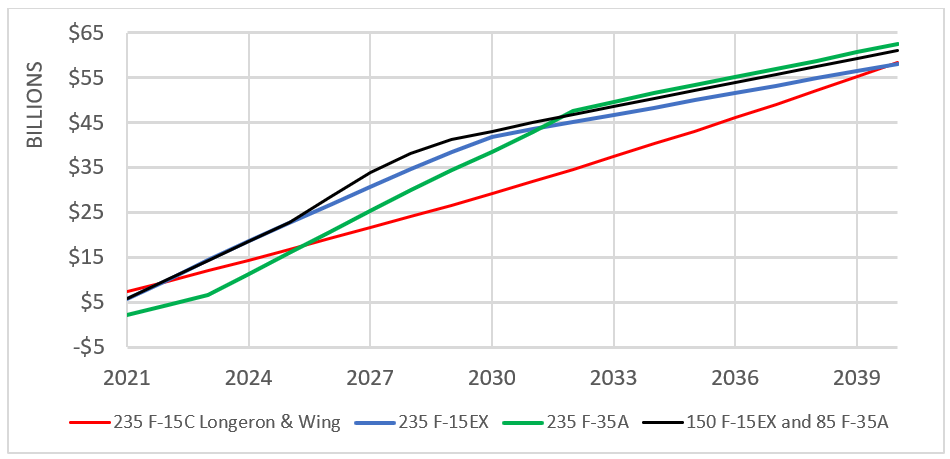

A summary of the analysis can be seen in Figure 2, which compares the cost of F-15EX and F-35A procurement and operation against modification and sustainment costs of the F-15C over the next 20 years. Figure 3 demonstrates that procurement costs of new weapon systems will be $12–15 billion more expensive in the short term than attempting to maintain older aircraft. However, procurement costs for new aircraft will be offset over time due to high operation and sustainment costs of the older F-15C.

Both Figures 2 and 3 indicate that approaching 2040, F-15C operation and sustainment costs will begin to overtake the costs of procuring and operating new weapon systems. Additionally, by 2040 any remaining F-15Cs will encounter additional structural fatigue of critical components, including the fuselage and bulkheads, and will need to be grounded again or rebuilt at significant cost and time. This will require the Air Force to make another decision in 2040 about whether to invest even more money into 55-year-old fighters or finally buy new aircraft.

Figure 2. Total Procurement, Operation, and Sustainment Costs

Figure 3. Cumulative Cost Comparison to F-15C Service Life Extension, Operation & Sustainment Costs

Figure 3. Cumulative Cost Comparison to F-15C Service Life Extension, Operation & Sustainment Costs

Option 1: Extend and Upgrade the F-15C fleet. This option would essentially accept current maintenance concerns and low readiness rates associated with maintaining 35 to 40-year-old fighter aircraft. Under this option, the Air Force would refurbish old F-15C airframes to keep them flying until 2040, while upgrading key systems to keep aircraft up to date with projected threats. According to the F-15C Program Office Estimate, critical structural components could be replaced, including longerons and wings, for $12.1 million per aircraft. Completing these repairs would take several years and readiness rates would lag as aircraft were removed from operational squadrons and sent to depots. Additional funding would be required to upgrade airframes with new avionics including $3.4 billion for Eagle Passive Active Warning Survivability System providing updated electronic warfare capabilities critical to operating in contested environments. In total, a $5 billion investment in aircraft structural repairs and over $2 billion in annual operating costs could provide another 15 years of service life.

This option is not currently being advocated by anyone, but would most likely be the result of a failure to commit resources to procuring new weapon systems. It requires the least initial investment but maintains the highest operating cost over time. Additionally, the F-15C fleet will remain at low levels of readiness and fewer aircraft will be available to support military tasking while they are being restored. Over 20 years, the Air Force would commit approximately $58 billion but still have zero operational aircraft by 2040.

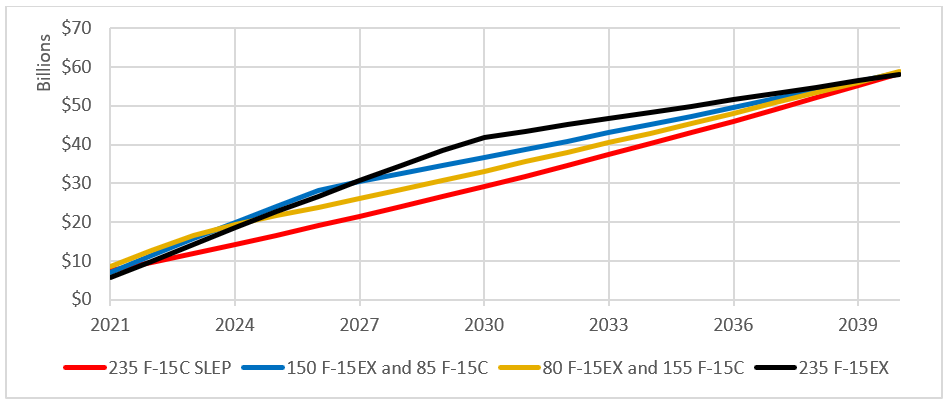

Option 2: Replace F-15Cs with F-15EXs. The Air Force and Department of Defense have been unclear whether all F-15Cs would be replaced by F-15EXs under the new plan. According to Maj. General David Krumm, the Air Force’s director of strategic plans, “There’s 80–90 percent commonality” between the F-15C and the F-15EX. Purchasing F-15EXs would allow the Air Force to divest its oldest and most damaged F-15Cs. Pilots and maintainers would not require extensive retraining, which would address readiness and pilot generation concerns. F-15EXs would provide new avionics, including Eagle Passive Active Warning Survivability System, as well as unique capabilities like a standoff weapon delivery or hypersonic missile launch platform, since the airframe would not be limited by internal weapons carriage requirements. Current F-15C bases would require little to no infrastructure development while F-15EX, F-15C/D, and F-15E fleets would have common ground equipment, maintenance, and software support.

In the near term, this option should correct readiness and capacity concerns in F-15C squadrons. F-15EX aircraft would have improved capability over the F-15Cs, though they will never have the capabilities of stealth platforms offered by fifth-generation systems like F-35As. Additionally, purchasing F-15EXs would ensure another fighter production line remains open, which is critical to the resiliency of America’s fighter production capacity. In the event of a conflict with a peer adversary, there would be considerable attrition of all fighter platforms. Maintaining factories capable of replacing fourth- and fifth-generation aircraft will be critical to sustaining combat capability and securing national security objectives.

Completely divesting the F-15C and replacing it with F-15EXs should pay for itself by 2040 by saving the Air Force from high annual F-15C maintenance and operation costs, while ensuring fighter aircraft are available after 2040 when the F-15C will have to be grounded or repaired again. But F-15EX aircraft will continue to have limitations operating in complex surface-to-air missile environments. The Air Force will need to develop new operational concepts to leverage advantages of carrying large external weapons and payloads along with technology advances in hypersonic, swarming, and directed energy weapons — all while integrating with autonomous systems, remotely piloted, fifth- and sixth-generation aircraft.

Figure 4. F-15EX Cost Comparison with F-15C Service Life Extension Program

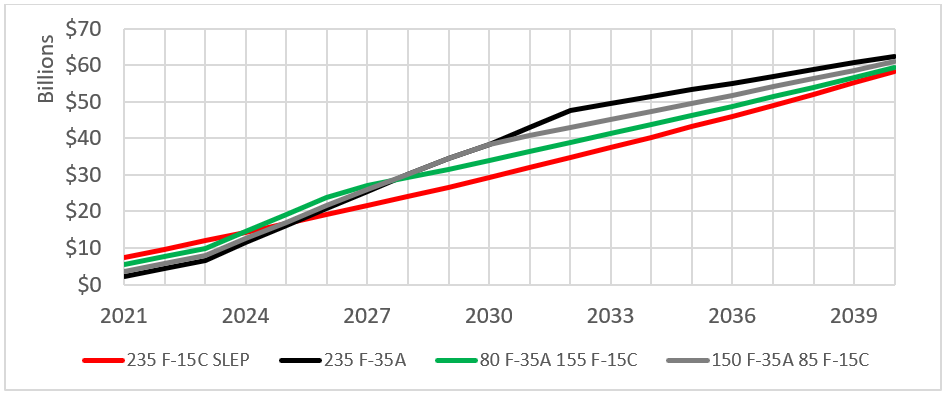

Option 3: Replace F-15Cs with F-35As. This option is advocated by some airpower strategists who recommend a significant increase in fifth-generation platforms as quickly as possible. Once F-35A aircraft are purchased and aircrew and maintenance personnel retrained, the Air Force would have a higher percentage of fifth-generation aircraft than current force projection models which, according to The Heritage Foundation, retain “hundreds of fourth-generation fighters in its fleet for the foreseeable future.” However, this option would not be executable for the next 3–5 years until a transition plan is developed, infrastructure is built, and personnel are retrained.

Increasing the rate of F-35A procurement at the current unit cost of $89.2 million is comparable with the costs of procuring the F-15EX. Yet these F-35As would incur concurrency costs — the costs of retrofitting delivered aircraft to fix known deficiencies as aircraft continue to undergo developmental flight testing during production. The Government Accountability Office estimates these costs at $2.8 million per aircraft or roughly $1.4 billion. The F-15EX should not have comparable concurrency costs as the production line is currently active and supplying aircraft through foreign military sales to Saudi Arabia and Qatar.

F-35A would also cost more to operate. According to FY18 Air Force Total Operating Cost data, each F-35A costs the Air Force approximately $7.8 million per year to operate, about 50 percent more than the F-15C annual operating cost of $5.2 million per aircraft. Costs include manpower, unit operations (including fuel), maintenance, sustaining support, and continuing system improvements.

Additionally, procurement costs for the F-35A do not include the costs and time associated with divesting the F-15C. Replacing the F-15C with the F-35A was never planned. Transitioning F-15C bases would require significant funding for construction and infrastructure upgrades to maintain F-35As instead. For reference, Vermont Air National Guard budgeted $100 million over five-years to upgrade airport infrastructure at Burlington International Airport to support F-35A operations and replace their F-16 squadron. Cherry Point MCAS conversion from F-18 to F-35C squadrons will cost an estimated $850 million in military construction between FY2016 and FY2031.

Furthermore, aircrew and maintenance personnel would need to be retrained. Readiness for those units would suffer as they stood down F-15C flying operations and retrained on the F-35A. The F-35A pilot production pipeline would be further burdened with retraining existing F-15C pilots in addition to new students. This transition period would take up to 3 years once military construction funding is approved (which has not been budgeted).

Air Force leadership would need to assess the risk of divesting the F-15C fleet earlier than expected, resulting in fewer total airframes and less fighter capacity in the next 5–10 years. This will place increased strain across the Air Force to support alert and homeland defense missions.

Finally, converting to the F-35A will significantly reduce air-to-air weapon capacity. A four-ship of F-15Cs can provide 32 air-to-air weapons, whereas a four-ship of F-35As can only carry 16 weapons internally. Future weapon and sensor integration will be more challenging for stealth platforms if they are required to be carried internally. External weapon carriage may be an option, but the aircraft would lose the advantages of stealth it was primarily designed to achieve. This shows why fully moving away from fourth-generation aircraft is currently not a viable option for the Air Force.

Figure 5. F-35A Cost Comparison with F-15C Service Life Extension Program

Option 4: Mixed Replacement and F-15C Divestment. Under this option, the Air Force procures F-15EXs at a rate of 24 per year. When F-35As reach Block 4 of their modernization plan — estimated in 2023 — they would begin to replace F-15Cs. Bases identified to receive F-35As would begin a 3–5-year transition cycle and infrastructure development in preparation for new aircraft. Specific numbers of F-15EXs and F-35As could then be adjusted based on Air Force requirements, but for the purpose of this analysis procurement of 150 F-15EXs and 85 F-35As were considered. This would spread procurement costs over a longer period and multiple budget cycles. Air Force would also have more information available based on F-35A actual operation and sustainment costs to make a more informed decision.

This option assumes some F-15Cs can fly until 2029 with no upgrades and incurs the highest procurement cost over the next 10 years totaling $22 billion. This investment would provide the best balance of fighter capability and capacity while simultaneously improving readiness for F-15C squadrons by replacing them with F-15EXs in the near term.

This way, the Air Force has more time to implement a transition plan to convert some F-15C squadrons to F-35A squadrons and achieve a higher percentage of fifth-generation aircraft in the fighter inventory as some propose to Congress. Again, buying F-35A now will not address current F-15C readiness and capacity concerns. New F-35As will not be able to operate from current F-15C bases until they receive their own ground equipment, facility modifications, and personnel training. The Air Force can put iron on the ramp but will not have pilots to fly them or maintenance personnel to maintain them until those bases are transitioned.

Recommendations

If the Air Force wants to address F-15C fleet health and readiness concerns while maintaining current capacity and capability, it should purchase F-15EX as quickly as possible. Completely divesting the F-15C fleet by 2030 and replacing entirely with F-15EX could achieve $300 million in savings by 2040 and ensure operational aircraft are available to support the National Defense Strategy.

If operating in highly contested environments is the primary and overriding concern, F-35As will provide the most capability, although with significantly diminished weapons capacity and future weapon integration challenges. Moreover, replacing F-15Cs with F-35As will require a multi-year installation transition period, during which current F-15C squadron readiness and fighter capacity will decrease until F-35A procurement and retraining are completed and base infrastructure is built. This course of action assumes high risk in the near term by accepting decreased fighter capacity and readiness. If all F-15C aircraft can be divested by 2030 and F-35A operation and sustainment costs continue to decrease, this approach could return on investment by 2045.

The optimal solution may include a mix of F-15EX and F-35A to replace the F-15C. This involves starting F-15EX procurement immediately to address F-15C readiness concerns and assess the viability of transitioning some, but not all, F-15C squadrons to the F-35A. If the assessment is positive, the Air Force could begin the 3–5-year transition cycle to build infrastructure supporting the F-35A and cross-train personnel at selected bases. Additional F-15EX and F-35A aircraft would then be purchased between 2025–2029 to complete the divestment of the aging F-15C fleet. While this will result in high procurement costs, the Air Force will return on its investment close to 2040 by divesting the F-15C and its high annual operating cost. The F-15EX will provide superior firepower and magazine capacity to complement the advantages of stealth provided by the F-35A and F-22. This option spreads procurement costs over several budget cycles, addresses readiness and capacity concerns, provides increased capability, allows time for F-35A basing to establish required infrastructure, and lowers annual operating costs by getting rid of 40-year-old fighters.

There are costs, risks, and readiness concerns with any choice. Fourth-generation aircraft provide unique capabilities such as large weapon capacity and external carriage for future weapons and sensors which will complement fifth-generation fighters, enabling both airframes to use their most lethal capabilities. Fourth-generation aircraft will continue to preserve finite resources by sustaining fighter capacity in a much more cost-effective way than fifth-generation aircraft can.

The F-15C has performed spectacularly over the past 40 years and helped to establish American air superiority as a certainty in modern conflict. Yet, air superiority is not guaranteed in future conflict against rising powers. F-15C aircraft need to be replaced and new capabilities developed to enable U.S. warfighters to dominate future adversaries. An initial purchase of the F-15EX will help cycle out old and expensive aircraft and restore readiness, all while improving capacity and capability. Going forward, additional purchases of F-15EXs and F-35As should be seriously considered. If the Air Force and Congress miss this opportunity and are left with a broken fleet of F-15C aircraft, they will have failed the nation, the joint force, and America’s warfighters.

Brad Orgeron is a Lieutenant Colonel in the U.S. Air Force. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Air Force, Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.