This is How Turkey’s Incursion into Syria Could Get Bogged Down

The Turkish government made the decision to intervene directly in the Syrian conflict, sending tanks and a mechanized infantry battalion across the border into Jarablus and the Ar Rai. The first phase began while U.S. Vice President Joe Biden was in Ankara for a visit. The Turkish military is fighting alongside rebels hailing from various factions, first, to clear Islamic State from the border; second, to prevent the Syrian Kurds from taking more territory west of Manbij; and, third, to hold territory taken. This combined force has succeeded in the first and second goals, is preparing for the third, and now there are is talk of a fourth goal: a push further south to take the city of Al Bab from the Islamic State. The forces deployed are small in number and were adequate for retaking territory from the Islamic State (ISIL) along the Turkish-Syrian border. To push to Al Bab, Turkey would have to increase the number of ground forces to offset the weaknesses of the Arab and Turkmen militias fighting in the area.

The Turkish military has taken advantage of favorable terrain to advance quickly along the border, taking sparsely populated territory ISIL appears to have retreated from. A fight for Al Bab, an urban area with a pre-war population of 130,000,would be more difficult (Estimates on the current population vary between 20,000 and 60,000). ISIL has reportedly withdrawn to the city from the border areas. The city’s urban terrain would offer a challenge for advancing armor and mechanized infantry, negating the advantages Turkey relied on for operations along the border.

ISIL has been degraded after more than a year of U.S.-led bombing. The group is currently fighting a two and a half-front war in Syria with the northern border of its territorial area coming under sustained assault from the Kurdish YPG, the most dominant militia in the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). On this front, the United States is using the so-called light footprint model, wherein it embeds special operations forces with local elements, in this case the SDF, and leverages American airpower to take territory. Turkey has lent support to this campaign, despite its deep misgivings about the heavy participation of the YPG, which is the Syrian branch of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), an insurgent group currently fighting Turkish military forces in Turkey’s southeast.

Turkey’s military intervention in Syria diverges from the current American war strategy. Ankara is taking a more conventional military approach, using an armored brigade to spearhead its assault directed by a combination of regular soldiers and Turkish special operations forces. The Turkish approach has a heavier footprint and thereby entails a different set of risks. The two main risks for advancing Turkish armor are anti-tank guided missiles (ATGM) and improvised explosive devices (IED). The Turkish military can minimize these risks if it chooses to limit its military goals, hug the border, and focus on holding territory taken and, perhaps, expanding the zone under Turkish control as far deep as Dabiq. This city is sparsely populated and is only 10 kilometers from the border.

The risk of Turkey getting more deeply involved and perhaps bogged down in Syria has implications for the United States, a treaty ally, the ultimate guarantor of Turkish security, and the leader of the anti-Islamic State coalition. In the shorter term, the main threat to Turkish forces is the mass proliferation of ATGMs and IEDs in the Syrian conflict. In the longer term, Turkey runs the risk of taking territory, but not being able to leave because the forces fighting alongside it cannot be trusted to hold territory. In this scenario, the Turkish military may have to remain in Syria until ISIL is defeated or a political solution is reached and the fighting stops. A push as far south as Al Bab would lengthen supply lines, increasing the risks to Turkish convoys sent to resupply advancing armor and infantry. A key element in Turkey’s decision and the potential for its success on the ground will be how it deals with the IED and ATGM threat to Turkish armor and the “day after” goals of the Turkish intervention force. This, in turn, will have policy implications for the United States as it continues the air war against ISIL and managing its relationship with Turkey. The ousting of ISIL from the border is a good thing for the war, but a bogged down Turkish ally is not.

An ATGM Rich Environment

The proliferation of ATGMs in Syria is unprecedented, with various outside actors providing these systems to favored rebel groups. The various actors inside Syria have also taken regime ATGMs. Others have fallen into the hands of groups after they defeat their rivals on the battlefield. In August, Syrian rebels fired a total of 118 ATGMs, according to Qalaat Al Mudiq, an open source analyst tracking the daily use of anti-tank missiles in the Syrian conflict.

The Turkish military has already come under fire, losing five tanks to ATGM fire in the first 14 days of operation “Euphrates Shield.” These strikes have killed 4 soldiers and wounded a handful of others. Press reports suggest that Turkish special forces and infantry are conducting dismounted patrols to blunt the ATGM threat.

The logistics needed to support current tank operations appear to be based in Turkey, although pictures have been posted online that show support vehicles deployed alongside tanks in Syria. The proximity to the border allows for tanks to patrol in Syria and return to Turkey for refueling and maintenance before crossing over the border again for regular patrols. This arrangement decreases the secondary risk to the refueling and maintenance vehicles that tanks rely upon to sustain operations. If Turkey pushes farther from the border, perhaps as part of an offensive for Al Bab, the logistics chain would likewise grow longer. The Islamic State could then target these supporting trucks rather than the advancing armor. This would inflict casualties on the Turkish military and minimize risk for the ISIL attackers, and it could harm tank operations if they are cut off from overland supply.

Turkey could certainly try to compensate for this vulnerability through the introduction of more ground forces or the use of local forces to protect Turkish convoys. The Turkish forces could also choose to advance to the outskirts of Al Bab and use long-range tank fire and airstrikes to pound ISIL inside the city. However, once Turkish-backed forces try to take the city, the realities of urban combat would take hold, forcing street-to-street fighting. Such a scenario raises a broader question about the insurgent forces Turkey would bring to the fight. If these forces are cobbled together from different groups primarily based in Idlib, as was the case in the fight for Jarablus, would they be recognized as liberators or as an outside force incongruent with the city’s typical demographic? This may not matter in the short term, but could become an issue once ISIL is territorially defeated and morphs back into a more typical insurgent force willing to use disgruntled locals to harass occupying forces in perpetuity — tactics reminiscent of Al Qaeda in Iraq’s harassment of U.S. forces in the “Sunni triangle.”

The deeper Turkey moves into Syria, the more difficult it will be to evacuate wounded or dead soldiers. The Turkish military appears to use the “Golden Hour” rule for medical evacuation. The military has set up a field hospital in Soylu, near Jarablus, and press reports indicate that wounded soldiers requiring more medical attention are sent to a hospital in Nizip, a city 31 kilometers from the border. The Turkish military currently relies on ground transportation for medical evacuation. This arrangement works because of the proximity to the Turkish border, something that would obviously change should Turkey push deeper into Syrian territory.

If the Turkish government eventually requires helicopter transport, the United States would have to work to de-conflict airspace, something that requires cooperation with Turkish officials, a task that should not be that hard because rotary- and fixed-wing aircraft fly in different flight corridors. However, the introduction of Turkish helicopters raises other tangential risks, like small arms fire and man-portable air-defense systems (MANPADS). The Turkish Air Force could compensate for such threats by flying low and fast, largely over the flat terrain just across the border in Syria. However, flight operations would bring Turkish forces into closer proximity to Syrian and Russian aircraft, particularly along the regime’s front line with ISIL some 15 kilometers south of Al Bab. This would require some element of de-confliction to avoid an unintended escalation.

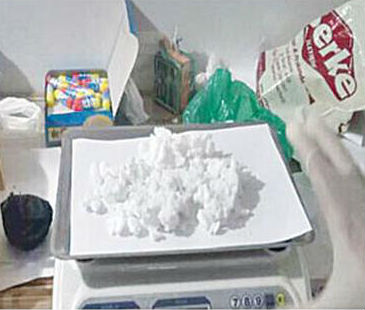

Improvised Explosive Devices: The ISIL Bomb Factory in Gaziantep

The M60A3 is a flat-bottomed tank and, like its eventual successor in the U.S. inventory, the Abrams, is at risk from IED attack. The Islamic State’s predecessor, the Islamic State of Iraq, used IEDs in urban environments to mitigate the United States’ overwhelming military and technical advantages. IEDs are the Islamic State’s most potent weapons, and it has deployed them across the battlefields of Iraq and Syria on a “quasi-industrial” scale, according to Conflict Armament Research, an organization that tracks weapons proliferation in conflict areas. A 20-month study tracing the supply of components used in Islamic State IEDs indicated that Turkey is the “most important choke point for components used in the manufacture of IEDs by [Islamic State] forces.”

The Islamic State relies on components procured in Turkey for the assembly of IEDs, including the fertilizer used to derive the explosive (ammonium nitrate), the device for remote detonation (Nokia mobile phones), the detonator cord, aluminum powder/paste, and the detonators. To date, few open source pictures show intact ISIL IEDs, which prevents analysts from drawing conclusions about their design. However, in Turkey, the Twitter handle @140journos tweeted a link to a Turkish police report documenting the investigation into an Islamic State-linked attack on the Ankara train station in November 2015, which killed 103 civilians. The link has since been deleted, but I have a copy of it in my possession.

The Turkish press had previously reported extensively on this police document, but had primarily focused on the movement of Turkish Islamic State members before the attack — a group that I examined in detail in previous articles for War on the Rocks. The police report also includes an inventory of materiel seized that reveals Turkish Islamic State members procured the components for IEDs in Turkey, in addition to assembling complete devices in Gaziantep.

A picture taken during an October raid indicates that Turkish ISIL members were manufacturing two types of explosive devices. The first, a suicide vest, appears to rely on Composition B explosive, most likely scavenged from ordnance or purchased on the black market in Turkey or Syria. The vests, according to different pictures, show independently packaged charges, each with independently packed shrapnel. Importantly, in a separate picture, the bomb-maker appears to use two detonators: an electronic primary switch with grenade fuses serving as back-ups. These vests are well-designed and far superior to those used in the recent wave of terror attacks in western Europe. In those attacks, the vests were filled with TATP, which breaks down quickly after mixing and must be used relatively quickly compared to Composition B, according to an explosives expert I interviewed.

Turkish bomb-makers also used fertilizers to acquire ammonium nitrate, most probably first using a grinding machine before mixing the powder with water to make a slurry, baking it, and then peeling the top layer off. The ammonium nitrate is then ground again and mixed with fine aluminum flake, leaving the bomb-makers with a potent device safe for travel. The police document lists all of the items required for this process, in addition to 27 Nokia telephones.

The evidence from Turkey indicates that ISIL remote detonates IEDs, a challenge for advancing armor, even if the Turkish units currently operating in Syria are equipped with jammers. As evidenced by the manufacturing process in Turkey, the bombs are relatively sophisticated and the bomb-makers enjoy ample access to the ingredients, some of which are sourced in Turkey and linked to Turkish companies.

Turkish tanks can avoid IEDs by staying off well-travelled roads. However, the maintenance and fuel trucks that must accompany them can only travel on roads, rendering them susceptible to IED attacks. In southeastern Turkey, the PKK has used IEDs heavily since July 2015, often attacking armored military vehicles travelling on rural roads. These weapons now account for a plurality of Turkish casualties in the latest phase of the insurgency.

Implications for the United States

The Turkish intervention has yielded largely positive results for the narrow goal of pushing ISIL from the Turkish-Syrian border, its primary supply route. In the opening days of the operation, ISIL’s retreat allowed for the SDF to move north of the Sajur river, coming as close as eight kilometers to the Turkish border on August 26, according to data on Syria Live Map. During the opening days of the Turkish operation, allied rebel units clashed with elements of the SDF.

The United States managed to broker a tentative ceasefire after the Turkish-backed operation reclaimed territory the SDF had previously taken north of the Sajur River. Turkey denies that a ceasefire is in place, but all open source evidence suggests an agreement was reached. The agreement has held and succeeded in preventing further clashes between Turkish and its allied rebels on one side and the SDF on the other along the Sajur River. The United States has an incentive to use “airstrike diplomacy” to encourage all sides to focus on the Islamic State by withholding support from Turkish, Arab, Turkmen, and Kurdish units engaged in fighting each other rather than ISIL.

As I noted, if Ankara chooses to expand military operations to Al Bab and engage in street-to-street fighting with the Islamic State, Ankara’s firepower advantage would be offset by the realities of urban combat. It is unclear whether the forces Turkey is currently fighting alongside in the Euphrates Shield operation are numerous enough to take and hold the territory required an operation against Al Bab, while concurrently holding territory elsewhere. Turkey could opt to send more troops to offset any shortages — a scenario that would increase casualties and bog down a NATO ally in a nasty civil conflict.

It is also unclear if the Turkish armed forces have the capacity to fight two counterinsurgency campaigns simultaneously. The Turkish Armed Forces have certainly weakened the PKK in this latest round of fighting inside Turkey, but the group continues to carry out near-daily attacks on Turkish security personnel in the southeast.

The United States should pursue a multi-pronged policy approach, built upon the understanding that Turkey’s offensive in Syria and its counter-insurgency efforts in the southeast are interrelated. Washington should encourage a PKK-Turkish ceasefire inside of Turkey to decrease Turkish threat perceptions about the YPG in Syria and open up possibilities for Turkish support to broker local ceasefires between Arab and Kurdish groups in northern Syria.

The United States need not reinvent the wheel. Washington could adopt Turkey’s pre-July 2015 policy as its own and update elements of Ankara’s previous ceasefire agreements with the PKK to reflect the updated reality in northern Syria. Turkey’s attitude toward the PKK/YPG has changed considerably in the past three years. In May 2013, the Turkish government and the PKK began to implement a multi-step process of confidence-building measures designed to be a first step toward ending the decades-old insurgency. The PKK was asked to withdraw from Turkey to northern Iraq, where they would then disarm, and eventually some would be granted amnesty and return to Turkey.

The PKK in turn demanded that the Turkish government pass a legal measure guaranteeing that withdrawing fighters would not be targeted or arrested. This process broke down almost immediately, with the PKK refusing to leave and the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) refusing to pass the legislation. Still, talks continued up until March 2015. The United States could proactively approach Syria-based Kurdish militants about setting up a similar mechanism, whereby PKK members could withdraw to northern Iraq or Syria, where they could then join the fight against ISIL or staff administrative positions in the quasi-governing structures in Kurdish held territory. In return, the PKK should be asked to declare a unilatealceasefire, while the Turkish government announces a willingness to return to peace talks.

If this happens, the United States could then approach Turkey about working with both the YPG and Turkish-backed rebel groups to reach local ceasefire arrangements with the SDF. These ceasefires in turn could be based on Turkey’s own position vis-à-vis Bashar al Assad and the Syrian regime: specifically, that Assad can stay on during a potential transition, but would abdicate power after a set period of time, giving way to a governing structure that would account for all of the major groups active in the fight, including various regime militias. The exceptions, of course, would be the Islamic State and Jaysh al Fateh al Sham, Syria’s rebranded Al Qaeda affiliate.

This policy proposal will be incredibly difficult to implement and in all likelihood will not bear fruit in the near term. The Turkish government has few incentives to agree to the aforementioned terms, largely because it has re-militarized the Kurdish issue, going as far as to indict members of the legal, pro-Kurdish Democratic Peoples’ Party (HDP). Turkey’s current approach may only strengthen political support for the nationalist Kurdish movement and detract from concurrent government actions designed to decrease support for the PKK in the southeast.

Should it decide to expand its operations along the Sajur River front and support operations to take territory from the SDF, the Turkish government faces the risk of more Kurdish nationalist backlash. Any such action would further strengthen the PKK’s political narrative and galvanize Kurdish support for the group — the exact opposite intention of any coherent counterinsurgency effort. It also risks involving Turkish ground forces on a third front with an insurgent actor whose parent organization, the PKK, has demonstrated the ability to sustain an insurgency for decades. The United States has little sway over Turkish decision-making, but does have the benefit of “strategic patience.” The United States can wait out this phase of the conflict, only to revisit the aforementioned proposals once the Turkish government and the PKK eventually decide to re-open peace talks.

The United States has a strong interest in the Turkish military succeeding in Syria. Washington has an equal incentive to try and keep Turkey’s goals limited to the holding of territory taken from of ISIL’s on the border, while also trying to rein in any efforts to expand the scope of operations to include serious urban combat in Al Bab. On the political side, a successful military campaign could help to restore morale in a Turkish military that has suffered numerous purges to the officer corps following the failed coup attempt on July 15th. The Turkish military faces two serious threats, but can minimize these risks if the scope of the operation remains limited to the border and does not expand into urban areas.

The Turkish government will make its own decisions about the next phase of Euphrates Shield. Regardless of the direction chosen, the risks from both ATGM and IEDs will remain. The United States has an opportunity to use the incursion to continue discussions with Turkey about the interrelated goals of a PKK-Turkish government ceasefire, concurrent YPG/SDF-Arab rebel group ceasefires in Syria, the defeat of ISIL, and broader efforts to reach agreement on the future of Syrian governance.

Aaron Stein is a Resident Senior Fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East.

Image: Turkish state