Think Small: Why the Intelligence Community Should Do Less about New Threats

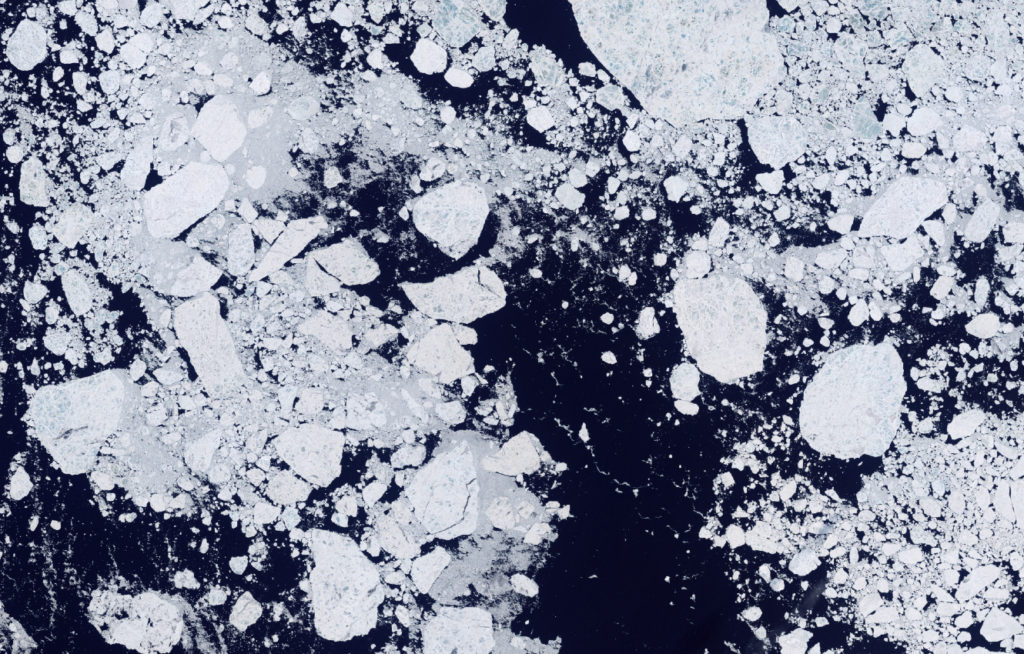

A week into his administration, President Joe Biden announced that he was “putting the climate crisis at the center of United States foreign policy and national security,” and directed the intelligence community to draft a national intelligence estimate on the implications of climate change. In so doing, the president injected new urgency into an old question: What counts as a national security threat?

For intelligence agencies, the traditional answer has revolved around foreign military powers. The architects of the U.S. intelligence community designed a bureaucracy whose main focus was watching the Soviet Union, assessing its conventional and nuclear capabilities, and searching for signs of attack. After the Cold War its focus shifted to terrorism and support for military operations, as the United States undertook a series of humanitarian interventions and state-building campaigns.

Recent years have witnessed an even more profound change. A growing chorus of analysts argues that security is not primarily about guarding the nation from hostile states or great powers. War is in decline, they say, and acts of terrorism against Americans are rare. The real dangers are transnational threats like climate change and pandemics. Nothing has a more tangible effect on the safety and well-being of American citizens. The odds that any of us will be affected by war or terrorism are vanishingly small. The odds that all of us will suffer from transnational security threats are rising.

If these observers are right, then the intelligence community requires an overhaul of its organizational culture, its analytical tools and methods, and its relationship with private sector researchers. Critics have proposed the creation of new positions, like a national intelligence officer for climate change, that would help coordinate analyses of actorless threats and send a signal of the community’s new priorities. At a deeper level, they urge the intelligence community to abandon its obsession with secret information, and take advantage of the openly available analytical tools and private sector knowledge that will help it come to grips with overlapping transnational security challenges. Agencies possessing classified information should elevate open sources, cultivate durable relationships with academic researchers, and share their findings. This will be hard, because it represents a cultural break for institutions that are dedicated to stealing secrets and temperamentally shy about working with anyone without a clearance.

These recommendations seem commonsensical, even obvious. But there are problems with all of them. Even if we recognize that “security” means more than protection against military threats, it is not clear that reshaping intelligence will help matters. It could make them worse.

Secret Intelligence and Public Policy

Shifting intelligence agencies away from secrecy reduces their usefulness to policymakers. There is a huge amount of publicly available information on transnational threats that leaders can draw upon when considering policy responses. The vast majority of what we know about climate change and pandemics comes from dedicated climate scientists. But there are some important details that are not in the open. Policymakers entering climate negotiations, for instance, have an obvious interest in knowing their counterparts’ bargaining preferences. This information sets limits for how hard they can push in the name of reducing carbon emissions, and what kinds of proposals are deal breakers.

Similarly, some information on the effects of infectious disease is likely to remain very closely guarded. States are unlikely to share details on how pandemics affect military readiness, training routines, and retention. In theory, the spread of a virulent disease could have lasting effects on the balance of power — but states are unlikely to say so. They are also reticent to share details about the origin of new outbreaks if they fear for their reputation or international litigation. Skeptics of China’s account of the origin of COVID-19, of course, make precisely this claim. Scientists and health policy professionals argue that this information is vital for preparing for future contingencies, and they urge states to be transparent in the name of the global good. But states — particularly authoritarian ones like China — have powerful incentives to remain opaque, so the next best way of gaining information is by stealing it.

Retaining credibility with policymakers is an enduring challenge. Intelligence officials are perpetually worried about being ignored. At the end of World War II, one veteran concluded ruefully that “fighting commanders, technical experts, and politicians are liable to ignore, despise, or undernote intelligence.” The problem has grown over time as more competitors for policy attention have emerged. Think tanks, private sector analytical firms, investigative journalists, and academic security specialists all seek to inform the policy debate. Meanwhile, new technologies have enabled private individuals worldwide to publicize information in real time, even from states that are hard to reach. Intelligence agencies thus face a difficult problem in distinguishing their work from the various other sources available to policymakers.

Intelligence and the Private Sector

Although the rise of actorless threats creates new difficulties for intelligence-policy relations, observers believe that it creates new opportunities for interaction with the private sector. Calls for collaboration abound, which is not surprising given the volume of freely available data on transnational security risks. On these issues, the classification barrier need not preclude a joint effort.

Collaboration also makes sense when intelligence agencies face legal barriers to unilateral action. Cyberspace, for example, is almost entirely a private sector domain, meaning that intelligence agencies will struggle against transnational threats without active cooperation from industry. The private sector rightfully demands that information sharing is a two-way street, and it stands to benefit when government agencies reveal new malware and vulnerabilities. As a result, routine interaction is best for all concerned.

But collaboration is costly if it leads to replication. Intelligence assessments of new security risks are not particularly notable if they rely entirely on open sources. There is no reason to suspect they would be any better than assessments from career academic specialists. At best, policymakers will waste time sorting through what appear to be the same as private sector and intelligence analyses. (This was a problem in the 1990s, when the CIA produced environmental analyses that replicated Environmental Protection Agency and academic research.) At worst, they will use intelligence only to influence public debates, turning analyses into political footballs in a way that invites politicization. In either case, the intelligence community’s reputation among policymakers will suffer.

Intelligence work is akin to private sector research in some senses, but in other ways it is unique. Unlike academia and journalism, which both exist to reveal knowledge, intelligence is fundamentally about stealing secrets. The intelligence profession has developed its own tradecraft for collecting and analyzing information that foreign actors do not want to share. If the intelligence community goes too far in the direction of collaboration, its peculiar tradecraft will atrophy.

And resources are finite. The intelligence community has a very large budget, but it covers a range of issues around the world, and serves many different customers. Because it covers so much ground, it runs the risk of going beyond its means. This is especially true for complex issues that demand years of professional training and experience. Avoiding the problem of analytical overstretch requires a kind of bureaucratic discipline, a willingness to say no to answering questions that are answered just as well in the private sector.

Instead, the community needs to provide the kind of information and insight that gives policymakers decision advantage. Doing so means focusing collection and analysis resources on a different set of questions, including the hidden consequences of transnational problems on foreign actors. These questions are admittedly narrow, but they are useful in weighing policy options. How to address a specific country’s response to climate change or infectious disease (or any other transnational issue) depends greatly on sensitive political assessments. Academic research can provide the vast majority of the underlying scientific data needed to shape a national approach to the problem. Intelligence provides details that help put that approach into practice.

What, for example, might a State Department desk officer for China want to know about climate change? A general understanding of the problem is helpful for context, of course, but she might have more specific questions for the intelligence community. What does Chinese leader Xi Jinping think about U.S. climate proposals? How has his private thinking changed over time? Who influences Xi on climate issues? Does he receive competing advice from different officials, from industrial officials, and from military officers? Is there a way that the United States can exploit those divisions in climate negotiations? Reliable answers to questions like these are not easy to find in the open. They come from different sources.

The comparative advantage of secret agencies is secret information. I suspect that this is true not just for policymakers who are looking for decision advantage, but also for agency recruiters on the lookout for talent. Part of the allure of intelligence is the ability to access information from unique sources, and to use it to inform the policy process. The reality will feel quite different if new intelligence professionals discover that their work is not terribly different from private sector research. This is a possible outcome if intelligence shifts its attention to transnational threats for which there is already a huge amount of public data. The kind of researchers whom the community needs to tackle these issues — climate scientists, epidemiologists, demographers, etc. — will have less reason to join and less reason to stay. Recent research points to troubling attrition rates among analysts, in part because of “a perceived loss of access and prestige.” The problem will become worse if policymakers see little difference between intelligence analysis and publicly available research.

Less Is More

None of this is to argue that the intelligence community should ignore transnational issues. The question is how it should address them. The current drift is toward broad open-source estimates; reorganization around new issues; more information sharing; and increased collaboration with the private sector. Cumulatively, these imply a radical change in how the intelligence community sees its role and how it performs its mission.

A different approach would be to scale back its effort on transnational issues, asking about particular questions where data is scarce. Rather than changing its organizational culture by embracing transparency, this would allow the community to offer an appealing value proposition. Rather than emphasizing collaboration with the private sector, it should strive for a sensible division of labor. The intelligence community has an opportunity to fill in knowledge gaps based on its ability to gain private information. This is more important than offering broad-brush treatments of issues like climate change and global health, where open-source data is abundant.

Others are likely to welcome a clearer distinction between intelligence and open research on transnational issues. International institutions have obvious reasons to distance themselves from the secret world. The World Health Organization, for instance, does not want to compromise its efforts by gaining a reputation for working hand in glove with intelligence services. In the past, it has been angered by alleged intelligence efforts that compromise its work. Such organizations rely on building public trust and cultivating a reputation for managing global problems rather than satisfying any given state’s parochial interest. The same is likely true for academic researchers who ferociously guard their intellectual independence, and who seek to cultivate a reputation for objectivity. Collaboration, from their perspective, carries its own set of risks.

The urge to think big about institutional change is understandable when the stakes are high. Calls for comprehensive reform have been around as long as the intelligence community itself, and they have typically followed the emergence of a new kind of danger. The push to build a permanent peacetime intelligence establishment was itself a response to the particular threat posed by the Soviet Union. In the aftermath of 9/11, critics called for sweeping reforms that would allow the intelligence community to adapt to non-state threats. Bipartisan agreement made these changes irresistible, and the community undertook its largest reorganization effort in decades. Today’s traumas, especially COVID-19 and climate change, are once again creating pressure to change how the intelligence community operates.

But perhaps, in this case, it should think small.

Joshua Rovner is an associate professor in the School of International Service at American University.

Image: NASA