A Lower Bar for the Cyber Czar

For years, critics of U.S. cyber security policy have called for more centralization. Government efforts are spread across many organizations, we are told, making effective coordination inefficient and ineffective. The sprawling constellation of interested parties makes it hard for policymakers to receive consistent advice, and it also inhibits oversight by spreading accountability thin. No real progress can occur without a clear whole-of-government effort, spearheaded by an official who can bear the brunt of presidential and congressional scrutiny. As Sen. Angus King put it, the government needs “one throat to choke.”

These arguments animated last year’s Cyberspace Solarium Commission, a congressionally mandated effort to outline a new approach to the domain. The commission settled on what it called “layered deterrence,” an amalgam of improved defenses and resilient networks, offensive operations to impose costs on adversaries, private sector outreach, and a renewed commitment to international norms. The complexity of this approach lent urgency to calls for more organizational centralization, and the commissioners called for the creation of a Senate-confirmed national cyber director. Last year they got their wish. At long last, the 2021 National Defense Authorization Act established the position of national cyber director to guide and coordinate cyber security policy.

Congress expects a lot of whoever gets the job. The National Defense Authorization Act instructs the director to coordinate national cyber strategy, develop a coordinated intergovernmental plan to respond to “cyberattacks and cyber campaigns of significant consequence,” ensure that offensive and defensive cyberspace operations are in sync with national policy, serve as the president’s principal cyber security adviser, and act as the chief liaison with industry, academia, and other private sector groups. On top of all this, the director will report to Congress on all aspects of cyber security, as well as “any new or emerging technologies that may affect national security, economic prosperity, or enforcing the rule of law.”

One would expect the national cyber director to head a large bureaucracy and enjoy substantial authorities, given the scope of these responsibilities. The National Defense Authorization Act allocates a staff of only 75, however, making it a miniscule presence compared to the agencies and bureaus whose work it is supposed to organize. A bureaucrat without a sizable bureaucratic constituency is inherently disadvantaged, and there is no reason to expect that this time will be different. Moreover, the national cyber director’s authorities are ambiguous at best, along with its relationship with senior National Security Council officials who provide similar if not overlapping functions. (Observers note that its first task will be figuring out its relationship with the National Security Council and the departments and agencies it is supposed to coordinate.) Although the office has the ability to review agency budgets, it can only offer recommendations to bring them in line with national cyber strategy, and the legislation explicitly declares that it is not “modifying any authority or responsibility, including any operational authority or responsibility of any head of a [f]ederal department or agency.” The national cyber director, in short, does not appear to have the powers it needs to fulfill its ambitious mandate.

The situation is reminiscent of the birth of the director of national intelligence in the George W. Bush administration. Like the national cyber director, the director of national intelligence was given the herculean task of synchronizing the disparate work of the various components making up the intelligence community. Previously, the director of central intelligence had this responsibility, while simultaneously leading the Central Intelligence Agency. Critics argued that doing both jobs was impractical, and called for a new director of national intelligence to oversee the whole community. This idea became law with the Intelligence Reform and Terrorist Prevention Act of 2004.

Unfortunately, the legislation was vague about the director of national intelligence’s actual powers. The office was meant to reduce organizational stovepipes and improve communication across the community. In practice, this meant exerting leverage over large intelligence agencies with long histories. And the biggest agencies resided within the Department of Defense, meaning that the director of national intelligence could face resistance from the Pentagon if it sought to make significant changes. This problem was apparent to intelligence observers during the legislative debate. The act made it clear to everyone else, stating that the new office could not “abrogate the statutory responsibilities” of the secretary of defense.

The director of national intelligence’s power, such as it was, came not from his authorities but through his relationship with the president. The White House could declare its expectation that agency heads were to treat the director of national intelligence as the hub of the community, and warn that failure to satisfy the director’s guidance would upset the president. The fact that the director of national intelligence was a Senate-confirmed Cabinet position made this warning plausible. But it was not clear why the president couldn’t have sent the same signal to the community regarding the director of central intelligence. If bureaucratic power was accumulated informally, it wasn’t clear why new legislation was required, or that it would help.

There is little evidence that the director of national intelligence has substantially improved intelligence performance since its creation. This is not surprising, given the chasm between its broad responsibilities and limited powers. The intelligence community made progress against al-Qaeda — the key problem the director was supposed to address — but most of the gains came before the office came into being. The functional work overseen by the director was already occurring elsewhere in the community, and there isn’t much reason to believe that changing organizational boundaries had any impact on their performance.

The situation today with respect to cyber security is not so different. Congress has created a new office with large tasks and limited authorities, and the success of the officeholder likely depends on the active and ongoing support of the president. And like the director of national intelligence, the national cyber director will face a daunting task of coordinating the operations and resources of large bureaucracies that have existing routines and organizational hierarchies. But in some ways the situation is even worse. The director of national intelligence focuses on a finite number of government institutions, all of which are involved in the production of secret knowledge. The national cyber director, by contrast, is also supposed to act as a key point of contact for the private sector, which largely owns and maintains the machines and networks that make up the domain.

The nature of cyberspace resists a unified approach. A fantastically complex set of interlocking technologies and institutions, it relies on a hodgepodge of engineers, firms, and governments, all of which participate in the care and feeding of the domain. Cyberspace also evolves as a result of the behavior of billions of users, whose preferences often determine how firms invest and how states respond. Security threats are likewise variable and changing, and as a result, efforts to maintain a consistent government approach will prove frustrating. This is true even if the trend toward centralization picks up steam in the Biden administration.

Why, then, are advocates so keen on a national cyber director? And why do they expect it to do so much?

Part of the reason is Congress’ longstanding impulse to reorganize. The institution does what it can, which in this case means legislating changes to government structure. Congress cannot legislate away the root causes of incoherent policy responses to cyberspace threats, because it cannot change the fundamental weirdness and sprawl of the domain. In addition, the push for a national cyber director follows a long tradition of trying to centralize intelligence (much of what goes on in cyberspace is an intelligence contest). Congress wants the national cyber director to manage knotty coordination problems across government, just as it pushed for a director of national intelligence to solve the coordination problems in the intelligence community.

Centralization appeals to common sense, but it works best as an organizational solution to clearly defined and unchanging problems. In these cases a central authority is useful for describing objectives, distributing information, organizing roles and missions, and monitoring progress. But cyber security is neither clearly defined nor unchanging. It is the opposite. Threats include everything from espionage and influence operations to physical sabotage against infrastructure, and operations mutate as intruders seek clever new ways to infiltrate target networks. Organizations with specific capabilities and authorities do not need direction from a czar, they need autonomy to develop responses to these various threats. The calls for centralization are understandable, but the peculiar characteristics of cyberspace actually demand a decentralized solution. The upshot is that the first national cyber director will start work on the basis of a misguided strategic premise, in addition to facing an unenviable bureaucratic position. We should set our expectations accordingly.

What should we reasonably expect? Although the national cyber director will struggle to craft and coordinate a government strategy, it may prove more successful coordinating interagency efforts with the private sector. The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency performed this role well before and during the election. The national cyber director can build on that experience and foster public-private relationships, encouraging durable threat information sharing and easing the movement of cyber security professionals in and out of government. This last point is particularly important, given the enduring problem of finding talent and keeping it.

A good starting point might be the investigation into the SolarWinds operation, a foreign intrusion into private firms and government networks via widely disseminated network management software. Assessing the causes and consequence will require candid conversations among industry and government leaders. A new national cyber director with experience in both worlds may be in a particularly good position to facilitate those discussions. (According to one report, the Biden administration has chosen Jen Easterly, an Obama administration veteran currently working as head of resilience at Morgan Stanley.) This, in turn, could prove to be a springboard to more durable cooperation.

It might sound trite, but the public-private nexus is vital to long-term cyber security. Because the state does not control the domain, it cannot succeed without private sector support. Coordinating efforts is difficult, however, because the interested parties have very different interests and incentives. States want security, corporations seek profit, and advocacy groups strive to protect civil liberties while providing expanding access to underrepresented groups. Navigating these complex and fraught issues will be a full-time job for the national cyber director, especially given its small staff. Asking it to do much more will set the stage for failure.

Joshua Rovner is an associate professor in the School of International Service at American University. He served as scholar-in-residence at the National Security Agency and U.S. Cyber Command in 2018 and 2019. The views here are his alone.

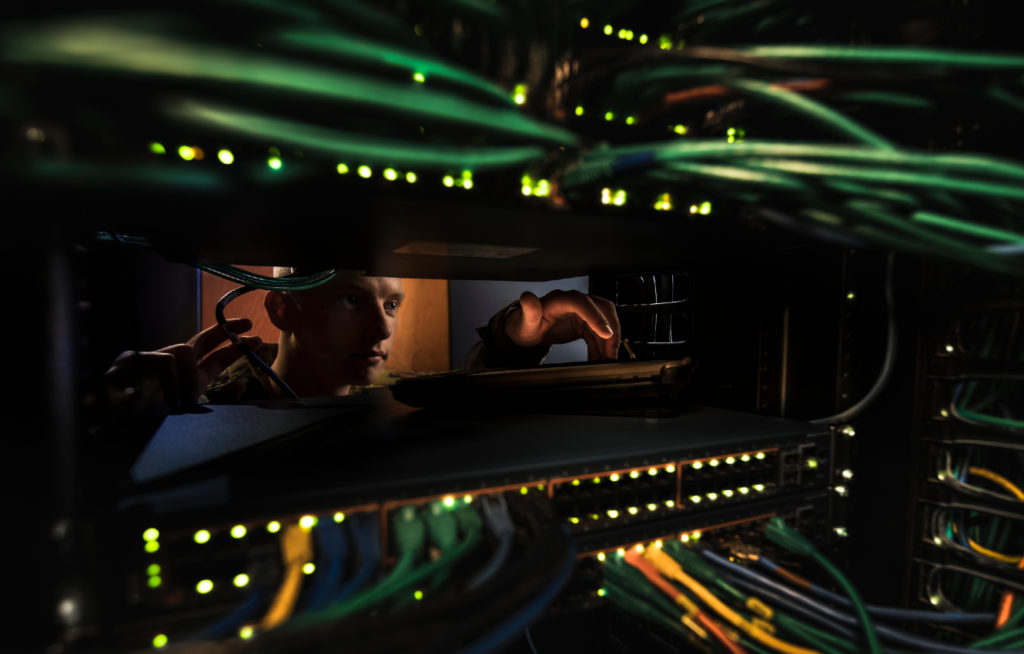

Image: U.S. Air National Guard (Photo by Staff Sgt. Jon Alderman)