Garrison vs. Wilson: The Cabinet Resignation that Shook a Nation on the Brink of Crisis

Principled, high-profile resignations by high-ranking cabinet officials are relatively rare in American history. Woodrow Wilson experienced two over disagreements about his European war policy: those of his secretary of state, William Jennings Bryan, in 1915 and his secretary of war, Lindley Garrison in 1916. Bryan is far better known today and was in his own lifetime as well, but Garrison’s shocking resignation hit Washington like a bombshell not unlike that of Secretary of Defense James Mattis last week. It also had a much more lasting impact on American military and defense policy than anyone could have imagined at the time.

Like the secretary of the navy, Josephus Daniels, Garrison had little familiarity with the military when he was named secretary of war in 1913. A native of Camden, New Jersey, Garrison had come to Wilson’s attention while serving as vice-chancellor of the state during Wilson’s tenure as governor there. Known as a progressive reformer and an efficient state administrator, Garrison nevertheless came to office as Wilson had: completely unprepared for a major foreign policy crisis.

He got one in the war that began in Europe in the summer of 1914. That war soon proved to both Daniels and Garrison that the U.S. military was woefully unprepared for modern warfare. For Daniels and the Navy he directed, the problem seemed relatively straightforward. The Navy would need new ships and men to crew them. For the prohibitionist Daniels, it also meant getting alcohol off of the Navy’s ships. Daniels got what he wanted, both in banning alcohol (the phrase “cup of Joe” may be a sarcastic reference to the coffee sailors drank in place of wine, beer, and spirits) and in getting large Congressional appropriations for new warships. As Daniels and his assistant secretary, Franklin D. Roosevelt, discovered, the Navy was an easier sell than the Army because fleets protect shores and commerce, project power, and bring jobs to local constituencies.

Selling the Army was far more complicated in 1914 and 1915. Supporters of Army reform always had a difficult time answering the question of what the nation really intended to do with tens of thousands of additional soldiers. Even after voting for war, Virginia Sen. Thomas Martin asked a startled Army officer “Good Lord! You’re not going to send soldiers over there, are you?”

If Army reform was a tough sell at the start of a war, Garrison found it almost impossible in peacetime. He saw the military problem clearly enough. He knew that the U.S. Army of 1915 could not possibly fight the European war within its National Guard/militia structure. The Army had, in effect, 49 commanders-in-chief with 49 systems of training and 49 sets of equipment. The depths of this problem became evident in response to the expedition to track down Pancho Villa. One governor, who opposed the expedition, dissolved his state’s militia rather than see it dispatched to Mexico. Another governor decided to send prison parolees.

To Garrison and his supporters, such a system seemed hopelessly antiquated. One Iowa newspaper called the American reliance on militia “an 18th century idea fit for a pioneer country that had never heard of railroads, steamships, or percussion caps.” To send it into the battlefields of Europe would be to condemn young American men to futile sacrifices. The Lusitania crisis had shown Americans that they might not be able to remain in their state of profitable neutrality forever. They had to get ready.

Garrison was certainly not alone in seeing the problem, although no consensus formed about the right solution. Former President Theodore Roosevelt and Gen. Leonard Wood pressed for universal military training and conscription on the European model. They had some support in the northeast but the idea was unpopular in the rural west and south. It would have represented the first time that the United States had introduced conscription in peacetime. To many Americans it seemed a dangerous step toward the very militarism that many believed had caused the war in Europe in the first place.

Bryan, state governors, and most members of the House of Representatives wanted a large volunteer army based in the militias and national guards. Such a force, they believed, would deter and prevent foreign powers from trying to bully the United States, but specifically because of its decentralization, it would be difficult for a president like Wilson to deploy forces outside the nation’s borders (as he later did in Mexico and Haiti). In the event of a genuine national crisis, the nation could raise forces as it had in 1898, by signing large numbers of short-term volunteers. They saw in their ideas a reflection of the Swiss system, which kept the nation safe from invasion but inoculated it from the domestic dangers of militarism.

Military professionals were aghast at such ideas, seeing them as wholly inappropriate for a great power in the modern world. An Army War College study proposed the formation of a “peace army” of 1,134,000 men, including an increase in the coastal artillery branch and 60,000 men for a proposed Harbor Defense Force. The New York Tribune praised the plan as a method by which “the country is always prepared but on a peace basis.” Still, even the Army knew that the numbers were far too big for Congress to fund, and that a force that large would raise difficult questions.

Garrison agreed with the Army War College’s diagnosis of the problem, but he pushed a different solution: an army based on progressive ideas of centralization, efficiency, and industrial methods of scale and scope. In late 1915 Garrison introduced the Continental Army Plan, which argued for eliminating the Guard in favor of a single national army directed by and answerable to officials in Washington. Garrison’s Continental Army Plan had much to recommend it on a military level, but it ran into two brick walls of the American political system: racism and federalism.

In order to find the 500,000 soldiers Garrison believed the plan would need, he argued for recruiting soldiers without regard to race. The African-American press rallied to the idea, seeing in it a way to prove the patriotism of black Americans and undercut the Jim Crow ideology of the Wilson years. Wilson, state governors, and most members of the House pushed back, especially in defense of segregation. Virginia’s James Hay (chairman of the House Armed Services Committee) and Mississippi’s James K. Vardaman warned that once African-Americans were allowed to join, whites would refuse to serve, leaving the nation’s defense in the hands of a minority they deeply mistrusted. Northerners, too, raised concerns, with one New York politician opposing the Continental Army Plan because it might lead to giving African-Americans the right to vote nationwide. Governors feared a loss of power to the president, and most whites feared a shift in the nation’s racial power balance. Garrison did his best to argue that such concerns had to take a back seat to the exigencies of national defense, but he failed.

Wilson’s willingness to support the resulting political compromise, the National Defense Act of 1916, infuriated Garrison. The act raised the Regular Army to a theoretical ceiling of 140,000 men, but it also raised the size of the National Guard from 130,000 to a theoretical ceiling of 425,000. A Reserve Officers Training Corps was created to train its future leaders on college campuses. The Guard became subject to federalization in the event of a national emergency and it received federal dollars to modernize and standardize its equipment and training. Those dollars came at the expense of reforms Garrison believed the active-duty Army badly needed. The Act did nothing to address segregation at either the national or the state level.

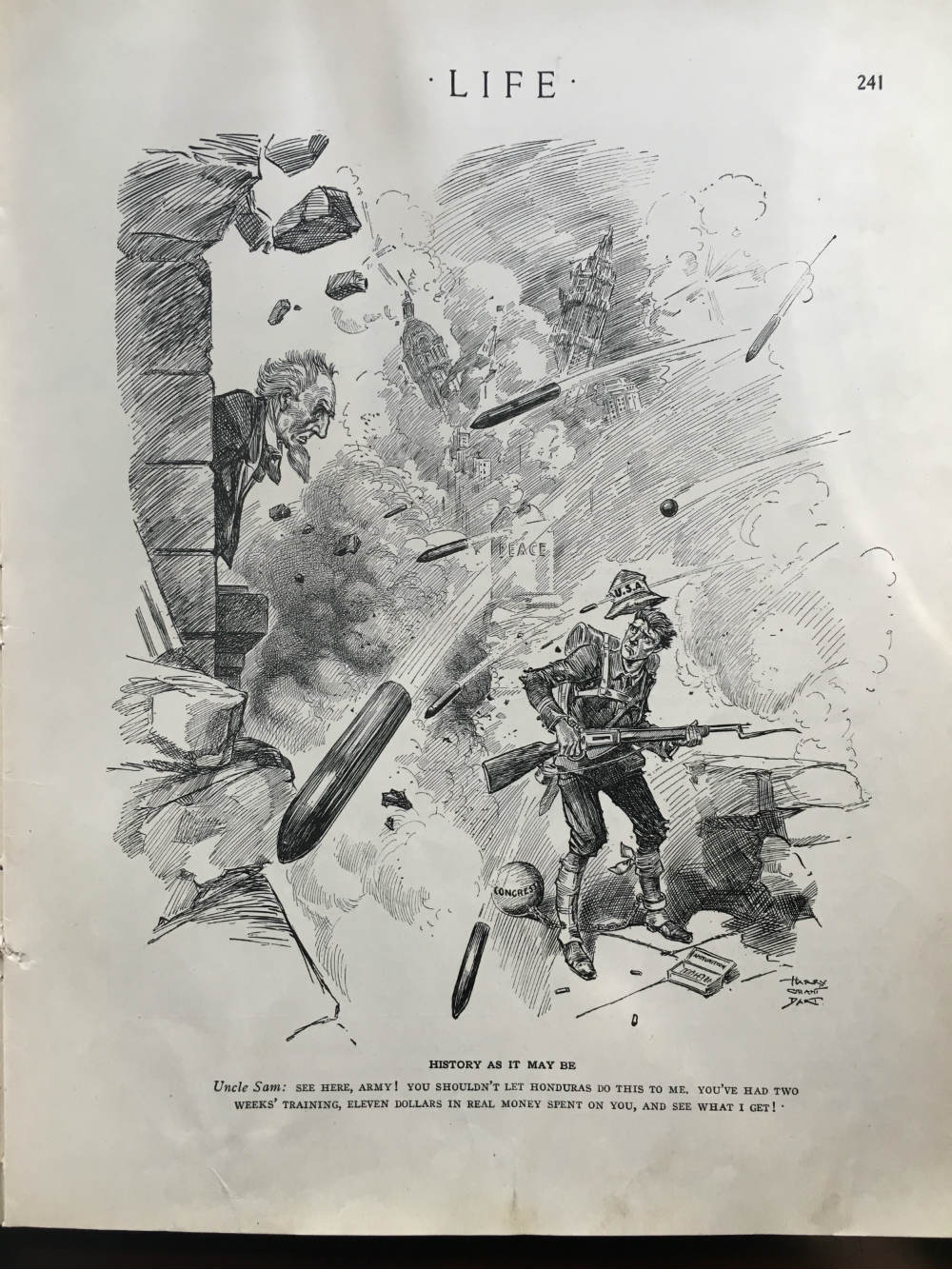

Theodore Roosevelt blasted the law, arguing that it was too little too late to prepare the nation for the coming war. A cartoon in Life magazine showed an American soldier running away from a battle with an iron ball labeled “Congress” tied to his feet. Uncle Sam yells at him “See here, Army! You shouldn’t let Honduras do this to me. You’ve had two weeks’ training, eleven dollars in real money spent on you, and see what I get!” An empty ammunition box sits broken on the ground, symbolic of Congressional parsimony. The Navy, as expected, did better, getting $315 million for new ships, well more than half of the bill’s total expenditures.

The system that the 1916 National Defense Act created was the one the United States used, for better or worse, in both world wars. The vast majority of America’s soldiers fought World War I as part of state National Guard units called up for federal emergency. The system, updated and reformed over the years, remains the backbone of the Army’s Total Force concept. Desegregation would have to wait until 1948.

The National Defense Act destroyed Garrison’s relationship with Wilson, although the president was slow to realize it. On February 10, 1916 Garrison sent Wilson a letter soon published in newspapers (especially African-American newspapers) nationwide. It read in part: “It is evident that we hopelessly disagree upon what I conceive to be fundamental principles.” A stunned Wilson replaced him with Cleveland mayor Newton Baker, a self-proclaimed pacifist who had no interest at all in the Continental Army Plan.

Garrison’s resignation removed one of the most respected and trusted members from the Wilson cabinet at a time of international tension, war, and uncertainty. He largely faded from public view because of his desire not to be seen as interfering with the 1916 presidential election, but a century later the debate he helped to spark continues to shape the U.S. Army through the relationship with the National Guard and the ROTC programs introduced in 1916 The debate itself is a reminder of the central importance of domestic politics to national defense as well as the long-term impact of ideas and the politicians who develop them.

Michael S. Neiberg is Chair of War Studies at the U.S. Army War College. His book, The Path to War (Oxford University Press, 2016) is an analysis of American reactions to the World War, 1914-1917. He is also the author of A Concise History of the Treaty of Versailles (Oxford University Press, 2017). The views expressed here are those of the author, not the U.S. government or any part thereof.