Amusing Archival Discoveries from the Cold War

Declassified documents offer a rare window into the decision-making process surrounding some of the most consequential events on record. They allow today’s researchers to travel back in time and become flies on the wall as senior officials grapple (often aloud) with the benefits and costs of important policy decisions.

Archival research has another perk: occasional humor. After locating an amusing document on a recent trip to the John F. Kennedy Library, I decided to see what fellow scholars had come across in the course of their research with an eye toward the Cold War period.

The responses did not disappoint. They appear below in chronological order. Hyperlinks to quotes are included wherever possible. In cases where there is no hyperlink, a picture of the document containing the quote can be obtained via the contributor.

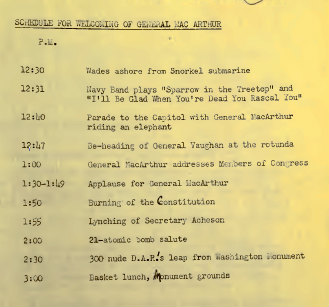

After Harry Truman fired Gen. Douglas McArthur in the midst of the Korean War in 1951, relations between the two men reached an entirely new level of hostility. The passage, written by one of Truman’s advisor in April 1951, is a satirical schedule of McArthur’s return from Korea. The document is contained in George Elsey’s papers. (Note: Gen. Harry H. Vaughan was a close advisor to Truman).

Elizabeth Saunders (@ProfSaunders) is an Associate Professor of Political Science at George Washington University. She is the author of Leaders at War: How Presidents Shape Military Intervention (Cornell University Press, 2011).

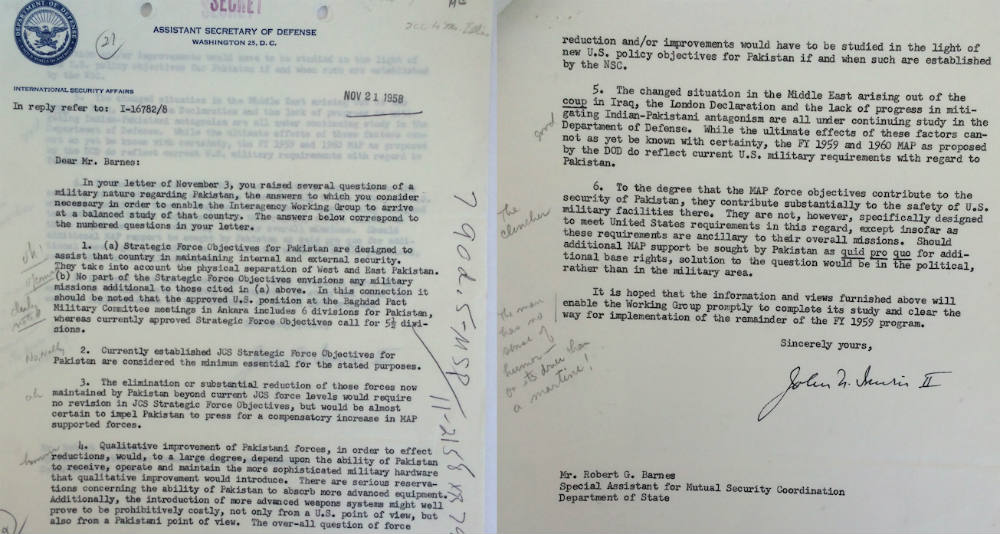

State vs. Defense

“This man has no sense of humor – or it’s drier than a martini!”

Robert Barnes, of the State Department, wrote this note in the margins of a letter he received from the Department of Defense. In an earlier letter, Barnes had asked Defense for information about the U.S. military assistance program for Pakistan. The response he received was dry, blunt, and not particularly helpful, explaining that aid to Pakistan was for political, rather than military reasons. This rationale didn’t come as a surprise to Barnes, whose sarcasm is reflected in the various notes he wrote in the margins, including “oh! of course” and “no, really.” Frustrated by the lack of active cooperation from the Department of Defense, he wrote a comment at the end of the letter capturing the general divide and tensions that existed between the Departments of Defense and State where military assistance was concerned: “This man has no sense of humor — or it’s drier than a martini.” The document is located at the U.S. National Archives.

Jennifer Spindel (@jsspindel) is an Assistant Professor in the Department of International and Area Studies at the University of Oklahoma (beginning August 2018).

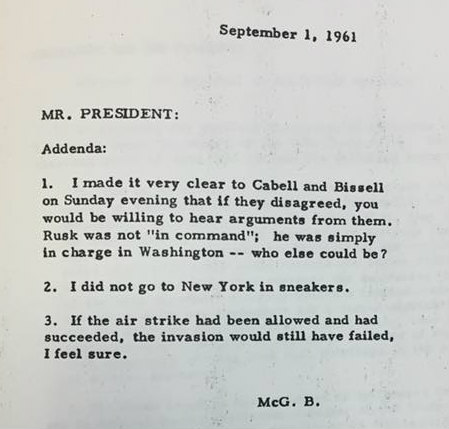

An amusing remark appeared as one of several addenda to a memo McGeorge Bundy wrote to President John F. Kennedy on September 1, 1961, a little less than five months after the Bay of Pigs invasion — a covert operation to overthrow Fidel Castro in Cuba — failed disastrously. “I did not go to New York in sneakers,” Bundy insisted, in between two more serious comments, one about who was “in command” at the time of the operation and another about his feeling that the venture still would have failed had Kennedy had not called off air strikes to assist the Cuban exiles at the last minute. The document is located at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library.

Michael Poznansky (@m_poznansky) is Assistant Professor in the Graduate School of Public and International Affairs at the University of Pittsburgh. His current book project is entitled The Politics of Secret Interventions: Covert Action and International Law.

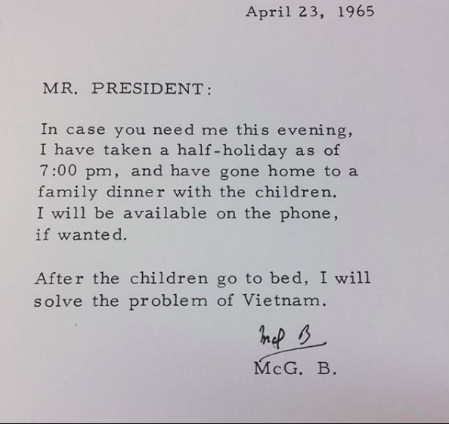

Escalation in Our Time, But After Supper

This is a letter from McGeorge Bundy to President Lyndon Johnson, written on April 23, 1965, less than two months after the start of what would become a three-year bombing campaign of North Vietnam and a significant escalation of American involvement in the Vietnam War. The document is located in the Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library.

Erik Lin-Greenberg is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Political Science at Columbia University. Starting in Fall 2018, he will be a Predoctoral Fellow at Stanford University’s Center for International Security and Cooperation.

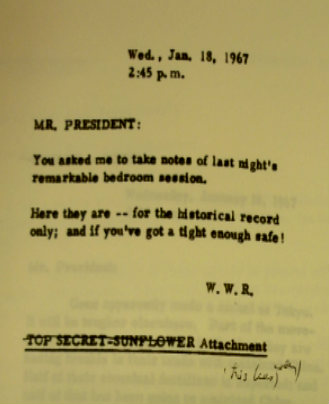

Walt W. Rostow, the National Security Advisor at the time, providing Lyndon Johnson with a summary of a top-secret conversation they had with Sens. Mansfield and Dirksen in the president’s bedroom on January 17, 1967. The purpose of the meeting was to discuss the possibility of negotiating an end to the Vietnam War through direct talks with Hanoi. Before telling them about the venture, Johnson swore both men to secrecy given the sensitive nature of the controversial negotiations. According to Rostow’s notes, “Senator Mansfield sat on a chair in the far corner of the room; Senator Dirksen sat on the President’s bed. The President was standing, in stocking feet, as he completed dressing for dinner.” The document is available through the Foreign Relations of the United States series.

Andrew J. Gawthorpe (@andygawt) is Lecturer in History and International Studies at Leiden University’s Institute for History. He is author of To Build as Well as Destroy: American Nation Building in South Vietnam (Cornell University Press, 2018).

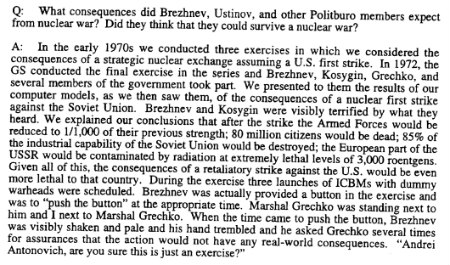

This anecdote is one of innumerable important insights from a series of interviews with Soviet generals and nuclear planners secretly conducted by the Department of Defense contractor BND Corporation at the end of the Cold War. This particular one was with Gen. Andrian A. Danilevich, a senior Soviet military officer. It shows that Leonid Brezhnev, the leader of America’s adversary, also had trepidation about destroying the world — and apprehension that he could begin a nuclear war by accident (e.g. pressing a fake button). The text is available via the National Security Archive.

Nate Jones (@NSANate) is the Director of the FOIA Project at the National Security Archive and has written about the Able Archer 83 nuclear war scare.

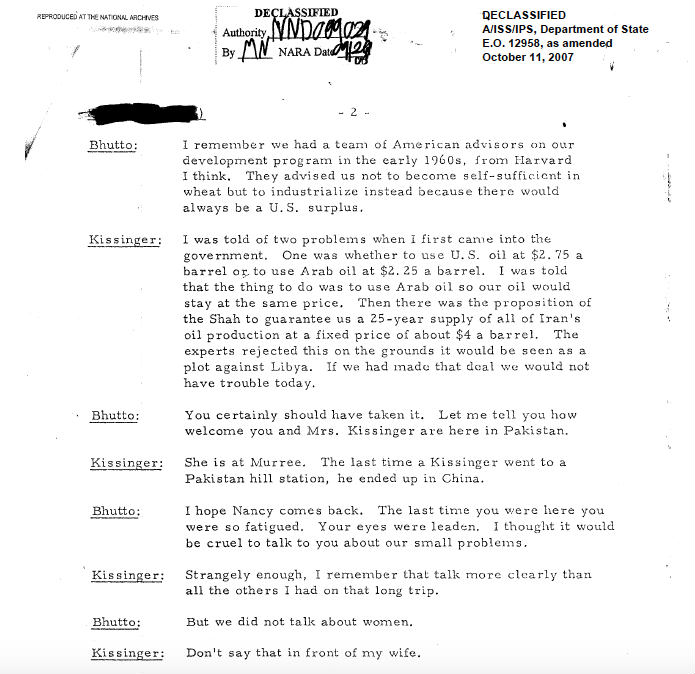

A conversation between Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and the Prime Minister of Pakistan Zulfikar Ali Bhutto on October 31, 1974. The discussion covered a variety of bilateral issues including Pakistan’s desire for conventional arms sales from the U.S. after India’s first nuclear test. In March 1975, the Ford administration lifted the arms embargo on Pakistan. The document is available through the Foreign Relations of the United States series.

Nicholas Miller (@Nick_L_Miller) is Assistant Professor in the Department of Government at Dartmouth College. He is the author of Stopping the Bomb: The Sources and Effectiveness of U.S. Nonproliferation Policy (Cornell University Press, 2018).

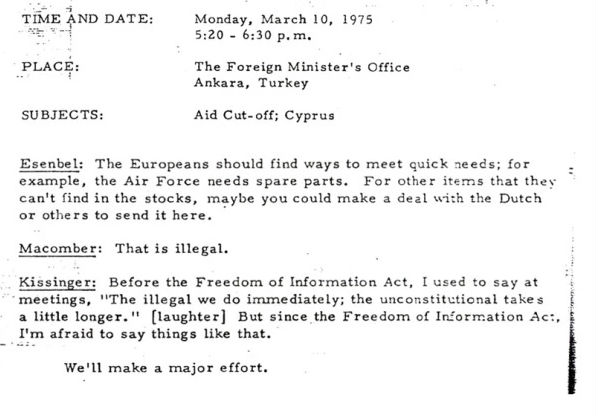

Kissinger Says the Darndest Things

Kissinger was speaking to the Turkish foreign minister in March 1975 about the arms embargo the U.S. placed on Turkey after their invasion of Cyprus in 1974. The embargo was imposed by Congress despite objections from the Ford administration and Kissinger was looking for ways to help the Turks out. He clearly felt the Freedom of Information Act had cramped his style. The embargo was eventually lifted a little over three years later at the urging of Jimmy Carter. The document is available through the National Security Archive.

James Goldgeier (@JimGoldgeier) is Professor of International Relations at American University and Visiting Senior Fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations.

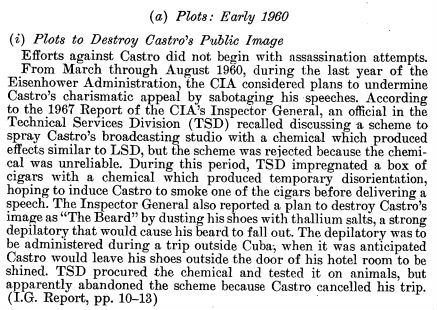

His Beard Was the Source of Communist Power

A ploy related to Fidel Castro’s beard was revealed in a report entitled “Alleged Assassination Plots Involving Foreign Leaders,” authored by the Senate’s Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities — a.k.a. the Church Committee — on November 20, 1975. The Church Committee was created in early 1975 to investigate alleged abuses by the U.S. intelligence community. They issued their final report on April 29, 1976. These various reports are available through the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence’s website.

Jeff Colgan (@JeffDColgan) is the Richard Holbrooke Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science and Watson Institute for Public and International Affairs at Brown University. He is the author of Petro-Aggression: When Oil Causes War (Cambridge University Press, 2013).

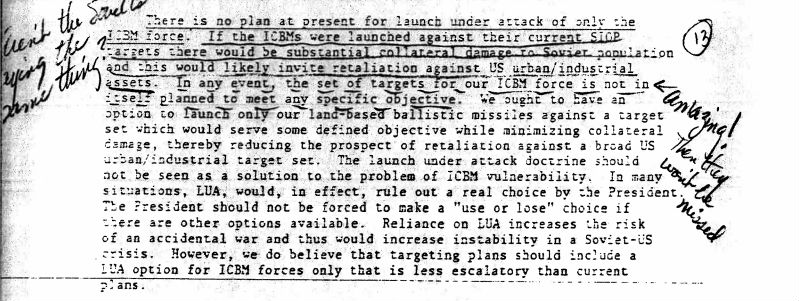

Nuclear Policy Targeting Review: “In any event, the set of targets for our ICBM force is not in itself planned to meet any specific objective.”

Arms Control and Disarmament Official: “Amazing! Then they won’t be missed.”

An indirect exchange of bureaucratic ire took place in the pages of the 1978 Nuclear Targeting Policy Review, a study from the Carter administration examining the capabilities the United States needed to deter a nuclear attack by the Soviet Union. The Review stated, “In any event, the set of targets for our ICBM force is not in itself planned to meet any specific objective.” In the margin, another official wrote, “Amazing! Then they won’t be missed.” This sardonic comment on the utility these ICBMs captures the political battles over disarmament during the Carter administration. The document is available through the National Security Archive.

Stacie Goddard (@segoddard) is Professor of Political Science at Wellesley College. She is the author of When Right Makes Might: Rising Powers and World Order (Cornell University Press, 2018). Colleen Larkin is a PhD student in the Political Science Department at Columbia University. They are currently researching the role of precision and ethics in nuclear strategy.

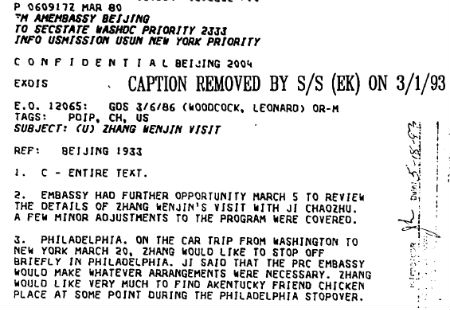

Communist China and Kentucky Fried Chicken

This March 1980 cable is from the Embassy in Beijing to Washington is about an upcoming visit by then-Deputy Foreign Minister Zhang Wenjin. Apparently, Zhang was to travel from Washington to New York City by car and had a specific culinary request. The document is available through the National Security Archive.

David Beitelman (@SunCatapult) received his PhD from Dalhousie University, where he is also a Research Fellow at the Centre for the Study of Security and Development. His dissertation is titled “Strategic Trust: Re-thinking U.S.-China Military Relations.”

Love Those Sanctions

“The USA has had a strong inclination towards the imposition of sanctions since the Boston Tea Party.”

After the imposition of martial law in Poland in December 1981, the Reagan administration introduced a series of sanctions on the Soviet Union, much to the chagrin of Washington’s transatlantic partners. In this January 1982 meeting with Alexander Haig, Helmut Schmidt laments the U.S. propensity for sanctions, dating back to the Boston Tea Party. Schmidt’s arguments were two-fold (and strikingly familiar to present-day observers of international affairs): Europe was far more dependent on trade with the Soviet Union than the United States and would bear the brunt of the sanctions. To make matters worse, the Reagan administration had imposed these sanctions without consulting its NATO allies in advance. The parallels to the current administration’s approach are hard to miss and a reminder that anxieties about American unilateral action and a lack of consultation have long plagued transatlantic relations. The document is from Akten zur Auswärtigen Politik der Bundesrepublik Deutschland 1982.

Susan Colbourn (@secolbourn) recently completed her PhD in History at the University of Toronto and will be a Henry Chauncey Jr. ’57 Postdoctoral Fellow at Yale University’s International Security Studies for the 2018-2019 academic year. She is currently completing a book manuscript on NATO and the Euromissiles Crisis.

Too Much Lenin, Not Enough Time

“Do we really need these quotes from Lenin?”

By the end of Leonid Brezhnev’s life, ideology in the Soviet Union seemed to be on the wane. A trenchant editorial suggestion by leading ideologue Vadim Zagladin about a speech being written for delivery at a Central Committee Plenum in the spring of 1982 hints at how pervasive this might have been even within the Kremlin itself. He asked, “Do we really need these quotes from Lenin?” The speeches of the era make clear that suggestions not to invoke Lenin’s authority are few and far between — references to him were virtually omnipresent. Zagladin’s suggestion to do less of this is a rare one, making his comment particularly unusual; but it is not out of step with some other officials’ remarks from the time about the cynical deployment of ideological tropes. This document is located in the Russian State Archive of Contemporary History. Photographs of documents are not permitted there, so this is a photograph of Simon’s notes from his visit to the archive.

Simon Miles, a diplomatic historian, is an Assistant Professor at Duke University’s Sanford School of Public Policy. His current book project is Engaging the ‘Evil Empire’: The Transformation of Superpower Relations, 1979–1985.

This letter was discovered during research into the “yellow rain” incidents, in which chemical weapons were used in Southeast Asian Communist countries. Deputy Director of Central Intelligence John McMahon writes, “Thank you for the article describing your investigation of bee feces.” This was a reply on October 8, 1985 to Dr. Matthew Meselson, who suggested the yellow rain was a natural phenomenon and that the toxins were related to bee feces. The document is located at the CIA’s Electronic Reading Room.

Veli-Pekka Kivimäki (@vpkivimaki) is a researcher and lecturer on intelligence, based in Finland. He runs the blog Open INT, which focuses on intelligence-related archive material and open source intelligence.