Join War on the Rocks and gain access to content trusted by policymakers, military leaders, and strategic thinkers worldwide.

The Battle of Antietam on Sept. 17, 1862, remains the deadliest one-day battle in American military history with nearly 23,000 casualties, including over 3,600 deaths. While the monument observing the “High Water Mark of the Rebellion” stands at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, the true high tide of the Confederacy arguably came on a late summer day at Sharpsburg, Maryland, beside the swiftly flowing Antietam Creek. The U.S. Army’s victory there provided an opportunity to recast the American Civil War beyond just preserving the Union to one of emancipation — and eventually abolition of slavery. Although the war would drag on for almost another three years, the Confederacy would face increasingly long strategic odds after the defeat at Antietam.

The battle reminds military and defense planners of the challenges of translating tactical action into strategic gain, balancing risk and reward, and implementing — not just observing — hard lessons.

A Confederate Rising Tide

The Civil War started slowly in 1861, but by May 1862, the United States clearly had the momentum. In the west, the U.S. Army had advanced deep into the Cumberland River and Tennessee River valleys. In the east, Maj. Gen. George McClellan and the U.S. Army of the Potomac’s Peninsula Campaign had pushed the Confederate Army of the Potomac, commanded by Gen. Joseph E. Johnston, to the outskirts of Richmond, the rebel capital. When Johnston was wounded on June 1, Gen. Robert E. Lee took command and then unleashed the renamed Army of Northern Virginia in the Seven Days Battles from June 25 to July 1. Unnerved by the ferocity of the fighting, McClellan retreated and eventually withdrew by mid-August. With McClellan’s defeat, U.S. President Abraham Lincoln raised the U.S. Army of Virginia, commanded by Maj. Gen. John Pope, to defend Washington, D.C. The tide had begun to shift.

Meanwhile, Lincoln was ready to move beyond the policy of conciliation toward the Confederacy as it was proving to be an inadequate theory of victory. Seeing how the rebellion drew strength from its enslaved population, Lincoln floated a draft proclamation for emancipation, which would free all enslaved persons in rebel-held areas, to his cabinet on July 22. Receiving a tepid response, Secretary of State William Seward advised Lincoln to wait until after a battle victory to issue the proclamation from a position of strength.

At the same time, Lee prepared to strike Pope, whose forces were outside the safety of the Union defenses surrounding Washington. Lee and Confederate President Jefferson Davis envisioned victory through the offense, emphasizing a decisive battle of annihilation to destroy the Army of the Potomac and undermine the Union’s will to continue the war. This approach acknowledged that the Confederacy lacked the manpower to destroy the armies of the United States or the lasting material power to exhaust the United States in a protracted war. Shocking the American public before the 1862 midterm elections presented a golden opportunity to secure victory.

Lee dispatched Maj. Gen. “Stonewall” Jackson’s forces to cut Pope’s lines of communications at Manassas Junction, Virginia, forcing him to withdraw from his Rappahannock River defensive line in central Virginia north to Manassas. He then sent Maj. Gen. James Longstreet to strike Pope’s left flank. The ensuing Second Battle of Bull Run in Manassas on Aug. 28-30 resulted in Confederate victory. Still, Pope’s defeated army withdrew to Washington before Lee could annihilate it. To lure the U.S. Army back out, Lee initiated a new campaign on Sept. 3, writing Davis that “[t]he present seems to be the most propitious time since the commencement of the war for the Confederate Army to enter Maryland.” The tide was rising.

Lee initially planned to live off the fertile land in Maryland but quickly discovered that he would instead need to reestablish a line of communication through the Shenandoah Valley, requiring that he eliminate the U.S. Army garrisons at Martinsburg and Harpers Ferry in Union-held western Virginia, that sat astride this line. Accordingly, on Sept. 9, he issued Special Orders 191, splitting his forces into four separate columns. Three under Jackson’s command with a total of six divisions would converge on Harpers Ferry, while a fourth column of three divisions under Longstreet would be sent forward to Hagerstown, Maryland to secure the logistics trains. Lee wrongly assumed the U.S. forces would abandon their garrisons in the face of a numerically superior enemy, allowing the Harpers Ferry operation to end by Sept. 13 and permitting Lee to reconsolidate at Hagerstown to continue the campaign. He also assumed that McClellan would be slow to close on Lee’s army.

However, the Harpers Ferry garrison was ordered to defend “to the latest moment” and the Martinsburg garrison joined it, leaving Jackson to face a bolstered force of 13,000 defenders. Additionally, McClellan had reconstituted and maneuvered an 83,000-strong army out from Washington faster than Lee expected. Fortuitously, McClellan’s soldiers found a copy of Special Orders 191 on Sept. 13 — revealing that Lee was dispersed and vulnerable — spurring McClellan to seek battle.

On Sept. 14, McClellan clashed with Lee at the Battle of South Mountain at Fox’s, Turner’s, and Crampton’s Gaps to the west of Frederick, Maryland, potentially isolating two of Lee’s divisions (Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws’ and Maj. Gen. Richard Anderson’s) across the Potomac River in Maryland, north of Harpers Ferry. Lee initially decided to end the campaign and withdraw from Maryland back into the safety of Virginia. However, once Lee learned that Crampton’s Gap had fallen to McClellan, Lee then paused the withdrawal and halted at Sharpsburg to protect his two divisions by threatening McClellan’s advance.

When Lee learned midday on Sept. 15 that Harpers Ferry had finally surrendered — removing the immediate threat to his force — he reversed course and decided to concentrate his entire army at Sharpsburg to salvage the Maryland campaign. If successful in his defense, he could use the Hagerstown Pike from Sharpsburg to turn McClellan’s flank to strike a decisive blow and achieve his ultimate aim to undermine Northern will. If not, he could still cross into Virginia and then re-enter Maryland at Williamsport to the northwest.

The stage was thus set for a battle that would redefine the war’s trajectory.

Blood on Union Soil

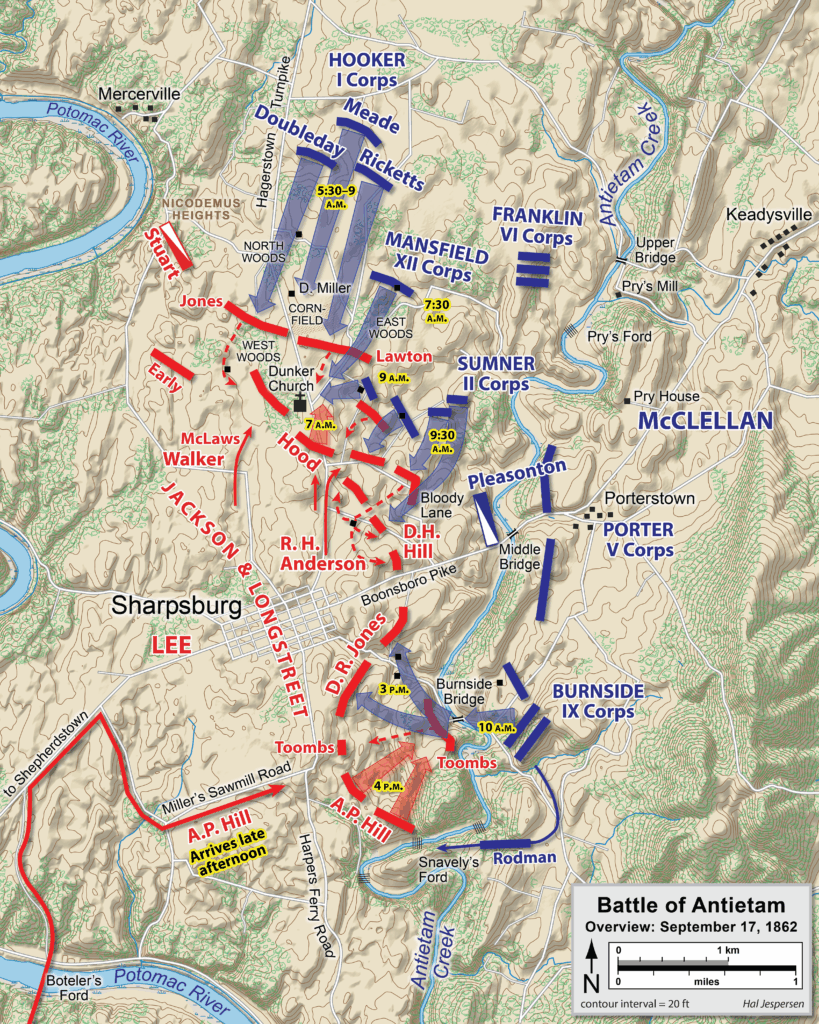

While defending at Sharpsburg dangerously placed Lee’s back to a major river, complicating a retreat, it also provided interior lines and significant and defensible high ground. Lee’s position also took advantage of Antietam Creek to his front, which impeded McClellan’s advance. Lee chose to defend at the creek on his right flank and center — covering two of three bridges spanning the creek — while defending away from the creek on the left. To protect his open left flank, he deployed Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart, his trusted cavalry commander, to loosely screen between Hagerstown Pike and the Potomac. Lee had set a potential trap here, daring McClellan to split his forces across the creek, which could subsequently be flanked by a Confederate mobile reserve force.

Although nipping at Lee’s heels now, McClellan chose to wait 24 hours for more forces to arrive before sending Maj. Gen. Joe Hooker’s I Corps on Sept. 16 across the undefended Upper Bridge to the north to scout a potential flank attack. Hooker pushed forward until skirmishing broke out and darkness arrived, halting in the North Woods. Meanwhile, Jackson’s wing, minus Maj. Gen. A.P. Hill’s division that was implementing the Harpers Ferry surrender, flowed into Sharpsburg, boosting Lee’s force from 25,000 to 35,000 troops. Lee kept three of his eight divisions in reserve while the remaining divisions formed a non-contiguous line by occupying key terrain north and east of Sharpsburg.

The battle began around 6 a.m. at the northern sector of the battlefield, with Hooker’s corps advancing toward Jackson’s forces through an unharvested cornfield. The weight of the attack pushed Jackson’s forces back. A counterattack by Brig. Gen. John Hood’s division recaptured the cornfield but then collided with Maj. Gen. Joseph Mansfield’s XII Corps advancing from the East Woods. Mansfield’s first division (led by Brig. Gen. Alpheus Williams) made no progress, but his next one (Brig. Gen. George Greene’s) broke the Confederate line, advancing to the Dunker Church and forcing Hood into the West Woods. Maj. Gen. Edwin Sumner’s II Corps then joined the fight, with his first division (Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick’s) attacking into the West Woods. In response, a crushing flank attack by elements of multiple Confederate divisions bloodied Sedgwick’s division, ending the fighting in the northern sector. Four hours of fighting produced 8,200 casualties in the Cornfield and another 4,300 in the West Woods.

Fighting in the center commenced around 9 a.m. as Sumner’s second division (led by Brig. Gen. William French) pushed toward Longstreet’s sector, where he met Maj. Gen. D.H. Hill’s division in a deeply worn, sunken lane. French’s piecemeal brigade attacks were unsuccessful, but the arrival of Sumner’s last division (Maj. Gen. Israel Richardson’s) allowed the U.S. Army to flank the reinforced Confederates and drove them from their “Bloody Lane” position. Despite having the initiative, Sumner halted Maj. Gen. William Franklin’s VI Corps, missing an opportunity to crack Lee’s lines and inflict serious damage. After four hours the fighting in the center stopped, with both sides suffering a total of 5,400 casualties.

To the south, Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside’s IX Corps prepared to assault the Confederates (Brig. Gen John Jones’ division) across the Lower Bridge, finally initiating the attack at 10 a.m. A pugnacious defense by the rebels — who enjoyed the advantage of steep high ground surrounding a narrow bridge that funneled the attackers — combined with a lack of reconnaissance and piecemeal attacks by Burnside allowed the Confederates to hold for almost four hours. Finally, at 1 p.m., the Confederates, running low on ammunition, withdrew due to a daring assault by two Union regiments sprinting across the bridge combined with one of Burnside’s divisions threatening their flank from Snavely’s Ford. “Burnside’s Bridge” was now in Union hands, but it took Burnside another two hours to deploy enough forces and ammunition across the bridge before renewing the attack. The new assault began driving back Jones’ division, collapsing the Confederates toward Sharpsburg and presenting yet another opportunity to crack Lee’s lines if it could be exploited. However, A.P. Hill’s division’s arrival on the scene at 4 p.m. after a 17-mile forced march from Harpers Ferry shifted the momentum in the rebels’ favor. His flank attack disintegrated Burnside’s lines. By 5:30 p.m., the fighting ended, adding another 3,800 casualties to the total. Having had to respond to multiple crises throughout the day, Lee had depleted his left flank and abandoned Nicodemus Hill. Franklin sensed this and recommended attacking once more, but McClellan demurred. The battle was over.

In the end, Lee could not spring his trap. He badly overestimated his strength available for battle, as he had lost 27,000 of 65,000 soldiers (42 percent) to fighting and straggling since crossing the Potomac on Sept. 4. This forced him to exhaust his reserves to plug holes rather than mount a decisive flank attack. His army battered, Lee determined it was too risky to attempt a hasty withdrawal into Virginia while disorganized and in contact with the enemy, so he remained in Maryland another day. Meanwhile, McClellan, whose force had also been severely bloodied, wrongly believed Lee still outnumbered him. He chose not to press the fight further.

The Aftermath

The bloodiest day of the Civil War ravaged both sides. McClellan’s force of 87,000 suffered over 12,000 casualties while Lee’s 38,000 had over 10,000 casualties. Making matters worse, Lee lost several key leaders — killed or wounded — including 3 of 9 division commanders, 19 of 39 brigade commanders, and 86 of 173 regimental commanders. McClellan also lost key leaders, but not as many as his opponent: 2 of 6 corps commanders, 4 of 19 division commanders, and 6 of 49 brigade commanders.

With the defeat, Lee’s army had culminated, and despite his desire to continue the campaign after his withdrawal across the Potomac on the evening of Sept. 18, it was not to be. The largest army the Confederacy had put into field to date failed to achieve its decisive battle of annihilation. While Davis and Lee would surge forces once more during the following summer in the Gettysburg campaign, the U.S. Army would have an easier time reconstituting and growing after Antietam. The Union victory enabled Lincoln to issue the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. This made possible the enlistment of freedmen as U.S. Colored Troops, inflating the Union’s manpower base. By the war’s end, U.S. Colored Troops would make up approximately 10 percent of the force.

With the Confederate loss at Antietam, the fleeting opportunity of the high tide subsided.

After the battle, McClellan chose to encamp to reconstitute rather than pursue his defeated enemy. Despite Lincoln’s prodding, the cautious general would not move to cross the Potomac into Virginia until Oct. 26. Despite having to cover a longer distance, Lee outran McClellan, blocking his path to Richmond by Nov. 4. While tolerant of McClellan’s balkiness on military matters and near insubordination on political matters, this was the last straw for Lincoln. He fired McClellan on Nov. 5 — the day after the midterm elections.

Lincoln used the victory to issue his proclamation to free slaves in rebel territory, thus applying a moral frame to the war. The win also preempted foreign intervention on the side of the Confederacy, as the United Kingdom had contemplated recognizing and materially supporting the rebellion. However, the one-two punch of Antietam and Lincoln’s proclamation caused the British prime minister to back down. Thereafter, the Confederacy was alone.

In 1902, Ezra Carman, a colonel of the 13th New Jersey Infantry Regiment at Antietam, captured the enduring ripples of the battle:

Here was made history, here was rolled back the first Confederate invasion of the North; on this field was arrested the recognition of the Southern Confederacy and foreign intervention; on this field died human slavery.

Antietam Through the Years

As James Murfin wrote in 1965, “Antietam has been sadly neglected. It remains one of the most strategically impactful battles of the Civil War, yet its fields pass calmly through the years almost unnoticed.”

Indeed, Antietam had long been overshadowed by Gettysburg, where the United States achieved decisive victory, turning back the Confederates for good. Conversely, Union victory at Antietam had been accomplished through default, as Lee chose to leave the field of battle rather than fight on. Moreover, the victorious leader soon became tarnished: McClellan was relieved from command for failing to pursue Lee and went on to badly lose the 1864 presidential election to Lincoln.

Gettysburg overshadowed Antietam in other ways too. It lacked a prominent champion like Maj. Gen. Dan Sickles, who while in Congress sponsored legislation creating the Gettysburg National Miliary Park. Moreover, the famous Gettysburg Address, delivered by the president himself in the fall of 1863, spotlighted the pivotal battle and captured the public’s imagination. Finally, Gettysburg’s 51,000 casualties doubled the tally of Antietam, making it the bloodiest battle of the entire war.

It wasn’t until 1956 when Bruce Catton proclaimed Antietam as the Civil War’s turning point that it began receiving the attention it deserved. Later, civil rights activists highlighted the role of Antietam in the struggle for freedom and equality: Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. proclaimed the Emancipation Proclamation as one of the two most important documents in American history, underscoring the significance of the battle to the public.

Murfin’s masterful The Gleam of Bayonets, published in 1965, became the first comprehensive history of Antietam. Prominent Civil War historian Stephen Sears’ 1983 book Landscape Turned Red brought the battle to a broader audience. Joseph Harsh’s Taken at the Flood, published in 1999, provided fresh perspective on how Lee’s strategy influenced the Maryland campaign. Scott Hartwig’s recent two-volume offering, To Antietam Creek (2012) and I Dread the Thought of the Place (2023), have added to the literature a history rich with grainy detail.

In the immediate aftermath of the war and through even a century later in Sears’ work, the impact of Lee’s infamous “lost order” on the outcome of the battle has been overplayed. Some assert that McClellan was little more than lucky — absent the fortuitous discovery, he would have never bested Lee. Harsh strongly challenged this notion, while Hartwig proposes a more balanced assessment of McClellan’s generalship, which was instrumental in restoring Union morale after the Bull Run defeat and redeploying the army to engage Lee.

Another major revision in the historiography is the interpretation of Confederate strategy. Broadly, the criticism has been that the Confederacy, and especially Lee, lacked an appropriate strategic approach. Harsh’s book again provides a persuasive argument that the decisive battle of annihilation to undermine the North’s popular will was a sound strategy based on assumptions that were later validated: The South’s correlation of forces on the battlefield would only steadily decline as the war carried on.

In the last six decades, Antietam has stepped outside of Gettysburg’s towering shadow, and while militarily it was not a decisive battle, politically, it marked a distinct change in U.S. policy that shaped the ultimate victory to come three years later.

Why It Matters Today

Antietam offers several key lessons for practitioners and policymakers alike. First, at the strategic level, the battle illustrates what the strategist Colin Grey calls the “currency conversion” problem: converting tactical actions into strategic effect. Lincoln’s Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation transformed a modest battlefield victory into something far greater by helping to preempt British intervention in the war, ensuring the United States would only fight against ever-dwindling Confederate resources, while providing a new manpower pool to tap into.

On the other side, while Lee wasn’t necessarily seeking foreign intervention — he personally doubted that it would come — he sought a decisive victory prior to the midterm election. Instead, his loss deflated the surging momentum of his summer 1862 victories. Rather than seeing control of Congress potentially flip to the Peace Democrats, which could have forced Lincoln into negotiations or prevented his pursuit of emancipation, victory at Antietam stemmed the bleeding. Republicans retained a majority in Congress, albeit a narrower one. Tragically for the Confederacy, Lee’s Maryland Campaign undermined the political effect he had generated over the summer.

Second, regarding leadership, it is critical for decisionmakers to develop an ability to see both risk and reward. McClellan focused too much on risk, and in so doing, missed several opportunities to destroy Lee’s army and perhaps end the war. By contrast, Lee was nearly blind to risk, and his rosy assumptions about the timeline for the Harpers Ferry operations and McClellan’s expected sluggish pursuit of Lee’s army nearly led to a catastrophic defeat. By noon on Sept. 17, Lee’s only card to play was to hope for A.P. Hill’s arrival and for McClellan to blink. Both things occurred, and so his army lived to fight another day. For the modern leader, seeing both sides of the same coin — risk and reward — is vital to inform better decisions.

Lastly, it is simply not enough to identify lessons from past operations — one must implement them to learn from them. Lee failed here as well. His second invasion of the North would also end in defeat at Gettysburg for nearly the same reason as at Antietam: being caught off guard by a rapidly closing enemy while his own forces were dispersed. During the Pennsylvania campaign, Lee’s army was spread across a 60-mile arc and once again his cavalry had failed to properly raise the alarm. While this didn’t preordain defeat at Gettysburg, it lengthened the odds when he could ill afford it.

While the character of war has changed over the past 160 years due to new technology and evolving tactics, the takeaways of Antietam endure. As one Army War College student wrote after a 1911 Antietam staff ride: “We profit by the experience of others and learn [how the principles of war] were applied by the many able commanders who have led troops in the past.” Just as the U.S. Army studied the Battle of Antietam on the eve of World War I, so too should the nation and its military continue to study it a century later to identify and learn the lessons that were purchased at such a steep price in blood on the worst day of the American Civil War.

Mike “Shek” Shekleton is an Army strategist who currently serves as a research director at the U.S. Army War College’s Strategic Studies Institute. He has participated in nearly 40 American Civil War staff rides and recently started leading them. He has served in multiple assignments at the combatant command — and Headquarters, Department of the Army-levels, where he has developed strategy and campaign plans as well as examined strategic leadership.

Image: National Park Service