Join War on the Rocks and gain access to content trusted by policymakers, military leaders, and strategic thinkers worldwide.

“Why isn’t my J2 giving me the information I need? What do all these intelligence agencies do for me anyway?”

As U.S. military officers progress in rank, their relationship with intelligence evolves. Senior officers interact more with the intelligence community as the military assigns them to service component commands, joint task forces, and combatant commands. Further, technological advances and the increasing availability of data have made intelligence both more capable and complex. The operational-level commander has an intelligence officer — a J2, G2, N2, or A2 (we use J2 in this essay) — to help bridge the gap to the immense intelligence community, while also integrating its reporting with subordinate collectors. But it is inherently a commander’s responsibility to lead the management and integration of intelligence into operations: They should seek understanding, contribute to the collection effort, and tell their intelligence team what they need to succeed.

By doing so, senior military officers executing military campaigns can cultivate and lead a successful intelligence effort within their organizations. The best U.S. operational commanders from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have taken personal responsibility for their intelligence program: They have “owned” it. We base the observations offered here on interviews with military senior leaders, academic research, and our own lived experiences as intelligence officers.

Make It Your Own

The intelligence officer cannot bring the weight of the intelligence community to address the commander’s needs unless the leader shares their priorities and concerns. Gen. Joseph Dunford, the former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, emphasized that he needed to brief his intelligence team first on his priorities before they briefed him. Clear guidance enables the J2 to focus finite intelligence collection and analytical resources. To build this vital relationship, the J2 should be in the commander’s inner circle, traveling with him or her, attending daily close-out meetings, and striving to understand how the commander thinks. As the U.S. Central Command commander, Gen. Kenneth (Frank) McKenzie had an intelligence briefing every morning, then expected his J2 to give him regular updates throughout the day. While it is the J2’s responsibility to earn a spot in the inner circle, the commander first needs to afford them the opportunity to gain trust.

Senior leaders should also think of themselves as collectors. When a leader visits subordinate or adjacent units or conducts key leader engagements with a partner, they should share their impressions with the J2. An easy way to ensure this is to always bring the J2 — or a member of the intel team — on battlefield circulation, then compare notes immediately to ensure they both heard the same message. If an intelligence professional is not present for the engagement — especially with an allied or partner nation — a debriefing becomes essential. Several senior leaders we served under lamented the inaccuracy of information in national-level intelligence assessments. Gen. David Petraeus, while commanding in Iraq and Afghanistan, regularly challenged intelligence community assessments. When he became the CIA director, he ordered headquarters-based analysts to consult with intelligence specialists in theater to avoid this gap. Part of the challenge was that information from the commanders’ engagements remained in the senior leaders’ heads and never made its way into intelligence reporting. A disciplined strategic debriefing program can capture that information for broader consumption across the intelligence community, but the commander should first acknowledge their role as collectors. Disagreements between analysts will invariably still ensue, but at least they will be looking at the same reporting.

Regular commander-led deep dives with intelligence analysts is another effective technique for a leader to empower their intelligence teams. These direct exchanges build shared understanding and help refine the commanders’ intelligence needs. By removing the filter between the leader, who is interfacing with allies and senior officials, and the analyst, who is immersed in intelligence reporting, both sides will gain clarity. Gen. Scott Miller, when commanding in Afghanistan, regularly stopped by the sensitive comparted information facility late at night to speak directly with analysts — often unannounced. While every J2 would prefer the boss to let them know when they plan to visit, no J2 is going to complain about an engaged commander who values talking with their intelligence team. Simply asking good questions and providing clear guidance to the analyst is a critical step to becoming a good consumer. Refined, relevant, and specific questions will often emerge from these deep dive sessions and enable the J2 to shape collection requirements.

While the J2 will typically draft the priority intelligence requirements (PIR), they ultimately belong to the commander. Dunford told one of us that:

Often what we describe as intelligence “failures” could actually be characterized as leadership failures. Did the commander ask the right questions? Did the commander provide the right priorities for collection and focus? Did the commander properly supervise the prioritization and allocation of what will always be finite intelligence capabilities?

Miller gave guidance to his intel team through daily comments on his read-book, meetings with the J2, and frequent deep dives with analysts, and did not think that the priority intelligence requirements alone could “answer the many intricacies of the Afghan problem.” Miller wrote to one of us, “Writing the PIR was the easy part, but conditioning the force to look outside of the lines for when they felt the need to report was important.” Understanding those nuances only comes through regular interactions between leaders and intelligence professionals.

As leaders engage with their intelligence team, they should question analytical tradecraft and make analysts defend their assessments. Questions like, “Tell me about the sources you have supporting your assessment?”, “What is the quality of that reporting?”, and “Does anyone in the community disagree with you?” encourage analysts to think twice about their sourcing and talk to other intelligence agencies. Further, the commander’s perspective is unique, and they may come to a different, more accurate conclusion. The World War II practitioner and scholar Sherman Kent wrote about the consumer: “His remoteness from the fogging detail and drudgery of the surveillance or research may be the very thing which permits him to arrive at the more accurate synthesis of what the truth is than that afforded the producer.” Whether the leader’s instincts are correct or not, the conversation and accountability he or she demands by questioning the assessment is invaluable. Commanders should understand the assessment before they accept it.

Occasionally, individual raw, unanalyzed reports get widespread attention or are so revealing that it may be appropriate for the J2 to show a leader that report. However, including unanalyzed information in a read-book should be done with caution, as raw reporting — such as a signals intelligence intercept — lacks context and is ultimately just one piece of a larger puzzle. Yet, at times, having the commander review unanalyzed reporting can be useful, and some leaders demand this level of visibility. For example, we have witnessed instances when the CIA was planning to present critical human intelligence to the secretary of defense, and it was important that the subordinate task force J2 show the report to the forward-deployed commander and provide context. Similarly, when we asked Gen. Stanley McChrystal about how he makes his assessment, he revealed:

I found that simply asking a journalist or someone living in an area provided as accurate an overall assessment as all our collection. The secret is not to accept one over the other — it is to integrate them. In a simplistic example, I ask Alexa each morning about the weather — but I don’t decide what to wear until I’ve looked (and typically stepped) outside.

Related to raw reporting is the challenge of finding consensus among intelligence analysts and how to present opposing views. Even when looking at the same evidence, people will often reach different conclusions. The Supreme Court is a good example of this phenomenon. All nine justices are reading the same Constitution and its amendments, yet they rarely vote unanimously. Presidential Daily Briefers are required to inform their principals if there is a significant opposing view, and operational analysts should too — and commanders should ask.

In early 2020, when Lt. Gen. Bob Ashley was director of the Defense Intelligence Agency, there was a fierce debate between intelligence analysts across the “three-letter agencies” inside the Beltway and those in Afghanistan over how quickly the Islamic State in Afghanistan could attack the U.S. homeland after the U.S. military withdrew from the country. The Washington-based analysts believed it would take longer, while those in the country viewed the Islamic State as more capable and estimated the time to be less than half of the view from stateside. This assessment could influence how the United States would draw down its forces and the decision to withdraw at all. To try to find common ground, Ashley convened a classified video teleconference among the senior analysts involved in the debate who each presented their case with evidence. He concluded they were all reading the same reports, just interpreting them differently. The analysts never agreed, and ultimately, he decided on the assessment. Still, when he presented that decision to the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Ashley included a description of the opposing view along with the dissenting analysts’ justification.

It is the J2’s job to figure out how the commander prefers to receive information, but the best commanders are forthright with their preferences. Maj. Gen. Curtis Taylor, former commander at the National Training Center and 1st Armored Division commander, says analysts should be deep and thorough, but present information clearly and concisely: “Intel analysts often make the mistake of describing how they built a watch, when the boss just needs to know the time.” At the presidential level, George W. Bush preferred reading longer assessments and then engaging in conversation with the analysts. Barack Obama liked shorter summaries on an iPad followed by a briefing with his intelligence advisors. In his first term, Donald Trump favored less frequent sessions linked to relevant changes or major decisions and preferred visual aids (slides, posters, etc.) versus reading. Consumers can help their intelligence officers by sharing their preferences early on.

Finally, when analysts build a daily read-book, the leader owes them feedback. Thin, focused products — not fat, unfocused, and generally unread tomes — make everyone’s life better. Leaders should both ask questions and let analysts know when something piques their interest. In Afghanistan, Miller would type his comments in purple font on the daily update before sending it back to the staff, who would find answers to his questions and incorporate his input into the standing estimate. This guidance was incredibly valuable in focusing intelligence collection and analytical efforts. A word of caution, however: Be careful what you ask for. Asking questions based on curiosity versus relevance could pull finite analytical resources and collection platforms off more important tasks.

Speaking Truth to Power

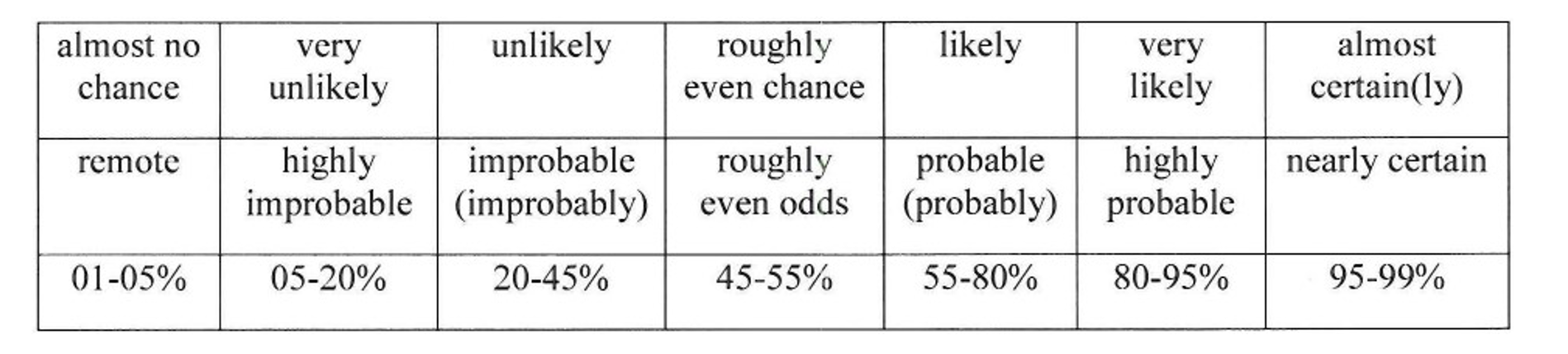

It is popular to claim that intelligence professionals should “speak truth to power” — expressing honest assessments to those in positions of authority. Yet we struggle with the word “truth” when referring to intelligence, and the scholar Mark Lowenthal calls this sentiment “both wrong and dangerous.” He argues that intelligence is not “truth” due to the complexity of human conflict, characterized by often unreliable sources and an adversary who is intentionally trying to obfuscate information. It is better for the intelligence officer to tell the consumer what they think, why, and to include a level of certainty. Gen. Colin Powell demanded that his analysts “Tell me what you know, then tell me what you don’t know, and only then can you tell me what you think.” The undersecretary of defense for intelligence and the director of national intelligence prescribe the use of certain qualifying words that correspond to percentages of certainty in assessments across the intelligence community. Despite this, commanders may dictate the words they understand best. Further, all the “likelys” and “probablys” bother some leaders, but it is important they know what they mean.

While “truth to power” may be inaccurate, the idea that the intelligence officer should at times disagree with the commander is critical, and while the J2 should be a part of the commander’s inner circle, there is danger in being too close. Groupthink and a desire to please the boss can cloud analytical judgement. In the words of Sherman Kent “If he sees his side the easy winner, the argument runs, he will tend to underrate the enemy; if the loser, to overrate the enemy.” This is particularly acute in a command climate where subordinates are intimidated by the leader. The 2022 Russian intelligence assessment that the Ukrainian military would roll over easily comes to mind: Who in President Vladimir Putin’s inner circle wants to tell him he’s wrong? The solution is to find the middle ground where the intelligence officer has enough information to focus collection and analysis without falling in love with the plan. Former Chairman of the United Kingdom Joint Intelligence Committee Sir Percy Cradock describes the intelligence officer-commander relationship this way: “The best arrangement is intelligence and policy in separate but adjoining rooms, with communicating doors and thin partition walls, as in cheap hotels.”

Of the dangers of being too close or too far, we believe the greater peril is the latter. The intelligence officer must know how their commander thinks but also recognize the risk of bias towards the “home team.” The J2 should step out or remain silent during operational planning, and the commander must respect that and be open to bad news that foils his vision. Our value proposition as intelligence professionals is that we are agnostic to the decision. Nevertheless, intelligence leaders must be prepared when the boss asks, “I got the assessment…what do you think?”

The Commander is the Best Intelligence Officer in the Unit

In 2013, after returning from an eight-month deployment to southern Afghanistan as a Brigade S2, then-Maj. Tom Spahr wrote that “Your commander is the best intel officer in the BCT [Brigade Combat Team]: Learn how he thinks, advise him on capabilities, and let his instincts be your guide. . . then present information to him in a way he understands.” This wasn’t a new idea then, and we still regularly hear senior military intelligence officers refer to the commander as the “best intelligence officer in the unit.” Yet at the operational level of war, we are more comfortable with the assertion “the commander is the most important intelligence officer in the unit.” This is not to degrade the commander’s intuition, but rather to acknowledge the complexity of operational intelligence and remind the J2 of their responsibility to be the expert. While the commander will make the final call on the assessment, as the volume of information grows exponentially, the J2 owes it to the leader to make sense of the torrent of data. Further, the J2 should be the expert on ever-evolving capabilities across the vast intelligence community. Nonetheless, the commander is the most important intelligence officer in any organization, because ultimately the only intelligence that matters is that which resides between the boss’s ears when making a decision.

Conclusion

Intelligence is a tough business, and even in the era of big data and artificial intelligence, failures will happen. Among military leaders, the adage that military missions come in two types — operational successes and intelligence failures — is alive and well. The commander is the most important intelligence officer in any organization, and they should own the vision of the enemy and the intelligence requirements. If the intelligence officer is not a comfortable fit in the commander’s inner circle or is not an expert at their trade, perhaps it is time to find a new one. But before firing the J2, the leader should ask themselves: “Am I telling them what I want? Am I a part of the collection team? Am I keeping my door open to the people and my mind open to the indicators?” If senior officers want intelligence to drive operations, they should own it.

Lt. Gen. (ret.) Robert P. Ashley, Jr. retired from the U.S. Army in November 2020 after over 36 years of active duty service as an intelligence officer. He served as the 21st director of the Defense Intelligence Agency (2017-2020); the Army deputy chief of staff, G-2 (Intelligence); the director of intelligence, U.S. Army Joint Special Operations Command; the director of intelligence, U.S. Central Command; the deputy chief of staff, Intelligence, International Security Assistance Force and director of intelligence, U.S. Forces, Afghanistan; and commanding general and commandant, U.S .Army Intelligence Center and School. He currently serves as a commissioner on the Afghanistan War Commission among other senior advisory positions.

Thomas W. Spahr, Ph.D., is the Francis DeSerio Chair of Theater and Strategic Intelligence at the U.S. Army War College. He served as a military intelligence officer for over 27 years before retiring from the Army in October 2024. Dr. Spahr served as the chair of the Department of Military Strategy, Planning and Operations, U.S. Army War College (2022-2024); chief of staff for the CJ2 (Intelligence), Operation Resolute Support, Afghanistan (2019-2020); and senior intelligence officer (G2), 4th Infantry Division and Fort Carson (2016-2018). He deployed as an intelligence officer to Afghanistan four times and Colombia twice and has taken part in several multinational training exercises in Eastern Europe. Dr. Spahr holds an M.S. and a Ph.D. in History from The Ohio State University and an M.S.S. from the U.S. Army War College.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

Image: U.S. Strategic Command