Join War on the Rocks and gain access to content trusted by policymakers, military leaders, and strategic thinkers worldwide.

The House and Senate appropriations committees each approved their own versions of the Fiscal Year 2026 Department of Defense Appropriations Act in July, which means that, as lawmakers return from August recess, it is appropriations debate time.

This year’s defense appropriations process has been unique on three levels. It is the first year that a reconciliation bill included defense funding, a windfall that brings final appropriations this year to over $1 trillion. FY2025 was also the first year that a defense budget was entirely funded through a continuing resolution (appropriations were left at FY2024 enacted levels). And, as legislators begin to prepare an appropriations package, it is the most disjointed and delayed defense budget process in history, as the Pentagon delivered topline justifications four months past the February deadline, with roughly $10 billion in accounting discrepancies. As such, Congress has crafted its budget largely in the dark.

Defense appropriations are increasingly hard to pass on time in a normal year. House defense bills need only pass a simple majority vote, while Senate lawmakers craft a bill that will attract 60 votes, creating different incentive structures — and consequently, bills — for each chamber. But the budgeting process this year has teed up appropriators for an unusual amount of debate, as a result of a delayed budgeting process that led to House and Senate appropriations bills with some of the largest topline differences in history.

As this year’s appropriations process offers real insight into many of the strategic and political debates that play out in Congress, Cogs of War is providing this summary of the House and Senate appropriations bills to understand why and where toplines differ.

How Significant Are This Year’s Differences?

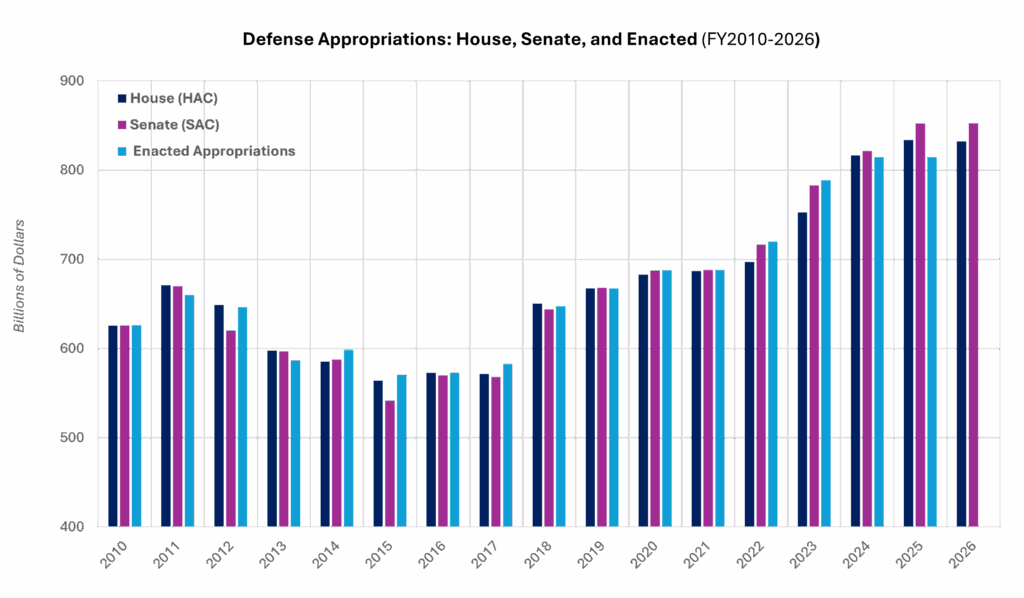

A quick history lesson. From FY2012 — the consequence of these cuts, sequestration, occurred in FY2013 — until FY2021, the Budget Control Act capped the amount of money appropriators were able to spend on defense and non-defense discretionary spending, leading to fairly similar toplines between the chambers. When the discretionary caps expired after FY2021, gaps in appropriations began to grow. Although the Fiscal Responsibility Act in FY2024 and FY2025 again imposed caps (with funding levels rolled over from FY2024 in last year’s continuing resolution), large spending gaps have persisted in years without statutory discretionary caps.

This year’s $21 billion funding difference between the chambers ($852.45 billion in total appropriations from the Senate, and $831.50 billion in total appropriations from the House, not including military construction or veterans affairs funding) for base defense appropriations is not the most significant funding difference between the House and Senate in history, nor atypical in that initial Senate appropriations are typically higher than the House.

But these continued gaps in appropriations point to a trend of differing strategic priorities between House and Senate lawmakers, even when chambers are controlled by the same party. This is partially attributable to the fact that a House bill can pass with a majority vote, often making it more partisan, while a Senate bill typically attracts a cloture-proof 60 votes, making it more bipartisan. But the uniqueness of this year’s process, and the large gaps in funding between the Republican-held House and Senate bills, indicate this year’s appropriations debate is more a product of congressional priorities than in the past.

A Supportive House and Assertive Senate

It can be more difficult to understand the appropriations philosophy of the House, as the House’s budget report that accompanies its budget is 100 pages shorter than the Senate’s and lacks a narrative element and clear justifications. But in reading the committee report and member press release summaries, it’s clear that while majority lawmakers in the House are critical of perceived waste and fraud in the Defense Department, they are generally more supportive of the Pentagon’s request. House appropriators are less willing to diverge from the Pentagon’s asks, with limited adjustments only for big-ticket items.

In its short report introduction, the House this year notes it was “hampered” by this year’s Pentagon legislative process but overall “appreciates the Administration’s shared dedication to eliminating waste and pursuing governmental efficiency within the Department of Defense and the Intelligence Community,” calling for further efficiencies.

Senate lawmakers, on the other hand, are happy to point out strategic and budgetary flaws in the Pentagon’s request. Senate appropriators are unwilling to simply accept the Pentagon’s requests without modification, and are frustrated by the Pentagon’s overreliance on reconciliation funding, which circumvents traditional appropriator oversight.

The Senate’s report is also highly critical of the Pentagon’s budgeting process, calling it “incomplete, inadequate, and inconsistent with long-standing practices and procedures”. It introduces additional oversight in areas like healthcare and limits general transfer authority by $2 billion. But in comparison to the House, it portrays the Defense Department as under-resourced, compared to the magnitude and diversity of the threats it faces, and is thus willing to diverge from (and criticize) the Pentagon’s budget request. It significantly marks up several House and Pentagon programs and priorities, while criticizing clumsy cuts done in the name of efficiency, such as those to the civilian workforce. And more critically, it argues this year’s $156.2 billion in reconciliation funding is not only appropriated inefficiently, but is a Band-Aid for the large investments the Pentagon needs to make in the next few years to counter proliferating threats.

The House’s public releases also advertise it as an innovator, a role typically held by the Senate. This year, the House heavily funds program innovation, research and development, and procurement programs, while overseeing deep cuts to day-to-day operations. Overall, the House’s investments portray it as a responsible institution willing to collaborate with the Department of Government Efficiency and the Defense Department to steward its budget, but also as an innovative institution willing to invest in cutting-edge priorities, with a look to the future fight.

The Senate adds considerable funding to the base Pentagon budget to bolster readiness, resilience, and personnel. It also symbolically funds several security partnerships the House cut. The Senate’s funding and willingness to cut general slush funds, call out program mismanagement, and strengthen the industrial base emphasize it as a corrector of Defense Department shortcomings and insufficient funding, and as the chamber concerned with maintaining equipment and relationships.

These differences suggest that the House and the Senate may have different interpretations of how and when to resource risk. Many of the research and procurement investments the House is proposing won’t be operational until the early 2030s. House appropriations are much more like the Pentagon’s, which suggests that both see the pacing threat peak as not coming for several years, if not a decade. On the other hand, the Senate is focused on investments in the broader industrial base and personnel now, implying a focus on near-future readiness.

Breaking Down the Budget

Between the announcement of the “Golden Dome” project and the Trump administration’s prioritization of the Pacific, there are plenty of shakeups that could be happening with service-level appropriations this year.

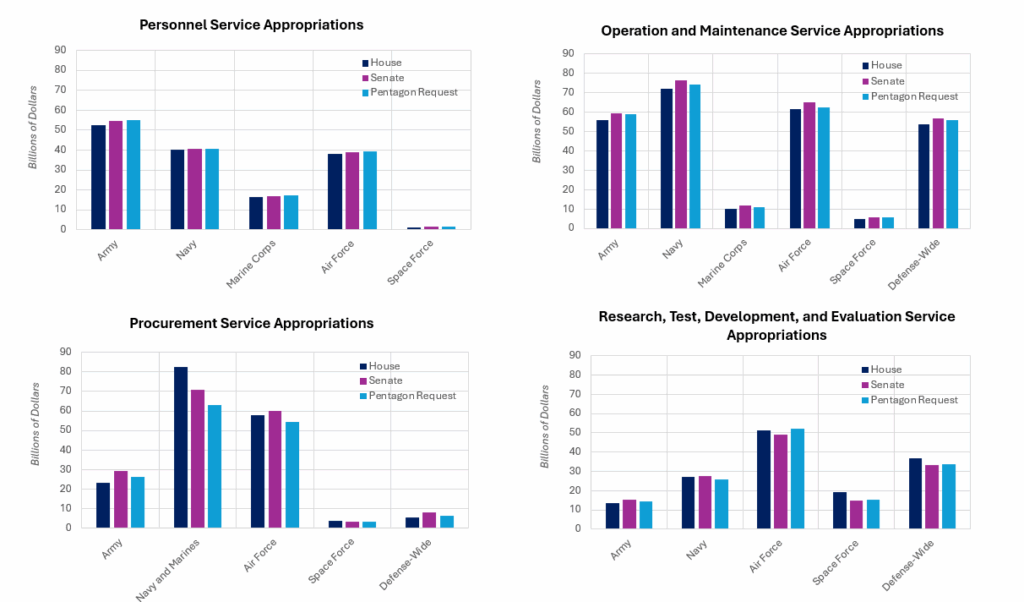

The House is willing to lean into the administration’s policy priorities, boosting Navy and Space Force procurement and innovation. The Senate, on the other hand, leans away from these policies, appearing skeptical of major research efforts from the Space and Air Force while providing strong support for the Army and general readiness.

The House, happy to throw its weight behind the president’s landmark initiatives, supports the Navy and Air Force’s procurement needs, and research and development in the Space Force and Air Force. The House’s hesitancy towards funding operation and maintenance, and willingness to cut legacy programs and additional support, indicates their chamber’s strategy is to invest in next-generation capabilities now — hypersonics, unmanned systems, nuclear modernization, and shipbuilding — while maintaining a smaller bureaucracy.

Alternatively, while the Senate was critical of the “disjointed” rollout of the Army Transformation Initiative, the Senate boosts Army appropriations across the board. This willingness to back the Army, despite the administration’s preparations for a Pacific contingency, is one of the most significant strategic breaks with the House and Pentagon.

And while the Senate is happy to invest in readiness (operation and maintenance, and transformations to the industrial base) across the board, the Senate is also clearly skeptical of the Air Force and Space Force’s ability to deliver on big-ticket, expensive procurement items and research. The Senate expresses concern about major cuts to legacy programs to fund unproven technology and research, despite this being a major feature of the Defense Department’s strategy.

The most intriguing differences occur in the four title accounts: military personnel, operation and maintenance, procurement, and research, development, test, and evaluation.

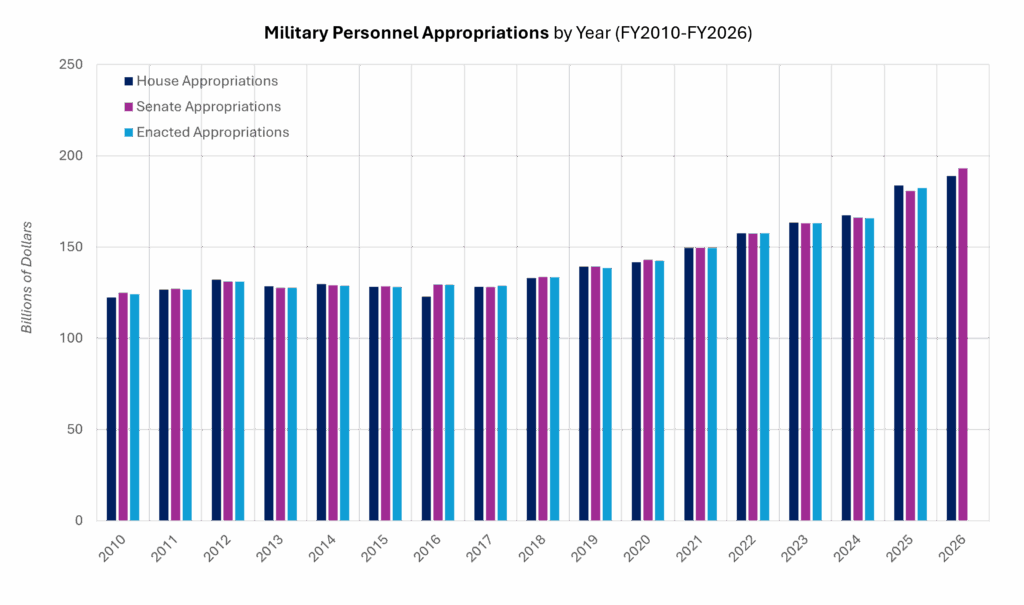

Military Personnel

Differences in (non-reserve) military personnel funding between the House, Senate, and Pentagon are relatively modest compared to the other title categories, as both chambers appropriated a 3.8 percent raise for all troops in FY2026. But even small gaps are notable, as evidenced by the relatively even spending on personnel across the services. Looking at data going back to 2010, this year’s gap between the House and Senate is the largest observed.

Without more precise House accounting, it is difficult to determine why this difference is so large, but it may come from the projected personnel end strength of each service and additions to it. The Senate recommends increases in personnel across the services commensurate with the Pentagon (accounting for 2.7 percent more soldiers, 3.7 percent more sailors, 0.4 percent more in the Air Force, and 6.1 percent more guardians, with no growth for marines).

Operation and Maintenance

Operation and maintenance appropriations are the source of not only the most significant difference in appropriations between the House and Senate in a title category since our dataset began, but also the largest appropriations to a title category ever. This could, in part, be due to low levels of operations funding during the FY2025 full-year continuing resolution — which continued FY2024 funding levels ($287 billion) — but can also be attributed to Congress’s history of using this spending bucket to pay for longer-term investments.

The House’s $283.4 billion appropriation cut significantly from the Defense Department’s request of $296 billion, while falling more than $17.8 billion below the Senate’s appropriation. The House significantly cut from the Pentagon’s operation and maintenance request across the board. In one of the most interesting plus-ups, the House overfunds the Pentagon’s acquisition workforce request by over 20 percent, while simultaneously cutting 45,000 civilian jobs.

The Senate, in contrast, adds billions in operations support, facilities sustainment and modernization across the services (although this money is cut for reserve organizations) to the House’s appropriations. Among several small programs at the Office of the Secretary of Defense that received significant plus-ups, $25 million was appropriated to reestablish the Office of Net Assessment.

Procurement

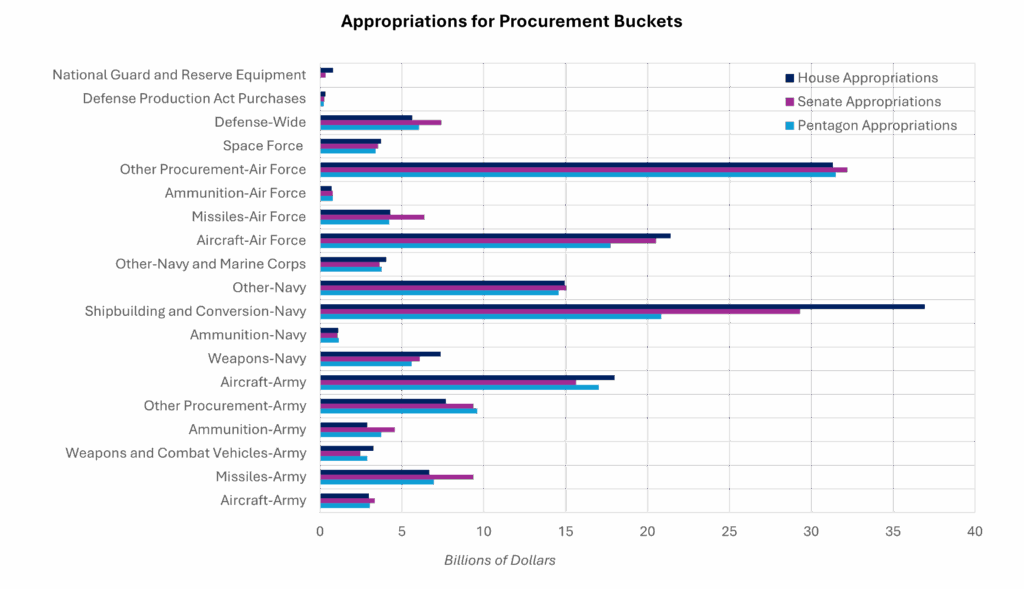

Although differences between the House and Senate procurement accounts are small (the House appropriates $174 billion and the Senate $171.3 billion), both chambers massively plus-up Pentagon procurement requests, which are extremely low at $153.1 billion. Appropriators were generally condemnatory of the Pentagon’s low request for over-relying on reconciliation funding and underfunding traditional procurement programs. Senate appropriators noted that, despite efforts to reform acquisition and budget processes, low procurement funding means the Defense Department will be “poorly served by such resource constraints.”

In the past decade, the Senate has typically driven procurement spending, while the House, hesitant to lock the government into long-term spending, has been more hesitant. But this year, that trend is reversed, with the House and Senate funding programs that again indicate differing strategic priorities.

The House, which significantly favors the Navy in this year’s procurement, adds more than $15 billion to the Pentagon’s shipbuilding request and boosts additional Navy weapons. It adds, across the board, to certain aircraft programs.

The Senate takes a more balanced approach. With the benefit of a few extra weeks of poor press about depleted U.S. munitions from the Russo-Ukrainian War and Israeli-Iranian War, it pours an extra $5.2 billion in missile procurement (characterizing existing procurement strategies as “unacceptable budgeting strategy”) and $2.1 billion for facilitating these plus-ups across the services. The Senate generally seemed more hesitant towards funding big-ticket items such as aircraft and ships than the House, but it is notably willing to add more than $5 billion to the Army’s account.

Specific programs drive procurement, and lawmakers in each chamber and officials at the Pentagon are at odds about the cancellation or reduction of several high-cost programs. Toplines diverge most in the numbers of F-35s lawmakers want to procure this year; the sunsetting of the A-10; the reduction of the E-7 Wedgetail program; the expensive F/A-XX program; the cancellation of the E-2D program; the continuation of the F-15EX program; procurement levels for the C-130 Hercules; the improved turbine engine program; the retirement of the U-2; the joint light tactical vehicle; and the landing ship medium.

The Defense Department is eager to adjust or sunset the U-2, F-15EX, A-10, and E-7 Wedgetail aircraft programs (programs which critics have argued are all some combination of slow to deliver, expensive, and of questionable operational relevance), likely to free up capital as it attempts to address modernization priorities. But both sides of Congress seem eager to keep these legacy programs, whether as insurance policies for the industrial base, interoperability, utility in specific operations, or political reasons.

Another interesting trend in procurement this year lies in the way the House and Senate buy weapons.

Senate and House expenditures on advance procurement have only grown further apart in recent years. The House has typically taken a guardrail approach to advance procurement, expressing concerns about the Defense Department overcommitting on multiyear contracts without congressional approval. Yet use of advance procurement by the Senate this year has grown as the chamber attempts to smooth inconsistent demand signals from the Pentagon. Last year, the Senate appropriated $13.7 billion, or roughly 7.8 percent of its procurement total, for advance procurement (although this was not followed through, due to the FY2025 continuing resolution). This year, advance procurement increased to $15.4 billion, roughly 9 percent of procurement, and was utilized for 19 programs, from the MQ-25 to the long-range stand-off weapon. The House only utilized advance procurement for the Columbia and Virginia class submarines. These differences square with the Senate’s portrayal this year as a maintainer of readiness, and the House as committed to more flexible, cutting-edge technologies.

Research, Development, Test, and Evaluation

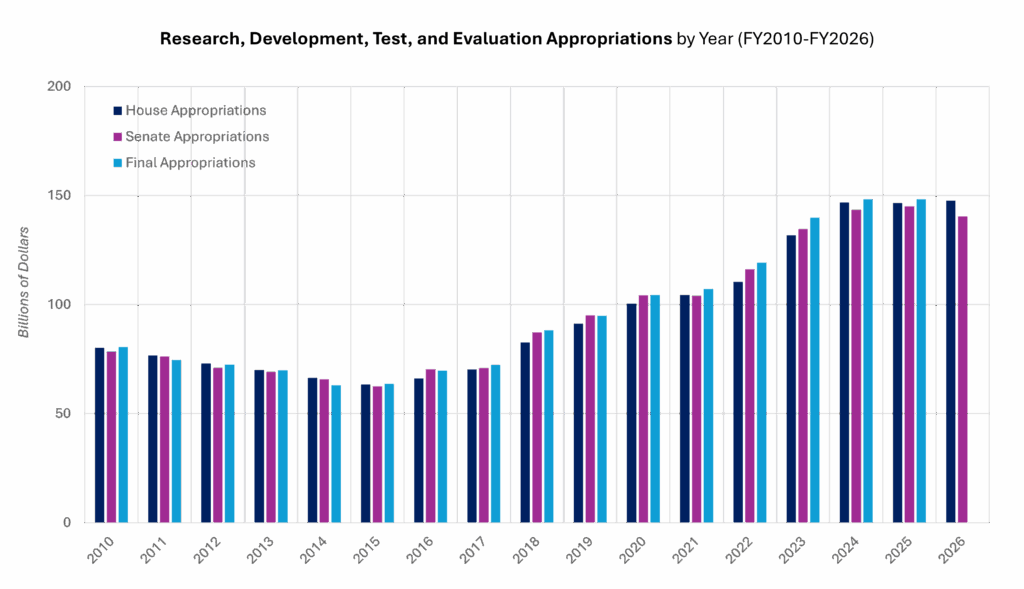

The House’s research, development, test, and evaluation appropriation is the largest proposed in history, emblematic of the House’s push for rapid innovation in the last several years. This year, the House appropriated $148 billion to the Senate’s $140.5 billion.

Although the House provides little detail on these investments, data from Next Frontier Intelligence and member press releases highlight investments in unmanned systems and missile, space, and hypersonics programs, with high appropriations for the Air Force and Space Force. The House adds an almost $8 billion request for defense-wide classified programs, which might be driven by continued modernizations to the nuclear triad.

The Senate again significantly adds appropriations to Army research, but slightly underfunds Air Force research in comparison to the House. Much of that difference comes from roughly $1.9 billion in cuts to the acquisition workforce, $1 billion in cuts from the classified programs, and almost $2 billion in cuts to zero out the survivable airborne operations center, while adding funds to the B-21, Sentinel, and F-47. While the Senate is happy to add money to the acquisitions workforce elsewhere, it is skeptical of some new, specialized programs to develop the Air Force acquisition workforce, which the House is happy to oblige.

This holds true in the Space Force too, where the Senate targets duplicative, immature next-generation communication and sensing programs for deep cuts. But the Senate generally moves this money into more mature programs and enabling infrastructure, indicating it is not unsupportive of the Space Force.

The Senate’s hesitation towards broad, unproven programs in the Space Force, which is responsible for the crux of Golden Dome implementation, is the most obvious example of a break in defense policy from the Pentagon.

While the House specifically highlighted its $13 billion for missile defense and space programs in its budget summary to help integrate Golden Dome, and appropriates more than $7 billion for Space Force classified programs, the Senate is less interested. The Senate cuts more than $4 billion from the Space Force’s research request and clearly states the Pentagon has not yet “provided the Committee with sufficiently detailed proposals to accurately assess a proposal commonly known as Golden Dome.” The Senate effectively declined to put down additional funding in FY2026 until it sees a program of record, directing the Secretary of the Air Force and Vice Chief of Space Operations to prepare a comprehensive briefing within 90 days.

Small-Line Strategic Differences

There are some interesting areas of strategic prioritization scattered throughout the line item allocations. These line items, at most a couple billion each, don’t have huge effects on the budget but have an outsized impact on the narratives each chamber weaves about its appropriations.

The House chose to highlight its rapid scaling and fielding initiatives, “continuing to prioritize innovation” by appropriating $1.3 billion total for the Defense Innovation Unit, Accelerate the Procurement and Fielding of Innovative Technologies (APFIT) program, and Office of Strategic Capital. The House also made some investments in experimental manufacturing base organizations, setting aside $131 million for a new Civil Reserve Manufacturing Network; significantly adding to the Pentagon’s request for the newly revitalized Defense Production Act (by adding $85 million, with $150 million of that reserved for biomanufacturing); and appropriating more than $1.3 billion to research on industrial preparedness. While relatively small, these investments in research, cutting-edge procurement, and new manufacturing models solidify their status as the ‘innovator’.

The Senate, on the other hand, generally chose to highlight initiatives to strengthen the industrial base and build in surge capacity while displaying hesitancy towards more innovative acquisition and procurement techniques. It condemns the Defense Department for seeking further innovation statutory reform as it is “already equipped with significant inherent authority to amend and improve their respective acquisitions and procurement processes.” The Defense Innovation Unit is the only innovation entity the Senate boosts (although they trim fielding dollars), and the Senate chastises the Office of Strategic Capital for a perceived lack of accounting transparency. Notably, the Senate cuts over a billion dollars in Pentagon requests for agile portfolio management across the Army, protecting and reasserting Congressional authority over the appropriations process despite calls by the Commission on Planning, Programming, Budgeting, and Execution (PPBE) Reform to allow for more flexible and responsive activity.

The Senate emphasizes bettering the manufacturing of advanced composites, rare earths and critical materials, printed circuit boards, and domestic motor supply as areas of need. They add over $2 billion to the Pentagon’s request to revitalize the munitions industrial base (noting “years of neglect”), while adding money specifically for the shipbuilding and space launch industrial bases. They add over $1.5 billion to the request for Naval engineering and manufacturing development (although they cut the Air Force’s by $300 million) and add small appropriations to programs that will all play a role in the future industrial base, such as rapid advanced deposition, additive process data, the domestic small unmanned aerial systems supply chain, and solid state additive manufacturing. It adds to several innovative manufacturing efforts and almost doubles existing funding for the ManTech program.

But the Senate is not uniformly supportive of broad slush funds, a trend that is apparent across the bill. It cuts appropriations to the Defense Production Act, seeming skeptical of it as a mechanism for executing improvements (the House, on the other hand, is supportive). It is also wary of broad, unjustified requests in biomanufacturing, and research for industrial resilience. Again, the Senate is wary of attempts by the Defense Department to grant it ultimate budgetary flexibility.

More major philosophical breaks are also apparent in the relatively small defense-wide sections of the Senate appropriations bills, where security cooperation partnerships lie (in contrast, these appropriations are scattered throughout the House titles).

The House, like the Pentagon, symbolically zeroes out several longstanding security partnerships — even though those cuts are unlikely to survive negotiations or will eventually be reversed through reconciliation — while the Senate signals a continued concern for these symbolic commitments. The Senate’s funding and report rhetoric indicate a willingness to protect these partnerships through appropriations fencing and appropriations through the normal budget cycle (rather than relying on assistance solely from reconciliation, which can be variable).

While admittedly neither chamber chose to break out the long-standing European Deterrence Initiative in funding this year, the House takes a limited approach to cooperative funding, appropriating, in addition to the Pentagon’s request, $500 million for the Taiwan Security Cooperation, $358 million for the Counter-ISIS Train and Equip Fund, $622 million for Israeli cooperative programs, and $1.15 billion for counter-drug programs.

The Senate, on the other hand, highlights $5.3 billion for security cooperation, including $1.5 billion for the new Indo-Pacific Security Initiative; an extra $800 million for the Ukraine Security Assistance Initiative; an extra $225 million for the Baltic Security Initiative; an extra $38 million for USEUCOM partnership efforts; continued funding for the Counter-ISIS Train and Equip Fund; and $500 million for Israel Cooperative Programs, among other partnerships. They also appropriate an extra $200 million for U.S. Africa Command and U.S. Southern Command each for operations, reupped the Taiwan Presidential Drawdown Authority, and appropriated $1.1 billion for counter-drug activities.

Again, while these appropriations are small in comparison to the entire budget (the Senate proposes a $4.6 billion budget for security cooperation programs), this section is an interesting reflection of the philosophical debate playing out across the chambers.

What’s Next in the Process?

Defense appropriations are likely to be wrapped up in an omnibus bill (as they have 14 of the last 16 years). A continuing resolution will likely maintain FY2024 appropriations levels until an omnibus passes late this year or in early 2026, if at all.

Although both chambers are controlled by Republicans, it will be hard for defense appropriators to come to consensus quickly for several reasons: the aforementioned policy and funding disparities between the chambers; the fact that they are beginning months late, having received the Pentagon’s full budget behind schedule; competing negotiation priorities between a likely continuing resolution, and the actual FY2026 bill; corrective funding issues, as this year’s continuing resolution has blocked new programs and funding; and the fact that defense is likely be caught in the middle of a broader political showdown about FY2026 funding that’s brewing on Capitol Hill.

As Senator Mitch McConnell has said this year, there is truly “no substitute for robust, full-year defense appropriations. This year’s appropriations process has also shown that for all attempts to encourage legislative reforms by the House and Armed Services Committees (take the SPEED and FoRGED Act), and Pentagon plus-ups intended to deliver timely innovation to servicemembers, appropriators still control the pace of reform and innovation. Under this dissonant approach to budgeting and strategy, it is the servicemember who loses the most.

Madeline Field is the assistant editor of Cogs of War, a vertical at War on the Rocks focused on defense technology and the defense industrial base.

Image: Midjourney