What is an Italian Carrier Strike Group Doing in the Indo-Pacific?

This week the Italian carrier strike group centered on the aircraft carrier ITS Cavour and the frigate ITS Alpino is pulling into Tokyo Bay. The carrier strike group is taking to Japan a 13-strong air wing of AV-8B Harrier II jets and cutting-edge F-35B aircraft fresh from some 180 flying hours and 110 missions at the Pitch Black exercise, including air-to-ground attack and suppression of enemy air defense actions. On its way to the archipelago, the group conducted also its first multi-large deck event in the region with the U.S. Navy’s Abraham Lincoln carrier strike group.

These are not the marks of a simple European diplomatic exercise in port calls and basic maneuvers away from familiar shores. The Italian navy is heading to Japan to present their professional credentials to their military counterparts as a way to underwrite the country’s ambition to develop a robust relationship. To that end, the navy’s training sailing ship ITS Amerigo Vespucci will join the Cavour, adding history and heritage to experience and cutting-edge technology. That is a naval statement with no equal in other European visits in recent times.

Such a remarkable engagement raises two rather fundamental questions. Why is an Italian aircraft carrier deployed to the Indo-Pacific in the first place? And, more importantly, why does it matter? The answers strike at the heart of a wider controversy. Experts have recently called for European actors to stay “out of Asia” as they strive to support Ukraine in its fight against Russia. Post-Cold War constraints from years of disinvestments in European naval capabilities make such calls a seemingly sensible choice. Others argue conversely that NATO, the European Union, and notably powers like the United Kingdom and France should continue to lead Europe’s engagement in the Indo-Pacific, especially from a maritime perspective.

In explaining Italy’s behavior, however, these assessments present three limitations. They first of all discount country-specific national interests beyond their relevance to the management of Sino-American tensions or, failing that, major conflict. Second, whilst Italy remains a G7 country and a major economic and political power, its role in the region is hardly ever fully considered, let alone understood. Third, European military engagement with the Indo-Pacific is articulated exclusively as a cost imposed on meager set of resources that bend the region’s military power balance out of shape.

This paper tackles these limitations to make a different case. Italy deployed the Cavour carrier strike group to the Indo-Pacific for three main reasons that, when understood in context, help in casting the wider European military engagement in the region in a different light. First, the Italian carrier strike group plays to the strengths of Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni’s foreign policy “new look,” signaling the strategic importance of expanding trade connections with actors across the Gulf and Indo-Pacific regions. Second, the deployment reinforces Italian efforts in wider strategic engagements with key partners — notably Japan — by showcasing Italy’s understanding of, and commitment to, the fragility of the global order at sea, the key pillar connecting Europe to East Asia. Finally, and unfolding from the previous point, the Cavour’s deployment is carefully designed to strengthen the development of an operational capability that has the potential to be central to one of Europe’s core power projection programs, the European Carrier Group Interoperability Initiative.

Italy’s “Enlarged Mediterranean” in a Contested Age

Before Meloni came to power in 2023, the Indo-Pacific stood beyond the commitments of a longstanding regionally focused naval and military posture. Today, however, her government’s “pivot” to the region is both a reflection of, and a driver for, the reconceptualization and expansion of Italy’s geopolitical concept of an “enlarged Mediterranean” that informs the country’s foreign and security policy.

In particular, this notion should not be understood purely as a widening of Italy’s geographic area of interest from the natural boundaries of the Mediterranean Sea to the shores of the Gulf and western Indian Ocean regions. Rather, it is the result of the Italian government’s understanding of the geo-economic opportunities unfolding from stronger interactions with Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. Indeed, within this enlarged Mediterranean vision, Italy is seeking to link maritime connectivity to economic development, and science and technology to the need to acquire advanced capabilities for a strategic edge capable of meeting the demands of unprecedented international competition and dangerous contestation.

For this reason, Meloni’s first actions focused on reinvigorating the country’s role as Europe’s economic bridge with Africa. Her strategy was articulated in her signature economic initiative, the “Mattei Plan for Africa.” This project, combined with the launch of the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor, created the ideal conditions for a structured approach to Italy’s influence in sustainable infrastructure and energy development initiatives across the three regions from the shores of the Mediterranean Sea to those of the Indian Ocean.

Against this background, it is worth recalling that efforts to reduce Europe’s energy dependency on Russia in the wake of the war in Ukraine, and the government’s decision to disengage from China’s Belt and Road Initiative — a choice consistent with Meloni’s earlier skepticism of the program — further contributed to a foreign policy outlook focusing on engagements to the country’s south and east. Of no less relevance, the longstanding challenge of migration across the Mediterranean itself had led Meloni to create an expectation during the electoral campaign that a conservative government in Italy would take firm action to tackle it.

Consistently, the Mattei Plan focused on Italy’s engagement with Africa, an area of the world in which the new conservative government sought to promote economic development as a way to help address, in part, the crucial issue of illegal migration. In June 2024, just a year after its official launch, the Mattei Plan received additional political validation through the support of the G7 Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment. This initiative was designed to support flagship projects to deliver “transformative economic corridors,” linking the Mattei Plan and the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor seamlessly.

By a similar token, Meloni’s visits to India and the United Arab Emirates in 2023 aimed at reinforcing this new strategic approach to foreign policy, with a clear emphasis on the future of the energy and security sectors. In particular, in India, Meloni announced that Italy would join Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Indo-Pacific Oceans Initiative, taking a leadership role on the science and technology pillar in a fashion consistent with her wider initiatives.

For the Meloni government, nonetheless, the promotion of new links in the Gulf and Indian Ocean stood next to an appreciation of the more fractured nature of world order. With war raging in Europe and maritime-centric crises growing from the Red Sea to the Taiwan Strait, the Italian government viewed links with actors within the Indo-Pacific as a distinct defense-industrial opportunity. It is in this context that Italy joined the Global Combat Air Programme collaboration with Japan and the United Kingdom. The idea to develop jointly a key capability in a major domain of future warfare espoused Italy’s desire to retain a military-technological edge.

Clear signs of Italy’s economic commitment to the program emerged in the aftermath of the announcement in December 2022. Recent Italian sources reported that the country’s bilateral trade with Japan had witnessed a 10 percent increase in 2023 compared to the previous year, reaching a total of some €15 billion. Stronger political links in terms of technological and scientific collaboration, together with the more favorable conditions created by the European trade framework between the European Union and Japan — enacted in 2019 — are likely to have contributed to this expansion of trade ties.

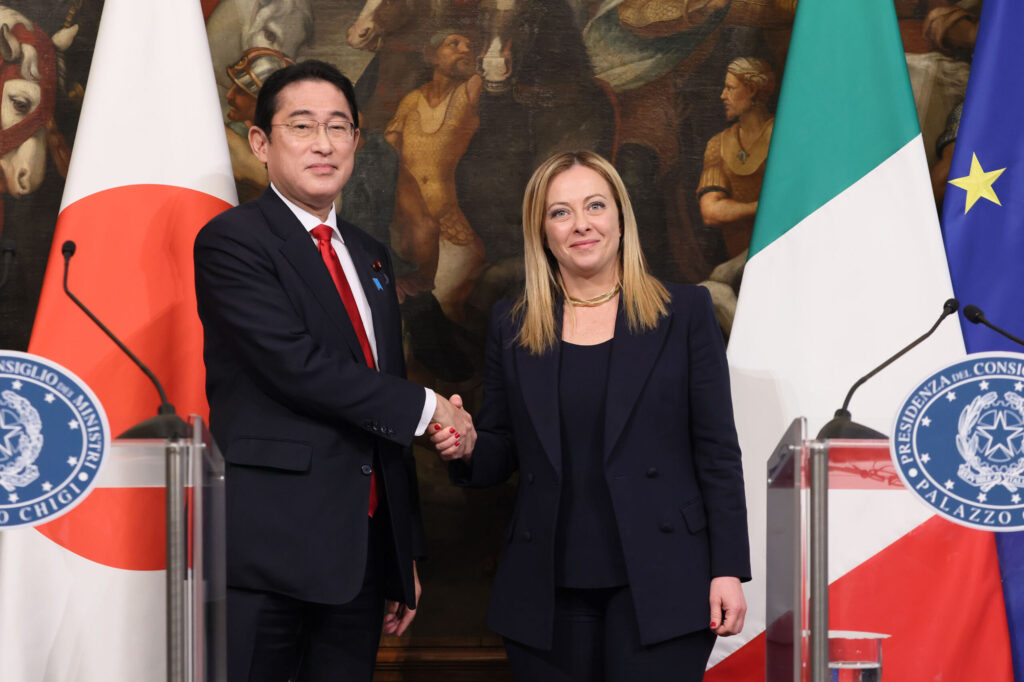

The strategic character of the relationship, which could draw on both countries’ participation in a reinvigorated G7 framework, was further restated during Meloni’s visit to Japan earlier this year. The two governments unveiled a series of new initiatives in the area of defense and security cooperation, including training, reciprocal visits, and activities within the framework of the G7 — the latter especially since Italy holds this year’s presidency. As plans for the Cavour carrier strike group visit to Japan firmed up, Italy used the deployment to militarily underwrite political actions, setting the stage for a security relationship aiming to settle on a qualitative character not too dissimilar to those enjoyed by the United Kingdom and France.

Maritime Statecraft the Italian Way

Against this renewed set of ambitious goals, the Italian navy stands as a key enabler to deploy the country’s capacity for statecraft beyond Mediterranean shores. Indeed, the Italian navy is a major tool for maritime statecraft, drawing in no small measure on a vibrant maritime commercial sector. Leading Italian commercial shipping company MSC is consistently at the top of the industry. Shipbuilder Fincantieri leads the field with a global footprint, with contracts from the United States to the Gulf and Southeast Asia, investments in ship repair facilities in Mexico, and plans to acquire shares of the TKMS group in Germany.

Maritime statecraft rests — as U.S. Secretary of the Navy Carlos del Toro has argued — on the strengths and synergic leveraging of commercial and military levers of power. In the Italian case, the navy’s professional capacity and operational confidence underwrite the country’s wider ability to achieve two crucial goals: to enhance national and partners’ capabilities, and to ensure maritime access to international sea lanes.

On the former, commercial and military synergies take the shape of Italian navy’s operational activities supporting wider capacity-building efforts through foreign sales. For example, last year, the deployment to the Indo-Pacific of the navy’s newest offshore patrol vessel, ITS Morosini, set the first step of this year’s carrier strike group campaign through an extensive operational schedule and multiple strategic port calls. Some of the planned activities, such as the ship’s five-day engagement in Indonesia, offered a clear opportunity to showcase the technological innovations of this warship to the Indonesian navy.

It is worth recalling that the warship featured a “light” configuration — one of three different options — that nonetheless leveraged technology to strengthen the link between the ship’s modularity and its operational flexibility, with some of the core innovative solutions including the futuristic naval cockpit and a digital battle damage assessment system.

In regard to access to sea lanes, the decisive Italian commitment to addressing disruptions to shipping in the Red Sea, both nationally and multilaterally, is a case in point. By January, Italian media reported that disruptions were costing the country €95 million per day. This is probably why Italy joined the U.S.-led joint statement condemning Houthi activities at the beginning of the year, and it was among the first countries to deploy anti-air defense capable assets to conduct close escorts to shipping well before the establishment of the E.U. operation ASPIDES (Figure 1). Indeed, by April 2024, Italy had a key leadership role in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden areas of operations. Cdre. Stefano Costantino had tactical command of ASPIDES, whilst Cdre. Francesco Saladino was in command of the EUNAVFOR Atalanta, and Capt. Roberto Messina led the Combined Task Force 153 responsible for Operation Prosperity Guardian.

Italian Warships deployed during this period: ITS De la Penne; ITS Fasan; ITS Martinengo; ITS Duilio.

Italian Shipping Companies: MSC, Ignazio Messina & C., Grimaldi Group, D’Amico Shipping, and SNAM.

Source: Italian Navy

Figure 1: The Italian Navy contribution to the Red Sea (Dec ’23 – May ’24)

Further, within ASPIDES, by the end of May, the Italian warships ITS Duilio and ITS Fasan had carried out 54 escort missions, the highest number of any contributing nation, with France — the second highest — conducting some 27 missions (Figure 1). Of no less relevance, Italian commercial vessels figured prominently in the escort activities with 91 ships sailing under close protection during the period from February to May 2024, compared to 23 French and 19 Greek vessels, suggesting a clear connection between the Italian shipping industry and the navy that is entrusted to ensure the safe conduct of its activities.

Such undertakings speak to two wider decade-long developments. First, thanks to policy support drawing upon the visibility the navy gained during its operational response to the migration crisis in the mid-2010s, Italy fields today one of the most balanced and modern fleets in Europe. Its surface fleet is the region’s second largest, together with the United Kingdom’s, and just behind France (Figure 2). Policy support for today’s fleet is in no small measure the result of Admi. Giuseppe De Giorgi’s declared ambitions to secure in 2014 a dedicated naval program. This was a vital step to guarantee a pipeline approach to shipbuilding worth €5.4 billion of investment over two decades.

Crucially, this program challenged assumptions about the country’s European-focused strategic outlook, inherent to the Law No. 244 approved just two years prior. In doing so, the navy’s argument anticipated an understanding of the need to engage in a wider area — beyond the Mediterranean into the Gulf and Indian Ocean region — that came to be espoused in the 2015 Defense White Paper.

* Data from 2023; ** Royal Fleet Auxiliary

Source: The International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance 2024 (London: Routledge, 2024), 54-157.

Figure 2: Pennant List of Main European Fleets

A decade on from its original approval, de Giorgi’s steely aspirations have become the enabling conditions to the present government’s ambitions. The seven ships of the Thaon de Revel class — the second and third of these having been crucial to the Indo-Pacific engagements over the past two years — represent, together with the LHD Trieste, the physical manifestation of a wider operational reach and illustrate the point about the impact of maritime statecraft.

The second long-term development concerns the Italian navy’s choice a decade ago to renew its commitment to national security by investing into a more active role in environmental management and governance. This, in turn, enabled its leadership to make a case to retain a primary function in marine protection, including a dedicated patrol force of six vessels, and to lead through undersea research and marine science in the emerging space of seabed and critical infrastructure security.

By the end of 2023, Italy could count on a normative framework, the “Sea Plan” (Piano del Mare), that encapsulated all aspects of governance responsibilities for different departments of government, civil society, and the private sector to ensure a sustainable, safe, and secure use of the sea. Within this context, the navy led an effort to organize a “national undersea community” (Polo Nazionale Subacqueo) including public, scientific, and private actors to ensure adequate understanding of, and action over, the protection of critical undersea and seabed infrastructure. This plan was also closely aligned with the previous government’s strategy for the defense and security of the Mediterranean region adopted in 2022.

With expectations of the seabed continuing to grow as a crucial area of future economic development and conflict, the Italian navy’s investments in this area, not least through an undersea information monitoring center at its fleet headquarters, has renewed its efforts in placing naval activities within a wider understanding of the modern roles of maritime forces in statecraft — as the navy’s recent commitment within NATO on this subject would attest.

An Operational Deployment for an Operational Capability

Still, the quality of maritime statecraft relies on naval proficiency. From an operational perspective, the Cavour’s deployment is a reminder of the fundamental notion that geography is an opportunity, not a cost. For an organization of the structure and experience of the Italian navy, the counterintuitive notion that the ocean is one single large playground means that the boundaries for the conduct of peacetime operations are dictated predominantly by the capacity for logistical support and the scope of a political mandate, not by geography.

Indeed, the navy’s concept of operations is based on the principle of expeditionary sea-based activities. Within this construct, the carrier strike group generates sustainable air sorties in national and coalition operations to project national power and status away from Italian shores through command headquarter functions, maritime situational awareness, and joint intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance capabilities. Equally significant, the Cavour is equipped with hospital facilities up to NATO Role 2 enhanced level to support humanitarian and disaster relief missions, as it did in operation “White Crane” in the aftermath of the earthquake in Haiti in 2010.

MA: Mare Aperto; DYMR: Dynamic Mariner; POL: POLARIS

Source: Italian Navy

Figure 3: Mare Aperto exercise series, 2023-2024

With the introduction of fifth-generation aircraft capability with the F-35B, the Italian navy has upgraded its carrier strike component and this year’s deployment thus became a unique opportunity to work toward an Initial Operating Capability status that would meet national and international commitments. Starting in May, the Cavour took active part in the largest naval exercise in the Mediterranean Sea since the end of the Cold War — witnessing the convergence of the Italian Mare Aperto exercise with the French POLARIS exercise, involving some 50 naval assets and 10,000 personnel (Figure 3). The Cavour operated both as at-sea direction of exercise and as the main strike group platform together with the French Charles de Gaulle carrier group. The four-week-long activities tested the Cavour’s carrier air wing, command, and expeditionary functions, especially as it faced the experienced French carrier group.

Notably, the deployment to the Indo-Pacific took stock of prior Mare Aperto exercises, including the October 2023 edition that was conducted together with the NATO exercise Dynamic Mariner — a major test in interoperability bringing together 14 allied nations and 6,000 personnel (Figure 3). Equally important had been the Neptune Strike exercise in 2022, which added the important element of transfer of command authority to STRIKEFORNATO. On its way to the Indo-Pacific, the carrier strike group reaped the fruits of prior activities and put them to test against ongoing operations, supporting the Noble Shield, ASPIDES, and Atalanta operations and enjoying phases of interoperability and interchangeability with Spanish and French escorts.

Against this background, interactions with Australia and Japan added two significant aspects to the carrier strike group’s operational journey. First, they are facilitating a more granular understanding of the region’s environment and second, they are directly contributing to achieve the Initial Operating Capability status that will be essential in a continuous development of the European Carrier Group Interoperability Initiative. For the navy, Pitch Black represented one such critical step, and the Cavour brought to Australia for the first time ever a sea-based combat aircraft component to the exercise. In Japan, interactions with the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force will represent the culminating point of a deeply operationally focused engagement with Asia that pays dividends directly to a crucial capability in Europe.

Conclusions: Italy as a Major European Actor Working with Asia

The Cavour carrier strike group’s arrival in Tokyo should not be seen as yet another European “showing the flag” journey in distant waters. It comes hot on the heels of a substantive training and engagement schedule in which engagement with Asian partners advances Italy’s pursuit of a fifth-generation carrier strike capability and signals the country’s concerns over the fragility of the international maritime order. It is a flag-bearer for an economic connectivity strategy and a security strategy for the Mediterranean in which the geographical boundaries of this theatre extend eastwards beyond the western Indian Ocean. These are important political steps indicating a commitment to maintaining a technological edge in defense and to working with others to do so — regardless of geographical boundaries, because their uses apply across different interlinked theatres.

This is why Italy’s activism east of Suez should matter to allies and partners from Washington to London, from Canberra to Tokyo. Meloni’s Italy shares with each of them a worldview that places prosperity and governance at the heart of the country’s foreign policy seeking to link Europe, Africa, and Asia. Since 2022, Italy espoused also a national strategic concept that is aligned with the principles of the various free and open Indo-Pacific initiatives and brings strong equities in Africa, the Gulf, and the Indian Ocean with crucial maritime statecraft initiatives, notably around the future of seabed governance and security. This concept places international cooperation, notably through the Global Combat Air Programme — but potentially also through the F-35B — at the center of industrial collaborations, foreign sales opportunities, and operational advantage. As evidence of security links among Russia, China, North Korea, and Iran increase, Italy’s increased understanding of, and familiarity with, the Indo-Pacific and its key actors through this wider canvass of initiatives stands as a force multiplier in the ability to meet challenges from authoritarian regimes.

Italy’s case, therefore, strongly suggests that Europe should not stay out of Asia. Rather, it should strive to anchor national interests to ways to work with Asia to ensure that the two regions remain stable. Looking ahead, though, Italy’s main challenge is one of long-term sustainability of numerous military commitments. The Cavour’s deployment is showing a modern, proficiently run, and technologically advanced fleet that is part of a wider European construct. This year’s in-depth interactions with Australia and Japan, and the confirmed U.K. carrier strike group deployment next year, offer circumstances for ways to extend Italy’s Indo-Pacific endeavors in the near term.

Beyond that, much will depend on other factors, not least developments within NATO in relation to the war in Ukraine. What is certain is that the strategic and economic factors that have propelled recent initiatives — not least the carrier strike group deployment — are unlikely to vanish anytime soon, and these serve as the main guarantee for Italy’s enlarged Mediterranean horizon to remain as such and for its allies and partners to make the most of it.

Alessio Patalano is professor of war and strategy in East Asia and codirector of the Centre for Grand Strategy at the Department of War Studies at King’s College London. In May 2024, he participated in the Mare Aperto/POLARIS exercise on the aircraft carrier Cavour.

Image: Government of Japan via Wikimedia Commons