Every Arsenal Needs Its Fans: The Missing Piece in the National Defense Industrial Strategy Is Voters

In 2022, Arsenal Football Club witnessed something it had not seen in years: rambunctious fans riling up the stadium for the entire game. Anchored by fan groups such as RedAction and the Ashburton Army, games at Emirates Stadium transformed from staid events, where the atmosphere was compared to that of a library, to wild, raucous contests where fans never stopped rallying the club. This transformation benefited from strong performances on the field, but the switch flipped when the club cultivated and supported its hardcore fans, those who wanted to make the games as fun as possible but lacked resourcing and access. Arsenal, it turns out, needed to activate its fans to truly take off.

Such is the case with America’s arsenal as well. That the arsenal for democracy needs a dramatic transformation is clear. Policy experts, military officials, and political leaders from both sides of the aisle have all called for urgent reforms to the nation’s defense-industrial base. And there has been progress — the Department of Defense recently released its first ever National Defense Industrial Strategy, for example. But among the many challenges this strategy faces, one weakness stands out: the absence of any deep public support for reinvigorating the arsenal.

This reflects both short- and long-term developments. More recently, domestic considerations have dominated electoral politics, reducing the incentive for political actors to prioritize defense spending as a campaign or governing issue. The longer-term drivers include the consolidation of the defense industry and the professionalization of the national security sector, trends that have (inadvertently) rendered defense policy debates less accessible for the citizenry at large.

Specifically, there is little political infrastructure to organize and mobilize voters across the political spectrum to support the “generational change” called for in the National Defense Industrial Strategy. Political infrastructure in this context refers to organizations and associations that connect Americans for collective political action. The defense sector’s political infrastructure is thin and highly professional, concentrated narrowly among defense insiders, with few organizations that interface with Americans outside the sector at any kind of scale. This makes for an effective lobby able to skillfully advocate on Capitol Hill, but not a movement able to activate legions of committed supporters.

The private sector should step in and create political infrastructure that can drive dramatic improvements to the defense-industrial base. This will involve thickening existing infrastructure, creating new civic and political organizations, and channeling the public towards sustained engagement in budget and policy debates. The public sector lacks the capabilities for this kind of cross-partisan public engagement, but American business, philanthropy, trade associations, think tanks, and existing civil society groups can lead the way and activate die-hard fans for America’s arsenal.

The Thinning Out of Defense Political Infrastructure

In his March 1983 address to the nation on defense, President Ronald Regan described his defense plans, and specifically the Strategic Defense Initiative, by saying: “My fellow Americans, tonight we’re launching an effort which holds the promise of changing the course of human history.” The same ambition is needed today for a once-in-a-generation initiative to transform the defense-industrial base. This will involve increasing the budget by 50 percent or more and require prioritizing America’s arsenal over compelling policy alternatives. Yet absent from most analyses of the situation and from the broader policy discussion is any real plan for generating the public support necessary to drive this kind of a commitment.

This is a major challenge. While 77 percent of American adults said they support increased government spending on the military, national security is ranked as a top concern by few Americans. Only 1 percent of Americans had national security as the top concern in the latest Gallup data and only 40 percent of Americanstold the Pew Research Center that strengthening the military should be a top priority compared with 73 percent who said strengthening the economy should be the top issue. This data suggests that while Americans might support increased defense spending in the abstract, there is no mass constituency demanding major reforms, especially when presented with competing demands.

Indeed, Americans are just as likely to support cuts to the defense budget as they are increases. Americans are also more likely to prioritize a range of other policy issues, such as immigration, the economy, and the budget deficit. While recent polling suggests Americans might be paying more attention to foreign affairs, there is no evidence to suggest voters will support a massive effort to invigorate the arsenal. If anything, worsening fiscal constraints — this year debt payments are set to exceed outlays for defense — could make Americans even less inclined to increase the defense budget.

It would be easy to attribute the public opinion challenge to more recent developments. Frustrations with “endless wars” caused many Americans to turn more inward. A hyper-polarized politics may have distracted from substantive issues such as defense. Then the worst inflation in 40 years held voters’ attention even as the national security environment worsened dramatically.

But there are also longer-term societal shifts that have changed the defense sector’s political infrastructure and, as a consequence, made the defense-industrial base a priority issue for fewer Americans. The first of these trends is the reduction in the number of people, places, and businesses directly impacted by the military and defense industry.

In 1985, for example, at the height of America’s last peacetime transformation of its arsenal, approximately 3.1 million Americans worked in defense-related industry. As the National Defense Industrial Strategy notes, there are now 1.9 million fewer people working in the industry, even though the total population has increased by almost 100 million. Similarly, over the same time period, the active-duty force has dropped from over 2 million to approximately 1.3 million.

This decline tracks the reduction of physical settings or places directly connected to the defense budget. Over the past half-century, more than 100 major installations closed as part of the Base Realignment and Closure Commission process. As a result, whole sections of the country lost geographic connection to the defense sector.

Finally, the presence of businesses that serve the defense sector has shrunk over time. This reflects both consolidation and geographic concentration. While there are benefits to creating defense-industrial clusters or hubs, the net effect of these changes has been to dramatically reduce the proportion of voters who regularly take part in or directly experience defense spending conversations and decisions.

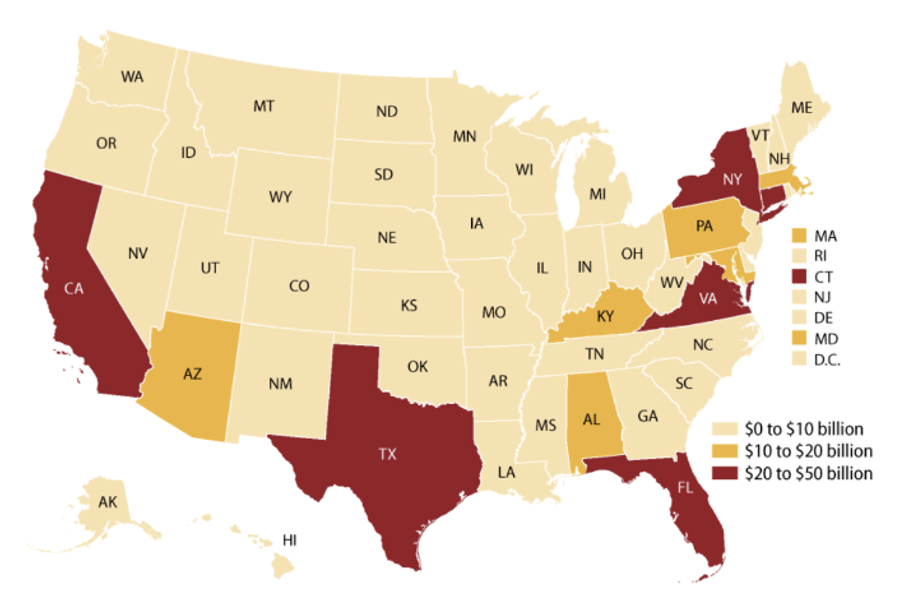

Imagine looking at a map of the country that had a small light showing every household where America’s arsenal was a kitchen table issue. Going from 1985 to the present would show a steady march towards darkness. There would be a brief explosion of light during the height of the war on terror, but relatively quickly the lights would start disappearing again. By the time you got to the present, there would be bright spots around places like Washington D.C., Huntsville, San Diego, Norfolk, and Dallas, among others, but most of the country would be dark.

Figure 1. Department of Defense Contract Spending by State, FY2022. Source: Congressional Research Service, “The U.S. Defense Industrial Base: Background and Issues for Congress”.

As challenging as such a map is for public engagement, it’s not the only obstacle. Just as defense conversations have grown more remote for most Americans, they have also become much less accessible. Driven in part by technological innovation, but even more so by the overall professionalization of the national security sector, defense policy debates now feature much greater technical sophistication than in earlier periods. This shift has yielded many advantages, but it has also led to political infrastructure focused on winning narrow (if important) policy disputes among professionals versus mobilizing the mass public.

The story of how a highly specialized national security profession came to dominate defense conversations does not have a defined starting point, but it would be reasonable to trace it to the development of atomic weapons in the 1940s. As Morris Janowitz articulated in 1960 with The Professional Soldier, atomic weapons were a catalyst for both technological and organizational revolutions in warfare, with specialists and managers assuming positions of greater importance. By 1960, this was already evident among defense contractors. Whereas the arsenal that won World War II was built primarily by Americans with little to no prior military training or expertise, the arsenal that won the Cold War was built by Americans whose experience was almost exclusively with the defense establishment.

The story extends far beyond the defense–industrial base, however. National security studies as an academic discipline took off in the aftermath of World War II. The National Security Act of 1947 codified into a law a more defined and civilianized defense establishment. In the same time period, universities opened new, security-focused graduate programs and journals. In 1948, RAND became an independent organization and helped usher this new field into being. Over the ensuing decades, the national security profession has continued to grow. As exemplified by this media platform, there is now a global ecosystem of professionals able to discuss, debate, develop, invest in, and otherwise take action on highly specialized national security ideas, strategies, and technologies.

The professionalization of the defense sector reflects a broader pattern in American civil society. A recent study of organizations that provide civic opportunity found that over the past half-century, civil society has become dominated by issue-specific and professional organizations, which frequently offer less opportunities for Americans who lack subject-matter expertise to build civic skills. While further study is needed, such findings support the idea that the defense sector has grown increasingly professional and insular.

The benefits of this development are enormous. Deep reservoirs of specialized knowledge and experience enabled America’s Offset Strategy so pivotal to ending the Cold War. Professionalization helped reduce barriers to participating in national security and enabled the field to harness the talents and contributions of a much wider array of scholars, entrepreneurs, scientists, servicemembers, and civil servants. Finally, it fortified American civil-military relations through all the tumult of the past several decades.

Yet the professionalization of the defense sector has also come with costs, many of which have grown more acute in the post-Cold War era. Over the past several decades, liberals and conservatives have grown more polarized in their views and Congress has become more divided in how it acts on legislation. This same time period has also seen a decline in Americans’ trust in a variety of institutions and in how honest or ethical they perceive various professions to be. This landscape increases the risks any major national policy effort faces, as it is now easier to frame an issue as partisan or as a project of elites.

The defense sector is highly vulnerable to such risks. Much of the defense conversation now plays out in academic journals and other outlets with paywalls or via think tank activities that require familiarity with a highly technical vocabulary prone to jargon. Lobbying and advocacy related to the defense budget is primarily the terrain of a narrow set of industry and political organizations staffed by experts. And unless someone serves in the military or takes specialized courses in college or graduate school, there are few opportunities in American life to gain the familiarity with the defense space necessary to effectively influence policy debates.

This setup leads to a paradoxical situation, where the defense sector’s political infrastructure can successfully lobby and advance meaningful reform, but it cannot drive transformational change. This was evident with the FY2024 appropriations as well as with President Joe Biden’s FY2025 budget. One of the highlights from the appropriations was an $800 million increase to the budget for the Defense Innovation Unit. This is an important improvement to America’s arsenal that had the support of well-positioned expert advocates — in this case the Silicon Valley Defense Group, among others — but the overall budget was only $27 billion greater than FY2023 funding, far from a revolutionary shift. The FY2025 budget proposal, operating under caps imposed by the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023, actually reflects negative real growth over the past two years when factoring in inflation.

Achieving the defense-industrial domination called for in the National Defense Industrial Strategy will require new political infrastructure that engages the mass American public. Forging such networks is an urgent challenge — and opportunity — that the private sector should take up.

How The Private Sector Can Generate Fans for America’s Arsenal

A successful, privately led effort to mobilize support for reviving the defense-industrial base should have three layers. First, thickening existing political infrastructure. Second, creating new political infrastructure that connects with Americans who lack a direct relationship with the defense sector. Finally, forging an intentional political strategy, with clear goals, plans, and compelling narratives.

If we think back to the map showing where Americans regularly engage with the defense sector, thickening political infrastructure is about making bright spots brighter. The goal is to ensure that as many people as possible who have a direct connection to the arsenal are also connected to organizations that can move them towards political action. For example, Department of Defense Manufacturing Innovation Institutes have over 2,000 member organizations and in just one year they had over 80,000 Americans interact with them. Are all these organizations and individuals connected to a membership or advocacy organization focused on defense policy? Could a campaign in support of America’s arsenal easily reach all these people? What about parents of students involved in programs funded through the Department of Defense’s STEM Strategic Plan? Or the more than 360 organizations participating in the Microelectronics Commons initiative? Thickening political infrastructure is about making sure the answer to all these questions is yes.

Creating new infrastructure is about turning dark spots on our map bright. This work will look differently across populations and will include both online and offline efforts. Examples of new political infrastructure could be defense industry clubs at graduate business, computer science, or engineering schools or new skilled trades programs that introduce people to defense contractors. But new infrastructure can also have a lighter touch. It could be discussion groups within religious communities that bring in speakers from the defense sector or volunteers committed to sharing news and information about the defense-industrial base on community social media pages. The entry points will be varied. The key is to reach beyond defense insiders, which requires meeting people where they are and offering programming and experiences that speak to their immediate needs, interests, and identities. Over time, this new infrastructure builds skills and relationships critical for individuals to feel part of the defense movement.

The final piece is an intentional political strategy that mobilizes the infrastructure to influence policy and electoral outcomes. The key elements for this piece are policy goals (the “what”), advocacy and electoral plans (the “where” and “how” of influence), and bold narratives (the “why”) that cut through today’s fractured information landscape.

The narrative piece is critical. America’s arsenal needs stories that go beyond the text of policy and tell us who we are, why this matters, and what it will feel like when we succeed. Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative provides an example of how the private sector can create such narratives. First, over the course of the 1970s and early 1980s, businesses, most notably technology firms in the recently named Silicon Valley, forged new political infrastructure tied to America’s arsenal and created an optimistic narrative about technology’s potential for improving human society. Then in 1982, as part of a broader initiative on national security, the Heritage Foundation published “High Frontier: A New National Strategy.” This report tapped into the existing political infrastructure to offer a new story about America’s defense-industrial base.

The “High Frontier” story had three key narrative elements. First, it offered a new framework — “assured survival” — to replace “mutual assured destruction.” Second, it positioned potential space systems as fundamentally defensive in nature. Finally, it established a historical context, branding the flight of the Space Shuttle Columbia “a new era of human activity on the High Frontier of space.” Reagan picked up on all three of these elements in his 1983 address to the nation.

A comparable effort is needed today to discern, craft, and elevate compelling narratives for the defense sector. Rather than attempt to generate such narratives ex ante, a better approach is to surface ideas through conversations with regular Americans from outside the defense space. Finding calls to action that are neither hyper-partisan nor blandly consensus-oriented will not be easy, but the best source for inspiration is the American people themselves.

All of these actions, from making existing political infrastructure denser and standing up new organizations to moving the whole network towards a coherent political strategy, are ones the private sector can lead. The defense ecosystem, including partners in philanthropy, think tanks, and civil society, should provide the leadership, resources, and support necessary to turn this sketch into reality and light up the map.

Conclusion

America’s arsenal needs fans. It needs the equivalents to Arsenal’s RedAction, voters willing to do the hard work of reaching out to people, organizing meetings, and talking with defense insiders and, more frequently, defense outsiders, about America’s arsenal. It needs supporters who can comfortably speak with their neighbors about why the arsenal matters and how transforming it will make a positive impact for the nation, their community, their families, and them as individuals.

Activating such fans requires political infrastructure, the spaces and organizations where people connect, build relationships and skills, and mobilize for advocacy and electoral purposes. And as with sports, mobilizing fans requires an intentional strategy that harnesses the infrastructure for coordinated action. Arsenal Football Club had to make a strategic commitment to working with and empowering its most ardent fans in order to unleash their full potential.

The defense industry and its civil society partners should make a similar commitment today. Right now, America’s defense sector has the best players and the finest coaches in the league. But the greatest championship teams, those that don’t just win but dominate the competition, need more. They need die-hard fans.

Dan Vallone is principal at Polarization Risk Advisory, a research and strategy consulting firm focused on helping institutions manage risks from polarization. Dan is a former Army officer.

Image:Wikimedia