Britain’s Strange Defeat: The 1941 Fall of Crete and Its Lessons for Taiwan

Editor’s Note: This is the first in a running series of essays by Iskander Rehman, entitled “Applied History,” which seeks, through the study of the history of strategy and military operations, to better illuminate contemporary defense challenges.

[I]t remains astonishing to me that we should have failed to make Suda Bay the amphibious citadel of which all Crete was the fortress. Everything was understood and agreed, and much was done; but all was half-scale effort. We were presently to pay heavily for our shortcomings.”

– Winston Churchill, reminiscing on the loss of Crete and its immense natural harbor, Suda Bay.

In the early morning hours of May 20, 1941, screaming swarms of German Messerschmitts and Stukas suddenly materialized in the cloudless cerulean skies over Crete. Ferociously strafing and dive-bombing the anti-aircraft batteries of the island’s sleep-addled defenders, they were closely followed by a rumbling phalanx of Dornier 17 and Junker 88 bombers. Behind this flew a veritable airborne armada — 70-odd gliders filled with troops from the Seventh Airborne Division’s Storm Regiment and wave upon wave of lumbering Junker 52s crammed to the gills with nervous young paratroopers. For Gen. Bernard Freyberg — the highly decorated commander of Crete’s 32,000-strong garrison of British, Australian, and New Zealander troops, supplemented by close to 10,000 Greek soldiers — there was little cause for undue alarm. Plied with a steady stream of Ultra intercepts, the burly New Zealander had known for weeks that the Germans were preparing an invasion of the island. He retained something of a blithe self-confidence in his defensive preparations. So much so, in fact, that he calmly continued to enjoy his breakfast on his villa’s veranda, even as the bright blue sky above him grew increasingly pockmarked with Luftwaffe aircraft. Convinced that the bulk of the enemy’s invasion force would be ferried in by sea, where they would run afoul of the Royal Navy, the World War I veteran, like many of his fellow officers, remained dubious of the effectiveness of any large-scale airborne operation.

This dismissal of the viability of airborne assault against a well-entrenched position was largely shared in London, although some remained confused as to why Freyberg appeared to remain so focused on the threat of seaborne invasion when all intelligence clearly pointed to the prime vectors of an attack coming from the air. As we shall see, these key differences in threat prioritization and intelligence analysis would later prove critical. Nevertheless, and notwithstanding these early differences in opinion, the mood of the defenders on the morning of battle remained relatively buoyant. Indeed, only a few weeks earlier, Prime Minister Winston Churchill, had, in a moment of scrappy optimism, confided that while everything should be done to enable the “stubborn defense” of such a critically positioned island stronghold, Britain’s unerringly precise forewarning of German plans would also provide an unexpectedly “fine opportunity for killing the parachute troops.” On May 9, the Chiefs of Staff Committee, in a telegram to the commanders-in-chief in the Middle East and Mediterranean, had relayed their own singularly sanguine assessment of the looming conflict’s outcome: “So complete is our information that it appears to present heaven sent opportunity of dealing enemy heavy blow [sic]. It is now question of preparing subtle plan calculated to inflict maximum losses upon enemy.”

Over the course of the next few days, however, this stolid sense of confidence would progressively dissipate, to be replaced by one of bafflement and anguish, as the numerically superior defenders were first overwhelmed, then completely overrun by Germany’s assault. Despite suffering appalling levels of casualties at the hands of vengeful Cretan villagers and Commonwealth forces, thousands of German troops were shuttled across the Aegean onto Crete from newly enlarged or developed aerodromes on the freshly conquered Greek mainland. Fighting their way through thick olive groves and over craggy, dust-choked hills, these lightly armed paratroopers battled fiercely to secure permanent lodgments at key Cretan airfields such as Maleme, before finally establishing the requisite bridgehead allowing for their uninterrupted reinforcement by air. From that moment on — and largely thanks to the protective bubble proffered by the Luftwaffe’s dominance of the air — an incessant flow of battle-hardened German mountain troops poured into Crete, at one stage landing at a rate of 20 troop carriers per hour (each of which could carry approximately 20 people and four equipment containers). Over the course of a little less than two weeks, the Axis found themselves in full control of one the most strategically positioned territories in the Mediterranean, with Crete’s garrison forces either killed, captured, or hastily evacuated to British-controlled Egypt by sea. Coming after a series of bruising retreats, whether from Dunkirk in June 1940, or from the Greek mainland in late April 1941, the fall of Crete constituted a severe blow to British morale — all the more so because of its largely unexpected character, given London’s pre-existing assumptions.

And yet this strange defeat remains a remarkably underexplored historical case study in the fields of security studies and defense analysis. This is somewhat surprising, given its apparent educational value and strategic relevance to some of the most pressing contemporary military challenges in the Indo-Pacific theater.

Naturally, one cannot view this episode in isolation. As in any future hypothetical clash of arms in-between the United States and China and centered on contesting island territories ranging from the Senkakus, Thomas Shoal, or Taiwan, the 1941 battle for Crete can only be adequately analyzed within the context of a more protracted struggle and a broader campaign theater. The tragedy of Crete constituted but one grim chapter within the multi-year attritional contest between the Axis powers and a newly isolated British Empire for control of the Mediterranean basin in the wake of the fall of France. Its study reminds us of the importance of cartographic familiarity, of logistics, and for sea powers to think — as Nicholas Spykman famously noted — in “terms of points and connecting lines dominating an immense territory.” The strategic value attached by competing actors for the control of various Mediterranean islands, archipelagoes or islets — from Sicily to Malta or Karpathos — becomes self-evident when these same territories are viewed through the hard prism of logistical shipping and resupply. Even more so when one puts oneself in the shoes of cognitively overwhelmed defense planners struggling to mentally overlay shipping convoy routes, combat aircraft radii, and subsurface interdiction campaigns across an increasingly cramped, crowded, and contested maritime space. The battle for Crete thus formed an integral sub-component of a much broader campaign for theater dominance, a series of tightly interlocking conflicts ranging from the scorching deserts of North Africa to the snow-capped peaks of Thessaly.

The 1941 Cretan campaign also provides us with an interesting example of how, on occasion over the course of a protracted war, each power’s leadership can fundamentally misinterpret their adversary’s overarching intentions and grand-strategic orientation. Germany wished to shield its southward flank prior to the launching of Operation Barbarossa against the Soviet Union, as well as its precious Romanian oilfields. Meanwhile, following the evacuation of its forces on mainland Greece, Britain was committed to the forward defense of Egypt, the hub from which many of its empire’s logistical spokes radiated. Eyeing Crete, each party was convinced the other would use it as stepping-stone for renewed offensive operations and long-range airborne interdiction. Hence, each side engaged in their own form of motivated reasoning, driven primarily by what Carl von Clausewitz would have termed negative aims, and viewed possession of the large island as critical to their defense.

And last but not least, Britain’s Cretan debacle reminds us of the enduring truth of Helmuth von Moltke’s famed adage: “no plan of operations reaches with any certainty beyond the first encounter with the enemy’s main force.” When engaging in contemporary operational contingency planning for an assault on Taiwan, it behooves us to examine every potential axis of attack — including those that are less frequently examined than gray-zone subversion, a putative blockade, or seaborne invasion. All while recognizing that, in reality, in the grim event of a full-scale invasion of Taiwan, elements of all these approaches would most likely be employed by the People’s Liberation Army in tandem.

The Battle of Crete

The German invasion of Crete constitutes a pivotal moment in the annals of warfare. Indeed, it constitutes the first division-sized airborne assault. It fully succeeded in its overarching objectives despite the almost wholesale destruction of its lightly defended convoys of seaborne reinforcements at the hands of the Royal Navy. During its earlier campaigns in Western and Northern Europe, the Third Reich had employed paratroopers in a relatively ancillary and piecemeal fashion, tasking smaller bodies of these soldiers with the sabotage or capture of select enemy infrastructure such as bridges, airfields, and — most famously — the sprawling Belgian fortress of Ében-Émael in May 1940. From the moment of their inception, there had been vivid debates within the Nazi military establishment as to how these freshly designed airborne units should be deployed, with some officers arguing that their role was primarily to engage in small-unit disruptive actions behind enemy lines, and others urging the High Command to project them en masse in large-scale vertical envelopment operations.

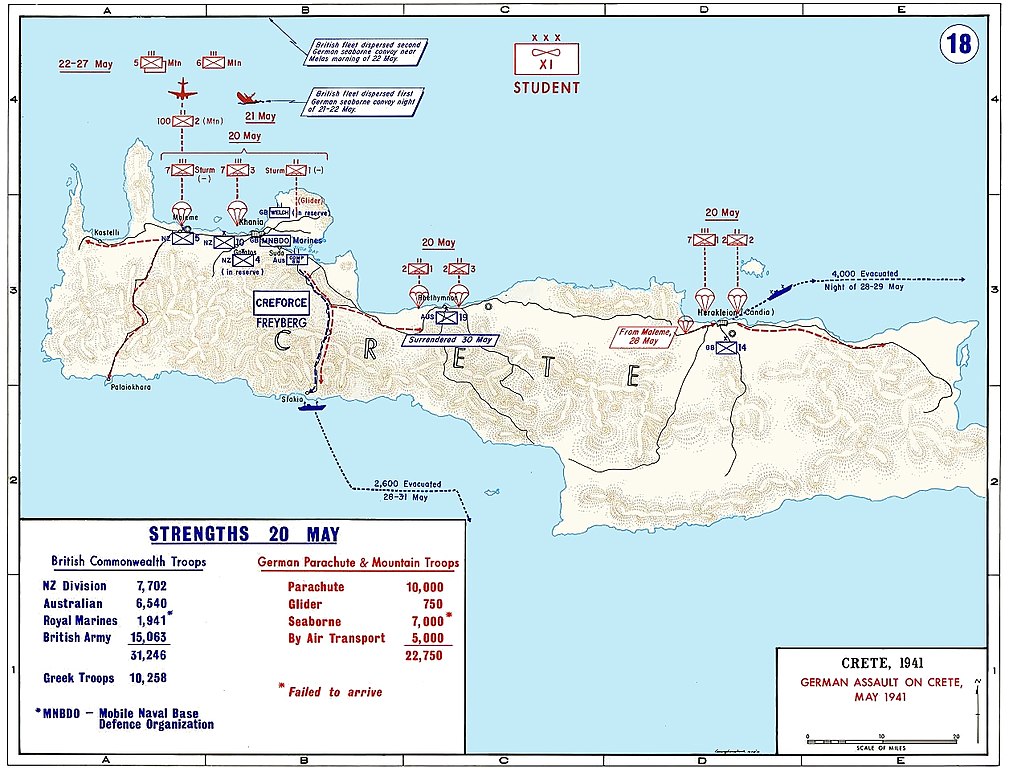

The German Assault on Crete (Source: West Point)

The German Assault on Crete (Source: West Point)

The Oberkommando der Wehrmacht’s decision to greenlight the audacious recommendations of Generaloberst Kurt Student, the Luftwaffe’s great pioneer of airborne operations, and launch Operation Mercury thus came after much internal debate and prevarication. While some leading German officers had expressed concern over the potential diversion of troops away from the herculean preparations for Operation Barbarossa later that year, others had suggested postponing the invasion of Crete in favor of a mass airdrop over the equally strategic British island bastion of Malta. All recognized, however, that the spearhead of any invasion of either of these territories would have to be projected by air, rather than by sea. Indeed, whereas the Royal Navy still possessed a clear quantitative and qualitative edge over its Italian and German foes in the Mediterranean, the Royal Air Force had suffered grievous losses (in addition to the loss of much of its air-basing infrastructure) during the frenetic British evacuation of mainland Greece earlier that year. Over the course of that retreat, 209 aircraft were lost — 72 in combat, 55 on the ground, and 82 destroyed to prevent their capture and use/cannibalization by the Germans. Following the relocation of most of the surviving aircraft to the North African theater, Crete was left with only a half-squadron of Hurricanes and a few other obsolescent aircraft. Moreover, the island was not only surrounded by a ring of Axis air bases, but also situated at the extreme edge of the combat radius of British fighters operating out of Egypt. As a result, the Luftwaffe now enjoyed a clear aerial superiority across the Eastern Mediterranean.

Initially somewhat reluctant, Adolf Hitler ended up approving Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring and Student’s brazen concept of operations, validating the idea of a division-sized airborne assault. This grudging concession was caveated by his insistence on expanding the number of target drop-zones, and on ferrying in supplementary reinforcements by sea, so that the beleaguered Allies would not be able to rapidly concentrate their forces to overwhelm the first waves of assailants. By combining amphibious landings with airborne operations, the German attackers would, the Führer observed, have “more than one leg to stand on.”

If Hitler and the Nazi High Command had possessed a fully accurate picture of the order of battle, however, they probably never would have embarked on such a risk-laden venture. Indeed, German intelligence had failed to detect a number of well-camouflaged enemy positions and arms depots, and until the very eve of the operation they had grossly underestimated the number, equipment, and morale of the island’s defenders and local inhabitants. Operating under the assumption that the British garrison on Crete amounted to only 5,000 men, the Abwehr also appeared convinced that the traditionally anti-monarchist Cretans would welcome their new German overlords. In reality, the garrison was over eight times that size, and the local population, from village housewives to local priests, attacked the bewildered Nazi paratroopers en masse and with a murderous intensity, wielding antiquated hunting rifles and bludgeoning them to death with farming tools as soon as they first started landing amid the island’s sun-scorched fields and villages.

In addition, the Abwehr remained unaware of the fact that many of the details of their military preparations had already been compromised by London’s decryption of German communication ciphers through Ultra — the codename given to the intelligence gleaned from the cracking of the Enigma machine over the course of 1940. And yet Freyberg — a prisoner to his own preconceived notions and prejudices on how an island seizure campaign would unfold — repeatedly failed to capitalize on this marked informational advantage over his Axis opponents. The intelligence intercepts clearly indicated that any seaborne invasion would only occur in the form of a second wave and once a secure air bridge had been established. Yet instead of prioritizing either the defense or preemptive destruction of the island’s three main north coast airfields at Heraklion, Maleme, and Rethymno, Freyberg chose to implement what amounted to a “damaging compromise both in the disposition of his troops and in his operational orders,” deploying a large number of soldiers seaward to fend off the amphibious assault he still believed would comprise the main thrust of the German invasion force.

Over the next 12 days, a ferocious battle would be waged across the 160-mile-long and 40-mile-wide island. Tangled in foliage or snared in tree branches, the first flock of assailants made for easy prey. One particularly unlucky group of paratroopers drifted right on top of the New Zealand 23rd battalion’s headquarters, whose officers calmly began shooting them down without even rising from their seats. By the end of the first day, given the staggering number of casualties (close to 2000), it looked as though the invading force was on the verge of complete annihilation. Consumed with fears of ignominious failure, German commanders began to contemplate a complete abandonment of the mission. Over the next few hours, however, additional waves of paratroopers eventually succeeded in securing, with the aid of heavy air support, the airfield of Maleme — a turning point in the conflict which then allowed for a steady influx of German mountain troops, light artillery, and motorcycle troops (the latter were highly effective in ranging across the dirt roads that wound through the island’s crenellated terrain).

By June 1, the Germans had succeeded in gaining full control of the island, and the last remaining Commonwealth forces surrendered. In a repeat of its heroic fighting retreats from Dunkirk or mainland Greece, the Royal Navy succeeded yet again in evacuating thousands of troops, all while under heavy aerial bombardment. Yet although 18,000 Commonwealth soldiers were ferried to safety, another 11,000 men found themselves stranded on the island and condemned to years of grim captivity. A few hundred slunk their way into the beetling crags and deep, shadowy ravines of the White Mountains, where they were sheltered by courageous Cretan villagers. While many were subsequently captured, some succeeded in evading German hunting parties and were later evacuated to Egypt by submarine. A small, but brutally effective, minority lent their efforts to those of the Special Operations Executive and of the fabled Cretan resistance, waging relentless guerrilla warfare on the island’s Nazi occupiers until its eventual liberation in 1945.

During the desperate evacuation, the Royal Navy’s extant surface fleet in the Mediterranean was nearly crippled by the loss of three cruisers and eight destroyers, along with over 1,800 sailors, and the savage goring of 17 additional frontline warships, such as the HMS Formidable, an aircraft carrier. Fighting to fend off hundreds of Axis fighters and bombers with perilously low levels of anti-aircraft ammunition and virtually no air support, British ships could only reliably conduct evacuations under cover of darkness. Meanwhile, with German squadrons able to refuel and rearm from neighboring air bases at their leisure, up to 462 Luftwaffe aircraft were deployed in continuous rotating sorties against Royal Navy vessels, whose crews, stretched to the very limits of their endurance, often found themselves forced to remain at their battle stations for over 48 hours at a time. One destroyer, the HMS Kipling, which miraculously emerged unscathed from the Cretan campaign, was thus swarmed by over 40 aircraft that targeted it with more than 80 bombs over the course of just four hours. At one point during the evacuations, the British Admiralty, pointing to their rapidly mounting losses, asked Adm. Andrew Cunningham, the commander-in-chief of the Mediterranean Fleet, whether it was time to beat a hasty retreat. To this, the doughty seaman famously responded, “It takes the Navy three years to build a ship but it would take three hundred years to build a new reputation. The evacuation will continue.” At the conclusion of their heroic evacuation efforts, 59 percent of the British fleet in the Mediterranean had either been sunk or seriously damaged by German airpower. Yet Germany’s startling victory had not been wholly without cost either. Of the approximately 22,000 men who took part in the invasion of Crete, there were close to 6,500 casualties, with 3,774 of these either killed or listed as missing in action. Many of these, as mentioned earlier, had been slain within the first 24 hours of the invasion. 350 aircraft, including one third of the Luftwaffe’s Junker transport planes, had been shot down — and Germany had yet to fully replace these losses by the time of the abortive Stalingrad airlift in November 1942. Meanwhile, Hitler — chastened by the operation’s pyrrhic toll — privately told Student over coffee at his Iron Cross awards ceremony that he would never again greenlight such a large-scale airborne operation, adding that Crete had “proved that the days of the parachute troop are over. The parachute arm is one that relies entirely on surprise, but the surprise factor has now exhausted itself.”

Lessons and Insights for Taiwan

At a time when U.S. military planning is consumed with the challenges of safeguarding another critically situated, mountainous island territory from invasion, a nuanced analysis of the factors behind the British Empire’s failure to provide for Crete’s adequate defense can provide U.S. and allied defense intellectuals with a number of instructive insights. Indeed, one can draw certain rough parallels between such past struggles for primacy over the Mediterranean and the current state of naval competition across some of the Indo-Pacific most heavily trafficked — and contested — waterways. In many ways, the South China Sea has emerged as the “Asian Mediterranean,” or middle sea, with Taiwan occupying a position athwart critical sealines of communication not so dissimilar to that of Sicily or Crete during World War II, or of Malta during the late Renaissance.

Moreover, evidence would suggest that the People’s Liberation Army, for its part, clearly sees the value of engaging in such exercises of applied history — particularly when it comes to the painstaking scrutiny of past archipelagic or island seizure campaigns, from the battle of Guadalcanal to the Falklands War. Meanwhile, contemporary sinologists have drawn attention to the critical role that Beijing’s steadily expanding airborne capabilities are slated to play in a number of China’s evolving concepts of operation — whether aimed directly at Taiwan or at smaller contested islets in the South and East China Seas. It would therefore behoove historically minded defense planners to channel some of their intellectual efforts into building out an exhaustive analytical repertoire of past instances of maritime invasion — and especially those that drew on a mixture of sea and airborne assets.

The Cretan campaign of 1941 remains illuminating with regard to the contemporary defense of Taiwan for three main reasons. First, it reminds us of the decisive role Chinese airpower would play in any invasion of Taiwan, and of the urgent need for Taipei to invest more heavily in a multilayered, resilient, and mobile air defense network. Second, it highlights the criticality of robust communication networks, of mission command, delegated decision-making, and general tactical responsiveness when countering large-scale airborne operations. And third, it casts an unfriendly light on the challenges inherent to playing an away game against an adversary operating on its own interior lines, emphasizing the importance of establishing a more geographically dispersed and logistically sustainable basing architecture in the Indo-Pacific.

Chinese Airpower and Taiwanese Air Defense

The battle of Crete was won by German airpower. With only limited air defenses and a handful of forward-stationed aircraft, the Commonwealth and Greek garrison forces on Crete were continuously subjected to heavy and psychologically demoralizing aerial attack, with the Luftwaffe carpet-bombing their positions in unbroken rotations, strafing troops and lines of communication with impunity. As Cunningham later observed in his memoirs, it rapidly became painfully evident that Britain’s localized naval advantage could not offset its deficiencies in airpower, or its limited anti-aircraft magazine depth. As a result, he glumly noted, “with our [Britain’s] complete absence of air cover, the Luftwaffe, by sheer weight of numbers, were having it practically their own way … gunfire from the best of ships cannot deal with aircraft which an officer who was there likened to a swarm of bees.” These difficulties — the absence of proper air support and the Royal Navy’s shell hunger — were compounded by the peculiarities inherent to Crete’s topography, he added, with its towering southward-facing mountain barrier, which sloped in many places directly into the sea, meaning that all major ports and airfields were situated on the northern coast of the island, “within easy range of enemy aerodromes.” “From the point of view of defense,” he wryly noted, “it would have suited us much better if the island could have been turned upside down.” Up until the end of his life, Cunningham was to remain firmly convinced that “three squadrons of long-range fighters and a few heavy bombing squadrons would have saved Crete.” Unfortunately for Crete’s defenders, however, those squadrons were simply not available at the time — or at least not within a viable operational radius. Those few Hurricanes that were belatedly sortied from bases in Alexandria were thus retrofitted with external fuel tanks, something that rendered them both more sluggish and vulnerable in aerial combat as the “armor plating behind the seats had to be removed and ammunition reduced to compensate for the weight of the extra fuel.” And for all their gallant efforts, the Free French and British fighter pilots who flew to the island’s defense were soon overwhelmed by clouds of German Messerschmitts who mobbed them like a “horde of hawks on a single sparrow.”

Present-day Taiwan faces an equally, if not even more daunting form of airpower asymmetry. Its small air force of approximately 400 legacy fighters is hopelessly outnumbered by that of China, which is adding ever more fourth- and fifth-generation aircraft to its inventory, all while expanding and hardening its southeastern airfields at breakneck speed. And while much focus within the U.S. defense commentariat has (rightly) been laid on Beijing’s shipbuilding prowess, one should not overlook the troubling fact that the People’s Liberation Army Air Force is now also well on track — if it sustains its current rhythm of aircraft production — to be the largest air force in the world. In addition to this marked air imbalance, Taiwanese defense planners should also take into account the People Liberation Army Rocket Force’s increasingly robust inventory of cruise and ballistic missiles, which has more than doubled in size over the last three to four years. These missiles would play a central role in the opening phases of any “joint firepower strike campaign” directed at Taiwan and its air force, raining down on its fixed air defenses, airfields, and munition depots, while destroying any aircraft not concealed or parked within hardened shelters. As in Nazi Germany’s invasion of Crete, Beijing can only generate the follow-on conditions for a successful invasion of Taiwan by decisively wresting control of the air away from the island’s defenders. Rather than expending large amounts of resources in acquiring additional F-16s, or even F-35s— which, like the beleaguered British Hurricanes defending Crete, would soon find themselves hopelessly outnumbered — Taipei should focus on building out a more multilayered and survivable “guerrilla air defense” network. This would seek to better combine long-range air defense systems with shorter-range air defense systems along with vertical take-off and landing unmanned aerial vehicles, loitering munitions, and man-portable air-defense systems. In addition to investing more heavily in passive defenses (such as concealing and hardening) and rapid runway repair kits, priority should be given to more highly mobile, concealable, and attritable air defense systems over expensive fixed surface-to-air batteries such as the Patriot PAC-3, which — while highly effective — takes a long time to set up and redeploy. For a relatively modest amount of money, Taiwan could thus invest in thousands of truck-mounted containerized surface-to-air missiles that could then be dispersed throughout the island, magnifying the targeting challenges for China’s air force and greatly extending the difficulty and duration of its air defense suppression campaign.

Finally, Taiwan should invest more heavily in its counter-strike capabilities. During the Cretan campaign, British forces suffered greatly from their inability to disrupt the tempo of Luftwaffe sorties by decisively striking at their points of origin, i.e., the string of newly built or acquired airfields on the Greek mainland or on neighboring islands. In line with Taipei’s most recent Quadrennial Defense Review and its “overall defense concept,” which stress the need to “construct asymmetric capabilities to strike the operational center of gravity and key nodes of the enemy,” the Taiwanese armed forces should devote more resources to the indigenous development and fielding of long-range cruise missiles such as the Hsiung Sheng II, along with their associated targeting infrastructure. These can then be used to hit back at Chinese runways, command centers, and embarkation points.

The Importance of Communications and Initiative in Counter-Airborne Operations

For Student, one of the great tactical virtues of airborne operations was their ability — through the effects of speed and surprise — to generate confusion and disarticulation among more sluggish and statically arrayed opposing forces. As he was later to note in his memoirs,

airborne troops could become a battle-winning factor of prime importance. Airborne forces made three-dimensional warfare possible in land operations. An adversary could never be sure of a stable front because paratroops could simply jump over it and attack from the rear when and where they decided. There was nothing new about attacking from behind of course, such tactics have been practiced since the beginning of time and proved both demoralizing and effective. But airborne troops provided a new means of exploitation and so their potential in such operations was of incalculable importance. The element of surprise was an added consideration; the more paratroops dropped, the greater the surprise.

Despite their quantitative superiority and foreknowledge of the German attack, Crete’s defending forces revealed themselves all too vulnerable to this form of vertical envelopment and dislocation. First of all, their lack of a proper mobile reserve in the form of trucks and Bren gun carriers made it challenging for Commonwealth forces to swiftly and decisively mop up successive waves of paratroopers, which soon spread, in accordance with Student’s own tactical predilections, like “drops of oil” across the map. But even if Freyberg had established such a rapid reaction force, its response time would have been negatively impacted by the sorry state of infrastructure on the island, with one visiting officer griping in the weeks leading up to the invasion that “not even the most elementary preparations had been made” to improve road connectivity between Crete’s main ports and airfields. And last but not least, as the great military historian Antony Beevor has rightly noted, the “ramshackle” state of the defenders’ communications proved to be their greatest weakness. Field telephones depended “on wires run loosely along telegraph poles” and were thus highly “vulnerable to bombardment and to paratroopers dropping between headquarters.” Adding insult to injury, the woefully insufficient number of wireless sets and signaling lamps meant that once the Luftwaffe had snuffed out the phone lines, there was little way for the geographically dispersed defenders to mount any form of coherently coordinated response to the ever-growing number of enemy incursions.

Present-day China attaches a similar importance to the operational benefits of shock and surprise when conducting airborne assault operations. Much like Student, the People’s Liberation Army portrays the close integration of amphibious, air assault, and airborne forces within the context of a Joint Island Landing Campaign aimed at Taiwan as constituting a “three-dimensional landing operation.” Meanwhile, the 2006 Science of Campaigns describes the disruptive and chaos-inducing role of the rapidly modernizing People’s Liberation Army airborne corps during the critical initial phases of an invasion in the following terms:

[One must] immediately initiate attacks against the predetermined targets, taking advantage of the situation when the enemy’s (assessment of the) situation is unclear, they cannot organize effective resistance in time and the counter airborne landing troops have not yet arrived, to quickly seize and occupy objectives, actively complement landing force operations and accelerate the speed of the assault onto land, ensuring that the assault on land succeeds in one stroke.

One of the greatest operational benefits of airborne assault forces, the Science of Campaigns then goes on to note, is their ability to add to the general fog and friction of war, confusing and demoralizing the defender, and creating favorable conditions for follow-on activities “when the battlefield posture is jagged and interlocking, and the situation is complicated and confusing.” As Taiwanese forces shape and posture themselves to respond to such challenging combat contingencies, they should ensure they do not find themselves in the same position as Crete’s defenders in 1941, incapable of counterattacking rapidly and effectively within a logistically deteriorated and communications-degraded battlespace. Like Crete, Taiwan is a topographically challenging combat environment — its mountainous terrain provides ample opportunities for irregular warfare and asymmetric defense, but it also renders the island democracy more dependent on a few key transport arteries and logistical bottlenecks that would undoubtedly be targeted in the opening phases of a Chinese invasion. So would its main power plants. Unfortunately, imported coal, gas, and oil still comprise 82 percent of Taiwan’s power generation, something that renders its energy grid acutely vulnerable to kinetic, cyber, or electromagnetic attacks. Taiwan’s digital infrastructure and communications network could prove equally brittle, with over 97 percent of its global internet traffic carried via a handful of easily severed undersea cables.

In order to offset these clear vulnerabilities, Taiwanese forces should enhance their ability to “fight dark” within contested, scrambled, and chaotic environments, equipping counter-airborne assault platoons with all-terrain vehicles, shortwave radios, man-portable air defense systems, first-person-view drones, and shoulder-fired anti-armor systems such as Javelin. Perhaps most importantly, this will need to be accompanied by a genuine transformation in Taiwanese military culture and operational practices, as these small units would be required to operate largely autonomously for extended periods of time. This will require a broader shift away from one recent report rightly describes as a “highly centralized [Taiwanese] command and control structure that does not empower units to make tactical decisions,” and from sometimes overly scripted military exercises. And while the Taiwanese army should certainly continue training to repel large-scale amphibious landings, more focus should be put on enhancing its capacity to conduct an “elastic denial-in-depth” campaign across the island and on countering other, more unpredictable forms of assault, disruption, and sabotage.

Washington’s recent decision to quietly expand the scale and scope of training activities with Taiwan, with greater numbers of Taiwanese ground forces being sent in regular rotations to train on American soil, could provide a welcome opportunity for both partners to collaboratively reshape certain overly rigid aspects of Taiwanese military culture. The fact, for instance, that a growing number of Taiwanese noncommissioned officers will reportedly now partake in “training observation missions” in the United States is a step in the right direction. Indeed, working to better train and empower Taiwan’s noncommissioned officer corps is critical to instilling a more horizontal culture of disciplined initiative, or mission command, across its armed forces. U.S. advisory forces based in Taiwan — which have begun increasing in number — can also discreetly help guide this cultural shift.

The Challenges of Playing an Away Game

Some of the most fascinating debates involving British grand strategy and military operations during World War II are to be found in the notes of the impassioned parliamentary debates following the fall of Crete. Fending off a barrage of critiques regarding the island’s woeful state of preparedness for an airborne invasion and the fateful consequences of Germany’s crushing dominance in the air, Churchill pointed to the difficulties of playing an away game against an adversary that now controlled most of southern Europe:

Anyone can see how great are the Germans’ advantages, and how easy it is for the Germans to move their Air Force from one side of Europe to another. They can fly along a line of permanent airfields. Wherever they need to alight and refuel, there are permanent airfields in the highest state of efficiency, and, as for the services and personnel and all the stores which go with them — without which the squadrons are quite useless — these can go by the grand continental expresses along the main railway lines of Europe. One has only to compare this process with the sending of aircraft packed in crates, then put on ships and sent on the great ocean spaces until they reach the Cape of Good Hope, then taken to Egypt, set up again, trued up and put in the air when they arrive, to see that the Germans can do in days what takes us weeks, or even more. … The decision to fight for Crete was taken with the full knowledge that air support would be at a minimum, as anyone can see — apart from the question of whether you have adequate supplies or not — who measures the distances from our airfields in Egypt and compares them with the distances from enemy airfields in Greece and who acquaints himself with the radius of action of dive-bombers and aircraft.

The main “limiting factor,” the British prime minister went on to note, was not his country’s overall number of aircraft, but rather “transportation” — not so much “in the sense of shipping tonnage, but in the sense of the time that it takes to transfer under the conditions of the present war.”

In the event of a high-intensity conflict over Taiwan, the United States would face similarly daunting power-projection and sustainment challenges. With regard more specifically to airpower, China would be operating on interior lines and under the protective umbrella of its integrated air defenses, which, since its acquisition of the S-400, now extend well beyond the Taiwan strait. As of now, the United States has only two air bases from which its fighter jets can conduct unrefueled operations over Taiwan, while China has close to 40. Whereas China’s air force would be conducting sorties from coastal airfields positioned almost directly across the 100-nautical-mile-wide Taiwan Strait, Kadena Air Base in Okinawa — currently the largest U.S. Air Force base in the Indo-Pacific — is close to 450 miles from Taiwan. Just like Crete during World War II, it would greatly aid Taiwanese and U.S. defense planners if the island could be “turned upside down,” with its steep mountain range facing toward the Chinese mainland rather than in the opposite direction. Instead, Taiwan’s major semiconductor factories, power plants, highways, and population centers — 22 million of the country’s 23.5 million people — are all clustered in the western lowlands, right opposite the People’s Republic of China.

In order to offset China’s formidable inbuilt geographic advantages, the U.S. military will need to both increase its forward combat power and enhance its capacity for sustainment, as well as its resilience to disruption.

Recent successes in negotiating new basing arrangements — from Palau to the Philippines — offer the prospect of a more dispersed, resilient, and operationally “agile” regional force posture. Being able to one day, for example, permanently position aircraft in Northern Luzon, which is only 160 miles from Taiwan, could prove transformational in the event of conflict. In addition to expanding and diversifying its basing architecture in the region, the United States should also deepen, harden, and disperse forward-positioned munitions stocks and fuel-storage tanks, work to improve in-theater capabilities such as underway replenishment and at-sea reloading, and use allied shipyards in countries such as Japan and South Korea for in-theater maintenance and repair. And last but not least, it should encourage and assist Taiwan in stockpiling its own fuel, materiel, and munitions for a protracted conflict, with the full knowledge that — just as for the Royal Navy during the battle for Crete — it could prove exceedingly challenging to reinforce and resupply the island democracy once major hostilities have begun. Unlike the local Greek forces on Crete, it could transpire that Taiwan’s armed forces will have to defend their island largely by themselves — either for the duration of the campaign if an American administration less supportive of Taiwan decides not to intervene in its defense — or for a critical period during which the United States (and perhaps some of its regional allies, such as Japan) muster follow-on forces to come to its rescue.

The great Greek historian Polybius once caustically observed that there were two ways by which statesmen could improve the quality of their decision-making, either by going through the punishing process of their own trial and errors or by studying “those of others.” Making a similar point, albeit with his own characteristic bluntness, retired secretary of defense and Marine Gen. Jim Mattis once quipped that all military officers should study history, if only because “learning from others’ mistakes is far smarter than putting your own lads in body bags.” And indeed, applied history, provided it is done in a nuanced and discerning fashion, can greatly assist in this process of vicarious experiential learning. The loss of Crete was not only one of Britain’s most tragic defeats during World War II — it also seemed, in the eyes of many at the time, to be one of its most incomprehensible. After all, large-scale airborne assault operations had been deemed either too impractical or too dangerous. And indeed, such attempts at forcible entry remain rife with risk, as Russia’s bloody failure during the 2022 battle for Hostomel airport recently only made too clear. And yet one should never let preconceived assumptions about how an operation might unfold — or of what costs a determined adversary might be willing to bear — lull us into a sense of complacency, like the brave, but ultimately shortsighted Freyberg. The Cretan saga also serves as a useful reminder of how good intelligence collection and good intelligence analysis are two very different things. British and Commonwealth forces on Crete were provided with excellent and timely information on their adversary’s military plan of action, yet still chose to implement a defensive strategy that was overly linear in nature, under-resourced, and ill-tailored to the nature of the threat.

A few weeks after the defeat, in a memorandum to Gen. Hastings Ismay for the Chiefs of Staff Committee, Churchill privately excoriated Freyberg’s decision-making, noting that even if one made “allowances for the deficiencies” the commander had contended with in terms of munitions, materiel, and airpower, “the whole conception seems to have been of static defense of positions, instead of the rapid extirpations at all costs of airborne landing parties.” Part of the issue, he groused, was that British military commanders stationed at “Middle East HQ” had appeared to regard the defense of Crete as being a

tiresome commitment, while at the same time acquiescing in its strategic importance. No one in high authority seems to have sat down for two or three mornings together and endeavored to take a full forward view of what would happen in the light of our information, so fully given, and the many telegraphs sent by me and by the Chiefs of Staff.

Similarly, vacuuming up huge amounts of human, geospatial, signals, and imagery intelligence on China’s war making preparations is one thing, but making good use of this information to “take a good forward view” and anticipate the many ways by which the Chinese Communist Party, with its historic predilection for brinkmanship and subterfuge, may choose to conduct a major cross-strait operation, is another. In short, by learning from the 1941 fall of Crete and other underexplored episodes in military history, one can hopefully ward off the prospect of a similarly unwelcome form of strategic surprise.

Iskander Rehman is the Senior Fellow for Strategic Studies at the American Foreign Policy Council, and an Ax:son Johnson Fellow at the Kissinger Center. He can be followed on Twitter @IskanderRehman.