Even as Russian President Vladimir Putin and Chinese General Secretary Xi Jinping a were forming “a new epoch in relations” between their two countries, Russia was still planning for the possibility of nuclear war against China as late as 2014. Recently leaked Russian documents reveal contingencies for such a war against China in Siberia, including potential scenarios for the use of nuclear weapons against China.

Russian planning for a nuclear war with China may seem surprising in hindsight. After all, this was just two years before the two countries increased their number of joint military exercises, as part of a larger pattern of closer defense cooperation, and eight years before Beijing and Moscow announced their friendship had “no limits.” However, such plans are perfectly consistent with Russian threat perception and nuclear doctrine. Beijing and Moscow are historical rivals, with geopolitical competition between Russian and Chinese polities dating back to the 17th century. The Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China fought a border war in 1969, and Beijing later cooperated with Washington at the expense of Moscow from 1972 through the end of the Cold War. Members of the Russian foreign policy elite continued to perceive China as a potential threat into the 21st century, as these war plans indicate.

Moscow’s desire to maintain a nuclear option against China is consistent with its strategy. Russia faced a significant conventional inferiority vis-à-vis China, especially in the Russian Far East. Deploying intermediate-range nuclear weapons to Russia’s Eastern Military District, where they could reach Chinese military targets but not military or political targets in the United States or Europe, gave the Russian military credible options for blunting a Chinese invasion. Launching a limited nuclear strike to quickly degrade Chinese capabilities in an effort to terminate a war on terms favorable to Russia is consistent with Russian strategic thought on escalation management, which scholars typically studyas an aspect of Russian strategy in Europe.

In this article, we discuss Russia’s perception of a Chinese threat and strategies to neutralize it. Our analysis provides insights into under-researched and under-reported elements of Russian grand strategy and foreign policy. We start with a short but detailed description of the Russia-China rivalry, including its origins in the Russian Far East and its future prospects. We then outline potential Russian responses to a hypothetical Chinese invasion, explaining why Russia would want to consider a nuclear option, discussing potential conventional strategic options that provide the Russian military with an alternative response, and then tying these considerations to broader Russian nuclear doctrine.

The Sino-Russian Rivalry

Today, Russia and China describe their partnership as having “no limits.” However, the current partnership between Russia and China is a deviation from past relations. The two countries have engaged in competition and even fierce rivalry for centuries. This rivalry spans multiple polities and different regime types, including the Russian Empire, the Soviet Union, the Russian Federation, China’s Qing Dynasty, and today’s party-state.

Sino-Russian relations began with military conflict over tributary privileges in areas around the Amur River, culminating in battles centered on the Albazin fortress in 1685–1686 and the death of hundreds of combatants on each side. The Treaty of Nerchinsk in 1689 between Qing China and Romanov Russia marked the start of nonmilitary engagement. This relationship was based primarily on trading rights and agreements, without what we would describe today as formal diplomatic recognition. Russian envoys to China were considered tributary missions in official Qing records in accordance with the Sino-centric tributary system of international relations in place in East Asia at the time. Russia acquired large swaths of territory from China via the treaties of Aigun (1858) and Peking (1860) during the Century of Humiliation, when several Western imperial powers coerced China to sign predatory treaties.

A period of closer ties between China and the Soviet Union following World War II gradually eroded due to a combination of strategic, ideological, and status factors. By 1969, the Sino-Soviet split erupted into a border war along the Ussuri River between Manchuria and the Russian Far East. The Chinese eventually sided with the United States during several of the late Cold War’s significant events, including aiding American support for the mujahedeen in Afghanistan.

Relations between Moscow and Beijing improved after the Cold War. Russian Foreign Minister Yevgeny Primakov viewed China as critical to developing a balancing coalition against the United States. Mutual interest in combatting terrorism, resolving border disputes in Central Asia, and developing a multipolar world led to the formation of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization in 2001. Like many other post-Soviet intergovernmental organizations, however, the organization did not represent a binding commitment for its members.

Despite these growing ties, the Sino-Russian relationship was not as close as it is today. Moscow’s long-held mistrust of political and security elites from the Cold War, historical claims to territory in the Far East, and competing interests in Central Asia contributed to its suspicion of Beijing. Mutual mistrust, in particular, represented a major barrier to deepening cooperation, and both sides have actively sought to prevent similar issues from derailing the current partnership.

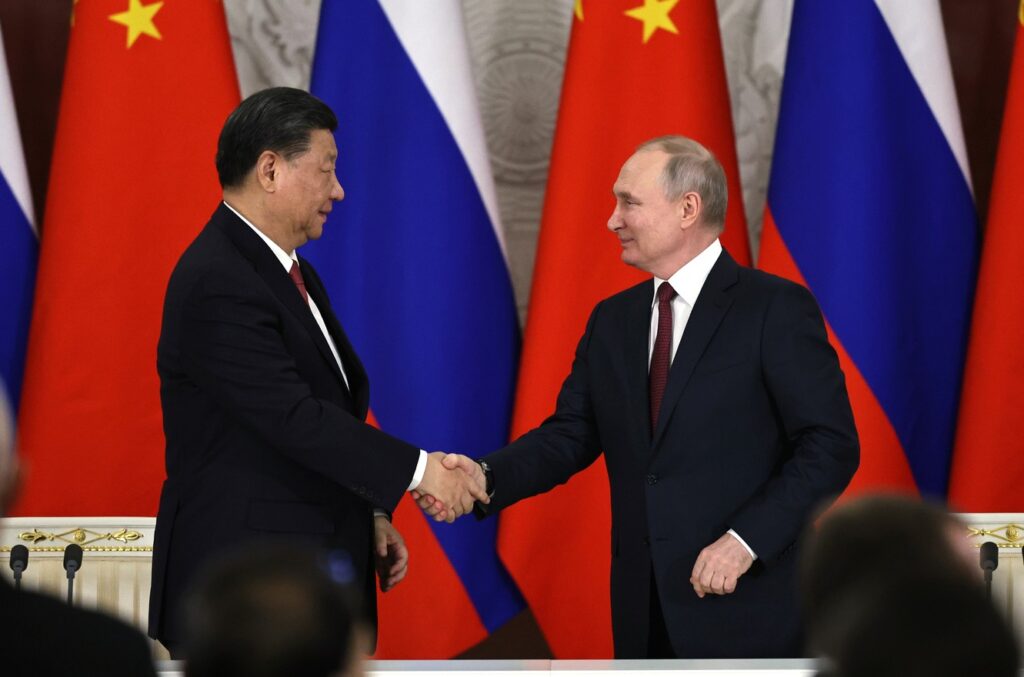

The coalescence of a Russia-China partnership largely occurred in the 2010s. Xi and Putin’s interpersonal relationship and shared interests in regime stability contributed to the partnership following Xi becoming general secretary and Putin’s return to the Russian presidency in 2012. In contrast to Beijing’s refusal to support Russia’s actions in Ossetia in 2008, as most of the Western world has ostracized Russia over Ukraine, China and Russia have expanded cooperation, in part because of Xi’s personal respect for Putin. Western sanctions against Russia after it annexed Crimea in 2014 drove Russia and China closer politically and economically, a phenomenon repeated after Russia’s 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Sino-Russian military cooperation also broadened after 2014, although the partnership lacks many of the advanced military cooperation practices of the United States and its European and Asian allies.

Will the Rivalry Ever Be Renewed?

The partnership is not guaranteed to endure. Russian leaders felt the threat of a Sino-Russian split was enough to warrant war planning even as relations improved following the Cold War. Several areas produced tension in the Russian-Chinese relationship before the emergence of the current partnership. These same areas could lead to the partnership’s eventual undoing. Specifically, fears of Chinese designs on the Russian Far East, competing claims for influence in Central Asia, and increasing Chinese interest in Arctic development could unravel the friendship without limits.

Several factors could erode the currently stable equilibrium in the Russian Far East. The region contains much of Russia’s mineral wealth and provides the basis for a significant amount of Sino-Russian trade, including a major pipeline. Beyond the potential for direct Chinese irredentism stemming from the effort to regain territory lost in the 19th century, continued Chinese in-migration into the region creates a source of tension.

Concerns about Chinese investment and land ownership prompted residents of the Irkutsk Oblast to start a petition in 2018 seeking to ban the purchase of land around Lake Baikal by Chinese investors. While the official stance of the Russian government is to downplay any possibility of conflict with China in the Russian Far East, this sparsely populated region has been the location where all past Sino-Russian confrontations have taken place. Russia’s territorial proximity to China in the region and their generally approximate power and status are among the risk factors for war that international relations scholars have identified.

Farther west, Russia and China are vying for influence in Central Asia. The former Soviet republics of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan are strategically important for Moscow and Beijing. Both want access to the region’s energy reserves and mineral deposits. The region also has significant security implications. Moscow and Beijing worry that regional groups linked to al-Qaeda or the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant could recruit from oppressed Muslim minorities in China and Russia.

Russia and China have avoided the most severe competition for influence over the past couple of decades, with Russia focusing on security influence and China on economic influence. However, future economic and security needs could erode this division of influence. Moreover, some have argued that Russia is a junior partner in the regional Sino-Russian relationship, creating tensions. Among the potential causes of war described in the Russian wargames were competition for natural resources, economic opportunities, and energy reserves in Central Asia.

Finally, China is increasing its investment in Arctic development and its military footprint in a region vital to Russian security. While the threat of competition in the Arctic is significantly lower than the potential for conflict in the Russian Far East and Central Asia, it still exists. Additionally, minor disagreements over the Arctic could exacerbate more serious tensions elsewhere.

Why Go Nuclear?

If relations collapsed and Russia and China found themselves on the warpath, Russia would face a conventional inferiority that is especially pronounced along the Sino-Russian land border. Russia deploys most of its military in the West, where forces can reach the front in Ukraine, react to a possible NATO intervention or invasion, and deal with the threat of separatist groups in the North Caucasus.

For the Kremlin, employing battlefield nuclear weapons offers a potential equalizer in the Far East. Russia could augment its defense by striking Chinese troops amassing in Manchuria. Russia could also strike vital transportation, communications, and energy hubs to degrade Chinese warfighting capabilities or force China to de-escalate the conflict.

China’s options to respond are limited. While China may have shorter-range weapons to strike strategic targets in the Pacific, it does not possess the low-yield battlefield nuclear weapons necessary to match a limited Russian nuclear strike. Instead, it could attempt further conventional strikes — potentially against continued Russian battlefield nuclear weapons use — or could escalate by striking Russia with its strategic nuclear forces. The latter would likely draw a strategic nuclear response from Moscow. Chinese strategic thought would suggest a strategic conventional strike as the most likely response, as Chinese doctrine historically eschews limited nuclear strikes due to a belief that escalation control is nearly impossible in nuclear conflict. However, China’s nuclear posture and arsenal have changed significantly over the past decade. Such nuclear restraint was consistent with Chinese strategy at the time of the wargames, but Chinese doctrine may be changing to one more open to limited nuclear war.

China’s limitations may make the use of battlefield nuclear weapons more likely. Russian leaders may perceive Russian escalation dominance, low-yield nuclear superiority, and conventional inferiority. The combination would incentivize limited nuclear use, as the Kremlin may see it as both effective and necessary.

Limited Strikes and Russian Nuclear Doctrine

According to a report in the Financial Times, Russian wargames planned for a potential Chinese invasion in the Russian Far East. These wargames included Chinese attacks in the Russian Far East and occasionally Chinese strikes through Kazakhstan against targets in Western Siberia and the Urals. Even during the latter scenarios, Russian military leaders seem to have expected the primary Chinese goal to be an invasion of the Russian Far East as an act of imperialist expansion to provide living space for China’s expanding population, satisfy nationalist irredentism, or create resource colonies to fuel an overheating Chinese economy. The third goal was of particular concern for Russian strategists, with some wargames focusing on an invasion after Russia refused Chinese demands for energy resources at a sharp discount.

At the onset of violence in the Russian Far East, wargame scenarios had China sending fake protesters to clash with Russian police, followed by saboteurs using the chaos to strike at critical security infrastructure. During the ensuing crackdown, China accused Russia of committing genocide against ethnic Chinese residents of the Russian Far East and increased defense production and deployments along the border in preparation for a larger invasion.

The authors of the Financial Times article noted that the Chinese tactics used in these scenarios resembled Russian tactics during its 2014 invasion of Ukraine. Additionally, concerns about Chinese expansion for living space reflect Russian experiences in World War II, when Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union in its quest for Lebensraum — living space for Germans taken from the Slavic and Jewish populations of Eastern Europe.

While Chinese tactics and motivations differed in various scenarios the Russian military considered, most involved some kind of quick Chinese strike into Siberia or the Far East and the threat of a larger Chinese invasion. Russia considered nuclear use to prevent this follow-on attack.

Nothing in known Russian nuclear doctrine states that Russia will use nuclear weapons when facing invasion from a conventionally superior opponent. But maintaining the option to use nuclear weapons if Russian political leaders believe it is strategically beneficial is a critical component of Russian doctrine.

Russian declaratory policy states that nuclear weapons are the ultimate guarantor of Russian sovereignty and territorial integrity. Russian strategic thought generally considers nuclear weapons potential tools for defeating a large invasion, such as the follow-on invasion from China that is the subject of leaked Russian plans. Writings in Russian professional military journals, where current and retired Russian officers, strategists, and security officials discuss and debate strategic issues, also discuss the possibility of using limited nuclear strikes when an adversary’s conventional forces pose a significant threat to Russian territorial integrity or the survival of the regime.

Should Russia decide to use nuclear weapons, the primary goal of a nuclear strike would be to blunt a Chinese invasion and potentially force China to end the war on terms favorable to Russia. Chinese military capabilities, including troops massing in Manchuria, naval assets, and air forces, are likely targets. Degrading these capabilities would reduce the extent of Russia’s conventional inferiority and improve the likelihood of the Russian military defeating the Chinese invasion.

Other targets could include critical Chinese infrastructure near the invasion area. Russia may use a limited nuclear strike to destroy important transportation networks, weapons storage, energy resources, communications systems, or other pieces of infrastructure needed for a successful Chinese invasion.

This use of a limited nuclear strike is consistent with Russian strategic thought on escalation management. Some experts and policymakers refer to the concept of escalation management as escalate to de-escalate, although there is significant debate in scholarly circles about the accuracy and appropriateness of the term.

Russian strategists consider a quick limited nuclear strike as a potential tool to contain escalation by degrading an enemy’s ability to increase violence and deterring vertical or horizontal escalation through the threat of further strikes. Russian leaders see such escalation management strikes as necessary for keeping conflicts at a level of violence that is too low to threaten Russian sovereignty or to terminate a war quickly on terms favorable to Russia.

Similar strategies have been noted as a potential Russian response to a war with NATO in the West. Russia has several weapons that it could choose for these missions, including Iskanders stationed near Russia’s border, nuclear-capable bombers in Siberia and the Far East, or low-yield sea-based nuclear weapons deployed with the Pacific Fleet in the Sea of Okhotsk.

Conventional precision strike capabilities provide Russia with a non-nuclear alternative for such a strike. Russian strategic thought includes strong considerations for using precision strikes against critical infrastructure to blunt an enemy invasion. Either limited nuclear use or a series of conventional precision strikes would be consistent with Russian doctrine. The ultimate decision to go nuclear or stay conventional lies with Russia’s political leadership and their beliefs, whether correct or not, about which option gives them the greatest chance of maintaining Russian territorial integrity.

Conclusion

Russian plans for a war with China are consistent with Russia’s historical perception of a Chinese threat. While Beijing and Moscow currently enjoy a strong partnership, the Sino-Russian relationship is marked by a history of interstate rivalry and periodic wars along their shared periphery. Russia and China may enjoy this partnership well into the future, but this is not guaranteed. Areas of potential tension, including Central Asia, the Russian Far East, and the Arctic, could erode the current partnership and renew the rivalry between China and Russia.

Nuclear use is not guaranteed, but a Russian limited nuclear strike is possible if a renewed Sino-Russian rivalry devolved into war. Limited nuclear strikes against Chinese military forces or critical infrastructure would be consistent with Russian thought on escalation management.

Going nuclear would pose significant risks for Russia. Russian leaders could miscalculate a strike’s effectiveness or incorrectly assess the risk of a Chinese nuclear response. The decision to employ nuclear weapons would be a political one. Russian leaders would weigh the expected risks and rewards of a strike, as well as those of a non-nuclear response, and select what they perceive as the best option.

John C. Stanko is a doctoral candidate in political science at Indiana University. Thon primarily engages in foreign policy analysis of highly centralized states, with a focus on Eurasia, broadly defined.

Spenser A. Warren is a postdoctoral fellow in technology and security at the University of California Institute on Global Conflict and Cooperation. He holds a Ph.D. in political science from Indiana University Bloomington.

CORRECTION: A previous version of this article misidentified the Chinese dynasty that signed the Treaty of Nerchinsk. It was the Qing, not the Ming Dynasty.

Image: Wikimedia