How Advanced Is Russian-Chinese Military Cooperation?

There is widespread consensus among analysts that, although Russia and China have been moving toward closer cooperation through the entire post-Soviet era, the trend has accelerated rapidly since 2014. The specter of a Russian-Chinese partnership is deeply threatening to the United States, not only because it makes U.S. military planning more challenging, but also because it raises the possibility of two formidable adversaries joining forces to counter U.S. interests and potentially working in concert to attack U.S allies.

The strategic partnership, first established in 2001, was boosted in the mid-2010s by Russian leaders’ belief that Russia needed to seek out alternative relationships to survive its sudden confrontation with the West. China was the obvious candidate because it had a suitably large economy, was friendly to Russia, and was not planning to impose sanctions in response to the 2014 invasion of Ukraine. Xi Jinping’s rise to power also has contributed to a deepening of the partnership, as China under Xi shares President Vladimir Putin’s concern with regime security and the two leaders increasingly align on issues of global and regional security. Moreover, the two countries had a record of cooperation dating back to the early 1990s that could serve as a basis for expanded cooperation.

This article summarizes a CNA report that tested this proposition. To do so, we focused on measuring military cooperation, specifically on military diplomacy and other political aspects of the defense relationship, military-technical cooperation, and exercises and joint operations. Our goal is to provide an analysis of the dynamic of the cooperative relationship in the period since 2014, including a discussion of what the relationship allows the two partners to accomplish together that they cannot do alone, and what analysts can infer about where this bilateral relationship is headed.

Using a comprehensive collection of Russian- and Chinese-language media reporting and technical articles on bilateral military ties, we analyzed key bilateral agreements and official statements, all major arms sales and other forms of military-technical cooperation, exchanges of military personnel for education and training, joint military exercises and operations, and other relevant military-to-military engagements. Our analysis primarily covers the period from 2014 to November 2022. We included earlier cooperation where relevant and also included some important developments between November 2022 and February 2023.

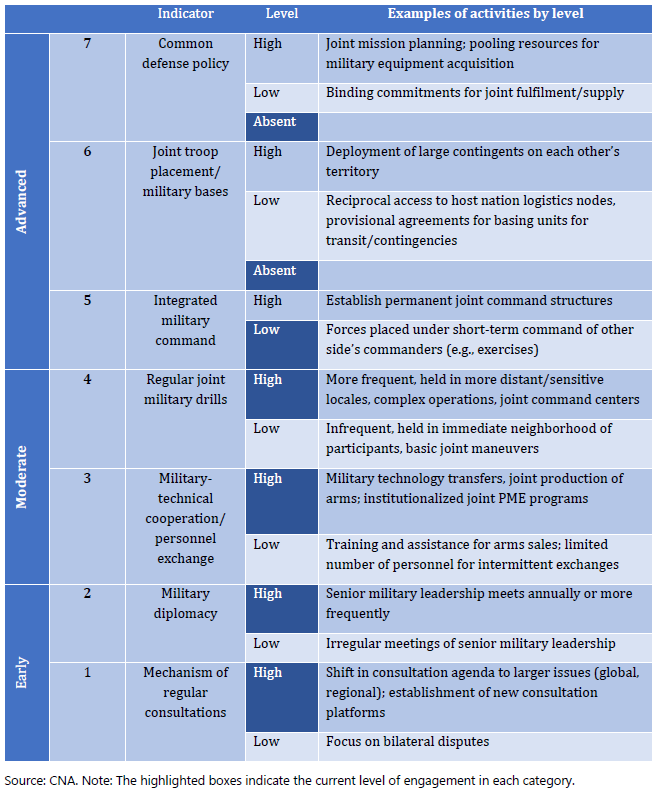

We adapted a scale that assesses levels of military cooperation based on seven issue areas, ranging from the establishment of mechanisms of regular consultation at the low end to the adoption of a common defense policy at the most advanced end. This methodology allowed us to not only estimate the current level of overall military cooperation between Russia and China, but also to analyze its recent course and thereby estimate its potential future trajectory. In addition, by examining components of military cooperation, we can identify specific areas where it is developing faster or slower than the overall average. This examination allows for a more fine-grained analysis of developments in Russian-Chinese military cooperation.

A Record of Uneven Growth

Russian-Chinese military cooperation has not always grown linearly. At various points, some aspects have undergone periods of rapid expansion, while others contracted. At other points, previously growing areas have in turn plateaued. This unevenness in the dynamic of cooperation growth has been most notable in military-technical cooperation and in joint exercises and operations, while the expansion of political consultations and military diplomacy has been more constant. Despite a number of rhetorical flourishes at leadership summits, after undergoing a period of rapid expansion from 2014 to 2019, Russian-Chinese military cooperation has largely plateaued in recent years. There is little evidence of continued expansion since 2020 in either military-technical cooperation or joint military activities.

Over the last two decades, Russia and China have developed well-institutionalized political and military consultation mechanisms. The most important mechanisms include numerous summits between Putin and Xi, annual bilateral security consultations between Nikolai Patrushev, the head of Russia’s National Security Council, and Yang Jiechi, the former head of the Chinese Communist Party’s Foreign Policy Commission, and the semi-annual Northeast Asia security dialogue at the deputy foreign minister level. Since 2017, China and Russia have organized their military cooperation plans in five-year roadmaps, with the most recent such plan agreed to in 2021 and lasting through 2025.

The bilateral security consultation mechanisms were initially designed in 2001 to manage bilateral territorial disputes, which were resolved by 2004. The political-military agenda has since expanded considerably. Prior to 2014, the primary focus remained on developing and expanding bilateral military cooperation, including both arms sales and joint exercises. With relations with the West cratering after the 2014 invasion of Ukraine, Russia sought to expand its relationship with China. The two countries began to coordinate more broadly on security issues, including assessments of threat perceptions of the West, positions on each other’s territorial and geopolitical disputes with third countries, and efforts to expand cooperation on strategic issues, such as the development of joint missile early warning systems.

A joint statement issued following the Putin-Xi February 2022 meeting that took place just before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine demonstrated increased overlap in the two sides’ security concerns. Both countries focused on the threat posed by the United States and NATO to international security in general and to their own countries in particular. Chinese officials have refused to criticize Russia’s invasion, generally blaming NATO and U.S. threats for causing the war.

Military-Technical Cooperation

Russian-Chinese military-technical cooperation has varied over the decades since the end of the Cold War. After a period of extensive growth in Russian arms sales to China from 1991 to 2005, military-technical cooperation was fairly limited during the following decade because of a combination of growing Chinese self-sufficiency and Russian reluctance to share its most advanced technologies based on past Chinese reverse engineering practices. As with several other areas of military cooperation, Russian arms sales to China grew rapidly for a short time after Russia’s 2014 conflict with Ukraine. The expansion was driven in part by Russia’s willingness to break with precedent and sell China more advanced weapons systems. However, this growth has not been sustained in recent years, as China, guided by Xi’s growing emphasis on technological self-reliance, has continued to increase its self-sufficiency.

Even as arms sales have become a less significant aspect of the overall bilateral military cooperation relationship, joint technology projects have rapidly become increasingly important. The two sides have launched a variety of joint military production projects, including a heavy-lift helicopter, a new conventional submarine, enhanced cooperation on tactical missiles, and high-tech projects with potential military applications in spheres such as artificial intelligence and space systems. Most critically, Russian assistance in the development of a Chinese missile launch early warning system highlights the expansion of cooperation to strategic defense.

At the same time, when discussing purely military technology development, the partnership has remained somewhat one-sided, with little evidence of technology transfer from China to Russia. Russia has turned to China in its efforts to replace key Ukrainian and Western dual-use components, especially in areas such as optics and electronics, although these projects have been limited to some extent by sanctions. Some projects initiated after 2014, especially the purchase of Chinese marine engines, have been curtailed because Chinese equipment was found to be of insufficient quality. China has also to date refrained from overt efforts to help Russia avoid Western sanctions following the 2022 invasion of Ukraine.

Nevertheless, the shift from arms sales to joint projects with technology transfers suggests an increase in defense industry integration, with higher levels of mutual dependence and institutional coordination. Overall, Russian-Chinese military-technical cooperation continues to operate at a high level, though there is potential for further growth if the two sides can overcome lingering concerns over issues such as reverse engineering, competition in global arms markets, reluctance to share sensitive technologies, and an enduring preference to maintain self-sufficiency in defense production.

Joint Exercises

Russia and China demonstrate a high level of cooperation in military exercises and joint operations. As with other aspects of their military cooperation, joint military exercises and operations underwent a rapid period of expansion in the mid-2010s, with increases in the frequency and global reach of joint activities and a transition to increasingly complex exercises designed to improve coordination.

Joint exercises have included efforts to integrate the use of each other’s military equipment and facilities, as well as the establishment of temporary joint command centers for the purpose of conducting specific exercises and operations. All of these activities have allowed both sides to increase trust and cooperation at the operational level. At the same time, working together with Russian forces that have experienced battlefield conditions in operations in Syria and Ukraine has helped the Chinese military to improve operationally by learning more advanced tactics and procedures, as part of its effort to compensate for its overall lack of operational experience. The exercise program has also provided symbolic benefits to both sides, allowing both China and Russia to demonstrate that they are working together against U.S. threats and efforts at “world domination.”

As with military-technical cooperation, the frequency and geography of military exercises expanded rapidly in the mid-2010s but has largely plateaued in the last three years. However, the exercises have continued to become more advanced during this period. The launch of joint air and naval patrols in 2019 and 2021, respectively, highlights an effort to move beyond exercises and into real-world operations. These patrols now occur regularly, with the sixth joint air patrol taking place earlier this month, though to date they differ little in practice from military exercises. The decrease in frequency and lack of geographic expansion of exercises since 2020 is primarily the result of constraints introduced first by the COVID-19 pandemic and later by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. While the former no longer affects bilateral military activities, the latter may continue to act as a brake on the availability of Russian military assets for exercises with China.

Limits to Cooperation

Russia and China have demonstrated relatively few aspects of the advanced military cooperation practiced by the United States with its European and Asian allies, which generally occurs through the establishment of integrated military command centers, joint deployments, base sharing, and, at the highest levels, the formulation of a common defense policy. The episodic establishment of joint operation centers for specific exercises and the occasional use of each other’s military facilities remain the only cases of advanced military cooperation. Beyond that, Russia and China have not shown any indication of planning to establish permanently operating joint command structures. Apart from specific exercises, they have also generally not provided each other with access to host-nation logistics nodes, nor have they sought to negotiate agreements for basing military units or equipment on each other’s territory, either permanently or temporarily. Finally, neither side appears interested in discussing the formulation of a common defense policy at any level, even the lowest levels, such as commitments for joint fulfillment and supply. As a result, we assess that China and Russia have not reached an advanced level of defense cooperation, though they have taken some very preliminary initial steps in that direction. The table below summarizes the current state of Russian-Chinese military cooperation.

Implications

Russia and China derive significant advantages from their military cooperation. While the most significant benefits come in the form of mutual political support on the international stage, there are also clear benefits in terms of defense industrial production and improvements in operational capabilities, especially for the Chinese side. There is the political symbolism of Russia and China supporting each other in fighting against what they consider to be U.S. efforts to preserve its global hegemony. To this end, joint statements by senior leaders, such as the February 2022 announcement of a “friendship without limits” by Putin and Xi, highlight that the two countries have similar strategic positions on global issues. Although their March 2023 joint statement more clearly specified that their partnership fell short of a military alliance, the two leaders claimed to have forged a “superior” relationship that would withstand the test of time.

Concrete actions such as arms deals and major joint exercises have a strong symbolic component, showing that the two countries are working together to address global challenges and to strengthen each other’s positions in the world. These symbolic benefits are particularly important for Russia as it seeks to counter the perception that it is isolated internationally as a result of its invasion of Ukraine. After Chinese Defense Minister Li Shangfu met with Putin in April 2023, for example, he hailed the Russian leader’s contribution to world peace. Russia highlights the willingness of Chinese leaders to meet with Russian leaders at the highest levels, and the statements of support that are regularly issued after such meetings, as a sign that Western efforts to isolate it are failing.

On the other hand, there is a clear sense that China gains more from the defense relationship than Russia does in terms of the material benefits of military cooperation. The People’s Liberation Army has long used military exercises to learn from its Russian counterparts and to improve operationally. China could also gain strategically from potential access to Russian military facilities in the Far East, though there is little indication that Russia is willing to grant such access in the foreseeable future. The Russian military, which sees itself as more advanced in operational knowledge than its Chinese counterpart, has gained less in practical terms. At the same time, Russia’s performance over the last year in its war with Ukraine may introduce some doubts among Chinese military leaders about the quality of the Russian military, which may in turn affect the perceived utility of what the People’s Liberation Army may be able to learn from joint exercises and operations. While it is far too early to see evidence of such a shift in Chinese perceptions, it is a possibility that observers should consider going forward.

For many years, China has leaned heavily on Russian weapons exporters to help facilitate its military modernization. This assistance has been particularly critical because for most of the post-Cold War era, its defense industry lagged far behind its Russian counterpart and China was not able to purchase weapons from the West to catch up. Moreover, by assisting China principally in the maritime and aerospace domains, Russia has supplied weapons that pose a comparatively smaller threat to Russia and a comparatively larger threat to the United States. That said, Chinese dependence on Russian arms supplies is clearly waning as its defense industry becomes increasingly self-sufficient. Most of the armaments that China has in the past bought from Russia can now be produced domestically, with aircraft engines being the one major exception. On the other hand, the enactment of comprehensive Western sanctions against Russia in the aftermath of its invasion of Ukraine has increased Russian dependence on Chinese components such as electronics and on Chinese machine tools. For the most part, China has been very careful to avoid providing any equipment to Russia that might violate Western sanctions, although the U.S. Treasury imposed sanctions on a few Chinese companies that provided military aid and U.S. officials caution that the Chinese leadership has not fully rejected the prospect of such assistance in the future.

Although the overall rapid expansion of Russian-Chinese military cooperation in terms of military-technical cooperation and joint exercises that was clearly in evidence in 2014–2019 has not been as evident in the last three years, the continued frequency of security consultations and the issuance of statements reaffirming close military ties during the 2020–2022 period suggests that this lull is most likely the product of external circumstances rather than a change in the willingness of either party to continue to pursue the development of an ever-closer military relationship. If this is the case, then it is these circumstances — including Western sanctions and resource constraints faced by the Russian military as a result of its invasion of Ukraine — that will determine whether there is a renewed push to further expand the military relationship in the coming years.

In determining the trajectory of the relationship over the next three to five years, analysts should focus on the extent to which China is supplying Russia with military and dual-use technologies and how much real assistance Russia is providing to China through joint projects such as the early warning system and advanced heavy-lift helicopters. In the joint exercises and operations sphere, observers should examine whether or not China and Russia are conducting military exercises that are provocative to third-party states, such as in the Greenland, Iceland, United Kingdom (GIUK) gap or near U.S. territory in the Pacific, or if either undertakes missions that are primarily of importance to the other, such as joint naval activities in disputed areas of the South China Sea, near Taiwan, or in the Mediterranean or Baltic Seas. In addition, any indication that either side is willing to grant the other long-term access to its military facilities would be a sign of an appreciable advance in military cooperation and mutual trust. These actions would indicate that the two countries are potentially on the path to a deeper level of military cooperation that might create serious threats to U.S. allies and partners and greatly increase the challenge facing U.S. military planners. Evidence that Russia and China are engaging in this type of cooperation will be more significant than further ritual statements about unlimited friendship made at summit meetings.

Dmitry Gorenburg is a senior research scientist in the Strategic Studies division of CNA, a not-for-profit research and analysis organization, where he has worked since 2000. He is the editor of the journals Problems of Post-Communism and Russian Politics and Law and an associate at Harvard University’s Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies.

Elizabeth Wishnick is an expert on Sino-Russian relations, Chinese foreign policy, and Arctic strategy in the China Studies Program at CNA. She is also a senior research scholar at Columbia’s Weatherhead East Asian Institute and a professor at Montclair State University. She is the author of China’s Risk: Oil, Water, Food and Regional Security (forthcoming) and Mending Fences: Moscow’s China Policy from Brezhnev to Yeltsin. Her policy blog is at www.chinasresourcerisks.com.

Paul Schwartz is a research scientist in CNA’s Russia Studies Program, and conducts research and analysis on Russia’s military and its defense and security policy for the U.S. military and the intelligence community. He is also a non-resident senior associate in the Europe, Russia, and Eurasia Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Brian Waidelich is a research scientist in the Indo-Pacific Security Affairs Program at CNA. His research focuses on Chinese People’s Liberation Army organization and Indo-Pacific maritime and space security issues.

Image: The Kremlin