Don’t Count on Us: Canada’s Military Unreadiness

Canada’s military is in a “death spiral.” This is how Minister of National Defense Bill Blair described the state of Canada’s armed forces at last month’s Ottawa Conference on Security and Defense. Blair’s comments referenced the military’s dire recruitment and retention crisis. The Canadian Armed Forces are short 16,000 people — about 15 percent of their authorized strength of 71,500 regular forces and 30,000 primary reserve forces. Despite efforts such as opening the military to permanent residents, there’s no indication that the situation will improve. Less than 1 percent of applications from permanent residents to join the regular force were accepted, with 15,000 applicants walking away amid the 18- to 24-month-long application process. While the Canadian government has signed several high-profile contractsfor new equipment such as F-35s, Predator drones, and P-8A Poseidons, at this rate, there may not be anybody to use these capabilities when they come online.

Allies and critics are rightfully calling on Canada to meet the 2 percent of gross domestic product spending target agreed to by NATO, but the Canadian military’s troubles are deeper than insufficient funds. Canada’s ability to meaningfully contribute to major allied operations is in doubt for the foreseeable future. Despite increased defense spending by 70percent between 2017 and 2026, an internal report on the readiness of the Canadian Armed Forces was released to the media the same week that Blair made his remarks. The report paints a bleak picture: Most of Canada’s major fleets are unavailable or unserviceable. Indeed, on average, only 45 percent of Canada’s air force fleet is operational, while the Royal Canadian Navy can operate at 46 percent of its capacity and the army at 54 percent. This means that even Canada’s minor military projection ambition — which consists of only three frigates, two fighter jet squadrons, and one mechanized brigade — is not assured. As the ninth largest economy in the world and twelfth largest per capita, Canada actually contributes little to allied security and cannot be relied upon to sustain its own limited ambition.

There are few indications that things will get better soon. On 8 April 2024, the Canadian government announced more than $72 billion in new defense funding over the next two decades. This is projected to bring Canadian military expenditures to a peak of 1.76 percent of gross domestic product in 2029. This is a welcome injection of funds on top of the nearly $215 billion the Canadian government is expecting to invest in the armed forces over the next 20 years. Most of this new spending, however, is years away and won’t address the military’s immediate woes. To be blunt, Canada’s military is in an atrocious state and is barely holding on. The roots of this crisis are found in Canada’s strategic culture and decades-old decisions about defense. The way out of the crisis, meanwhile, is paved with seemingly insuperable obstacles, including a chronic shortage of personnel, an inability to spend funds quickly, a lack of bipartisan agreement on military requirements, and a culture of reactiveness and unpreparedness toward new geopolitical challenges.

Even if vital reforms and budget increases were made today, they would take years to implement and at least a decade to rehabilitate the armed forces. For Canada, this is all the more reason to start as quickly as possible. For Canada’s allies, it is further reason to have realistic expectations about Canada’s military contribution over the coming years. In short, don’t count on Canada until structural reforms are implemented.

Canada and National Defense

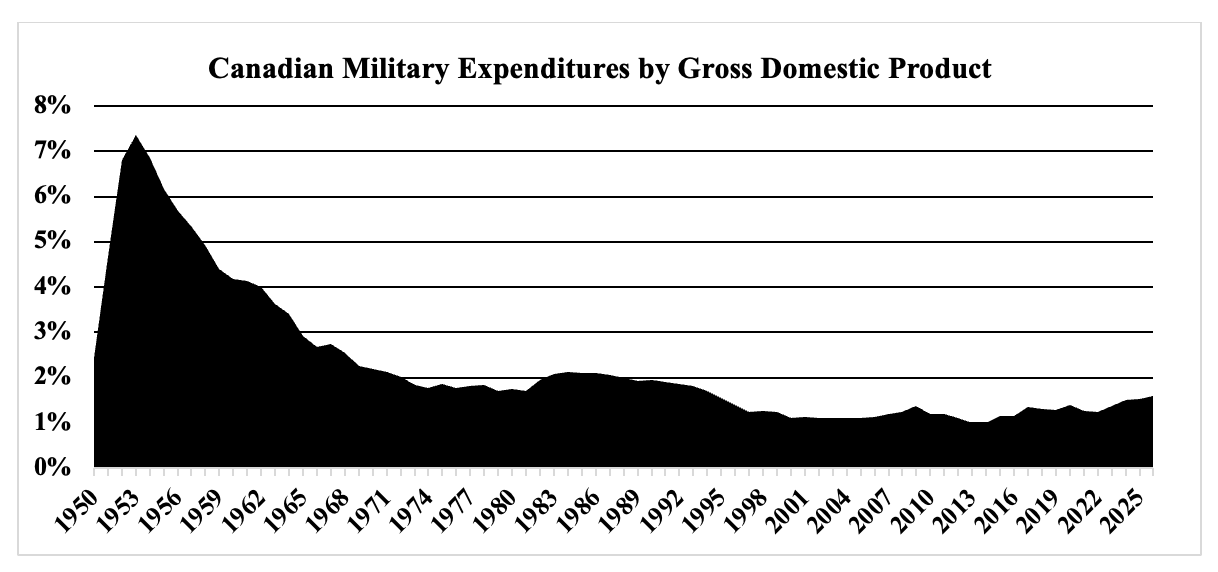

To understand Canada’s current military crisis, it is important to recognize how little importance Canadians ascribe to defense. Although recent polls indicate that attitudes are changing, particularly among conservative-leaning voters, Canadians have rarely seen defense as a priority. Surrounded by three oceans and neighboring the world’s largest military power, Canadians have rarely thought that defense spending was a worthwhile investment, particularly when compared with popular social programs. There have been exceptions, of course. Canada contributed heavily to both world wars. The Korean War prompted Canada to invest heavily in its military and to forward-deploy forces to western Europe during the early Cold War. Once an adversary was defeated or the threat appeared to cool down, however, Canadians have allowed defense spending to stall and its military capabilities to decline. Notably, after the initial surge in spending that followed the Korean War, Canadian defense spending began a slow but steady decline starting in the late 1950s. The Canadian military underwent a major recapitalization in the mid-1970s, but it never again matched the peacetime capacity that it briefly enjoyed in the early Cold War.

Both Canadian leaders and the voting public have been happy to coast on the military reputation that the country earned more than 70 years ago. Like an out-of-shape former high school star athlete who clings to their glory days, Canadians still imagine themselves as they were back then, not as they are now, although a growing number think their country’s reputation has worsened lately. Worse still, Canadians and their leaders believe that their allies see them how they see themselves. The result has been a mix of smugness and complacency that has prevented Canada from confronting the true extent of its military decline.

Faced with today’s worsening international security environment, Canadians are again realizing that they should step up militarily. But the decades-long neglect of their armed forces will make it far harder for Canada to make meaningful contributions to international peace and security in the coming years. Although the roots of this crisis date back the Cold War, the Canadian Armed Forces’ current situation is best understood with references to the decades that followed it.

The Peace Dividend

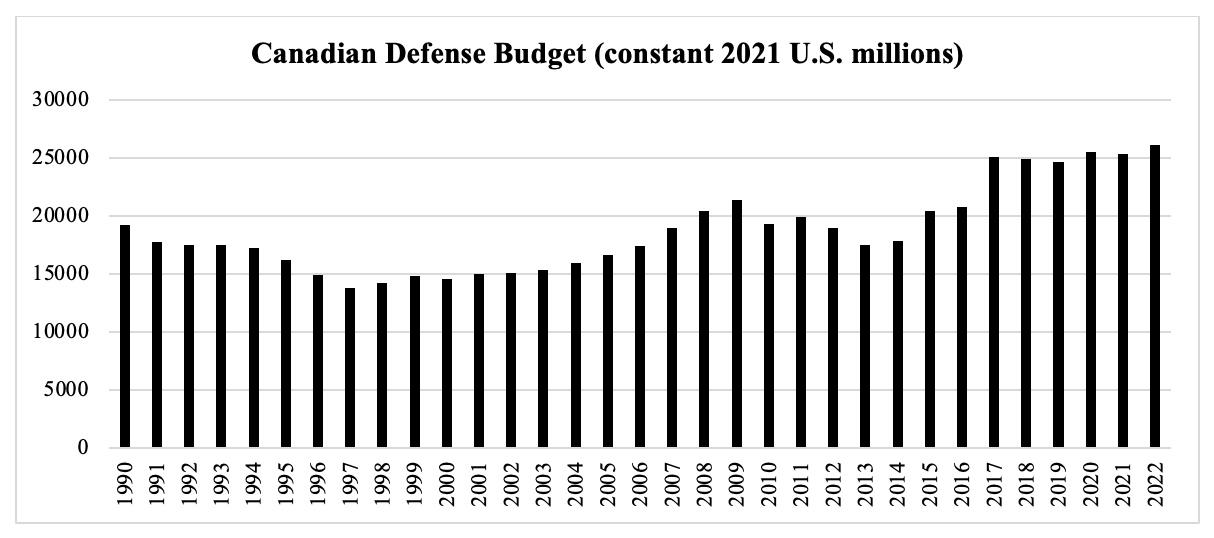

When the Cold War ended, Canadian governments eagerly sought a peace dividend. Canada’s finances were an utter mess at the time, and the defense budget was an easy source of discretionary spending that could be cut. In the mid-1990s, the Canadian defense budget was slashed by 30 percent. But the downward trend had already begun, with defense expenditures as a percentage of gross domestic product steadily declining from 2.11 percent in 1986 to 1.11 percent in 2005. The government reduced the size of the force by one-third, from 90,000 active troops in 1990 to 62,000 in 2005. Ottawa held back on major recapitalizations during this period, ensuring that there would eventually be a bow wave of projects in need of dire attention. In many ways, the Canadian military is still living with the effects of this era, in terms of not only the talent who exited, but also the stress placed on infrastructure, equipment, and people.

In spite of these cuts, the government committed the Canadian Armed Forces to a high operational tempo, deploying the military in the Gulf War, Somalia, Bosnia, Haiti, Kosovo, Afghanistan, Libya, and Iraq. On average, Canada contributed over 4,300 troops annually to military operations abroad during the 1990s. This contrasts with a respective average of 3,400 in the 2000s and 1,600 in the 2010s. Dramatic cuts in the size of the force and its capabilities, as well as a shift from taking part in United Nations peace operations to NATO and U.S.-led offensive operations, explain this trend downward.

Recapitalization Plans Falling Short

After 9/11, Canadian defense spending slowly crept up, particularly after the military was deployed to Kandahar, Afghanistan. Not only did this mission remind Canadians of the dangers associated with an under-equipped military, but also the “Global War on Terror” led to greater interest in military service. Military expenditures grew from 1.11 percent of gross domestic product in 2004 to 1.38 percent in 2009. In constant U.S. dollars, expenditures in this period underwent a growth of 34 percent. Successive governments began to approve new capabilities as well. Starting in the mid-2000s, Canada acquired C-17 strategic airlift planes, C-130J tactical lift aircraft, and Chinook medium-lift helicopters. The authorized size of the regular force grew by 13 percent, from 62,000 in 2005 to 70,000 in 2008. It grew slightly more to 71,500 in 2017 and has remained the same in Canada’s 2024 defense update. Therefore, the size of Canada’s authorized force has remained about the same despite the seismic changes of the threat environment since the 2000s.

Toward the end of the 2000s, a defense malaise set in. The war in Afghanistan had inflicted relatively heavy casualties on a force and country that had not suffered major losses since the Korean War. Canada suffered the third largest share of casualties per capita (following Denmark and Estonia) during the war in Afghanistan (158 soldiers and 7 civilians). Political opposition to the war was also notable, pushing the government to look for an exit strategy. In 2011, Canada was the second ally after the Netherlands to withdraw from Afghanistan before the end of NATO’s combat mission in 2014. This is significant given that Canada has taken part in every NATO operation since its creation.

Capital projects faced mounting costs, leading to the cancellation of a much-vaunted joint support ship. In an effort to rebuild the Canadian shipbuilding industry following this cancellation, a national shipbuilding strategy estimated at $33 billion was put in place. The strategy has since begun to deliver four Arctic offshore patrol vessels (two more are expected this year), but the construction of 15 Canadian surface combatants, based on the Type 26 hull and intended to replace Canada’s fleet of 12 frigates and four destroyers, has yet to begin. Estimated at $26 billion in 2015, the acquisition of Canada’s main combat ships is now expected to cost more than $80 billion, which makes some question its affordability. As worrisome, the delivery of the first ship is expected in 2032 and the last in 2050, about six decades after Canada commissioned its frigates between 1992 and 1995.

A fleet of 15 ships is considered by many as the minimum required to meet the Canadian government’s commitments, which include deploying three ships in the Indo-Pacific region on an annual basis, as well as partaking in NATO’s standing maritime groups on a rotational basis. For the first time since Russia’s annexation of Crimea and amid its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Canada was unable in 2022 to take part in NATO’s maritime task forces because of insufficient serviceable ships to undertake both NATO and Indo-Pacific commitments. Yet the Canadian government committed in 2019 an extra high-readiness frigate to NATO, for a total of three, as part of the latter’s readiness initiative to have 30 naval combat vessels ready to use in 30 days (in addition to 30 battalions and 30 air squadrons). This was before NATO’s decision in June 2022 to boost its rapid reaction force from 40,000 troops to over 300,000. Given the slow procurement pace and absence of any sense of urgency in the face of its obsolescent fleet, Canada will continue failing to meet its already small target of having three frigates available for operations at any point in time, to say nothing of actually increasing its ambition level to a consequential force.

The situation is not better with regard to Canada’s air force. When the government attempted to acquire 65 F-35 combat jets in 2010, critical reports from the office of the auditor general and parliamentary budget officer pushed the government to reset the process. Twelve years later, the F-35 won a competition that was eventually held, but the first delivery is expected in 2026 and the new fleet will only achieve full operational capability in 2034. This will be more than 50 years after Canada introduced its first CF-18 Hornet to its fighter aircraft fleet. It is unclear how many will remain serviceable by this time.

In 2016, the Canadian government announced it would explore buying 18 new Super Hornet fighter aircraft to close a newly found “capability gap” in Canada’s air force fleet. The government increased the fleet’s operational requirements to sustain the highest North American Aerospace Defense Command alert level — which is about 36 aircraft, with 12 operational aircraft — simultaneously to a squadron of six fighter jets to NATO operations in Europe. After a trade dispute with Boeing, the Canadian government pulled out in 2017 from the purchase of Super Hornets. It did, however, maintain its higher operational requirements by vowing to purchase 88 fighters (instead of the 65 originally planned). However, Canada then doubled to 12 combat aircraft its commitment to NATO as part of the latter’s 2019 readiness plan. It remains doubtful whether the new fleet size will be able to meet both North American Aerospace Defense Command and NATO commitments simultaneously in the face of the new threat environment. In the meantime, Canada’s lack of air crews will jeopardize its capacity to sustain its small Defense Command commitment while training crews for a new fleet of F-35s.

The new fighter competition was part of a recapitalization the Canadian Armed Forces launched in 2017. Under the Strong, Secure, Engaged defense policy announced that year, the government outlined a capital program totaling more than $160 billion over 20 years. In 2022, the government further committed another $40 billion to modernize the North American Aerospace Defense Command alongside the United States. All told, the expected capital expenditure for defense until 2037 is expected to reach $215 billion. This rapid and substantial acceleration in capital spending has raised concern from the parliamentary budget officer, who questions Canada’s ability to manage such an increased procurement activity. Furthermore, due to procurement delays, 62 percent of the planned expenditures are now expected to occur after 2027. Given the high inflation rates in the defense industry, additional appropriations will probably be necessary to maintain the current planned acquisitions. In other words, Canada’s current defense policy is fiscally unsustainable.

This recapitalization plan has led to contracts for new capabilities. Over the past two years, Canada has contracted to acquire new air-to-air refueling and VIP transport aircraft, a fleet of P-8s, light trucks, Predator drones, and a suite of land command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance systems. Still more procurements are on the way and will continue to be made into the 2030s. The government’s April 2024 defense policy update, for instance, is committing tens of billions of additional dollars for new tactical helicopters, defense infrastructure, long-range missiles, artillery ammunition, satellites, airborne early-warning aircraft, and a cyber command, among other things. Since all these initiatives are on top on what has already been announced since 2017, these new announcements are good news, but remain decades away.

In the meantime, however, the age of the Canadian military’s existing equipment is having a predictable effect on serviceability. Older fleets require more maintenance and repair. Parts for older and smaller fleets are difficult to secure. Indeed, the 2024 defense policy update sets out $9.9 billion to keep Canada’s existing warships afloat and supplied and another $8.9 billion to sustain its military equipment. The ongoing recapitalization will alleviate this challenge over the coming decade, but the Canadian Armed Forces’ readiness will be hobbled for many years because of procurement decisions that were put off for too long.

While the capital side of things has a glimmer of hope, a sense of despair surrounds the wider Canadian military. The regular force has been short of personnel for years. Military bases and housing have been allowed to fall into significant disrepair, and personnel policies have not kept pace with the expectations and demands of contemporary work and family life. A strong economy has meant that military members were offered attractive opportunities in the civilian world, without the sacrifices the military imposed on them. When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, the Canadian Armed Forces were already in a fragile state. Increased domestic deployments during COVID-19 and the tight labor market that followed made the situation worse. Truth be told, many militaries are short of personnel and having difficulty recruiting since the pandemic. But the Canadian military appears to be faring particularly poorly. Indeed, a lack of technicians across the force has likely exacerbated the serviceability challenges facing its major fleets.

Still another challenge has been the sexual misconduct crisis surrounding the Canadian military in recent years. Several military leaders were either charged or forced to resign in light of sexual misconduct allegations made against them. Given the number of cases, fixing the Canadian Armed Forces’ culture with respect to sexual misconduct has been the current government’s top military priority. The sexual misconduct crisis has made the Canadian military’s recruitment and retention challenges worse. A cloud has been hanging over the institution for several years now, which has led younger Canadians to question whether they should join and perhaps compelling serving members to look elsewhere.

“Exploring Options”

As part of its 2024 defense policy update, the Canadian government outlined several capabilities that it plans to “explore,” meaning that most are not even at the options analysis phase and have yet to be budgeted. These include new submarines, main battle tanks, light armored vehicles, surveillance and strike drones, and artillery. As well, the policy mandates the defense department to explore counter-drone capabilities and long-range air- and sea-launched missiles.

While all these capabilities are essential in the current threat environment, the case of the submarines is particularly glaring. Given that the cost of replacing Canada’s four aging diesel-electric submarines has been pegged at somewhere between $60–$100 billion, the government’s decision to merely “explore” options isn’t all that surprising. As noted, the new policy already includes more than $70 billion in new spending over 20 years; an additional $60–$100 billion was clearly deemed too much. Given that the ongoing modernization of Canada’s Victoria-class submarines is expected to keep them operational until the mid-2030s, the lack of funding for a replacement option in a policy update looking into the mid-2040s may result in Canada losing this capability. This capability gap will occur despite the government recognizing the need for submarines to “detect and deter maritime threats, control our maritime approaches, and project power and striking capability further from our shores, at a time when Russian submarines are probing widely across the Atlantic, Arctic and Pacific Oceans and China is rapidly expanding its underwater fleet.”

On the personnel front, the new defense policy presents a few ideas, but none that promise to rapidly reverse the Canadian Armed Forces’ dwindling numbers. Ottawa is still examining options and has yet to budget for greater compensations and benefits for personnel and work-life balance for the troops. Of note, the policy outlines a probationary period for new recruits to get them in uniform sooner, along with more career control for those already serving. Just as important, the new policy pledges to expand the civilian defense workforce, with a view toward augmenting the department’s capacity to support the armed forces and handle the ever-present procurement and infrastructure projects. Coupled with the shortfall in military personnel, the civilian defense workforce has been stretched to the limit as it has tried to implement the recapitalization of the Canadian Armed Forces. Until the civilian side of the equation can handle more programs, the defense department and armed forces will continue to have trouble spending the additional money they’ve been allocated.

Conclusion

Where does this leave the Canadian military today? Its existing fleets are increasingly difficult to service and maintain, either owing to a lack of personnel or as a function of their age. Canada has had to scale back its participation in major military exercises, and its contributions to allied operations are consistently anemic. A lack of personnel and fleet serviceability is constraining the number and size of the operations that the military can undertake. In 2023, the Canadian Armed Forces conducted a record of 141 days in operations supporting civilian authorities against natural disasters. The increasing frequency and intensity of domestic needs due to climate change are challenging for the Canadian military’s limited capacity. Internationally, only 58 percent of Canada’s committed “force elements ready to meet NATO notice move” are deployable. This means that Canada’s 3,400 troops supposedly on a higher state of readiness may not be able to support the 1,200 currently deployed in Latvia to help deter and defend against Russian aggression. Yet as a framework nation for NATO’s enhanced forward presence in Latvia, Canada is expected to boost NATO’s battle group to brigade level by doubling its deployed force in the Baltic country. Canada’s capacity to sustain this commitment is uncertain given its chronic readiness problems. Despite pleas from Washington, moreover, Canada has refused to lead a mission to Haiti — not only because Ottawa does not want to accept the risks involved, but also because the military is in no position to mount a significant intervention. Canada is instead merely supplying 70 troops to train Jamaican troops for a mission to Haiti. This will continue to expose the country to fierce critiques from Washington, and most notably Trump-aligned Republicans, while further undermining Canada’s reliability toward its European allies.

Unless the Canadian Armed Forces solve their personnel crisis, they may not be able to operate the new equipment that is being procured. As pressure on serving personnel increases due to shortfalls within the ranks, more members will be inclined to leave. This is the death spiral the defense minister warned about. While money is not a panacea, spending 2 percent of gross domestic product in defense could help address the shortage of personnel and crumbling infrastructure, as well as acquiring the missing capabilities to sustain operations in the current threat environment. But Canada first needs to solve its structural defense planning issues and, as important, its complacent and self-righteous attitude regarding a military reputation it let slip long ago.

Philippe Lagassé is associate professor and the Barton chair at the Norman Paterson School of International Affairs, Carleton University.

Justin Massie is full professor and head of the department of political science at the Université du Québec à Montréal and codirector of the Network for Strategic Analysis.

Image: Petty Officer 2nd Class Robert Simpson