Fearing Their Officers More Than the Enemy: Summary Executions from George Washington to Ukraine

On the most recent episode of The Russia Contingency podcast, Michael Kofman and Rob Lee discussed a variety of structural factors impacting Ukraine’s ability to fight, from drones to manpower, ammunition to motivation. As an 18th-century military historian, I focused on the executions. Referring to his recent trip to the frontlines, Lee explained:

Russia is able to form a large number of infantry units, and those units are going into combat. They’re doing assaults, they’re not just turning away. One of the big questions I had … was, “How are they doing this? How are they motivating units to go into assaults?” Obviously many of them fail completely, and they take heavy losses, but one notable thing that we were told on this trip is that the Russian military is increasingly using execution as a means of maintain morale and discipline … the threat of execution and also execution itself. It is well known that Wagner was using executing prisoners last year as a key way of forcing prisoners to conduct assaults, it looks like the Russian military is doing that too. And this wasn’t just from one source, we were told this from different brigade commanders on several parts of the front, it was a pretty consistent theme. … What we were told was, at least in some cases, was that squad leaders were empowered to conduct executions.

This technique of course, is nothing new. 18th-century commanders, when things weren’t going their way, frequently encouraged their officers to use threats of violence, as well as violence itself, in order to steady the men. As I’ve argued before, we need to understand the seemingly foreign, backward, and brutal actions of the Russian military by using the past, in order to better “think outside the parameters of the present.”

The idea of squad leaders gunning down their own men is deeply revolting to the Western military establishment. The standard narrative of Western military history runs that, from the American Revolution and French Revolution down to the present, the citizen-soldiers produced by the West have been led forward by a positive inner leadership and the inspirations of their officers. This sentiment would have seemed odd to George Gordon Meade, famous for his command of Union forces at Gettysburg during the American Civil War. At Antietam, Union soldier Frank Holsinger recalled that Meade saw a man break ranks to flee, and non-commissioned officers unwilling to deal with him.

General Meade rushes up with, ‘I’ll move him!’ Whipping out his saber, he deals the man a blow, he falls — who he was, I do not know. The general has no time to tarry or make inquires. A lesson to those witnessing the scene … I felt at the time the action was cruel and needless on the part of the general. I changed my mind when I became an officer, when with sword and pistol drawn to enforce discipline by keeping my men in place when going into conflict.

Here, Meade was drawing on a tradition in the American military: Far from being an outlier, calling for the execution of shirkers went back to the founding father of the American army, George Washington. In charting this story, I show that there are parallels between the foreignness of the Russian military today, and the foreignness of the American military in the past. In making Russian actions more intelligible, I still find them horrifying. Thankfully, threats of death and summary executions have ceased to be a part of the American military tradition, but there was a time when they were more common. And they may work for Russia better than we would prefer to think.

The Continental Army and Summary Executions

Across military Europe during the 18th century, officers believed that they had the “right and duty to kill any soldier who ran away, or even looked as if he might turn tail.” Long influenced by statements from Frederick the Great’s political testament of 1768, anglophone historians have used concepts like this to argue that soldiers in military Europe had a radically different code of honor than the private soldier under Washington. Charles Royster, in his magisterial A Revolutionary People at War, falls into this trap. In an otherwise excellent study of the Continental army, Royster asserts:

Frederick the Great said that soldiers should fear their officers more than the enemy, but the Continental Army never achieved this level of systematic intimidation, even though Washington’s general orders before battle sometimes backed up appeals to patriotism with warnings that those who ran would be shot on the spot. Unlike Frederick, the revolutionaries did not allow that fear was relative.

But despite Royster’s dismissal, the use of intimidation by Continental Army officers went far beyond rare references in Washington’s general orders. In his pension application after the war, Benjamin Jones of David Waterbury’s provisional Connecticut Regiment described skirmishing around New York in July of 1781. In a fight involving a Continental scouting party commanded by an Ensign Smith (likely Josiah Smith), Jones recalled coming under attack by a larger party of enemy cavalry. Taking up defensive positions, Smith told his men, frankly, “the first that gave back he would cut off his head with his sword.” With this consequence clearly in their minds, Smith’s men stood firm, and drove off the enemy cavalry with substantial losses. Smith used tactical acumen combined with a healthy respect borne of intimidation to inflict an unlikely defeat on a superior enemy.

At the Battle of Assunpink Creek, Capt. Thomas Rodney commanded a column of infantry approaching the enemy. Rodney recalled:

The fire was very heavy and the light troops were ordered to fly to the support … as we drew near I stepped out of the front to order my men to close up; at this time Martinas Sipple was about 10 steps behind the next man in front of him; I at once drew my sword and threatened to cut his head off if he did not keep close, he then sprang forward and I returned to the front.

Though Rodney admits that Sipple later fled the field, he also indicates that this moment was an important step in his development into “a brave and faithful soldier.” Rodney’s comment regarding Sipple’s development was one way in which he mentally justified his harsh action to the reader. Descriptions of Continental officers carrying out field executions of their soldiers are rare, but they do exist. In the lead-up to the Battle of Stony Point in July of 1779, a Continental soldier was executed because of a failure to follow orders that jeopardized the safety of the men in his platoon. William Heath recalled:

As they approached the works, a soldier insisted on loading his piece all was now a profound silence — the officer commanding the platoon ordered him to keep on; the soldier observed that he did not understand attacking with his piece unloaded; he was ordered not to stop, at his peril; he still persisted, and the officer instantly dispatched him. A circumstance like this shocks the feelings; but it must be considered how fatal the consequence would have been, if one single gun had been fired; scores would have lost their lives, and most probably defeat.

These examples provide a small window into the reality of intimidation in the Continental Army. The low number of examples allows historians to draw different conclusions. It is possible that instances of men being killed by their officers were unpalatable for post-war accounts, but it is also likely that this type of battlefield threat or execution was rare.

Washington’s Orders

Washington, for his part, frequently reminded his officers that they could and should kill soldiers who fled from combat. These affirmations were given as general orders, meaning that the men were almost certainly aware of them. Thus, despite being a rare occurrence, it is likely that the threat of death by officers did encourage the men to remain in their platoons.

Washington’s reminders came frequently throughout the war. In 1776, 1777, and 1779, Washington reminded his officers of their ability to conduct summary executions on the battlefield in various general orders before critical operations. Early in the conflict, these reminders specifically referenced soldiers who fled, or were preparing to flee from combat, but by 1779, Washington had expanded this purview to officers who found men leaving their platoons on the march.

Washington’s orders could become more strident in the face of battlefield defeat. Perhaps understandably, then, the clearest expression of these orders came in the wake of the defeat at Brandywine on Sept. 11, 1777. Four days after the battle, Washington gave general orders that in part read:

The Brigadiers and Officers commanding regiments are also to post some good officers in the rear, to keep the men in order, and if in time of action, any man, who is not wounded, whether he has arms or not, turns his back upon the enemy and attempts to run away, or retreats before orders are given for it, those officers are to instantly to put him to death. The man does not deserve to live who basely flies, breaks his solemn engagements, and betrays his country.

Using variations of language, Washington issued similar commands at many points throughout the war, at least before 1780. To avoid summary execution, it would have been best for Continental soldiers not to “skulk,” “hide,” “lay down … without orders,” “retreat,” “quit their posts without orders,” and “turn [their] back and flee.” As the war continued and the Continentals gained proficiency, Washington began to issue more specific orders allowing summary execution — for taking muskets from the shoulder and firing without orders at Stony Point in July of 1779 — and seemed to approve the same for troops leaving platoons on the march in August of 1779.

Although advocating the summary execution of fleeing soldiers may seem odd in the 21st century, contemporaries did not criticize Washington. Civilians, far from decrying Washington’s orders as barbarous, offered encouragement. John Adams wrote to Henry Knox in September of 1776, playfully arguing that the Continental Army needed to adopt the “good old Roman fashion of decimation,” to focus the minds of the soldiery on their tasks. Subordinate commanders also found Washington’s methods acceptable. At the Battle of Guilford Courthouse in March of 1781, Brig. Gen. Edward Stevens placed a few riflemen behind his line of Virginia militia, with orders to shoot down any troops who prematurely withdrew. Although it would be wrong to assume that this was the only reason why, the Virginia militia fought for an admirably long time against the British advance at Guilford.

In the individual sources which describe the incidences threat of summary execution, it is usually linked to a positive outcome: Smith’s men held firm, Sipple became a faithful soldier, the Virginia militia fought tenaciously at Guilford. Indeed, Washington’s repeated calls to execute cowards did not leave a negative impression in the minds of his men. Thus, in the 18th century, soldiers viewed this as a quasi-normal part of warfare, designed to keep them in the fight. Accounts of men actually being killed by their officers are quite rare, although physical punishment for shirkers (being hit with the flat of the sword) was more common. Often, as I argue in my forthcoming book, this type of threat was less effective than positive leadership on the 18th-century battlefield.

Summary Execution and Its Future

Let us stop the history lesson and return to the present so I can offer a few caveats and conclusions. First, I am not making excuses for the Russian military or their behavior on the battlefield, and I am not arguing for the adoption of blocking detachments and summary executions by squad leaders. Like most people in the United States, I support Ukraine and its fight against Russian aggression. If the fight isn’t going your way, threatening to execute your men won’t help. Blocking detachments and summary executions are an example of the way the Russian military is behind the times. But that doesn’t mean that blocking detachments and summary executions won’t help Russia gain ground.

Second, I am not attempting to say that Washington was a brutal or poor commander. His practices were in line with contemporary European ideas from the paradigm army of that time (the Prussian army). I actually think Washington was a competent commander who achieved American independence — certainly, with a lot of foreign help — by creating a professional army of his time, like other states in military Europe. He also set vital political precedents for the United States that endure down to the present.

Third, just because the Continental Army employed blocking detachments and threatened soldiers with summary execution doesn’t make the cause they were fighting for any less noble. Indeed, in the larger chapter of my forthcoming book that this piece is drawn from, I argue that Washington’s appeals to the glorious cause of the Revolution and positive inspiration by officers were just as important as threats of death in American success. Riflemen were used in blocking detachments — they also defeated the British and created a state of affairs where the United States could establish freedom for its citizens and promote self-government around the world.

So what does this mean for Ukraine today? It can be easy to fall into the trap of essentialist thinking on the Russian military: “Russians are brutal, they always have been.” Instead, as we evaluate the horrifying decision to give squad leaders the power of summary execution, we should keep in mind that that a tactic that seems foreign to us today once made sense to military leaders who helped create the modern world. In large-scale combat operations, conducted by quickly mobilized troops on both sides, the fight is more desperate, closer to home, and with higher casualties than anything the United States has seen since the American Civil War and World War II. It is easy to criticize both Ukrainian and Russian decision-making from the safety of North America. I hope that Washington’s experiences and decisions shows what respected American commanders resorted to in desperate circumstances.

Alexander S. Burns is an assistant professor of history at the Franciscan University of Steubenville, studying George Washington’s army and its connections to European militaries. His edited volume, The Changing Face of Old Regime Warfare: Essays in Honour of Christopher Duffy, was published in 2022. You can follow him @KKriegeBlog.

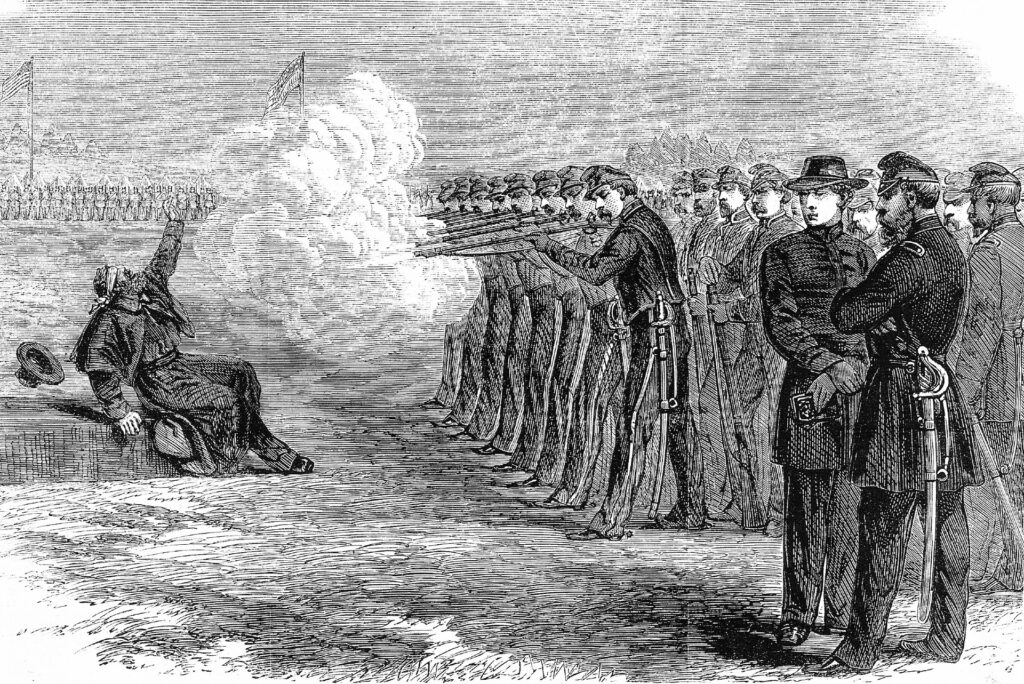

Image: The execution of a deserter in the Federal Camp, Alexandria, during the Civil War in America. Wood engraving. Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark. Source: Wellcome Collection.