Rosalynn Carter: The First Lady and Foreign Policy

Rosalynn Carter’s passing witnessed an outpouring of tributes to an activist first lady who broke boundaries in the realm of foreign policy. Traditionally, the key role of the president’s wife was to act as White House hostess, though there was nothing wrong with her pursuing her own agenda as long as those initiatives did not cross into the realm of policymaking.

Mrs. Carter crossed that line. In addition to serving as one of President Jimmy Carter’s key advisers, she became the first first lady to represent her husband to discuss substantive diplomatic matters with foreign leaders and the first whose presence at cabinet meetings became public knowledge. While the Carters viewed her role as nothing more than a continuation of their partnership, her boundary breaking raised controversy at the time over what the proper role of a first lady should be.

Boundary Breaker

It is important to bear in mind that the concept of an activist first lady was not new. Even before her husband’s tenure as governor of New York, Eleanor Roosevelt in the mid-1920s raised eyebrows by involving herself in state politics. After becoming first lady of the United States, she pursued her own agenda, which included calling for housing for low-income families and protecting the rights of African Americans. Jackie Kennedy became known as an advocate for the arts, Lady Bird Johnson for the environment, and Betty Ford for both ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment and efforts to combat breast cancer.

Furthermore, the concept of an activist first lady was not necessarily considered a bad thing. To the majority of Americans, her primary function was to serve as White House hostess, but there was nothing wrong with her promoting various “gender appropriate” initiatives. The limit was clearly set at making policy. That could mean walking a fine line. Mrs. Ford, for instance, had to be careful that her endorsement of the Equal Rights Amendment did not lead her too far astray from what public opinion regarded as her “proper,” traditional role of hostess and cost her husband political support.

Mrs. Carter had no intention of being hemmed in by custom. If anything, her background reflected a highly intelligent, capable, and determined individual. At age 13, she lost her father to cancer. Consequently, as the eldest of her mother’s four children, she became in many respects co-head of the household, working to help her mother pay bills and making decisions for her siblings. She married Jimmy Carter in 1946; as his work with the U.S. Navy often required him to be away for long stretches, she frequently was alone when raising their three sons. (She did not have their daughter, Amy, until 1967.) After Jimmy quit the Navy in 1953 and the family moved to the Carters’ hometown of Plains, Georgia, Rosalynn helped him run their peanut warehouse business. In 1970, Jimmy won Georgia’s gubernatorial election. As the state’s first lady, Mrs. Carter involved herself in a wide array of initiatives, including assisting those with mental disabilities, convincing Georgia lawmakers to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment, and eliminating corruption in the state’s legal system.

Role in Foreign Policy

As first lady of the United States, Mrs. Carter continued to pursue an array of domestic initiatives, but she also involved herself in foreign policy. Those who have written on the office of the First Lady sometimes use the term “pillow talk” to describe the relationships between presidents and their wives: they, like all spouses, naturally discussed the events taking place in their lives. In the case of the president and first lady, these might include policy matters. President Carter certainly valued his wife’s opinion, and she became one of the most — if not the most — trusted adviser in her husband’s administration. She assisted him with his speeches. The two of them held a weekly luncheon to discuss a broad array of topics, including policy and personnel. In fact, the president once commented that with the exception of a few top-secret national security issues, his wife knew all that was going on in the White House.

The first lady, however, broke an unwritten rule in 1977. Presidents’ wives had traveled abroad to represent their husbands, but these were “goodwill” missions that might involve visiting troops, attending funerals, or witnessing how U.S. aid was being used to help those in need. In 1977, President Carter decided he did not have time to lead a mission to South America to talk about various policy matters, so he chose Rosalynn to go as his representative. His decision created a firestorm both in the United States and abroad. How could a woman, let alone one who had neither been appointed nor confirmed to a foreign policy position, be permitted to act as a stand-in for her husband and talk about sensitive diplomatic matters?

Neither President nor Mrs. Carter allowed such a question to change his mind. The first lady sat in on hours of foreign policy briefings, read as much as she could about the nations she was to visit, and took volumes of notes. During the trip, which involved visits to Jamaica, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Peru, Brazil, Colombia, and Venezuela, she addressed a wide array of topics, including economic difficulties faced by Jamaica and Costa Rica, Ecuador’s desire for military aircraft, Peru’s difficult relationship with Ecuador, Brazil’s human rights records, and Colombia’s involvement in the drug trade. There is evidence that her reports had some impact, such as the president’s decision to approve helicopters to Colombia to interdict drugs. Moreover, U.S. public opinion polls showed a generally positive response to her mission. Yet there remained objections to the president having sent his wife rather than, say, the vice president or a State Department official to lead that mission.

Mrs. Carter refused to allow criticism of her trip to deter her from continuing to act as her husband’s surrogate, advocate, and adviser on foreign policy matters. Following the signing of the Panama Canal Treaties in 1977 that turned the canal over to Panama, the first lady hosted luncheons to convince wavering senators to support ratification and even called some of their wives to get them to vote in favor.

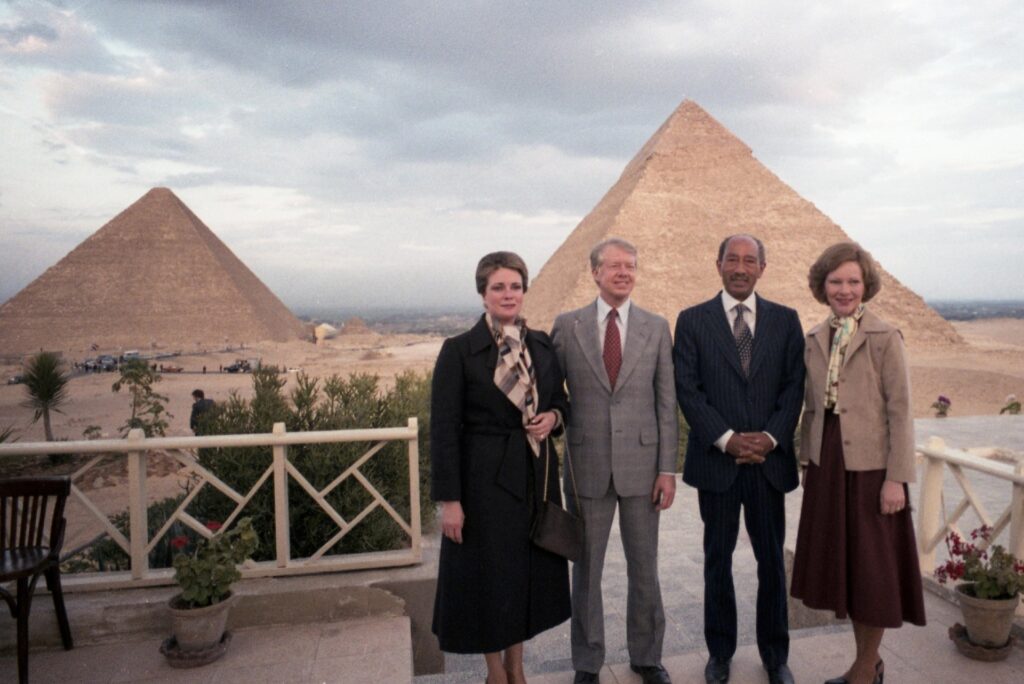

When President Carter invited President Anwar Sadat of Egypt and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin to Camp David for peace talks in September 1978, it was Mrs. Carter who suggested opening the negotiations with a prayer. After Begin and Sadat finally reached agreement on what became the Camp David Accords, she urged her husband to get the Egyptian and Israeli leaders to sign them immediately so they would not have second thoughts. In 1979, she proved instrumental in providing U.S. financial assistance for Cambodian refugees who had fled to Thailand to escape their repressive government, and she pressed the president to take a hard line against Iran after that nation seized dozens of American hostages. Finally, she aroused a hornet’s nest when it became public that she had tried to use contacts between the president’s brother, Billy, and the nation of Libya in an attempt to get the hostages released.

If her involvement in foreign policy matters drew criticism at times, so did Mrs. Carter’s appearance at cabinet meetings. This was actually her husband’s idea. The first lady had grown upset with some media reports about the Carter administration’s initiatives, and she had wanted to know if they were valid. Jimmy suggested, therefore, that she sit in on gatherings of his cabinet. While the first lady did nothing more than take notes, some in the media began to excoriate her for being present in a room where many of the country’s most sensitive domestic and foreign policy matters came up for discussion.

Given that Mrs. Carter had entered into realms considered off-limits for a first lady, and given that the president said that she was aware of virtually all that was happening in the administration, some critics began to ask who was in charge of the country. There were those who called her “Mrs. President.” Others, however, defended her, contending that she was the victim of sexism, and that her roles as adviser and advocate were no different than those of any wife.

For all the lines she crossed, though, Mrs. Carter remained popular, certainly more so than her husband. The president’s handling of domestic and diplomatic matters, be they his inability to stem inflation or the perception that he was weak when it came to containing the Soviet threat, had witnessed his approval numbers plummet. Mrs. Carter may have crossed some lines, but her advocacy for the mentally disabled and the elderly and her efforts to immunize children and get people to volunteer their time for any number of causes drew her praise. By the fall of 1979, a Gallup Poll found that over half of Americans disliked how President Carter was doing his job. Conversely, Gallup reported that nearly 60 percent of Americans liked how Mrs. Carter was “handling her role as first lady.” Indeed, in 1980, Rosalynn tied with Mother Teresa as the globe’s most admired woman.

After her husband’s defeat in the 1980 presidential election, Rosalynn joined Jimmy in their common pursuit of numerous causes. They became members of Habitat for Humanity, building homes around the world for low-income families. They founded the Carter Center in Atlanta, which has led efforts to eradicate numerous diseases around the world, promote democracy, and seek the peaceful resolution of disputes. Be it because of what she did while in the White House or what she continued to do afterward, Mrs. Carter ranked in the top ten among first ladies.

Reflecting on the Office of the First Lady

There remains, though, ambivalence surrounding the office of the First Lady. Nancy Reagan received barbs for having too much influence in her husband’s administration. An even better example would be Hillary Clinton, whom detractors scolded for leading her husband’s effort to reform the nation’s health care system. While some of the criticism had to do with the cost involved, there were those who argued that as an unelected, unappointed official, Mrs. Clinton had no right to involve herself in policymaking. Those first ladies who have leaned more toward the more traditional roles of hostess and social advocate have tended to avoid such criticism.

One recent study found, with rare exception, that first ladies in the modern era, including Mrs. Carter, are more popular than their husbands. As first lady, Rosalynn came under fire from many contemporaries who felt she had crossed the line regarding her proper role. But the fact that she remained more popular than her husband when he left the White House and, at the time of her passing, had far higher approval numbers than he, does raise questions about whether the president’s spouse should be given the opportunity to take on roles that might previously have been regarded as taboo.

Scott Kaufman is professor of history and a board of trustees research scholar at Francis Marion University. A more detailed narrative and analysis of the subjects covered in this essay can be found in his book, Rosalynn Carter: Equal Partner in the White House, published by the University Press of Kansas.