Join War on the Rocks and gain access to content trusted by policymakers, military leaders, and strategic thinkers worldwide.

More than three years ago, the U.S. government began its tepid response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Without a doubt, there have been missteps and challenges despite the fact that this was not the first time that the U.S. government has had to face a significant pandemic. The U.S. government has maintained a significant national security interest in biological threats since at least late 2001. The Department of Defense in particular has been developing pandemic and infectious disease strategies since at least 2009. Given the perceived stumbles by the Department of Health and Human Services in addressing this recent pandemic, the U.S. military took an unprecedented role in supporting the development and distribution of the COVID-19 vaccine. Now Department of Defense leaders are suggesting that the department should play a greater role in the nation’s efforts to counter natural disease outbreaks, both domestically and abroad.

On Nov. 1, 2021, Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin directed the department to prepare a Biodefense Posture Review that would “assess the biological threat landscape and establish the Department’s approach to biodefense.” Austin identified three main goals for the study — to unify the department’s biological research efforts, to modernize operations to improve readiness, and to synchronize biodefense-related planning with other government agencies to support national biodefense efforts. More than 21 months later, the report has finally been released, but it is simply not on par with the Nuclear Posture Review or Missile Defense Review. It offers no construct for countering adversary threats, has a tenuous connection (at best) to the National Defense Strategy, and gives no plan to modernize specific defense capabilities.

As the first of its kind, the Biodefense Posture Review does not examine military biodefense capabilities and does not illuminate the department’s readiness posture. Instead, it obfuscates the department’s biopreparedness concepts, takes authorities away from military agencies that address biological threats, and calls for duplicating efforts of other government agencies that have significant national biopreparedness roles.

This Biodefense Posture Review calls for a single governance structure, a Biodefense Council, to develop priorities and investment strategies, advise intelligence gathering, redirect budget activities, oversee the services’ exercises and readiness for biological incidents, and engage in industrial base discussions on the nation’s bioeconomy. This action is necessary not because the Department of Defense lacks authorities and defined roles for biodefense functions, but rather that it “could benefit from a more collective and unified approach” and needs to “strengthen integration mechanisms for situational awareness.” To execute this function, the Biodefense Posture Review uses poorly defined terms of reference, misrepresents existing defense concepts relating to biopreparedness, and ignores existing roles and missions of the Military Health System and the services’ acquisition and logistics offices.

Lack of Definitional Clarity

The basis for this review can be found in the Biden administration’s 2021 document American Pandemic Preparedness: Transforming Our Capabilities and the 2022 National Biodefense Strategy and Implementation Plan. Both documents direct U.S. government agencies to develop discrete capabilities to protect against biological incidents, whether naturally occurring, accidental, or deliberate. The focus of national guidance was appropriately on pandemic preparedness, given the nation’s struggle with containing the COVID-19 outbreak. Concerns about deliberate and accidental biological releases exist, but these threats have not resulted in any catastrophic incidents in the nation. Department of Defense leaders are tasked to protect their servicemembers, civilian workers, and military families on its many installations and bases from all three types of biological threats and are in fact performing those missions today. But in reading this review, one might be excused for not understanding that basic point.

The Biden administration’s National Biodefense Strategy identifies the Department of Defense as having lead and support responsibilities for a number of its goals. It is not a surprise, then, that the Biodefense Posture Review uses the same basic definitions as used in the strategy. However, the National Biodefense Strategy is inherently flawed due to its poorly defined terms of reference and lack of context as to how biological threats should be addressed. As defined in the strategy, biodefense includes all actions to counter (prevent), prepare for (protect against), respond to, and recover from bioincidents. These are the same general terms used in Presidential Policy Directive 8 “National Preparedness,” but it is unclear why the term “biopreparedness” was not considered, as it is used extensively in other government documents. It would have been a much more accurate term than biodefense.

The term “defense” has traditionally applied to protection and response against malicious actors, excluding prevention or recovery efforts. Prevention involves actions taken before a crisis while recovery addresses issues after a crisis — defense is what happens between prevention and recovery. There is a difference between how the military supports the federal response to a domestic terrorist incident and how it sustains operations given a biological weapons attack during wartime. The distinction is important if policymakers are to task the right defense agencies to develop discrete and vital biodefense capabilities for specific military scenarios. This clarity is absent in the review.

The review identifies a biothreat as an entity that causes a biohazard that leads to a bioincident. A biohazard is any biological substance that represents an actual or potential danger to people, animals, plants, or the environment. A bioincident is any act in which a biohazard threatens people. This circular logic complicates efforts to define distinct requirements needed to address specific threat sources (Mother Nature, a laboratory worker, an adversarial nation) and to designate which government agencies should receive funds to counter these threats. There are dozens if not hundreds of significant biological threats, and not all biological threats are national security concerns. The use of a generic term such as “biological threats” removes any rationale as to how federal funds should be allocated or how military capabilities should be developed. There is no “one size fits all” approach for protection and response across the spectrum of biological threats.

Clearly, the authors of the Biodefense Posture Review recognize that there are distinctions between naturally occurring biological threats, deliberate biological incidents, and laboratory accidents. It does warn the reader of adversarial nation intentions and the dangers of biotechnology advances that may lead to emerging biological threats, along with a heavy emphasis on the need for pandemic preparedness. And the Department of Defense already pursues these goals as detailed in directives on how force health protection, biological defense, and laboratory biosecurity are to be executed. At the same time, the review insists that there are “gaps, seams, and overlaps” across these areas that require a larger portfolio management effort to ensure that military forces are fully protected from the range of biological threats. However, it does not explain where these gaps, seams, and overlaps are.

There’s a particular emphasis on “emerging threats” and “threat-agnostic” medical countermeasures that the review says are required to ensure that the military can “more effectively and rapidly respond to biothreats.” The review calls for doing away with lists that prioritize biological warfare agents and natural diseases due to the possible emergence of “currently unknown or novel” biological threats. This idea of the destructive application of biotechnology is not new. Certainly the question of the origin of COVID-19, whether it was an emerging disease from natural origins, a bioengineered agent that escaped from a laboratory, or an intended biological weapon, plays into this discussion. This debate misses the important point, that COVID-19’s origin doesn’t matter as much as how the U.S. government improves its preparations for a future pandemic that threatens a civilian populace. This is a very different debate from how the U.S. military should develop biodefense capabilities to protect young, healthy troops during wartime. The challenge isn’t managing emerging threats, it’s determining who should get funds to address them.

Ignoring Strategic Missions and Goals

The review was tasked to “unify efforts” across the department, to “optimize capabilities” and “synchronize biodefense planning.” To many leaders that means tasking defense organizations to address the perceived public health gaps seen after the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. The review identifies three organizations — the Defense Health Agency, the Department of Defense Chemical-Biological Defense Program, and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency — as key players, but does not review the adequacy of the existing capabilities of the armed services to conduct force health protection, military biodefense, and laboratory biosecurity. The review does not mention the Army, Air Force, and Navy public health agencies, the U.S. Army Medical Institute for Infectious Diseases, nor special programs such as the Department of Defense’s Congressionally-Directed Medical Research Program, a significant biomedical research program for countering diseases. It offers no vision for future capabilities, as the Nuclear Posture Review and Missile Defense Review have.

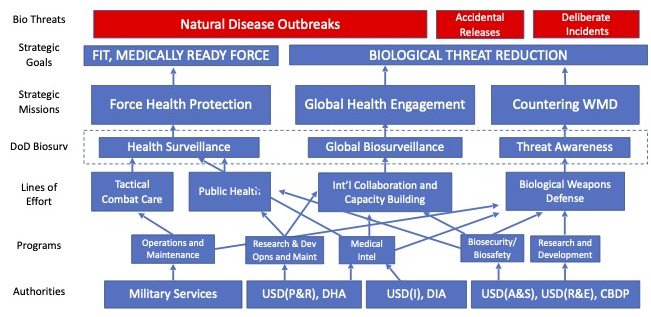

The Biodefense Posture Review suggests that a plethora of agencies and programs, each with its own directives and budgets, is the obstacle to optimizing biodefense capabilities. In fact, each organization has specific authorities and budgets because they create discrete capabilities for force health protection, global health engagement, and countering weapons of mass destruction (see Figure 1). Laboratory biosecurity, military intelligence, and biological research and development are supporting factors for all of these missions. There is a pandemic and infectious disease strategy separate from the countering weapons of mass destruction strategy because of the significant differences in mitigating a global pandemic versus countering an adversary with a biological weapon. The military services have a vested interest in maintaining their full combat potential by keeping people healthy, but that is a larger mission than simply disease prevention. It includes non-war-related accidents, self-inflicted wounds, combat injuries, and non-communicable diseases as well, all of which are part of force health protection. Most importantly, all of the services work together at the Defense Health Headquarters in Falls Church, Virginia. The Defense Health Agency already integrates and executes joint force health protection efforts, which includes disease prevention.

The Department of Defense’s Global Health Engagement effort has a distinct mission in that this area does not address the protection of U.S. forces from biological threats. It supports a broader U.S. government mission (led by Health and Human Services and complemented by the State Department) to help partner nations to build health capacity, combat emerging infectious diseases and antibiotic-resistant bacteria, and support humanitarian assistance and disaster relief missions. The department’s response to the West Africa Ebola crisis in 2014 was one such example of this mission. This effort is managed separately from military force health protection and biodefense so that it complements Health and Human Services’ lead role and does not impinge on the U.S. military’s efforts to protect its personnel from infectious diseases.

The Biodefense Posture Review emphasizes the need to increase biosurveillance capabilities, which is puzzling because (as the review itself notes) such a program already exists. The Defense Health Agency oversees the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Division that provides services to the military services and combatant commands, to include working with other government agencies to provide worldwide disease surveillance. It is tightly linked to disease surveillance programs in Health and Human Services, Homeland Security, and other agencies across the globe. The intelligence community recently renamed its National Counterproliferation Center to include biosecurity concerns in light of criticism as to its role in evaluating infectious disease outbreaks.

Military biodefense is a subcomponent of countering weapons of mass destruction and is funded separately from medical infectious disease research and development. There is a very good reason for why this division exists. In 1990, U.S. forces deploying to Saudi Arabia for Operation Desert Storm did not have enough anthrax or botulinum toxin vaccines. They also lacked automated detection systems to warn troops of any biological attack. In the 1980s, the Army’s medical agencies had made a conscious decision to move the bulk of their research funds to address natural infectious diseases and not biological warfare agents because the agencies judged natural diseases to be the greater risk to military forces. And if one were to look at the year-to-year impact of both threats, they were right, but this decision resulted in a very significant threat to U.S. forces when they fought an adversary with a biological weapons program. Despite this history and the lack of robust military biodefense capabilities, officials from the Office of the Secretary of Defense have repeatedly moved defense funds away from chemical-biological defense and to countermeasures for natural disease outbreaks over the past 15 years out of misguided desires to have Department of Defense research contribute to national public health efforts.

The review welcomes collaboration with other government agencies, notably Health and Human Services’ National Institutes of Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, but this is already happening. It fails to note Homeland Security’s National Biosurveillance Integration Center and National Biodefense Analysis and Countermeasures Center, and State’s Office of International Health and Biodefense. These agencies have put tens of billions of dollars into national biopreparedness objectives, particularly in early detection, global biosurveillance, and medical response activities. Where is the capability gap that the Department of Defense must address around significant national and international biological disease outbreaks, when these other agencies are adequately resourced and agile enough to do their missions?

The Drive for Efficiency

The overwhelming majority of biothreats come from natural disease outbreaks, and since the assistant secretary of defense for health affairs oversees the Defense Health Agency and its $37 billion annual budget, has the lead for Department of Defense’s Global Health Engagement, and is the lead for Department of Defense biosurveillance activities, one might believe that this is the right office to chair a Biodefense Council. In reality, the assistant secretary of defense for nuclear, chemical, and biological defense has been appointed as the Department of Defense executive secretariat for this governance vehicle, an office whose primary responsibility is facilitating the development of military requirements for nuclear weapons, as well as overseeing about a billion dollars in biological defense research and biological threat-reduction efforts. The review specifically targets the Chemical and Biological Defense Program to move its research toward pandemic preparedness, continuing a “spirit of competition” with the Defense Health Program. Given the review’s heavy focus on COVID-19 response, why is an acquisition office leading the review of these disease prevention concerns?

It may be that some officials in the department do not believe that the medical professionals understand defense policy enough to inform its direction, and in part this may be because the medical community does not do enough to engage on its own equities. For example, the Military Health Systems has seen significant challenges when competing against other defense priorities, even given the impact of COVID-19 and stated commitments to protecting the health of servicemembers. There is an inherent struggle between policymakers and scientists in writing, vetting, and implementing public policy measures. Particular to health policy, there is a challenge in executing evidence-based policy in that there can be a gulf between medical practitioners who focus on current best evidence to make recommendations about health care and policymakers who focus on politics and short-term decision-making contrary to science-based evidence. There is a danger of politicizing science if these actors do not agree on leading health topics. To a degree, this also extends to the relationship between the military medical community and defense policymakers.

The review calls for a “DoD-wide effort to develop and exercise scenarios that incorporate biothreats” and to “prioritize plans and training to improve readiness to meet requirements in a biologically challenged environment.” The report does not discuss the role of professional military education, an unfortunate absence. There are two significant challenges that will make this difficult. First, none of the armed services practice or train for engaging biothreats as a singular focus — they practice medical force health protection and chemical-biological defense as adjuncts to combat exercises. It has been traditionally very difficult to simulate an “attack” by biological organisms in any military exercise, which adds to the absence of realistic biodefense training. Second, there are limited funds allocated to training and exercises for the general force, and there are always other priorities that are higher than biodefense (unless the unit is question is a medical unit or an Army biodetection unit). No military unit ever failed a National Training Center deployment because it couldn’t do biodefense. The services are not going to increase training and exercise efforts unless funds are targeted specifically for this purpose, and that seems very unlikely.

The military services should have adequate stocks of critical biodefense supplies, respective to the context. Every servicemember should be prepared to operate in the context of biological threats, whether serving on a U.S. military base during a pandemic, fighting against an adversary that uses biological weapons, or working as a scientist in a government biological research laboratory. But this is a service responsibility to train, organize, and equip forces for future operating environments. The Office of the Secretary of Defense has an oversight role, but lacking any change in funding strategies, the services are going to have this responsibility. There are always questions as to the readiness of U.S. forces to protect themselves from chemical and biological weapons as well as to operate in a radiological-contaminated environment during wartime. These are known issues that the services understand and are responsible to address. There are already appropriate forums for these discussions — in the service headquarters, within the Joint Staff, and at the Joint Requirements Oversight Council.

Assistant Secretary of Defense Deborah Rosenblum recently described the need for a new governance structure to manage across “silos of centers of excellence” that resist the implementation of necessary investments and reforms short of direction from the deputy secretary of defense. It’s unclear that these silos are in fact the problem and that they require such a draconian solution. The services understand what they need, and they use the existing defense acquisition process to field required capabilities to meet national security objectives. The “silos” exist to ensure that these capabilities are developed in line with how the military organizes, equips, and trains its force. The joint staff surgeon, director operational test and evaluation, and the Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation offices assess how well those capabilities are developed. The processes identified in Department of Defense directives and instructions will work, if given the opportunity.

Conclusion

The defense leadership and, in turn, the national leadership should have a strong understanding of the Department of Defense’s capabilities to mitigate pandemic diseases, protect against the adversarial use of biological weapons, and reduce laboratory accidents. However, these three functions have never been managed under a single amorphous “biodefense enterprise.” There is a good reason for this, given that there are different defense programs tasked with countering the sources of these distinct biological threats. For defense policy to be successful, the government should clearly define roles and missions for defense agencies, which can then be translated into plans and budgets that meet specific policy objectives. Over the past 20 years, there have been recommendations to merge the Department of Defense’s medical biological research and development efforts for public health and military biodefense into one organizational structure out of a desire for efficiencies. None of these attempts have succeeded because they ignored how defense requirements and budgets are executed to meet national security objectives.

The national security community does need to prioritize and assess its efforts to develop capabilities against adversaries with biological weapons. The community used to understand this. At the same time, the community’s interest in public health issues has grown significantly. It started after the 2001 Amerithrax incident and has grown in scope with every pandemic that has hit the United States. But it is far from clear that the national security community understands the concept of health security at all. Health security is supposedly an overlap of concerns shared by the national security and public health communities, and yet it has not developed as a jointly understood issue as much as a vague concept of which both communities have been talking past each other. It is a mistake to think that the Department of Defense should do more for pandemic response using the Chemical and Biological Defense Program as a vehicle rather than the Defense Health Agency working with Health and Human Services, given its authorities and resources to address natural disease outbreaks.

The COVID-19 pandemic, as bad as it has been for the nation, has had a minimal impact on the armed forces’ day-to-day operational tempo. This is in no small way due to the existing force health protection measures that protect and maintain the fighting force and that, unless countered by congressional interests, work very well. The U.S. military does have a resilient capability to resist the impact of natural disease outbreaks, buttressed by Health and Human Services’ programs. The Department of Defense’s biosurety compliance program continues its good laboratory practices, having gotten through the few challenges of its recent past. What the military has traditionally called “biodefense” remains challenged by technical and budgetary limitations, but it needs to be developed as part of a larger countering weapons of mass destruction strategy, focused on protecting against biological weapons and not diluted with the vast demands of pandemic preparedness. These important functions need to be retained within their existing program elements and not lost under a generic biodefense construct and directed by an acquisition office.

This Biodefense Posture Review fails to advance our understanding of the national security community’s equities in public health issues or improve the department’s force health protection efforts. By imposing an artificial governance body over a significantly large and complex mission-set, the department is taking responsibilities away from the very offices that are working to advance these defense issues. If departmental leadership believes in “whole-of-government” approaches and the importance of not duplicating other government agencies’ capabilities, this Biodefense Posture Review needs to be critically re-assessed and refocused toward the Department of Defense’s core missions of force health protection, global health engagement, and countering weapons of mass destruction.

Albert J. Mauroni is the director of the U.S. Air Force Center for Strategic Deterrence Studies and author of the book BIOCRISIS: Defining Biological Threats in U.S. Policy. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Air Force, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.