Move Soldiers Less: A Divisional System in the U.S. Army

The Army spends over $1.8 billion on permanent change-of-station moves annually. That’s 40 percent of what the Army receives each year to purchase weapons and tracked combat vehicles, nearly as much as its fiscal year 2024 investments to modernize long-range fires or create modern air defenses, and approximately twice as much as it plans to spend on building new barracks or improving its pre-positioned stocks.

Beyond cost, the Army’s current model of career development also inhibits spousal employment. Survey data indicates that military spouses experience unemployment rates above 20 percent, despite having a higher level of education on average than the general population. Both spousal unemployment and underemployment undoubtedly contribute to nearly 25 percent of servicemembers expressing some level of food insecurity. Then there’s the cost on children, who often find themselves at the bottom of long waitlists to enroll in new schools or childcare centers. This barely begins to address the turmoil that results from moving families away from their social networks at two-to-three-year intervals, or the expense, time and effort required to relocate a household.

Adopting a divisional system could save money for the military and improve satisfaction and retention among servicemembers — many of whom leave under pressure from family members who want geographic stability. Instead of repeatedly moving between units, soldiers would be assigned to a division upon entering the Army. Enlisted soldiers who aligned themselves to a division, with its nearly 16,000 different positions, would have adequate opportunities to promote to master sergeant (E-8) or even sergeant major (E-9) in nearly any military occupational specialty. Even officers would have the ability to achieve lieutenant colonel (O-5) and possibly colonel (O-6) in many career fields. Adoption of a divisional system in the U.S. Army has the potential to reduce the cost of permanent change-of-station moves, increase unit cohesion, promote stronger local communities in and around military bases, and reduce the disruptions of military life on families.

A Changed World

Many of the issues with repeatedly moving soldiers to new duty stations were previously mitigated by the strength of military communities. Soldiers arriving at a new installation could expect to find a robust, welcoming reception. Weekly socials at officer and non-commissioned officer clubs, quality on-post housing, and lively community events on Army installations were hallmarks of Army life.

Unfortunately, Army posts are no longer as vibrant. Security reforms implemented after 9/11 limit interaction with the local community. Clubs have long been in decline, and the questionable value of on-post housing leads many officers and non-commissioned officers to buy off-post. Some Army installations still offer a good quality of life and a strong community, but many of the aspects of Army life that made frequent moves more bearable have faded.

Moving the U.S. Army to a divisional system could directly counter these negative developments. Soldiers stationed at a single post for most of their careers would form strong attachments to their local community and they would have additional incentives to invest in the cities, schools and civil life around their posts. Money the Army currently spends on moves could instead be used to beautify and improve post structures, housing, and schools. Furthermore, keeping soldiers in the same division would cause them to develop more cohesive teams and social relationships, improving both the working environment and the effectiveness of units under the division. The Army’s current system emphasizes exposing soldiers to diverse experiences, but at what cost? The value of cohesion must be considered, and new methods for soldiers to gain new experiences found.

Life in a Divisional System

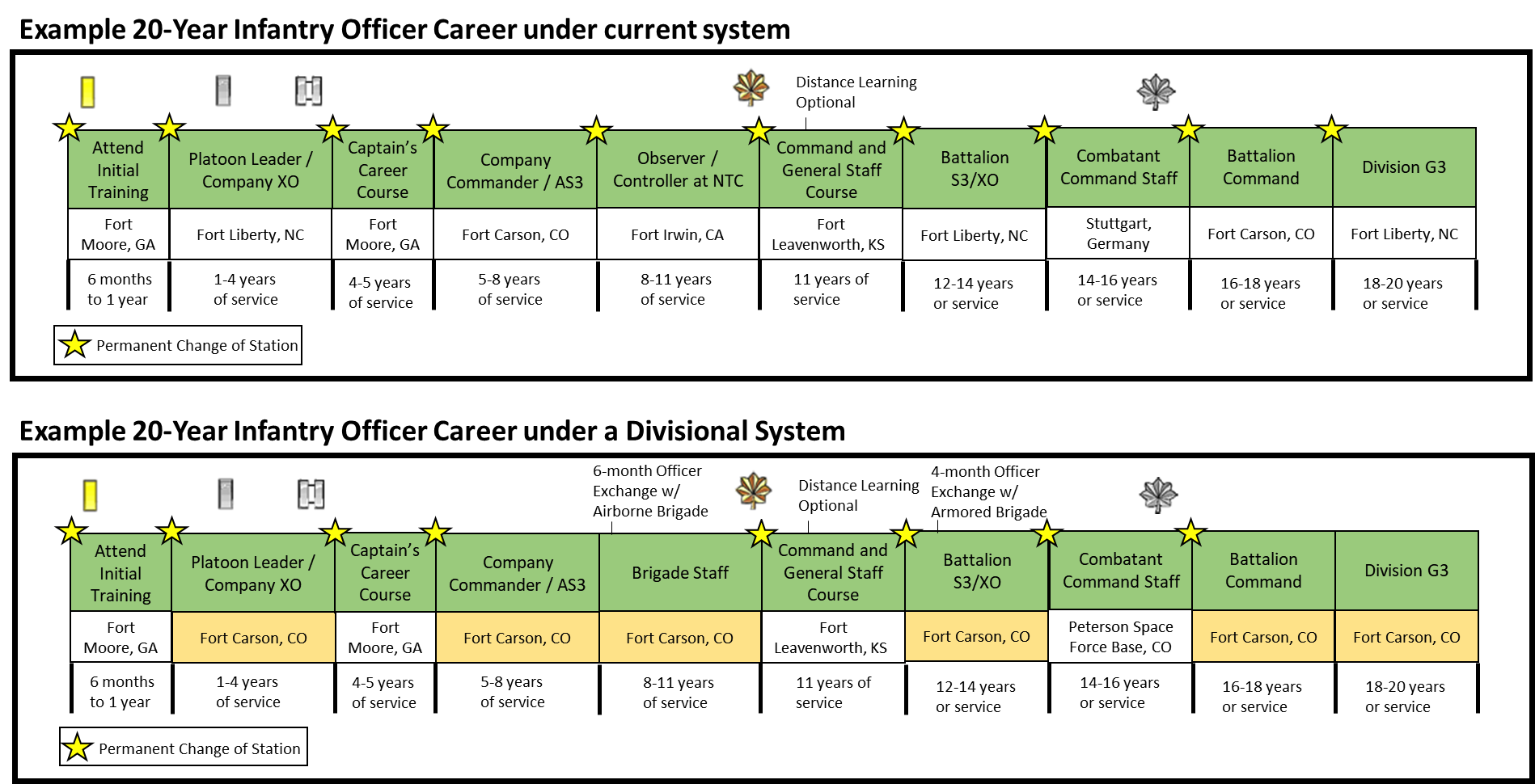

Under the current system, an officer or non-commissioned officer can expect to move at least 10 times during a 20-year career. Some careers require more frequent moves, some less. In a divisional system, that same officer could reduce the number of moves that their family experiences and spend over three-quarters of their career (15–18 years) at a single duty station. An officer could increase this further by completing their command and general staff college through distance learning or a shortened satellite course, and by foregoing joint duty assignments if they did not plan to compete to be a general officer. In sum, a divisional system has the potential to allow an officer or non-commissioned officer to stay in a single location — except for deployments, professional military education, and temporary duty assignments — while still having a full career.

Sample timelines of an officer’s 20-year career under the current stationing construct and under a divisional system. Prepared by the author.

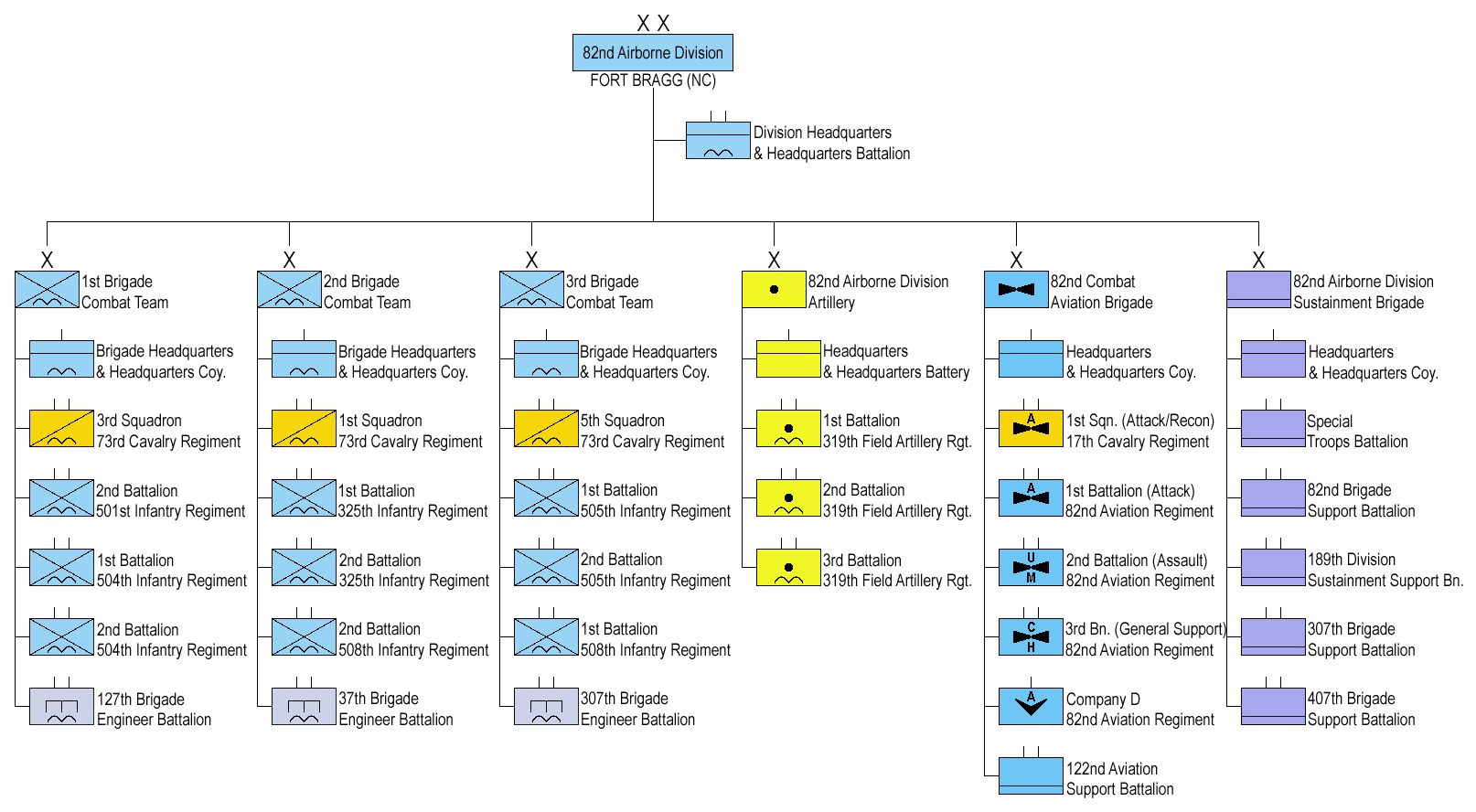

Keeping an officer or non-commissioned officer at a single division would do little to harm their advancement up to the rank of lieutenant colonel (O-5) or master sergeant (E-8). Infantry divisions contain six different brigades: three infantry, one artillery, one sustainment, and one aviation. Each of these is an O-6 command. Within every infantry brigade, there are seven battalions or O-5 commands: three infantry, one support battalion, one engineer battalion, one artillery battalion, and one cavalry squadron. At the rank of captain (O-3), command opportunities are even greater. A single infantry brigade combat team has 15 infantry companies, nine logistics companies, four cavalry squadrons, four artillery batteries, three engineer companies, and singular medical, signal, and intelligence companies. Lieutenants, captains, and majors can easily move between battalions and brigades within the division’s structure to obtain the key staff and command assignments they need to professionally develop.

An example of a division and its structure. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Enlisted soldiers can easily serve full careers under a divisional system as well. Each brigade and battalion in the division’s structure contains a billet for a sergeant major (E-9), the terminal enlisted rank. The dozens of companies in a division each provide opportunities for soldiers to serve as first sergeants (E-8), a rank that often marks the end of a respected career. An enlisted soldier, even in a lower-density career field like intelligence, could easily move between the three to four intelligence companies within a division to serve as a team leader, squad leader, and platoon sergeant, while they round out their experience serving on battalion, brigade, and divisional staff in S2 sections (intelligence). Denser career fields — like infantry, armor, artillery, and logistics — would have robust opportunities to move around internally.

In addition to the stability a division-centric career offers, this system could also do much to create traditions, instill pride, and build a sense of history. Great leaders already attempt to do these things, but it is difficult to achieve during a two-to-three-year assignment. Keeping soldiers on station for longer will allow much of this to occur organically, thereby strengthening the culture already in place.

Flaws in the System

A divisional system would not, of course, solve everything. It would provide ample opportunities for combat arms soldiers and logisticians. But lower-density career fields like cyber, finance, medical, signal, functional areas, and other critical enablers may not be able to avoid significant moves through a 20-plus-year career. The British Army deals with lower-density fields like this by assigning them to corps, in which duty stations change in a similar pattern to the U.S. Army.

If the Army wanted to provide servicemembers in these lower-density career fields additional stability, they could offer them the opportunity to at least begin their careers in a division (or independent brigades or battalions). A signal officer, for instance, could likely stay within a division or brigade to the rank of major (O-4) before they would need to join the signal corps and accept assignments at the requirements of the service. Alternatively, the Army could seek to extend the length of assignments for lower-density specialties, making them four to seven years at a duty station. Either method, or a mix of them, would provide additional geographic stability.

And what about the servicemembers who like to move frequently? They still could. Any divisional system would require a method for soldiers to transfer between divisions. While divisional staff would quickly develop methods to screen soldiers for “fit,” as they have for the Army’s assignment interactive module, no system is perfect. Moreover, life circumstances may drive a soldier and his or her family to desire a change of scenery. One method of creating this mobility between divisions would be to keep 20 percent of all billets in a division reserved for soldiers from outside it. This would allow soldiers to try life in a different division and provide broadening experiences by exposing them to different geographic environments, mission sets, and force structures.

Other opportunities to move would come from the need to fill billets at headquarters, corps, independent detachments and companies — not to mention within the interagency, independent commands, internal agencies and joint commands. Most positions could be filled by volunteers, but some moves would still undoubtedly need to be mandated.

Much of the moving that soldiers do today occurs to provide them with different experiences. Artillerymen rotate between cannon and missile units, infantrymen do tours in light and mechanized formations, and logisticians serve at different echelons and in different specialties to develop holistically. Many of these experiences can be replicated within a division — the National Guard, for example, manages to develop officers under a divisional footprint — but others cannot. Still, in lieu of sending officers and non-commissioned officers off to joint or higher headquarters assignments, they could also consider giving them an opportunity to lead units outside of their basic branch. An infantryman could lead a logistics company for a year or two and better develop a complete sense of how the Army sustains combat operations. Ensuring officers and non-commissioned officers have these diverse experiences may also require something like an exchange program, where soldiers from different divisions and units switch places for four to six months of temporary duty.

If the Army had concerns about soldiers becoming overly specialized or tribal, it could create a divisional construct that shields younger non-commissioned officers and enlisted soldiers from moving frequently, but still requires officers and senior non-commissioned officers to regularly change stations. A soldier could stay at the same division until he or she reached sergeant first class (E-7), but to accept promotion to master sergeant (E-8), that individual would need to change stations to a new unit. Under this model of a divisional system, officers could either have longer assignments at duty stations, be assigned to divisions up to the rank of major (O-4), or rotate every two to three years as they do under the current system. This would shield the most financially vulnerable servicemembers from frequent moves and ensure that divisions retain a fresh influx of leaders with diverse experiences from other units. Officers and senior non-commissioned officers control training and unit standards. Rotating them into divisions under this model would ensure that best practices and different perspectives continue to be exchanged across the Army.

Conclusion

Like every system, a divisional construct would have tradeoffs. The Army’s current method of stationing and developing personnel helps expose soldiers to a variety of units in different geographic locations. A private in the 25th Infantry Division might learn about jungle fighting before becoming a non-commissioned officer at the 11th Airborne Division and training for Arctic warfare.

There’s no doubt that this has value. The question is, how much? And how does that value compare with the value of keeping soldiers in the same environment longer so they can develop true expertise? Or of providing geographic stability for a soldier and their family? Or drastically reducing how much money and time the Army spends on moving soldiers between duty stations?

At a minimum, the adoption of a divisional system deserves study. Moving at two-to-three-year intervals over the course of a 20-plus-year military career places extreme strain on families and soldiers. Under a divisional system, those who wanted to move frequently still could, while those who desired more stability could find it. Life has changed over the past 50 years. Army families no longer live solely in tight-knit communities on base, and most American households now consist of dual-income families. Adopting a divisional system could simultaneously strengthen the service, foster tradition, and accommodate the realities of 21st-century society.

Lieutenant Colonel Jules “Jay” Hurst is an army strategist. He currently serves as a legislative liaison. He would like to express his thanks to Lieutenant Colonel Alex Wray for the conversation that led to this idea.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or U.S. government.

Image: U.S. Army photo by Christian Marquardt, 7th Army Joint Multinational Training Command