Biden’s Asia Diplomacy Is Still Incomplete

Images of President Joe Biden, South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol, and Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida together at Camp David are a powerful reminder of the progress that the Biden administration has made with key allies and partners in recent years. Washington has made some notable achievements, from this meeting to the reinvigoration of the Quad, establishment of AUKUS, and basing deals with the Philippines and Papua New Guinea. Still, it is hard to give Biden more than an incomplete grade for his approach to the Indo-Pacific.

U.S. policy elsewhere in the region appears stuck in neutral, particularly in Southeast Asia. Five years ago, I suggested that the Donald Trump administration’s approach to the Indo-Pacific could be described as “a tale of two Asia policies” — the United States had been successful in some domains yet was failing badly in others. Today, this is still true. Regional leaders are deeply disappointed by America’s rejection of trade liberalization as well as its inconsistent diplomatic engagement. Biden’s head-scratching decision to skip this year’s East Asia Summit and Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) meeting in Indonesia will raise many eyebrows.

How can the United States make so much progress in some parts of the Indo-Pacific yet struggle elsewhere? The answer is simple: the Biden team has excelled at pushing open doors unlocked by Beijing’s overreach in the security sphere. Leaders in Beijing blame Washington for “containment, encirclement, and suppression,” but the reality is that Chinese leaders are largely to blame for their own regional predicament. But where China appears less threatening, the task is not so simple because U.S. leaders appear unwilling to provide the types of economic and diplomatic engagement many partners seek. Washington has picked the low-hanging fruit; what’s left now will prove more difficult to reach.

Beijing Coerces, Biden Capitalizes

The United States has made some remarkable progress with key Indo-Pacific countries in the last few years. In the first eight months of 2023, Biden has already hosted his Japanese, Korean, Philippine, and Indian counterparts in Washington and has also launched major initiatives with Australia and Papua New Guinea. But Biden’s biggest breakthroughs have been made possible by China’s deep unpopularity triggered by its aggressive overreach. Consider the following initiatives:

AUKUS

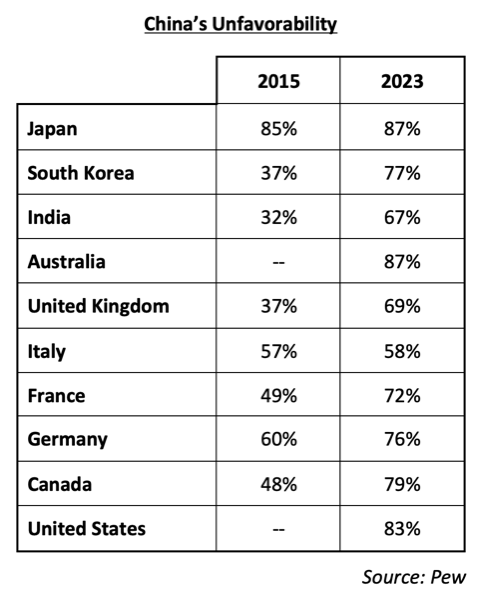

The Australian-U.K.-U.S. arrangement occurred after China’s unpopularity spiked in Canberra and London. In the United Kingdom, China’s unfavorability rose from 37 percent in 2015 to 69 percent in 2023, due in part to Beijing’s repression in Hong Kong. Meanwhile, in Australia, the percentage of Australians reporting that China was more of a security threat than an economic partner rose from 15 percent in 2015 to 63 percent last year, after a prolonged economic coercion campaign by China.

Quad

The Australian-Indian-Japanese-U.S. quadrilateral arrangement was also enabled by an increase in China’s unfavorability. In India, 32 percent had an unfavorable view of China in 2015, but after Beijing’s reckless violence on the Sino-Indian border, that figure increased to 67 percent in 2023. In Japan and Australia, China’s unfavorability in 2023 stood at 87 percent, higher even than China’s 83 percent unfavorability in the United States.

Trilateral

The Camp David summit between Japan, South Korea, and the United States would not have been possible without China’s economic coercion against South Korea. Beijing’s unfavorability in Seoul rose from 37 percent to 77 percent from 2015 to 2023, due in large part to China’s reaction to South Korea’s decision to place a missile defense battery on the peninsula.

Philippines

The United States has also made notable progress with the Philippines, including a new base access arrangement announced in April. There, too, Beijing has overreached, with its pressure on Manila leading to the highest preference for the United States over China (78.8 percent) among all experts in Southeast Asia. Beijing’s coercion at Second Thomas Shoal is only likely to accelerate this dynamic.

G7

Although it is not an Indo-Pacific group, the G7 has taken a series of surprisingly strong stances on China in recent years. China’s domestic repression and support for Russia are key factors. In 2015, China’s unfavorability stood at 37 percent in the United Kingdom, 48 percent in Canada, 49 percent in France, 57 percent in Italy, and 60 percent in Germany. By 2023, those figures had risen to 69 percent in the United Kingdom, 79 percent in Canada, 72 percent in France, 58 percent in Italy, and 76 percent in Germany, to say nothing of Japan and the United States.

To be clear, China’s unpopularity may be necessary for America’s progress with AUKUS, the Quad, the Trilateral, the Philippines, and the G7, but it is by no means sufficient. The Trump team capitalized on the opportunity with the Quad, and the Biden team has smartly built on that progress and added several major new initiatives. These recent diplomatic achievements have been impressive. But Americans must recognize that Washington’s success is due in no small part to Beijing’s overreach. Recent U.S. progress therefore remains focused on those countries most concerned by China’s assertive security behavior. Although these countries account for a substantial portion of global economic production, much of the rest of the region does not share their degree of concern about China, so there are real challenges ahead, particularly in Southeast Asia.

America Stumbles, ASEAN Hedges

Although the Biden team has done an excellent job of capitalizing on opportunities presented by China, there is reason to be concerned that additional progress may prove more difficult. Biden’s diplomatic engagement and trade strategy are not attracting much support in the rest of the Indo-Pacific, particularly in Southeast Asia. Expectations may have been unfairly high, but it should be a warning sign that 60 percent of Southeast Asian experts report that U.S. engagement with the region has decreased or remained unchanged under the Biden administration.

To understand why, one need only review diplomatic engagement in Southeast Asia. When Biden attended his first ASEAN Summit as president in 2021, he promised, “You can expect to see me personally showing up and reaching out to you.” In 2022, he told ASEAN leaders that they were “at the heart of my administration’s Indo-Pacific strategy.” In 2023, however, he won’t be able repeat either of those promises at the ASEAN Summit, because Biden won’t there or at the East Asia Summit.

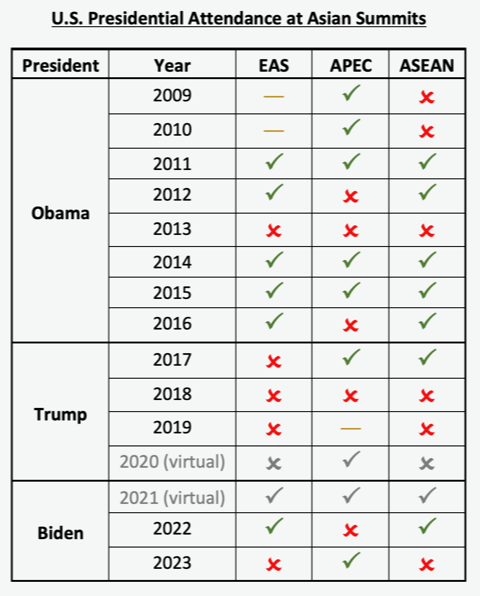

Coming so soon after Biden cancelled trips to Papua New Guinea and Australia, the decision not to attend the summits in Indonesia will be seen as another sign of inconsistent U.S. engagement. National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan described “reengaging with ASEAN and APEC as cornerstones of our engagement in the Indo-Pacific.” But Biden also did not go to the last Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation Summit. Thus far, Biden’s attendance record looks more like that of Donald Trump than Barack Obama.

President Obama made it a point to attend the yearly Asian summits, going to 15 of 22 (68 percent) of the in-person meetings and skipping them entirely in only one of his eight years. President Trump only made it to two of eight (25 percent) in-person summits. Many expected that Biden would mark a return to Obama’s approach, but he will have gone to only three of six meetings in person. And the United States hosts the Asia-Pacific Forum this year, so he hardly gets credit for attending.

Once again, it seems that Washington is saying one thing and doing another. What makes this particularly strange is that Indonesia is such an important player. It is home to over 275 million people, behind only India, China, and the United States. Indonesia accounts for roughly a third of economic production in Southeast Asia. And its leadership within ASEAN and geographic position astride numerous maritime chokepoints make it a vital strategic partner. Even more confusingly, Biden is going to Vietnam on the trip that was supposed to include Indonesia, so it appears that this is a conscious decision to downgrade ties with ASEAN’s biggest country.

In addition to this apparent diplomatic downgrade, the administration continues to get an incomplete grade in the economic arena. Biden did not withdraw the United States from the Trans-Pacific Partnership — that was a decision made by Trump. But Biden has followed Trump’s lead by being unwilling to discuss new trade deals. Instead, the United States is offering the region an Indo-Pacific Economic Framework focusing on aligning standards and regulations. The administration argues that a “new Washington consensus” on trade will “build a fairer, more durable global economic order.” Yet few in the Indo-Pacific want this new consensus — what they seek is access to the large and thriving U.S. market.

As Singapore’s ambassador to the United States said, “When you don’t have market access, there’s no real trade policy. … The countries of the region are somewhat disappointed that we’re not getting the kind of trade agenda that we would have liked from the U.S.” The Biden team is unlikely to reverse course, even though it looks likely that China will eventually join the Comprehensive and Progress Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership. Unless Washington gets off the sidelines, most in Southeast Asia will therefore remain skeptical of U.S. economic engagement.

Time to Finish the Assignment

How will observers in Southeast Asia and beyond make sense of these dynamics? If trends continue, foreign leaders could come to believe that public opposition to China is the litmus test for consequential U.S. engagement. U.S. leaders appear to have a two-tiered regional approach: ambitious engagement with countries that are openly balancing against China, but limited time for those countries that prefer to hedge. In short, Biden is investing in the balancers but not the hedgers. Relationships with Washington could therefore appear transactional and instrumental, which is an accusation often launched against Beijing. There is a real danger that this will undermine the Biden team’s own messaging in its Indo-Pacific strategy, which described American interests in the region as being independent of its rivalry with China.

The United States cannot succeed in the broader Indo-Pacific region if it appears to expend time and energy only on those countries willing to openly balance against China. By skipping the ASEAN and East Asia summits in Jakarta, Biden will raise questions about American strategy and reliability. Perception in the region will be that the United States is downgrading ties with Indonesia over its unwillingness to sign up for initiatives that might be perceived as undermining Jakarta’s strategic autonomy. The task for the Biden team in the next year will be to undo this impression from Indonesia to Singapore to New Zealand to the Pacific Islands. Doing so without a robust trade policy will be challenging.

The World Cup may just have finished, but Biden is about to score an own goal by skipping this year’s ASEAN meeting and East Asia Summit. Washington must change its approach to convince regional players that it will be a reliable partner across the Indo-Pacific.

Zack Cooper is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and a lecturer at Princeton University. He co-hosts the Net Assessment podcast for War on the Rocks

Image: The White House