China and the Alliance Allergy of Rising Powers

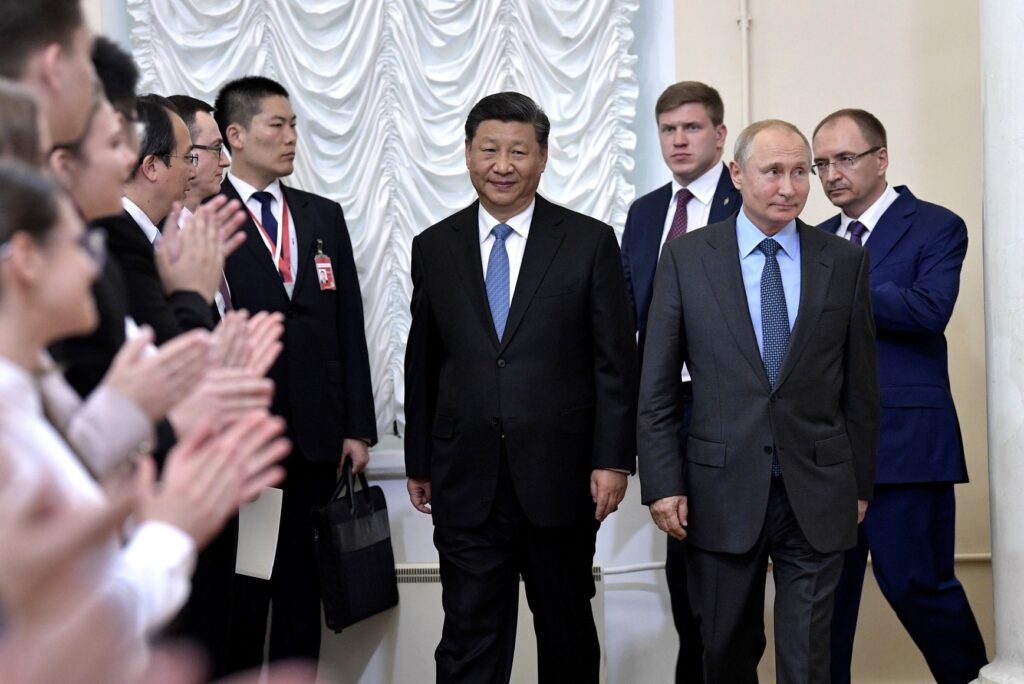

The outcomes of two recent high-profile summit meetings exposed the yawning gap in U.S. and Chinese leaders’ attitudes toward military alliances. On March 13, U.S. President Joe Biden met British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak and Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese in San Diego to formalize the trilateral AUKUS partnership. AUKUS considerably deepens America’s existing alliances with Britain and Australia by committing the United States and Britain to help Australia develop and deploy a fleet of nuclear-powered submarines. Then, on March 20, Chinese leader Xi Jinping met with Russian President Vladimir Putin in Moscow. Although Xi loftily proclaimed that his visit heralded “a new era” of Sino-Russian cooperation, the meeting’s accompanying statement only committed the two states to such meager cooperative activities as the “joint production of television programs.” Not only did Xi continue to refrain from concluding a formal alliance with Russia, the world’s other leading revisionist power, he even continued to deny the Kremlin military assistance to support its faltering war effort in Ukraine.

Considering the ability of allies to tilt the balance of power between a hegemonic state and a rising challenger, it seems puzzling that the People’s Republic of China has refused to abandon its longstanding policy of eschewing alliances. Yet history shows that China’s behavior is not anomalous, as all four rising great powers of the last century — Germany, the United States, Japan, and the Soviet Union — also exhibited what could be termed an “alliance allergy.” Rising powers are uniquely inclined to devalue alliances, particularly with other powerful states. They are exceedingly confident in their ability to singlehandedly achieve their expansive international goals and reluctant to compromise on them. A clearer understanding of this phenomenon can ease the concerns of U.S. policymakers about the scale of the threat posed by China, enabling them to craft a more prudent strategy for managing simmering tensions in East Asia.

China’s Non-Alliance Policy

Beijing has only concluded two standing alliances in its history — with the Soviet Union in 1950 and with North Korea in 1961. In 1982, the Chinese Communist Party officially adopted an “independent and self-reliant foreign policy of peace” at its 12th Party Congress. At the 14th Party Congress convened a decade later, then-President Jiang Zemin pointedly reiterated that China “will not enter into alliance with any country or group of countries and will not join any military bloc.” Party officials and Chinese scholars echoing the party line have offered several rationales for this policy. First, alliances can entrap their signatories in unnecessary wars. Second, China has few viable allies because most nearby states are militarily weak. Third, Chinese alliance-building would perversely increase regional tensions and lead neighboring states to oppose China. And finally, alliances are incapable of addressing non-traditional security threats.

Although these admonitions are hardly absurd, China’s continued adherence to a non-alliance policy undermines its ability to contest U.S. hegemony even though its economy is about as large as that of the United States and enjoys a higher annual rate of economic growth. According to political scientist Glenn Snyder, formal military alliances represent the most reliable and effective form of multilateral security cooperation because they include “elements of specificity, legal and moral obligation, and reciprocity that are usually lacking in informal alignments.” Whereas the United States is allied with 50 countries that collectively account for over one-third of global economic output, China’s sole remaining alliance partner is the perennially failing state of North Korea. America’s six East Asian allies alone — Japan, South Korea, Thailand, the Philippines, Australia, and New Zealand — collectively spent $149.7 billion on defense in 2021, amounting to half of China’s estimated $293.3 billion defense budget. By contrast, North Korea spent a mere $4 billion on defense in 2019 (the last year for which official estimates are available), amounting to 0.5 percent of the $732 billion U.S. defense budget for that year.

Great Powers Go It Alone

A survey of the behavior of each of the rising great powers of the last century demonstrates that China’s aversion to formal military alliances is not idiosyncratic. Germany, the United States, Japan, and the Soviet Union all exhibited an “alliance allergy”: They were lax in recruiting powerful states as allies and they alienated those powerful states that they managed to enlist as allies by behaving dismissively and domineeringly toward them. In each instance, the allergy became increasingly acute as the rising power’s wealth and military capabilities expanded.

Rising great powers are uniquely susceptible to the alliance allergy for two reasons. First, since rising powers are by definition extremely large and populous states experiencing rapid economic growth, they will be extremely confident that they can unilaterally generate the military capabilities required to topple a hegemon in relative decline. Second, a rising power will also strive to avoid making painful ex ante compromises with allies on the blueprint for the international order it seeks to impose upon attaining regional or global hegemony. According to the political scientist Robert Gilpin, an international order consists of “the rules governing the international system, the division of spheres of influence, and … the international distribution of territory.” The rising challenger will seek to monopolize these arrangements from the outset because they both reflect and promote the dominant state’s interests and values over the long term. This explains why a rising power will be even more reluctant to partner with a powerful state than a weak one — the former may be more valuable than the latter in the effort to supplant the prevailing hegemon, but it will demand a more prominent role in the composition of the subsequent international order.

Germany and the United States During World War I

By the time World War I dealt the first body blow to the Pax Britannica, both Germany and the United States had already eclipsed the British hegemon in industrial might and evinced a strong disregard for allies. In the two decades that preceded the war, Germany’s expansionist policy of Weltpolitik had already resulted in its estrangement from the two most powerful states with which it could have allied against neighboring arch-adversary France. First, in 1890 Kaiser Wilhelm II and his coterie permitted Germany’s defensive Reinsurance Treaty with Russia to lapse. Then, later that decade, they rebuffed the British hegemon’s entreaties for an Anglo-German alliance, instead initiating a naval arms race against London. Russia proceeded to strike an alliance with France, while Britain settled its colonial disputes with France and Russia. These developments laid the groundwork for the Triple Entente that would confront and defeat Germany in the coming war.

Germany also estranged itself from its sole great power ally, Austria-Hungry, with which it had initially partnered in the 1879 Dual Alliance Treaty. In the years that preceded the outbreak of World War I, German officials concealed from their Austro-Hungarian counterparts a fundamental reorientation of the German war plan, which envisioned an opening offensive primarily directed at France rather than Russia. After the war began, German military leaders treated their Austro-Hungarian counterparts with unrelenting derision, imposing German command on Austro-Hungarian forces and attempting to lure Italy and Romania into neutrality by offering them slices of Austro-Hungarian territory. The fractious alliance reached its nadir in early 1917 when Berlin rejected Vienna’s demand to publish a joint set of peace terms, which prompted Hapsburg Emperor Karl I to secretly pursue a separate peace with the Entente.

Germany’s contemptuous behavior towards its most important ally was driven both by arrogance and by reluctance to share the anticipated postwar spoils. German arrogance was reflected in the private comments of Gen. Erich Ludendorff comparing Austria-Hungary to a “corpse” and complaining about the empire’s military “worthlessness.” Germany’s reluctance to share the spoils was reflected in its 1916 decision to bully Austria-Hungary into renouncing its key war aim of annexing Poland, which conflicted with Germany’s goal of seizing Poland’s industrial regions for itself. It was additionally evident in Berlin’s plan to construct a Central European customs union (Mitteleuropa), which Vienna feared would result in the Dual Monarchy’s economic and political disintegration.

Meanwhile, although the United States eventually fought in the war alongside the British hegemon, it did so in a manner aimed at maximizing Washington’s independence. Upon entering the war in April 1917, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson insisted that the United States was only relinquishing its previous neutrality to join the Entente as an “associate” rather than an “allied” power. Wilson proceeded to reject desperate British and French pleas to rapidly integrate U.S. troops into their armies and instead insisted on keeping U.S. divisions intact and under American command. This highly inefficient deployment plan recklessly elevated the risk that the Germans would overrun the tenuous Allied positions on the Western Front before U.S. troops could enter the fray in sufficient numbers to turn the tide.

Wilson’s actions stemmed from his conviction that U.S. forces could independently determine the war’s outcome and his utopian liberal vision for a postwar international order based on democracy, free trade, self-determination, and collective security. The discrepancy in war aims between the United States and its co-belligerents was most glaringly evident in Wilson’s public assurance to Germany that “we do not wish to injure her or block in any way her legitimate influence or power.” This pledge contravened secret Entente agreements to annex German territory, parcel out its colonies, and exact onerous reparations payments from Berlin. Such frictions would later play out disastrously at the postwar peace negotiations in Paris, resulting in a treaty that was too harsh for the unconquered Germans to accept but insufficiently harsh to prevent them from seeking revenge.

Germany, Japan, and the United States During World War II

During the interwar decades, the leading contenders to replace an exhausted Britain as hegemon were once again Germany and the United States, the only two states that exceeded Britain’s share of world manufacturing on the eve of World War II. Although Imperial Japan was not in the same economic league as those three states, it had emerged as the leading military and industrial power in Asia. Although Germany and Japan were nominally allies bound by their 1940 Tripartite Pact with Italy, they conducted no joint operations, undertook no joint planning, shared minimal intelligence, engaged in virtually no trade or mutual military assistance, and kept secret from one another their most fateful strategic decisions of the war. Nazi Germany also forfeited a monumental opportunity to win the war in late 1940 by rejecting a Soviet request to join the Tripartite Pact, even though the addition of the Soviet Union to the Axis would have been devastating to Britain and the still-neutral United States. After the Wehrmacht’s subsequent invasion of the Soviet Union bogged down in 1942, German dictator Adolf Hitler ignored Japanese and Italian appeals to make peace with the Soviets and concentrate German forces against the United States and Britain. For its part, Japan refused repeated German requests to abandon Japan’s 1941 neutrality pact with the Soviets due to its preoccupation with expanding its maritime empire in Southeast Asia.

The Axis’ two most powerful members hardly cooperated with one another due to their leaders’ blinding self-confidence and exclusionary visions for a postwar international order. In Hitler’s 1925 autobiography Mein Kampf, the future German Führer laid out a four-stage plan, which consisted of the sequential conquest of Central Europe, Western Europe, the Soviet Union, and the United States. By late 1941 Germany had almost singlehandedly surmounted the first two stages and was on the cusp of surmounting the third. For Hitler, Japan not only posed a long-term geopolitical danger by standing in the way of German global supremacy, but also comprised a racially inferior population that would inevitably have to be enslaved or exterminated by the Aryan master race. Japan’s early wartime victories in Asia produced an equally exaggerated perception on the part of its militarist leaders that they could unilaterally achieve their sweeping territorial ambitions, which encompassed India, the South Pacific, Alaska, Western Canada, Central and South America, and even the Northwestern United States. The ideological doctrine of kodo that held sway among Japanese elites also militated against close ties with Germany, as it stipulated that Japan’s mission entailed overcoming historical subjugation to the Western colonial powers and realizing Japan’s destiny as a superior people and culture.

Following its late entry into the war in December 1941, America’s behavior towards its Grand Alliance partners, Britain and the Soviet Union, became ever less cooperative as its initial dependence on those states’ more numerous fighting forces diminished. In the two years that followed Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt acquiesced to a “Europe first” strategy prioritizing the defeat of Germany, authorized the creation of an Anglo-American Combined Chiefs of Staff system to direct wartime strategy, permitted Anglo-American operational unity of command arrangements in most combat theaters, and furnished both allies with billions of dollars of Lend-Lease military assistance. Beginning in early 1944, however, U.S. policy became much less accommodating. Roosevelt dismissed British Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s pleas to delay a massive Anglo-American amphibious invasion of northeast France and strong-armed Churchill into accepting a follow-on invasion of southern France. Roosevelt’s successor, Harry S. Truman, sharply restricted Lend-Lease aid to Britain and the Soviet Union immediately following Germany’s May 1945 surrender and then brought both states to the brink of economic collapse by abruptly terminating the program following Japan’s surrender three months later.

America’s increasingly high-handed behavior was fueled by its leaders’ growing confidence in the country’s preponderant power and their unwillingness to compromise on their all-embracing vision of postwar order. The former was evident in an intelligence analysis that made its way to Roosevelt in January 1943, which baldly proclaimed that the time had come to “start exercising the dominant influence which power properly entitles us.” The latter was evident in Roosevelt and Truman’s strident insistence on fulfilling Wilson’s earlier vision of a liberal international order. This generated frictions with Britain, which desperately sought to retain its still-extensive empire, as well as with the Soviet Union, which had no interest in democratization or capitalist multilateral agreements.

The Soviet Union During the Cold War

Although the United States and the Soviet Union were the only great powers to emerge from the rubble of World War II, the latter’s economy was devastated by the conflict, and it would not match the former’s military spending until the early 1960s. In October 1949, though, a still weakened Soviet Union received an enormous geopolitical boon when Mao Zedong’s communist insurgents emerged victorious in the Chinese civil war. This prompted Soviet leader Joseph Stalin to conclude a formal military alliance with the fledgling People’s Republic of China four months later. Following Stalin’s death in 1953, his successor Nikita Khrushchev dramatically increased Soviet military and economic assistance to China and even agreed to provide Mao’s regime with a prototype nuclear bomb.

By the end of the decade, however, as Soviet military power surged, Khrushchev increasingly viewed China as a needy “junior partner” whose leadership stubbornly refused to accept his reformist (i.e., anti-Stalinist) interpretation of Marxist doctrine. Even though China’s annual defense budget had grown to exceed that of any U.S. ally, Khrushchev took a series of steps that increasingly embittered Mao and ultimately fractured the alliance. Specifically, he hectored Mao to accept a “two China” solution to Beijing’s conflict with Taiwan, proposed that the Soviet Union operate a radio station and base its attack submarines on Chinese soil, reneged on his pledge to furnish China with nuclear weaponry, withdrew thousands of Soviet military and civilian advisors from China, and refused to support China in its low-level war against India. Bilateral relations continued to deteriorate precariously following Khrushchev’s replacement by Leonid Brezhnev in 1964, culminating in border skirmishes between the two communist states and China’s subsequent gravitation towards the United States.

Conclusion

As Germany, the United States, Japan, and the Soviet Union show, many rising great powers display an alliance allergy. These historical cases also suggest that China’s alliance allergy is likely to be enduring and unhelpful. It is likely to be enduring because all four rising great powers of the last century remained averse to alliances with powerful states even as they faced much stronger international systemic pressures embrace them than China faces today. It is also likely to be unhelpful as the same behavior contributed to the failure of Germany, Japan, and the Soviet Union to achieve their hegemonic ambitions.

Importantly, even if China reverses course by allying with Russia (as some analysts expect), historical precedent suggests that their partnership might prove fragile and ineffectual. A future Sino-Russian alliance would likely be as rickety as the Sino-Soviet alliance during the Cold War, albeit with the roles of rising power and powerful but undervalued ally reversed. And it would likewise remain vulnerable to U.S. diplomatic and economic “wedge strategies” aimed at its dissolution.

This does not mean that China alone can’t pose a challenge to Washington, just as Germany, Japan, and the Soviet Union did. Still, the good news for U.S. policymakers is that the American alliance network collectively holds an enduring power advantage over a virtually isolated People’s Republic of China. Recognizing this can help inoculate U.S. policy against threat inflation and avoid the much-discussed Thucydides trap.

Evan N. Resnick is a senior associate fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. His book Allies of Convenience: A Theory of Bargaining in U.S. Foreign Policy was published by Columbia University Press in 2019. He has also published articles in International Security, Security Studies, Journal of Strategic Studies, and European Journal of International Relations, among other outlets.

Hannah Elyse Sworn is a Ph.D. student in the Department of Political Science at The George Washington University. Her research interests include the politics of global economic regulation, intellectual property rights, the relationship between regulation and political legitimacy in authoritarian states, and how small states maneuver the regulatory preferences of great powers. She has also published an article on U.S.-Taiwan relations in International Affairs.

Image: The Kremlin