War and Adjustment: Military Campaigns and National Strategy

Rebecca Lissner, Wars of Revelation: The Transformative Effects of Military Intervention on Grand Strategy (New York: Oxford University Press, 2022)

The Anglo-Boer War between October 1899 and May 1902 was both embarrassing and transformative for the United Kingdom. Despite their eventual victory, British forces were initially surprised and even humiliated by the tactical success of the outmanned but skillful troops of the Boer republics. The Battle of Spion Kop in January 1900 marked one of the more shocking defeats early on. Winston Churchill, then 25 and serving as a war correspondent, wrote that “Men were staggering along alone, or supported by comrades, or crawling on hands and knees, or carried on stretchers. Corpses lay here and there. Many of the wounds were of a horrible nature.”

The effect of the war on domestic politics in Britain was notable. The historian AJP Taylor described it as bringing “first the culmination and then the end of an arrogant, boastful epoch, in which British public opinion seemed to have abandoned principles for power.” Comments by a prominent Liberal member of parliament attest to this judgment. Speaking from the opposition benches in 1900, William Vernon-Harcourt complained that the British government, on top of its mounting debt, was the “best hated people in the world.”

The embarrassing military campaign came at a time when the international order was changing. The economic and naval superiority that Britain had enjoyed for long stretches of the 19th century — which allowed it to maintain a policy of non-intervention on the continent — had been narrowing with the rise of ambitious powers like Germany, Russia, the United States, and France. Kaiser William II spoke in these years of Germany needing to obtain its own “place in the sun”, while U.S. President William McKinley had proclaimed in the aftermath of the Spanish-American War that America had “become a world power.” These factors, along with rising tensions with France and Spain, unsettled British leaders and the public. “The Empire,” wrote the British journalist W.T. Stead, had been “stripped of its armour, has its hands tied behind its back and its bare throat exposed to the keen knife of its bitterest enemies.”

Though an election in 1900 had returned the Conservative Party and its leader, Lord Salisbury, to Downing Street, there were great changes to come. Indeed, one of the great strategic shifts of British diplomatic history occurred in these years. The result, to varying degrees, of both the Boer War and the changing international landscape, the United Kingdom allied with Japan in 1902 (its first such agreement in over a century) and later reached an entente with France and a rapprochement with the United States. These actions clearly departed from the decades-long British policy of non-intervention and marked a grand strategic reset of the first order — one that firmly launched the United Kingdom away from a policy of non-intervention. The key architect of this policy, the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs Lord Lansdowne described it as such. “In these times no nation which intends to take its part in the affairs of the civilized world can venture to stand entirely alone.”

The effects of military campaigns on a nation’s grand strategy seem an obvious topic of importance for scholars. How can such moments of violence — when societies expend men and material and expose themselves and others to the most existential of risks—not mark dramatic moments of reflection on the purpose and direction of national strategy? Great strategic scholars from Michael Howard and Colin Gray to Lawrence Freedman and Hew Strachan have drawn these connections in their own work, especially as it relates to alterations after the termination of conflict. Yet fewer have examined the way in which information from the battlefield has, in real-time, shifted major strategic assessments on a national level. In her new book Wars of Revelation, Rebecca Lissner explores this connection in the American context by examining three of the country’s major conflicts in the 20th century — the Korean, Vietnam, and Persian Gulf wars — and their effects on American grand strategy. Rich in historical detail, the book uses these case studies to deliver a new theoretical framework for scholars of strategic studies, the “Informational Theory of Strategic Adjustment,” and even offers a persuasive contrast to some of the more established analyses of American foreign policy in the post-1945 period.

It is a welcome contribution from one of the rising, even leading, scholars in the field of security studies. A writer who has already helped us navigate the complex and sometimes frustrating topic of grand strategy, Lissner has also become one of the more respected voices on the future international order and American foreign policy. She has been a member of the Biden administration since its earliest days, having served as the deputy then acting director of strategy on the National Security Council staff and more recently as deputy national security advisor to the vice-president. It’s no stretch to assume, and perhaps hope, that many of her insights contained in this volume are considered during the ongoing official debates in Washington.

At the heart of the book is the relationship between grand strategy and the conduct of war, a connection with long historical roots. The concept of grand strategy itself originated in the early-19th century, used to describe the “grand” scale and size of the European armies during the French Revolutionary Wars. By the first decade of the 20th century, the term had expanded to include other aspects of foreign policy, including non-military instruments such as finance and trade. This fuller definition of the term was due in large part to the writings of British thinkers such as Alfred Thayer Mahan, Julian Corbett, and J.F.C. Fuller. Another was Basil Liddell Hart, who wrote in 1929 that “while the horizons of strategy is bounded by the war, grand strategy looks beyond the war to the subsequent peace.” In the period after World War II, this basic conception held. Michael Howard described grand strategy as not just “war fighting, but war avoidance,” which, throughout the Cold War, included nuclear deterrence.

It is worth noting that some writers such as Hew Strachan and Lukas Milevski have argued that the evolution of the concept of grand strategy — one that extends far from the anchor of violent conflict — has rendered the term meaningless. In his admirable book, Milevski argues the concept has become “standard-less” and “incoherent”, while Strachan argued years before that that it “no longer has coherence as an intellectual concept.”

While Lissner is not a part of this camp — early on she outlines her working conception of grand strategy as “the highest-order and most consequential dimension of statecraft” — she is clear that this particular study “uses the lens of military power, military threats, and military posture to illuminate how a state conceives of its role in the world.” This approach has traces of the understanding championed by the likes of Barry Posen, whose definition of grand strategy Lissner cites, and who for years has highlighted the links between military doctrine and grand strategic thinking. In many ways, this is a refreshing view given that students of grand strategy, myself included, tend to occupy themselves with other political, economic, social, and moral phenomena related to the practice of statecraft. Lissner, however, doesn’t mince words when she reminds us of what is arguably the most important dimension: “Wars are crucibles of grand strategy,” she insists.

On this basic judgment, Lissner profiles three of the most important military campaigns the United States has waged since World War II and assesses when and how grand strategic thinking changed among policymakers in Washington. The research is rigorous and is based on an impressive mix of primary and secondary sources. Some comments, even those seemingly made in passing, leave a mark. One example comes in her chapter covering the Vietnam War, where, before making her primary contribution, she reiterates that we can’t treat American grand strategy as somehow conceptually tidy between 1945 and 1991. There were, as she points out, key grand strategic adjustments in the 1960s and 1970s (among other periods) which had a great effect on the direction of national strategy. This subtle reminder, as much historical scholarship tends to do, bursts the illusion of simple narratives.

Moreover, the work is not intended to revise existing historiographies per se, but her findings have led her to arguments that certainly go against some existing historical accounts. Her analysis of grand strategic adjustments made during the Korean War seems to run up against earlier works by John Lewis Gaddis, Thomas Christensen, and Ronald Krebs. Concerning Gaddis in particular, where he sees alterations in grand strategy between the Truman and Eisenhower administrations, Lissner discerns more continuity across these periods, a result, she says, of initial strategic reassessments made by the Truman Administration during the Korean War. The case put forward here is sound, convincing, and worthy of being considered among these larger historiographical debates.

The stated contributions of the book, as she notes early on, is to first push back on an existing school of thought — one centered around the “null hypothesis”, which argues that there is no connection between military intervention and grand strategic change — and then to introduce her own theoretical framework. Central to her framework is a recognition that the “audit of battle,” a phrase she borrows from Kenneth Pollack, does in fact alter threat assessments and grand strategic assumptions and objectives. Specifically, it tends to alter a state’s understanding of its own military capabilities as well as that of its adversaries and allies — perceptions which, in turn, lead to adjustments in a state’s grand strategic outlook. Important here is a further qualification between grand strategic “adjustment” and “overhaul,” a distinction she described in a chapter for the recent Oxford Handbook of Grand Strategy. The latter term refers to a change in a state’s first level of grand strategy, something she describes as “a state’s orientation toward the international system,” whereas strategic adjustment refers to changes made in the second level of grand strategy. She defines this second tier as comprising “Subordinate levels of foreign policy behavior: assumptions about current and prospective threats and opportunities, and the availability and relative utility of the tools of national power.”

With its focus on the relationship between military operations and grand strategy, Lissner’s work exists at the intersection of military history, diplomatic history, and international relations theory. The first two of these scholastic disciplines — military and diplomatic history — have weathered an onslaught of perceived irrelevance in traditional history departments across the United States and Great Britain. This trend, especially given the current international context, is equal parts perplexing and frightening. Lissner’s book, however, is an ode to not just the relevance but the indispensability of these disciplines. In her study, she thoroughly mines the military and diplomatic history of her three main case studies and then, true to her background in political science, develops a theoretical framework to make sense of these observed tendencies. Theories and even theoretical frameworks tend to make historians, myself included, run for the hills; but Lissner’s points in this regard, both in this new book and her aforementioned chapter, are immensely practical. In future years, we might hope to see other scholars take this framework and apply it to other periods of conflict and diplomacy. For now, though, we can enjoy a work that is fascinating, stimulating, and belongs in the canon of the history and practice of American grand strategy.

Andrew Ehrhardt is an Ernest May Fellow in History & Policy at Harvard’s Kennedy School.

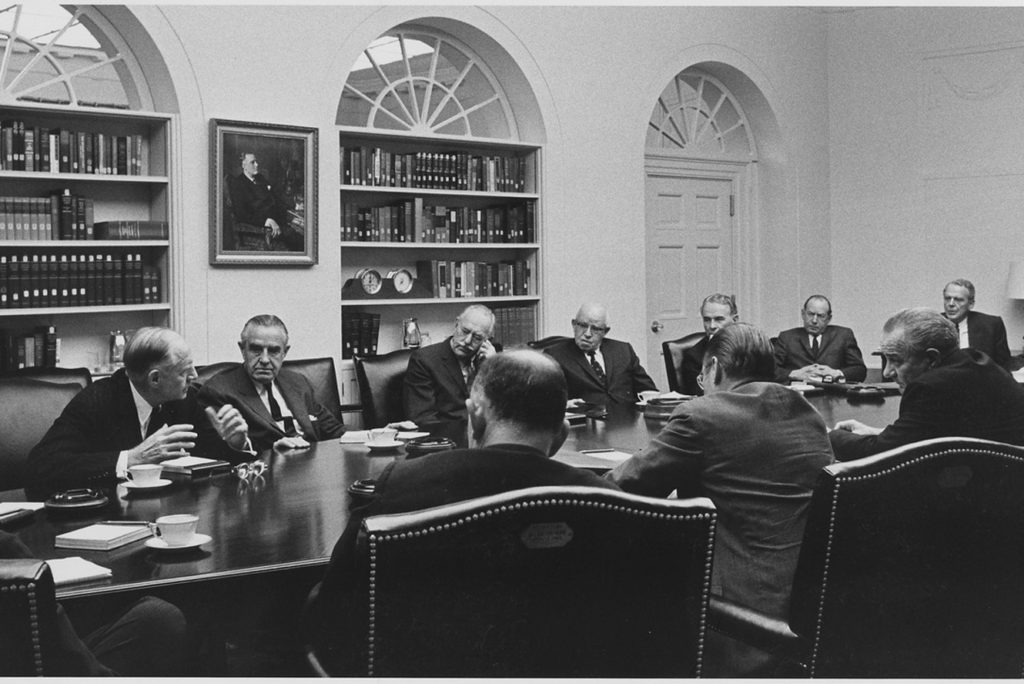

Image: National Archives and Records Administration