Intelligence and War: Does Secrecy Still Matter?

The secret services were remarkably conspicuous before the war in Ukraine. American and British agencies issued blunt assessments about Russian intentions and policymakers used intelligence to rally support against Russian aggression. They also released specific details about suspected efforts to manufacture a pretext for war, using intelligence as a “prebuttal” to phony Russian claims. Public intelligence continued after the war began, with daily summaries and high–profile appearances by spy chiefs, who seem to have embraced the spotlight and abandoned the tradition of working in the shadows. The secret world doesn’t seem so secret anymore.

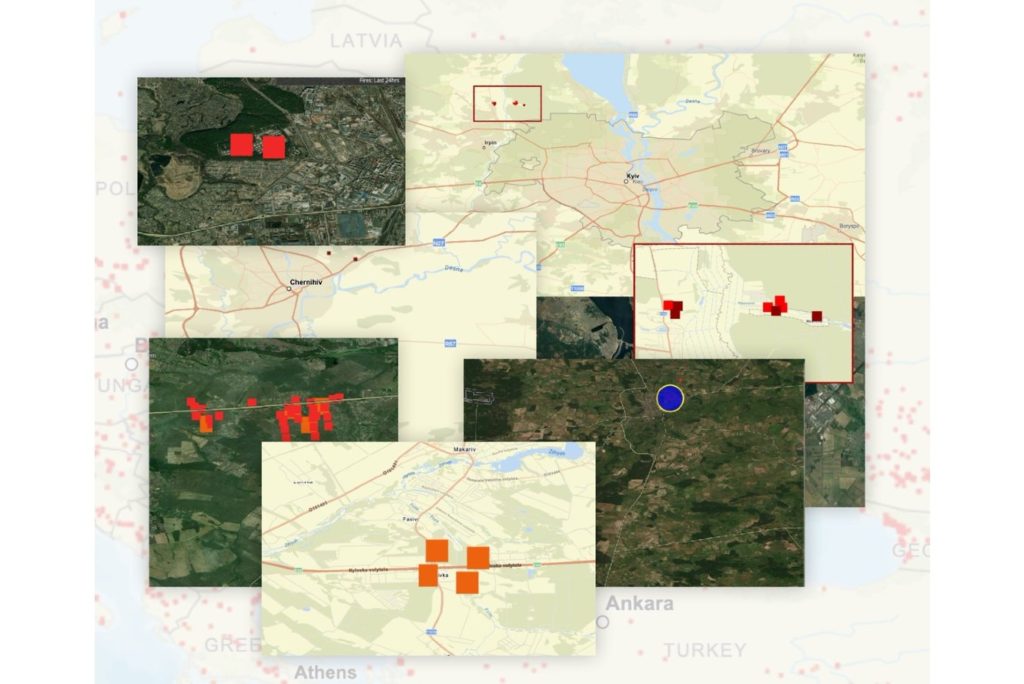

Open source intelligence has also played a large role in the public portrayal of the war, and in public debates about the best way forward. Commercial imagery provides regular views of the battlefield. Social media provides a platform for close-up views of military operations and wartime savagery. Open source analysts put these images and videos in context. A growing constellation of researchers from academia, think tanks, and private-sector intelligence firms offer detailed assessments of everything related to the war: tactics and strategy, resources and costs, adversaries and allies, winning and losing.

Most observers see value in these trends. They applaud leaders for making better use of public information, and for sharing their own secrets. The fact that intelligence agencies welcomed open sources into their assessments led to a clear victory before the war: Their warnings were right. The fact that policymakers used intelligence in public helped to build a strong and durable coalition against Russia. This was no small feat, given that some coalition members depend on Russian energy exports and therefore have a lot to lose. Intelligence sharing was essential to bringing them on board, and to keep them motivated.

The implications of the Ukraine experience seem clear. Public intelligence is an important tool in the hands of diplomats as well as generals. Intelligence works when intelligence agencies are open-minded about open sources. And there is no going back. Gone are the days when secrecy was the coin of the realm, and when a state’s possession of private information was the key to strategic success. “Historically, intelligence success often came in lockstep with secrecy,” a group of intelligence scholars recently wrote in these pages. “More than any other event in the last fifty years, the Russian invasion of Ukraine drives home the degree to which this is no longer true.” In a second article, the same authors argued that we are in the midst of a “global open source intelligence revolution.” Failure to embrace this revolution in the face of overwhelming evidence from the war risks poor performance from intelligence agencies before and during war. Stubbornly insisting on an outmoded version of spycraft, where secrets still reign supreme, risks disaster.

Perhaps. Technological advances have vastly increased the amount and quality of information available at our fingertips. Real-time data is abundant, making secrets seem unimportant and secrecy irrelevant. Yet there are reasons to believe that secrecy played an important role before and during Russia’s invasion of Ukraine — and that it might prove vital to ending the war.

Open Questions about Open Sources

Russia assembled a large invasion force over several months before the war began in February. Its military movements were not hidden, yet there was little agreement about what they meant. Some were sure a large invasion was coming, while others expected a limited incursion. Some thought the whole thing an effort to force Western concessions, not a prelude to war. After all, such a war would be costly and counterproductive to Russian security interests. Maybe President Vladimir Putin was simply stirring the pot, keeping his rivals on edge without paying a heavy price, and making them look absurd by overreacting.

U.S. allies were also divided. As the above-mentioned authors point out, some remained doubtful throughout the winter. While the Americans and British were openly predicting an invasion, French and German officials apparently thought that Russia would choose a different path. NATO intelligence briefings reportedly helped to change their minds, but not until the eve of the war. France’s Chief of the Defense Staff Thierry Burkhard offered telling comments in March. “The Americans said that the Russians were going to attack,” he said. “Our services thought rather that the conquest of Ukraine would have a monstrous cost and that the Russians had other options.”

None of these were foolish beliefs. It was reasonable to argue that Russia would show restraint before the war, given the enormous costs and risks. Yet it was also reasonable to infer that war was coming, given the scale of Russia’s mobilization and Putin’s neuralgia about Ukraine. The point is that freely available information did not point to a single obvious conclusion. Analysts made opposite but plausible inferences from the same data. The facts were not self-interpreting.

What, then, caused the skeptical European officials to change their minds about Russian plans? What intelligence information did NATO officials share internally? Given that the general outlines of Russia’s mobilization were already known, it seems likely that the intelligence provided more detailed and compelling insights about Russian plans. The fact that U.S. spokesmen had knowledge of possible Russian prevarications suggests that the intelligence community had unusually good access to Russian communications, and not all of this made its way into the public sphere. Some combination of human and technical sources may have provided a window into Putin’s plans in ways that were far beyond open source imagery.

The authors of the War on the Rocks articles correctly note that intelligence is only important if policymakers are willing to hear it. In this case American leaders proved receptive to warnings about Russian military action, but it is unclear that public intelligence was the reason why. President Joe Biden was already cynical about Russian intentions, after all, having declared Putin a “killer” a year before the war. At best, public intelligence reinforced these preexisting views. A better test will come when it cuts against policymakers’ beliefs and expectations, but that was not the case here.

The Roots of Russian Misfortune

Although the outcome of the war is uncertain, Russian forces have suffered grievously over the last three months. Ukraine has killed and wounded thousands of invaders, according to various estimates, and has taken a chunk out of Russian armor, airpower, and naval forces. Russia’s campaign against Kyiv failed spectacularly, despite what appeared to be overwhelming material advantages. It has since made grinding gains in the south and east, though again at substantial cost. None of this reflects the kind of limited conflict that the Kremlin implied when it announced its “special military operation” in February.

What explains this failure? It is too soon to tell, of course, given the limits of news reporting from Moscow. Yet there are signs that the war has been a massive Russian intelligence debacle. Russia based its actions on terribly misguided assumptions about Ukraine’s will to persist, its defensive capabilities, and the likely international response. It may be that Russian intelligence fed these beliefs and encouraged policymakers’ aggressiveness. Reports of an intelligence purge suggest that Russian leaders are at least disappointed in their performance.

The authors of the War on the Rocks articles correctly note that we are still in early days, and there is much we don’t know about Russian decision-making. Yet their preliminary verdict about Russian intelligence is damning: “Increasingly detached and dissociated from the global open source intelligence revolution, Russia mounted its attack on Ukraine entirely unprepared to fight a war in the 21st-century intelligence environment.” Innovative Ukrainian leaders went looking for new technologies that they could use to exploit open sources and gain the upper hand against their larger rival. Russian leaders, by contrast, clung to an outmoded model of intelligence. Had they been wise to information that was freely available, and invested in new ways of processing it, they would have been more careful in the early stages of the war. Perhaps they would have chosen not to invade at all.

All of this might be true. The problem, however, is that Russian failure had a lot more to do with Putin than with military organization and doctrine. An authoritarian strongman, Putin is very effective at ruling at home but very poor at wielding power abroad. It is likely that the same tools that he uses to stay in charge of Russia work against the quality of intelligence-policy relations. His regime brooks little dissent: Political opponents often end up in prison or dead. This does not create an environment conducive to a healthy exchange with intelligence officials. Rather than being the bearer of bad news, they have obvious incentives to sugar-coat their conclusions and provide intelligence to please. Putin’s public humiliation of his intelligence chief before the war reinforced the message.

Under these circumstances, it is hard to imagine what Russian intelligence might have done to change the outcome. Russia’s quagmire is a result of Putin’s obsession with Ukraine, his strategic ineptitude, and his ruthlessness. There is no reason to believe that he would have accepted a more sober and cautious estimate before the war, even if his intelligence officials had invested more in open sources or other novel approaches.

A more interesting question is whether Putin’s ham-fisted approach had trickle-down effects on tactical intelligence. In one sense, Russian military organization reflects Putin’s authoritarian instincts. “The directives of the commander are presumed correct,” the authors write, “and the staff only determine the specific tactics of how to execute the order.” This does not leave much room for deliberation and implies that intelligence reports are secondary at best. Everything depends on the commander’s judgment. Problems for intelligence likely intensify after operations commence, because their mission is to help the commander succeed rather than trying to make honest assessments about results. Here, intelligence officers may ignore or downplay open sources that carry bad news. A more fulsome tactical intelligence effort would be more open-minded.

Yet the same problem can befall intelligence officers who rely mostly on secret sources. In the Vietnam War, for instance, a controversy erupted in the secret world over the estimate of the size and resilience of insurgent forces. The U.S. military was attempting to win a war of attrition, and some officers were confident that they were killing enemy personnel faster than they could be replaced. CIA analysts, however, drew different conclusions from prisoner interrogations and captured documents. A struggle ensued among military and intelligence officials — ultimately the White House intervened and forced the CIA to back down. Policymakers preferred the military’s more optimistic estimate, which supported the public case for the administration’s strategy in Vietnam.

The problem for the CIA was not its choice of sources or analytic methods. The problem was the domestic politics of the Vietnam War, which made the Johnson administration wary of pessimistic assessments. We know much less about the current state of play in Moscow, but it is safe to assume that Putin was allergic to prewar assessments about the strength and resiliency of Ukraine’s fighting forces. The problem for Russian intelligence is not about grasping a technological revolution, but about whether domestic politics encourage productive intelligence-policy relations.

Secrecy and Strategy

There is no denying that public intelligence has shaped the debate over the war in Ukraine. Commercial imagery of the prewar Russian military buildup drew attention to the looming conflict. The flood of first-hand accounts on social media after the invasion painted Russian forces as simultaneously immoral and incompetent. This inspired sympathy for Ukraine as well as hopes that it could withstand the onslaught. Broad international support for Kyiv created pressure to deliver huge amounts of military equipment, and NATO members followed through, despite Ukraine’s position outside the alliance. The war seems a case study in how the new information environment is affecting international politics, and why secrecy is becoming relatively less important.

Yet it is too soon to make this conclusion. Evidence from the war suggests some familiar challenges for intelligence agencies, which have long sought to balance what they steal against what they can learn in the open. At its best, intelligence provides the “library function” for the state, as Richard Betts put it, by combining public and private information into useful forms for decision makers. The current task is how to cope with the increasing volume of information from a wider variety of sources. Ukrainian officials note that they are receiving thousands of reports about Russian troop movements from citizens via a government app. Such information, when combined with information from other sources, may allow Ukrainian forces to respond quickly. Yet organizational problems loom just beneath the surface. Judging the veracity of tactical reports from civilians with iPhones and getting them to the right units at the right time is a complex bureaucratic task. Open source information has been useful to commanders in past wars, but only because they learned to distribute it effectively.

A related problem is sheer information overload. Intelligence agencies relish detailed information on all things having to do with the enemy, and they may feel confident that their own information systems are capable of filtering out erroneous reports. Yet recent experience has shown that even highly sophisticated military services struggle to deal with vast amounts of data from various sources. They are impelled to collect more information to cut through ambiguity, and yet they end up “shifting the fog of war” to their own information systems. Military intelligence has always wrestled with the tradeoff between exhaustive collection and efficient use of information. Ukrainian officials are enthusiastic about their new collection methods. Whether they remain so depends on their ability to manage this tradeoff.

And there are other signs of continuity. In past wars secret intelligence-sharing proved important for bringing allies together against common enemies, and keeping them together in the aftermath. Secret intelligence likely helped to forge the coalition against Russia, providing details that overcame the skepticism of key allies. The U.S. intelligence community provided strategic warning of Russian intentions, tactical warnings about timing and location of the invasion, and indicated the ways in which Russia planned to justify the war. Sharing these secrets helped to lay the groundwork for a united response.

There are also indications that clandestine work remains essential in wartime. The Biden administration has increasingly shared intelligence that has helped Ukrainian forces to target Russian ground forces and warships. Some reports suggest that they are using intelligence to target Russian generals, though U.S. officials deny that claim. U.S. intelligence may have also helped Ukrainian forces to anticipate Russian military movements and assess Russian morale, though this is only speculation.

Finally, it is worth asking whether secret intelligence has aided Ukraine’s cyber defense. U.S. Cyber Command, for instance, supported Ukraine with “hunt forward” missions before the war. In such missions, foreign partners request U.S. assistance in strengthening their network defenses, and they also coordinate on improving intelligence on malicious cyberspace actors. The hope is that this will enable action against foreign threats as close as possible to their point of origin. Preempting cyberspace threats requires very good visibility into the murky world of foreign intelligence agencies and their non-state proxies. Open source analyses can be useful, especially when seeking to attribute cyberspace operations after the fact, but there is no substitute for clandestine collection if the goal is to stop them in advance. The effort to gain intelligence on Russia in cyberspace may be a reason why Russian cyberspace operations have been inconsequential.

Secret intelligence services may prove especially important in war termination. Domestic actors in Ukraine and the United States may be averse to a settlement that includes anything that looks like a concession to Russian interests. Yet unless Ukraine is committed to total victory, with Russian forces ejected from the whole country along with promises from Russia to permanently honor the pre-2014 borders, then some concession will be required. This will prove politically difficult for Ukrainian leaders who have rallied their country against Russian aggression, and for Biden, who called Putin a war criminal.

Intelligence agencies might prove useful in opening subterranean diplomatic channels, removed from the political fray. Quiet talks might help to determine when peace might be possible, and under what terms. Secret outreach is essential because these conversations are so politically sensitive, and because overt peacemaking is currently on ice. Intelligence officials will be well-positioned to facilitate the effort because they are in the business of secrecy.

Someday the war will be over — every war must end. Yet the peace will be tenuous because the conflict has deep roots. Ukrainians will worry that Russia seeks not a real peace but only a temporary pause to lick its wounds. For their part, Russians will worry that Ukraine is moving toward an ever-expanding NATO. Monitoring a fragile peace via intelligence will require clandestine collection and careful analysis. If the current conflict is a guide, open sources and public intelligence will be important, but they will not be enough.

Joshua Rovner is an associate professor in the School of International Service at American University.

Image: NASA fires mapping