The Light Fighter Is the Air Force’s Manned-Unmanned Team Solution

For an Air Force that wants to be ready to wage an effective air campaign against Russia or China without losing lots of expensive aircraft and pilots, manned-unmanned teaming offers an important avenue forward. The light fighter offers the most cost-effective way to develop tactics and build trust between unmanned systems and pilots while adding useful combat capability.

Developments in AI and teaming between autonomous drones and manned aircraft are driving a paradigm shift in air combat that the Air Force needs to embrace or risk irrelevance fighting against peer-level nations like China or Russia, who the Air Force is behind in this area. China has already made great strides in the development of competing drone technologies and low-tech solutions that favor quantity over quality. Both Russia and China have embraced manned-unmanned teaming as part of their strategic plan. Combined with the possibility of China invading Taiwan, rising tensions in Europe, and the ever-present threat posed from violent extremist organizations around the world, the Air Force should act fast.

Manned-unmanned teaming is the future of air combat and recent exercises and demonstrations have shown it being critical to enabling increased combat effects while minimizing risks to pilots. Under the Skyborg program, Boeing’s MQ-25 and ATS, Kratos’s Valkyrie XQ-58A and UTAP-22 Mako, General Atomics’ MQ-20 Avenger, and the two new drones that were recently announced are all being developed as autonomous drones for the teaming role. Aircraft in the teaming role will have to be fast enough to keep up with fifth- and sixth-generation fighters, have the advanced sensors and communication systems to fuse targetable data from multiple sources and be capable of carrying extra weapons.

However, the key is to get a manned aircraft capable of effectively controlling these assets. That’s what the Air Force is lacking. The light fighter is the answer to all these challenges. To understand how, let’s explore what these fighters are and why they would be so useful for training, peer conflict, special operations, and helping with pilot shortfalls.

What Is a Light-Fighter Aircraft?

It’s easy to confuse this term with others, such as light attack and light combat aircraft. Indeed, all refer to aircraft that benefit from being smaller, more cost-efficient, and easier to produce than current fourth- and fifth-generation fighter fleets. For our purposes, the main distinction is that a light fighter is turbine powered, whereas light attack is propeller driven.

The concept of using a light fighter to fill critical gaps in combat capability is not a new one. During the Vietnam War, the Air Force requested 200 F-5C Skoshi Tiger aircraft under the Sparrow Hawk program as a response to heavier than expected attrition of fighter aircraft, primarily because they were relatively inexpensive and quick to produce. While originally the Air Force did not consider the need for light-fighter aircraft, the F-5C was exceptionally capable in the Vietnam conflict and was proven to be less vulnerable to enemy fire due to its size and maneuverability.

Light combat aircraft have been championed by many organizations for years as the best solution for close air support and combat search and rescue missions in remote or uncontested theaters. The program saw new life a few years ago when the Air Force decided to have a competition and was mostly comprised of small, lightweight propeller-driven aircraft. Several articles have been published in War on the Rocks and other outlets on the light-attack concept, notably by Col. (ret.) Mike “Starbaby” Pietrucha, a leading advocate of the program inside and outside of the Pentagon. The authors discuss the platform’s usefulness in asymmetric conflict, dispelling myths about the platform, and how the Air Force has recently shifted the focus of the program towards foreign internal defense after the results from the light attack experiment.

One of the biggest issues with light-attack propeller aircraft, and the reason the Air Force has likely lost interest, is because they are slower and less survivable than turbine-powered aircraft. This means it is harder for them to survive advanced ground or air threats and keep pace with the aircraft that could protect them.

By contrast, light-fighter aircraft are turbine powered, giving them the speed and maneuverability advantage over most light-attack propeller aircraft. Speed allows these aircraft to keep pace with the Air Force’s current fighter inventory and loyal wingman drones, allowing them to survive the skies above contested territories. Turbine-powered aircraft also enable reduced response times and larger payloads of specialized systems and munitions.

Light-fighter aircraft are perfect for the manned-unnamed teaming role. However, current light-fighter aircraft — such as the Korean F-50, Tejas, M-346, and L-159 — are not teaming-capable with unmanned aircraft nor do they have the open architecture components needed to integrate advanced systems without substantial modification and cost. Future light-fighter craft need to be designed with this in mind.

A new revolution in aircraft digital design and a need to replace the ageing T-38 has led to development of an advanced jet trainer aircraft such as the Boeing T-7, which the Air Force has already purchased. However, these aircraft are primarily trainers, and do not have the required components such as hardpoints or classification requirements to easily convert to a fighter aircraft.

This is why Air Combat Command requested bids from industry for an advanced “tactical” trainer aircraft under the “Rebuilding the Forge” concept. Pietrucha and Jeremy Renken’s 2019 article offered an excellent comparison of proposed light-fighter aircraft capabilities using variants of advanced tactical trainer aircraft. Albeit with slightly less range and payload capacity, a light fighter can do the same tasks as traditional fourth-generation fighters like the F-16 or A-10, including the ability to carry assortments of bombs, missiles, and specialized payloads; to air-refuel; to dogfight; and to perform the same close air support, interdiction, and combat search and rescue missions.

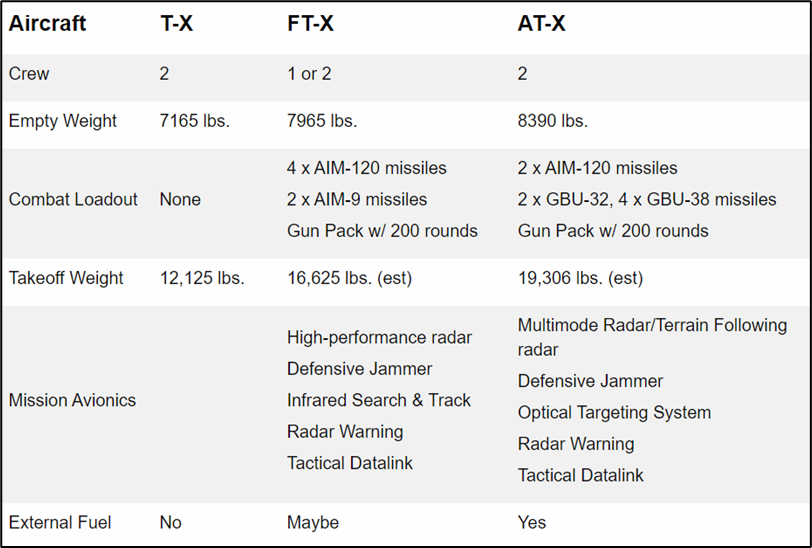

Table 1: Notional T-X, FT-X, and AT-X Hypothetical Loadouts

This table breaks out differences between an attack variant and fighter variant of advanced trainer aircraft. (Image credit: Mike Pietrucha and Jeremy Renken)

The advanced tactical trainers are the perfect asset for training pilots in manned-unmanned teaming. These aircraft, such as the Boeing T-7 or Aeralis trainer, utilize new digital design technology, simplified maintenance, and open architecture systems (which allow for integrating multiple communication mediums and are necessary for manned-unmanned teaming) that are necessary to serve as a cost-effective base for a teaming-capable light-fighter aircraft. While the advanced tactical trainer is mainly being considered for training future fighter pilots, it is a small jump for the Air Force to also purchase fighter variants.

Teaming-capable light-fighter aircraft derived from advanced tactical trainers would be able to not only perform the roles of traditional fighter aircraft, but also develop and implement future air combat teaming capabilities. They can do this for far less money and more efficiently than fifth-generation aircraft and bridge the gap until fifth- and sixth-generation manned-unmanned teaming becomes combat ready.

The Air Force Needs It

There are three key areas in which a teaming-capable light fighter can benefit the Air Force: training, peer-level conflict, and special operations.

From a training aspect, one of the key pieces to keeping fighter pilots proficient in air combat is the ability to exercise their skills against real aircraft acting in a “red air” (aggressor or adversary) capacity. The problem, however, is that, again due to the reductions in legacy fighter platforms, the Air Force has had to contract out red air to private companies at a cost of $7.5 billion. Contract red air is incredibly expensive, and this contract only provides capability for six bases. Bases that do not have access to contract red air are responsible for generating their own aircraft for this purpose, which can reduce training benefits and add costs.

With the looming risks of peer-level conflict, the Air Force more than ever needs additional red-air capability. This is why the Air Force is investing heavily in teaming capabilities, specifically fifth- and sixth-generation aircraft like the F-35, B-21, and Next Generation Air Dominance fighter. However, one of the issues with effectively employing manned aircraft with autonomous teammates in a combat scenario is trust. This is why the Air Force recently placed an order for Blue Force Technologies’ “Fury” drone to use as red-air aggressors. If the pilots of fifth-generation fighters get to fight against autonomous drones, eventually they will be comfortable with them as “blue air” wingman.

However, getting single-seat F-35 pilots to want to fly with and rely on autonomous loyal wingman in combat will likely be many years away. And at about $30,000 per flight hour for the F-35, it will be a very expensive training bill to pay. Combine this with the fact that the Air Force is reducing the amount of fighter aircraft in the inventory under the 4+1 model and that fifth-generation aircraft are not being produced fast enough to outpace these reductions, and there is a gap in having an affordable solution to developing this technology fast enough to outpace peer-nation competitors. Light-fighter aircraft are one the most cost-effective solutions that can fill Air Force critical capability gaps and accelerate manned-unmanned teaming trust and capabilities while the production of next-generation fighters catches up.

A teaming-capable light fighter is the optimal aircraft to team with red-air drones to provide red air for relatively little cost and train new fighter pilots from the start in the manned-unmanned teaming role. Two birds with one light-fighter stone. This builds trust and confidence in autonomous systems while providing the much-needed red-air support for fifth- and eventually sixth-generation aircraft in realistic scenarios for peer-level conflicts. The teaming-capable light-fighter aircraft does not have to be relegated to training though, as it does have game in both peer-adversary and low-intensity conflict fights.

Outside of the training realm, teaming-capable light fighters have applications against peer-level adversaries. The light fighter is not practical for taking down integrated air defenses because it is not stealthy and does not have long enough range to be effective. However, in areas of established air superiority the light fighter can be very useful. It is not the ability to drop bombs or shoot missiles that makes the light fighter valuable, it is the ability to control other aircraft who can. Especially against a peer adversary, success will come from the ability to act as a sensor integrator to share command-and-control data and information, which was expertly discussed in a previous War on the Rocks article about the future of air superiority.

In the peer-adversary fight, a light fighter may not even need to carry munitions at all nor even be considered a strike aircraft. Instead, they would carry extra gas to stay on station longer, electronic attack equipment to increase survivability and provide certain battlefield effects (e.g., jamming), and carry systems that can control autonomous aircraft (i.e., teaming). It is the autonomous aircraft that would be equipped with the specialized systems and munitions that would be coordinated from the light fighter to execute reconnaissance, strikes on enemy targets, or provide support for other strike packages and assets.

This is much more in line with the tactical air coordinator role. The light fighter can sort, task, and track scores of unmanned assets all while staying safely outside of enemy threats. For example, while the fourth- and fifth-generation fighters are busy engaging air or ground targets, the light fighter can be assigning, tasking, and coordinating drone strike packages for a given area of operations. This ensures different fighter groups never run out of missiles and also ensures they never run out of gas since they can also assign drone tankers, like the MQ-25. This all can happen while minimizing the number of humans who are at risk.

While the Air Force has shifted focus toward competing against peer adversaries, there still exists the need to counter violent extremist organizations and support worldwide special operations in low-intensity conflict theaters, such as the current air campaign in Syria. While manned fifth-generation aircraft like the F-35A will be utilized for the foreseeable future to support special operations in contested theaters, they are essentially impractical for low-intensity conflict due to their high cost per flight hour and robust maintenance requirements. You don’t need advanced stealth aircraft to follow a pickup truck for hours in the middle of Africa. Plus, training fighter pilots in these missions takes focus away from training for conflict with a great power.

This is one of the main reasons Air Force Special Operations Command is pursuing an “Armed Overwatch” platform that can provide intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance as well as a limited strike capability for remote special operations forces.

Leveraging the light fighter’s smaller maintenance and support footprint combined with a turbojet’s high speed will allow for rapid additional support to Armed Overwatch or AC-130 Gunship platforms on critical missions such as the hostage rescues in Syria 2014 and Somalia 2012. Missions like those conducted by special operations forces in low-intensity theaters have traditionally been supported by fourth-generation fighter aircraft. However, with reduction in fourth-generation fighter platforms, a teaming-capable light-fighter aircraft would be a perfect asset to provide tactical air coordination and critical close air support for less cost and without taking valuable training time away fourth- or fifth-generation fighters. Light fighters can fill a critical capability for a fraction of the cost.

Back in 2015, I was the tactical air coordinator on a U-28A — a manned tactical intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance aircraft — for the largest direct action special operation in Afghanistan since Operation Anaconda. The operation involved four special operations teams assaulting an al-Qaeda training camp spread out over 30 square miles over a three-day period. During this operation, my crew and I coordinated and deconflicted dozens of airstrikes for over 20 combat aircraft comprised of AC-130s, F-16s, MQ-9s, and other manned reconnaissance and electronic warfare aircraft. My crew of four was responsible for communicating over nine different radio nets between air, ground, and command and control entities. The operation decimated al-Qaeda and resulted in a record-breaking collection of enemy data. The operation was so successful due to a centralized node that was able to find and pass targets to multiple shooters. However, it was a nightmare to coordinate.

The ability to control drones from the cockpit would have allowed for seamless target data sharing and correlation, weapon to target matching, and assigning, deconflicting, and attacking targets. This could all be done without having to waste time coordinating over radio nets and greatly reduces the risk of air-to-air collisions with other planes or weapons in flight.

The best aircraft to perform the tactical air coordinator role specific to special operations is the aircraft with the most situational awareness. The U-28A was great at the tactical air coordinator role over traditional fourth- and fifth-generation aircraft because it had a longer loiter time and more sensors than a typical two-ship flight. However, advanced light fighters could use loyal wingman drones to park over a target almost indefinitely, while the light fighter itself swaps out. The key here is the seamless data integration only made possible by the manned-unmanned teaming, which is why future special operations missions would benefit greatly from advanced light fighters as they reduce communication friction and allow for more rapid passing of data.

Who Would Fly It?

The Air Force is short 2,000 pilots to fill the existing aircraft that it has. Conveniently (albeit not for remote pilots), looming automation from AI combined with multi-mission control (the ability to control multiple remotely piloted aircraft with a single operator) will likely reduce the requirements for remote pilot manning. Since remote pilots have the battlespace awareness, complex decision-making, and combat knowledge from decades of combat operations combined with a deep knowledge of how unmanned systems operate, they are ideal candidates to fly the light fighter.

As Mike Byrnes noted in these pages, remotely piloted aircrew are now the largest community of Air Force pilots. He also highlighted a study that proved no discernable cognitive differences between remote pilots and manned pilots. The largest factor preventing the Air Force from using remote pilots to reduce the fighter pilot manning deficit is a cultural one.

To go one step further, the Air Force should base the light fighter at remote pilot bases that have drones like the MQ-9 Reaper. Most of these bases, especially in the Air National Guard, have runways and facilities from previous aircraft that sit mostly empty and with minimal cost could be converted to support advanced light-fighter aircraft. Since teaming-capable light fighters are based off advanced tactical trainers — whose job it is to train fighter pilots — having them co-located at MQ-9 bases would allow for seamless conversions. Simply walk across the street and start training directly in the light fighter. This results in a significant increase in available fighter pilots with minimal cost and is one of the few ways the Air Force could dig itself out of the pilot shortfall.

“Accelerate Change or Lose”

The Air Force needs to act fast to counter Chinese capabilities but still provide critical and cost-effective air support for counter extremist operations. The teaming-capable light fighter is the key to doing both. The light fighter will free up resources and training burdens for fifth-generation fighters while also building trust and confidence with autonomous loyal wingman aircraft.

This is enabled by embracing autonomous aircraft and taking advantage of the untapped pilot resources the remote piloted aircraft community has to offer. If implemented correctly, the teaming-capable light fighter will usher in manned-unmanned teaming, revolutionizing air combat and sending a deterrent signal to China and other adversaries. This is how you accelerate change.

Maj. Alex Biegalski is a pilot with the Syracuse Air National Guard and a former U-28A Draco pilot. He has amassed over 2,000 combat hours supporting special operations around the world and defined the tactical air coordinator role for special operations. He currently aiding the development of AI systems and skyborg programs with the Air Force Research Lab and is a member of an action group defining light fighter capability requirements.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Air Force or the U.S. government.

Image: U.S. Space Force (Photo by Airman First Class Thomas Sjoberg)