‘A well-regulated Militia’: The Laws that Can Counter Domestic Terrorism

Timebombs are ticking all across the United States, and no one seems inclined to do anything about it. Private armies, who call themselves “militia groups,” routinely stockpile firearms, conduct training in combat tactics, and engage in military drills. According to the U.S. intelligence community, these paramilitary organizations now pose the greatest domestic terrorism threat to the U.S. government. Yet, American authorities have largely allowed this conduct to occur undeterred. The time has come to defuse these bombs.

In June 2021, the Biden administration issued the nation’s first-ever National Strategy For Countering Domestic Terrorism. The strategy makes some important recommendations, but one additional step that seems urgently needed is a plan to address the threat posed by militia violent extremists. These are members of private paramilitary organizations that have no legal authority. In recent years, private militias have become more visible and more bold. Social media and access to powerful weapons have enabled these groups to join forces to create a deadly risk to America’s government and public safety. To reduce the threat of domestic terrorism by militia violent extremists, two important measures are needed: first, enforce existing state laws that limit militia activity; and second, enact new federal legislation to permit federal law enforcement to neutralize this grave threat.

The State of the Threat

The Southern Poverty Law Center assesses that there are 169 private paramilitary groups operating in the United States. Used correctly, the term “militia” refers only to residents who may be called up by the government to defend the United States or an individual state. Private groups that call themselves militias, however, operate without any government authority. They have appropriated a term that invokes the revolutionary origins of America and the heroics of citizen soldiers to falsely legitimize their existence. According to the Institute for Constitutional Advocacy and Protection at Georgetown University Law Center, all 50 states prohibit private, unauthorized groups from engaging in activities reserved for the state militia, including law enforcement activities. Private paramilitary groups do not defend their country in the manner of a national guard — and the ones operating in the United States do not — but instead act as vigilantes against government officials to achieve their favored political ends. According to the Anti-Defamation League, the militia movement grew in the United States following the election of President Barack Obama and the 2008 financial crisis. Examples include the “Three Percenters,” who emerged in 2008, proclaiming themselves “patriots” who protect Americans from government tyranny, and the “Oath Keepers,” founded in 2009, who recruit former members of law enforcement and the military to build a network of state militias.

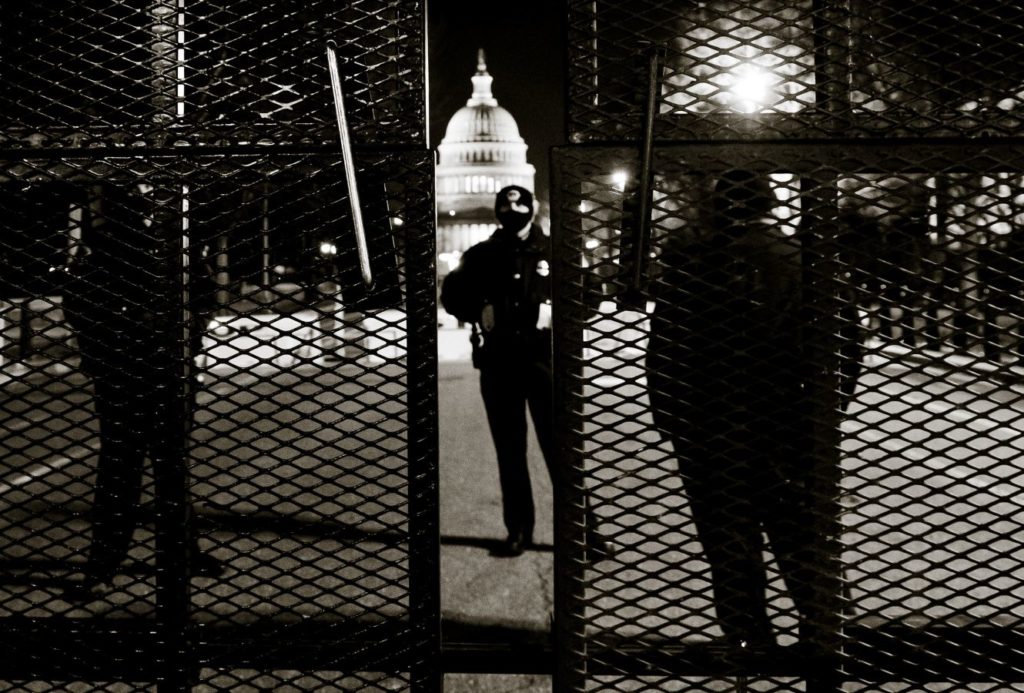

In recent years, individuals affiliated with paramilitary organizations have been charged with violent crimes. Some of the defendants involved in the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol were members of private paramilitary groups. Most notably, members of the Oath Keepers were charged in January 2022 with seditious conspiracy and other offenses for agreeing to forcefully oppose the lawful transfer of presidential power. In 2020, the Department of Justice charged members of a private militia group, who call themselves the “Wolverine Watchmen,” with conspiring to kidnap and kill Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer over her executive orders on COVID-19 policy. Heavily armed paramilitary groups contributed to the violence at the 2017 “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, and created confusion for law enforcement by making it difficult to know whether armed individuals wearing combat boots and tactical gear were sworn officers or protestors.

Social media makes it easy for violent extremists from around the United States to communicate with each other to plan attacks against government authority. Easy access to assault rifles and other weapons of war makes the threat potential deadly.

The State of the Law

All 50 states have laws that prohibit private militia activity. In 29 states, laws prohibit private military groups from organizing without authorization from the state government. These statutes often specifically prohibit the “parading” or “drilling” in public with firearms. In 25 states, anti-paramilitary activity laws bar teaching, demonstrating, instructing, training, and practicing in the use of firearms or explosives. Laws in 17 states prohibit falsely assuming the duties of law enforcement by engaging in the functions of police officers, or wearing uniforms of the U.S. military or close imitations.

For example, in Nevada, where the Oath Keepers were founded, state law prohibits “any body of individuals other than municipal police, university or public school cadets or companies, militia of the State or troops of the United States, to associate themselves together as a military company with arms without the consent of the Governor.”

These laws are consistent with a longstanding Supreme Court precedent that states may prohibit individuals from associating together “as military organizations, or to drill or parade with arms in cities and towns unless authorized by law.” While the First Amendment right to free association permits like-minded individuals to gather to express ideas, states may ban paramilitary conduct. Likewise, the Second Amendment offers no safe harbor, referring to “a well regulated Militia,” which has been traditionally limited to official national guard units subject to the oversight of public officials.

Despite the growing threat posed by private militia groups, their illegal activity is rarely prosecuted. Private militias in some regions have become so commonplace that their activity is accepted as normal. The National Police Foundation has warned that these groups sometimes align with local police departments or sheriff’s offices, dangerously blurring the lines between authorized law enforcement and private citizens. Some groups, such as the Oath Keepers, actively recruit former police officers and members of the military. The Brennan Center for Justice has documented links between law enforcement and “far-right militant groups” in 14 states. In Michigan, an elected sheriff appeared onstage at a 2020 rally opposing COVID-19 shutdown orders alongside a militia member who was later charged, along with other militia members, with conspiracy to commit kidnapping the governor and other crimes. The sheriff publicly defended them, suggesting that their conduct was perhaps an attempt to carry out a lawful citizen’s arrest. It has been suggested by a national security expert that one reason these anti-militia laws are not enforced is that prosecutors are unaware that they are on the books. The National Police Foundation’s research suggests another possible explanation for a lack of law enforcement action against paramilitary groups in some instances, noting that some officers even “engage with [militia members] in a way that gives an appearance of mutual support.”

The Proposal

An effective strategy to counter domestic terrorism should include enforcing existing laws that regulate paramilitary activity conducted by private militia groups, as well as enacting new federal legislation. Vigorous enforcement of state laws would disrupt existing groups and deter individuals from engaging in prohibited paramilitary activity. But the inconsistent patchwork of state laws alone is not enough in a society with easy interstate communication and travel. In addition to enforcing state laws that are already on the books, Congress should consider federal legislation to address unauthorized paramilitary activity.

One proposal to strengthen the U.S. government’s ability to counter violent militia extremism has been offered by Prof. Mary McCord at Georgetown University Law School. McCord is the former acting assistant attorney general for the National Security Division at the U.S. Department of Justice. In congressional testimony about the Jan. 6 attack, McCord outlined a proposal that would permit civil injunctive relief (i.e. permitting the government to file a civil lawsuit against militia members) and asset forfeiture for paramilitary militia activity. Prohibited conduct could be similar to state laws that ban private groups from drilling or parading with firearms in public, falsely assuming the duties of law enforcement by engaging in the functions of police officers, or wearing uniforms of the U.S. military or close imitations. Faced with a preponderance of evidence against individuals engaged in such prohibited activity, a judge could enter an order prohibiting them from continuing to engage in this conduct. Forfeiture laws permit the government to seize assets that are used as instrumentalities of illegal activity. In the case of illegal militia activity, this could be weapons, tactical gear, and uniforms.

In addition to permitting the government to seek civil relief, McCord’s proposed federal legislation would include a criminal provision that would prohibit persons, while armed, from: publicly patrolling, drilling, or engaging in paramilitary techniques; asserting authority over others without legal right; intimidating others in the exercise of their constitutional rights; or training for any of these acts. Such laws would enable law enforcement to disrupt militia violent extremists without waiting for them to carry out a deadly attack.

State law enforcement can most certainly bring charges for violent crimes, but they are less equipped than their federal counterparts to prevent attacks. State agencies often lack the resources and authorized investigative techniques to undertake the kind of long-term efforts needed to dismantle criminal organizations. In addition, with advancements in technology, militia activity is no longer confined inside state lines. Federal law enforcement, in contrast, is well-equipped to conduct the types of proactive investigations that would be necessary to disrupt militia groups before they attack. The same techniques that federal law enforcement has used for decades against the Mafia and international terrorist organizations would be available: wiretap orders, undercover agents, informants, and the grand jury process to question reluctant or fearful witnesses. With a statute to authorize the opening of an investigation, federal agents could work to neutralize the threat of private militia groups without having to wait for an attack to occur. And, importantly, their investigative and charging authorities extend to anywhere in the United States.

Constitutional Considerations and Political Obstacles

A number of reasons explain why militia groups have been permitted to exist and grow unimpeded. One is the concern that overreach by law enforcement could infringe upon civil rights and civil liberties. America has previously seen civil liberties abused in the name of protecting security, from the internment of Japanese-American citizens during World War II, to the FBI’s abuse of its authority to disrupt political movements in the 1960s and 1970s. For example, congressional investigations found that the civil rights movement and Vietnam War protests during the 1960s were targets of government abuse: The Church Committee, named for U.S. Senator Frank Church, found that, in the name of protecting national security, the FBI had harassed civil rights and anti-war activists and spread disinformation about them to disrupt their activities and smear their reputations.

Laws governing domestic terrorism present unique legal concerns. For example, federalism raises questions about the extent to which Congress can outlaw acts of domestic terrorism or whether that belongs in the exclusive domain of the states. But this concern should not affect the enforcement of state laws, and with sufficient factual findings by Congress, federal legislation could be enacted within Congress’s express or implied powers under the Constitution. For example, findings of interstate communication between militia members, or transport of weapons across state lines, would provide sufficient bases for congressional action under the Commerce Clause. Indeed, the recent indictment against the Oath Keepers alleged that the group used messaging applications and transported weapons across state lines in their preparations to attack the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6 and their subsequent planning to obstruct the lawful transfer of presidential power.

The First Amendment right to free speech is also a potential concern. You couldn’t charge someone with a crime for making a general statement of an intention or desire to “fight” the government for their rights, for example; the charges would not withstand judicial scrutiny. Divining exactly where the line falls between illegal conduct and constitutionally protected speech is not an exact science, but legislation focused on conduct, as opposed to ideas, is permissible. For example, existing federal statutes prohibit inciting violence, threatening to kill others, and communicating to mobilize violent plots. These statutes tend to be interpreted narrowly so as to protect constitutional rights. Similarly, statutory language addressing militia violent extremists would need to be appropriately cabined to prevent abuse of the law to attack political movements — no small task.

The First Amendment right to free association is also implicated in domestic terrorism cases. Though it is not textually articulated in the First Amendment, the Supreme Court has recognized “a corresponding right to associate with others in pursuit of a wide variety of political, social, economic, education, religious, and cultural ends.” This implied right to free association makes it difficult to disrupt private militia groups or protests that pose threats of violence, such as the “Unite the Right” rally that took place in Charlottesville in 2017. A federal statute could not prohibit groups from gathering, but it could prohibit them from engaging in certain conduct, such as military drilling or parading with firearms.

Another potential obstacle to a federal statute addressing militia violent extremism is the Second Amendment, though the actual legal impediment the Second Amendment presents is overblown. Gun enthusiasts and lobbyists who take an absolutist view of the Second Amendment may object to any new law that regulates the use of firearms, despite the Supreme Court’s language in District of Columbia v. Heller that “the right secured by the Second Amendment is not unlimited,” and is “not a right to keep and carry any weapon whatsoever in any manner whatsoever and for whatever purpose.” For example, Congress prohibits the possession of firearms in furtherance of violent crimes and drug trafficking offenses. Likewise, it could prohibit the unauthorized use and carrying of firearms by civilians while parading or drilling in military tactics.

Opponents may argue that the Second Amendment protects militia activity itself because of its language regarding “a well regulated Militia.” Yet, the Second Amendment offers no refuge to groups that are privately organized and accountable to — regulated by — no one. As noted by McCord, “regulated” means regulated by the government. In the United States, militia refers to official national guard units subject to the oversight of public officials. Since 1886, the Supreme Court has held that the government may prohibit personal military groups as “necessary to the public peace, safety, and good order.”

The Fourth Amendment’s guarantee against unreasonable searches and seizures is also implicated whenever law enforcement is called upon to conduct investigations. For foreign intelligence collection, a court has recognized a special-needs exception to the warrant requirement when investigations are directed at foreign powers reasonably believed to be located outside the United States. Since domestic terrorism cases do not qualify for that exception, investigations would be subject to the same safeguards and judicial oversight that are used in all other criminal cases. New federal laws would permit the FBI to use sensitive investigative techniques, such as wiretaps, cell site location information, informants, undercover agents, and sting operations. But the targets of these domestic terrorism investigations would still receive more protection than those provided to targets of international terrorism investigations.

In addition to civil liberties concerns, another obstacle to addressing militia violent extremists is political will. Politicians may tend to shy away from new laws that will be controversial and will attract opposition from the gun lobby and the far-right. In addition, a new law that seeks to disarm militia groups is the very doomsday scenario for which some groups claim they have been preparing. According to a report issued by the Anti-Defamation League, “The combination of anger at the government, fear of gun confiscation and susceptibility to elaborate conspiracy theories is what formed the core of the militia movement’s ideology.”

The Charge

Legal efforts to deter private militia activity could trigger a violent response. And yet, we cannot let fear of opposition prevent those charged with protecting national security and public safety from taking the steps necessary to do so. Militia violent extremists pose an urgent threat to the U.S. government and its citizenry. They have already used force to disrupt the peaceful transfer of power on Jan. 6 and conspired to kidnap Michigan’s governor, according to filed indictments. Furthermore, private militia members contributed to violence at the 2017 “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville. Two measures can help to reverse this trend. First, state prosecutors should immediately begin enforcing laws already in place. Second, Congress should pass federal legislation to give federal law enforcement the tools it needs to prevent these groups from preparing for attacks through civil injunctions, asset forfeiture, and criminal prosecution.

Without intervention, we can expect more violence to come.

Barbara McQuade is a professor from practice at the University of Michigan Law School. She served as United States Attorney for the Eastern District of Michigan from 2010 to 2017, and as co-chair of the national interagency Domestic Terrorism Executive Committee from 2015 to 2017.

Photo by Victoria Pickering