The Empire of the Anti-Imperialist: Dealing with Nicaragua’s Ortega

In his dotage as a globe-trotting interviewer, the late David Frost traveled to Nicaragua in 2009 with the aim of prising some truths out of its president. He asked the country’s leader Daniel Ortega, who had returned to power two years earlier, about the allegations of corruption, election fraud, and authoritarianism stacking up against him, and wondered whether the president might wish to rule forever. Swatting aside the criticism as the invention of “restless” intellectuals, Ortega noted that his mother had lived to 97, and as such he’d welcome any chance to contribute more to “the development of the revolution. … These are very exciting times.”

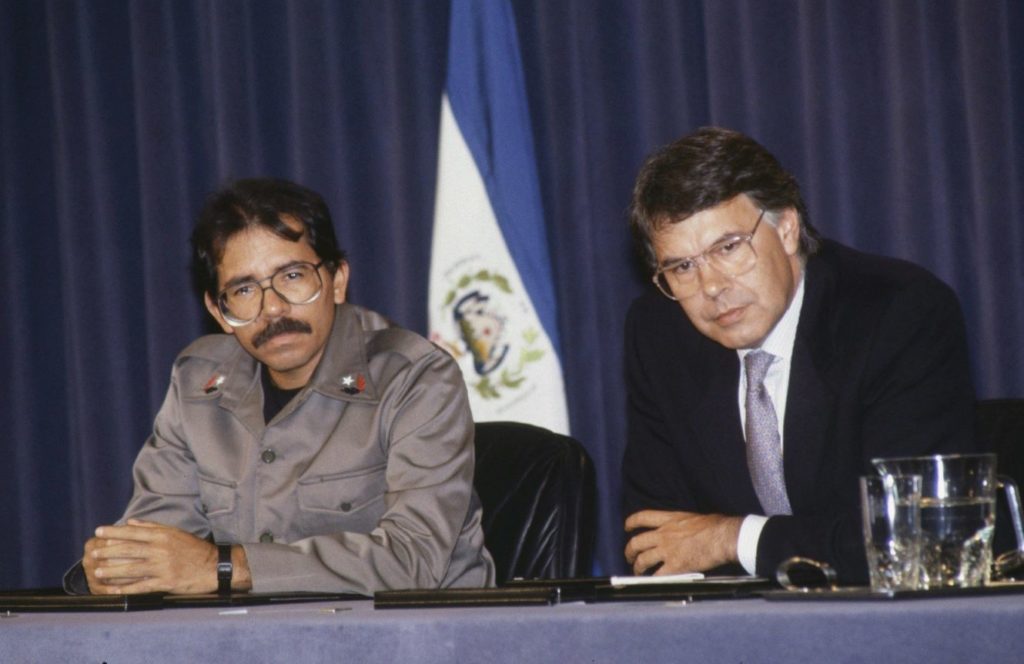

Ortega’s opponents, whether in jail in Nicaragua, in hiding, or exiled abroad, would ask drily what revolution that might be, and whose excitement. The Nicaraguan president, now in the 15th year of his second run as president (he also headed the government a few years after the Sandinista guerrillas toppled the Somoza dictatorship in 1979), has over recent months led the most serious violation of political rights and coercion of critical voices in Latin America since the last wave of military regimes receded in the 1980s. By comparison with the long roll call of Central American despots over the centuries, Ortega is far from being the most barbaric. But by the values and standards of 21st-century political life in the region, he stands out as a historical throwback, a mirror to the dictator he helped overthrow 42 years ago, and an aberration.

The deeper problem for Latin America, and for the United States, is that Ortega may not be so aberrant after all. Cuba is still a one-party state. Meanwhile, other governments across Central America and further south have been probing and, in some cases, trespassing the outer limits of acceptable democratic behavior, tugging at the seams of their constitutions and meddling with their judiciaries. President Nayib Bukele seems to be using his astonishing popularity to lay the groundwork for long-term personal rule in El Salvador; Venezuela’s government has ended up largely victorious in a battle with the opposition by intimidating critics, manipulating elections, and seizing control of state institutions; and Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro has turned time and again to the military to staff and support his hard right government. Opinion polls from across Latin America report a growing public embrace of strong rule by the executive branch.

Ortega’s draconian turn is possibly the most extreme case of a president who sees no chink of light between his personal interests, political vendettas, and the nation’s well-being. Seemingly driven by the fear of losing power alongside a cold calculation as to the perceived low costs of persecuting his rivals, his moves represent an acute dilemma for Western partners. Ideally, foreign governments would find a way to deter him from quashing opponents without in the process causing diplomatic tensions to escalate wildly and humanitarian crises or migration flows to worsen. The region at large will be watching closely to see what, if anything, can soften the patriarch’s grip.

‘A Rare Display of Unity’

For the moment, Ortega’s penchant for locking up his rivals stands well beyond the bounds of the acceptable, and Latin America has let him know it.

Since Nicaragua’s spurious polls on Nov. 7, the region has responded with a rare display of unity, even if concrete punitive measures still lag behind. A clear majority of member-states attending the General Assembly of the Organization of American States (OAS) repudiated the polls, with Nicaragua alone in opposing a motion that deemed the elections not to be free or fair. Further action against Nicaragua under the terms of the Inter-American Democratic Charter is now on the cards, and could potentially trigger the country’s suspension from the OAS. Sensing the danger expulsion might pose, Ortega has already started proceedings to withdraw from the body before it could suspend him (the entire separation process takes up to two years), arguing that the multilateral body has been used as a tool of U.S. imperialism. He also agreed with Argentina and Mexico on the return of their ambassadors, who had been withdrawn from Managua after their governments’ mild criticism of Ortega’s chokehold over the elections was met with a ferocious rebuke from Nicaraguan officials.

Whether the Democratic Charter is invoked or not, many Latin American states rightly fear the effects of totally isolating Managua, which could shut down all communication channels and make Ortega less willing to observe Inter-American human rights obligations. Their preference is to stay diplomatically engaged. In its latest assessment on Nicaragua, the Permanent Council, the other political arm of the OAS, mandated the body’s secretary general and a diplomatic delegation to approach Ortega with the aim of persuading him to make concessions, such as freeing political prisoners and resuming talks with the opposition. But expectations are low: a similar delegation was refused entry to the country in 2019.

Repudiation of the Nicaraguan government has also surfaced further afield. At least 45 countries have criticised Ortega’s re-election and taken action at the bilateral and multilateral level. The United States has led the chorus of disapproval, imposing new rounds of targeted sanctions, including an entry ban on virtually all Ortega allies in government, security forces, judiciary, and anyone who “act[s] at their behest”, and the signing of the Reinforcing Nicaragua’s Adherence to Conditions for Electoral Reform Act that Congress had previously approved, which promises further tough diplomatic and possibly economic measures, including a review of Nicaragua’s free trade agreement with the United States. Britain and Canada also extended their lists of sanctioned individuals. The European Union, while declaring that the polls had converted the country into an autocracy, has not yet taken further action.

How Far Will Ortega Go?

The effects on events in Managua of this uneven pile-up of pressure, partial ostracism, and exhortation remain uncertain. For now, two main issues are set to determine the next lurch in the Nicaraguan crisis. The first is a primarily a matter of national politics and public sentiment. In short, how far will Ortega’s repressive gambit go, and what risks will it entail for him? The president appears to have calculated the costs of his wave of repression to be low, and the loyalty of his officials and compliance of his citizens to be high. Entry into Nicaragua is being systematically denied to journalists and researchers (the last visit by Crisis Group came before May), making it hard to say whether the president’s assessment is accurate or as wayward as his misreading of the public temperature in 2018, when he was completely unprepared for the mass protests that broke out against him and his wife Rosario Murillo, who serves as vice president.

Ortega’s readiness to deploy ever greater state violence to defend himself from a major uprising can be assumed after his crackdown against those protests, in which police and para-police forces caused over 320 deaths, many of them students. Yet even if the government lifted its de facto police-led state of siege, a wave of public unrest may not be the immediate outcome given the opposition’s disarray. The government could in theory use a modest political opening to regain some legitimacy at home and abroad. Then again, Ortega seems ill-disposed to find out just how deep and wide public grievances may have become.

Punishment and its Limits

A second set of questions goes to the heart of the U.S. and Latin American quandary in handling autocrats convinced of the supreme value of their prolonged rule. If tougher measures of the sort being contemplated by the United States are likely to generate greater poverty and isolation for Nicaragua, would they not risk fueling instability that foreign powers may come to regret? And would they not be repeating the faulty premises used against President Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela, when breezy assurances in early 2019 that chavismo had only hours left in power, despite its two decades in government, were minted by top U.S. and Latin American officials out of thin air and flimsy intelligence? In fact, turning Nicaragua into a pariah state would appear counterproductive if it is not accompanied by some strategy for either swaying Ortega into changing his approach, or persuading his colleagues to ease him out of power.

None of that is likely to be easy. Within Nicaragua, it is often said that Ortega is unlikely to step down because of the trauma of losing office in a landmark poll at the end of the country’s civil war. “Handing over power in 1990 was his life’s greatest mistake, and he’s determined to not make it ever again,” warned an opposition representative in a private conversation. Moreover, as the journalist Fabián Medina Sánchez shows in his unofficial biography of the president, Ortega appears profoundly attached to the business of fighting for his life. Asked in an interview in the 1980s about what it was like to leave Cuba, where he had taken refuge after being released from a seven-year stint in Somoza’s jails, to rejoin the guerrillas fighting against the dictator, he replied as follows:“We had to find places to hide in. There were battles and some comrades were killed. But I felt comfortable, I felt good. I felt a lot better than when I had been completely free.”

Dialogue and Crackdown; Fear and Opportunity

Ortega’s approach to opponents has not always been to incarcerate them. In fact, his strategy to handle the eruption of unrest three years ago and its aftermath has been sensitive to volatile political circumstances and the ties binding the coalition that sustains him.

Before 2018, Ortega had already tilted the electoral playing field in his favor and progressively extended his grip over state institutions. But he had sweetened this concentration of power by attempting to appease longtime foes, including the private sector, the United States, and the Catholic Church (by, for example, backing one of the strictest laws on abortion on the continent). The United States had tended to content itself with the country’s robust economic growth, low levels of violence, and almost non-existent northbound migration, as well as fluid cooperation on counter-narcotics. But these relations — particularly with the church, which is perceived to have sided with the anti-Ortega protestors — are now compromised.

The surge of mass protests and international outcry at the subsequent government crackdown spurred Ortega toward dialogue, but always with the aim of easing pressure rather than making fundamental concessions. He offered talks with the opposition at the height of street protests in 2018, when roadblocks had paralyzed much of the country, and early in 2019, when U.S. sanctions were still a novelty and seemed primed not only to topple him, but also one of his key international allies and financial patrons, Venezuela’s Maduro. Despite pressing him into certain compromises, such as allowing entry to international human rights bodies in 2018 and releasing almost 500 political prisoners in 2019, these efforts proved largely unsuccessful.

So, what explains the move to intensified repression ahead of the Nov. 7 polls? The relentless hounding of all opposition derives from two main sources: the fear of giving up power, and the opportunity provided by an absence of domestic and international pressure to halt him. Giving up power is a “life or death issue” for Ortega, in the words of one Managua-based diplomat, due to the risks of judicial charges over the human rights abuses in 2018 and the improbability of another political comeback. At the same time, his foes have been easy to cow. After the second round of talks broke down in mid-2019, opposition movements settled back into a series of internal spats that fueled public disenchantment with these forces. Meanwhile, the Sandinista support base seems barely to have been dented by the mass protests three years ago or the economic downturn that followed. Neither the government’s initially carefree approach to the COVID-19 pandemic nor the secretive burials of alleged victims of the virus appears to have affected the ruling couple’s fortunes, whose support has remained stable at around 25 to 30 percent.

Ortega has also gauged the international effects of his actions. After the unrest in 2018, foreign governments approved multiple resolutions on Nicaragua, slapped sanctions on officials, and, in the case of the OAS, even joined the second round of talks as guarantors. But the pandemic ended most of these diplomatic forays. Nicaragua disappeared almost entirely from the international spotlight as donors and regional neighbors focused exclusively on stemming the pandemic and containing its domestic fall-out. At the same time, Latin America’s regional bodies have been facing their own political and reputational crises, with the OAS undermined by its controversial role in the 2019 elections in Bolivia and support for the failed efforts to overthrow Maduro.

Fear and opportunity have defined Ortega’s repressive calculus. But in certain ways they also fall short of explaining the severity of the crackdown, and the obsessive targeting of individuals who once stood alongside Ortega in the guerrilla campaign and the revolutionary government. Ex-guerrilla comandante Dora María Téllez and former vice president Sergio Ramírez, also one of Nicaragua’s most prominent novelists, stand out as the sort of “restless” intellectuals and turncoats whom Ortega seems to believe deserve exemplary punishment (Téllez is in jail, Ramírez in exile).

An absolute inability to share territory with dissenting comrades or overlook their perceived treachery smacks more of pathological animus than strategic calculation. Yet even when operating out of personal loathing Ortega still seems aware of the effects that a collection of high-level political convicts may have on the government’s access to resources and domestic support. This may be the reason why he suggested sending detained opponents to the United States the day after the election, arguing they had “ceased to be Nicaraguans,” or why some of his deputies have relaunched the idea of staging a national dialogue next year, though one that would no doubt be tailor-made for Ortega by excluding the most critical voices and those he regards as disloyal. Walmaro Gutiérrez, an Ortega loyalist in Congress, laid it out clearly: “We will open a great national dialogue … in that dialogue will fit those who love Nicaragua, not those who demand sanctions.”

The Undesired Effects of Pressure

Faced with a recalcitrant and irascible government, the United States and others appear ready to ratchet up sanctions on Nicaragua in the hope that these could chip away at Ortega’s support base. Part of the plan appears to be to adopt a more targeted approach than in Venezuela, with the intention of singling out Ortega’s family, government allies, and the military so as to sap the leadership’s determination to resist concessions.

Even so, a radical intensification of sanctions and deepening of Nicaragua’s isolation brings with it the threat of blowback. The risk that is probably most palpable to Washington is migration. Political oppression and worsening living conditions in Nicaragua after three consecutive years of economic contraction have prompted a fresh wave of emigration, but this time with repercussions at the U.S. border. Almost 72,000 Nicaraguans were apprehended at the U.S. frontier with Mexico between January and November 2021, up from around 2,000 in the same period last year. This total has never been seen before for a country that traditionally exported its poor and persecuted to next-door Costa Rica. It is even possible that Ortega might come to see emigration flows as a useful element in influencing U.S. policy, preying on what is becoming Washington’s weakest flank in the region — its susceptibility to the inflammation of domestic right-wing populism by Central American leaders perfectly able to use their poorest citizens as levers of influence. Some have interpreted the recent move to lift visa requirements for Cubans as a way to turn Nicaragua into a bridge for those looking to flee the Castro government and reach the United States.

Well-established concerns as to the real rather than the intended or desired political effects of sanctions also apply in Nicaragua. Ortega has been upset by previous efforts to target his family, while sanctions have done little to produce cracks among his allies. Instead, in many cases they have caused the sanctioned to edge closer to the president as they come to see their fates as intertwined (as occurred to many high-ranking officials in Venezuela). In addition, the government seems to have fine-tuned ways to bypass sanctions, either by nationalizing companies that have been targeted or finding other frontmen to replace sanctioned officials in public institutions.

Broader economic sanctions offer an even bigger stick, and could become attractive to policymakers as a result. But they in turn would risk impoverishing an already poor nation, and could enhance public dependence on state handouts, as well as the state’s dependence on extra-regional allies like China and Russia. Ortega’s recent move to cut longstanding ties with Taiwan and re-establish formal relations with Beijing (he had already done so in 1985, before Violeta Barrios’ government reversed the decision in the 1990s) seems to hint at a search for powerful friends to counter Western censure. Harming the economy would also, obviously, fuel further migration outflows.

A third concern over sanctions turns not on their practical effects but on their intended goals. The OAS seems determined to call for fresh elections, but that appears an unrealistic objective under current circumstances. Ortega has shown himself ready to turn Nicaragua into a pariah if necessary to cling on to power. Any attempt to seek outright regime change is likely to stir his wrath, and could provoke retribution against opponents and fresh anti-imperialist tirades to galvanize his supporters, who might well resist any attempt to oust their leader. Simply repeating an election while the country is torn by resentment, and remains under the current pro-Sandinista electoral authorities and repressive legislation, would be unlikely to provide any solutions to its socio-political crisis.

Don’t Try to Wait Him Out

A growing number of governments long for Ortega’s abrupt demise. But the best they can do with the policies and attention spans at their disposal is seek the means to sway him and achieve some meaningful concessions. For that to happen, pressure will have to be married with diplomatic engagement. Foreign powers such as the United States and the European Union, alongside the OAS, should agree on the goal of creating the conditions for a negotiated way out of the crisis, rather than a sudden shift in power. To tempt Ortega into resuming talks with opposition groups, they should find common ground with his remaining allies in the region and elsewhere, while exploring the possibility of using experienced mediators to facilitate negotiations, not unlike the Norwegian-backed efforts to resolve Venezuela’s political conflict. Though the Venezuelan talks are currently on ice, at least they have pointed towards concrete progress on humanitarian relief and opening up political space rather than alluring but unattainable ideals.

Foreign powers should agree on a set of demands — among them the release of recently jailed opponents — that would represent a roadmap for Ortega to restore working diplomatic relations. Ideally his government would re-enter a dialogue process aimed at reaching agreements with opposition forces on reducing political tensions and providing justice for the victims of political violence. Waiting for a shuffle or rupture in the Sandinista ruling clique might seem preferable to trying to wring concessions out of the presidential couple. Yet Ortega still has another two decades to reach his mother’s age. It would be a long time to wait for Nicaragua’s solitude and misery to end.

Ivan Briscoe is the program director for Latin America and the Caribbean at International Crisis Group.

Tiziano Breda is the Central America analyst at International Crisis Group.

Photo by the Spanish Ministry of the Presidency