The Taliban Can’t Take on the Islamic State Alone

The Islamic State in Afghanistan’s six-year fight against the Taliban is now entering a new phase following America’s withdrawal. The group’s Aug. 26 Kabul Airport bombing, as well as a recent series of attacks against the Afghan Taliban in Nangarhar province, suggest that this new phase will almost certainly be a bloody one. Worse, the Islamic State in Afghanistan now enjoys a number of new advantages that will be difficult for the Taliban to overcome.

The Kabul airport attack was designed to garner regional and international publicity, demonstrate the Islamic State in Afghanistan’s operational prowess by targeting American personnel, and undermine the Taliban’s legitimacy in the eyes of Afghans and the world. The United States responded with an erroneous airstrike on alleged terrorist operatives, which only served to facilitate the Islamic State in Afghanistan’s propaganda and the self-righteousness of its message. The Nangarhar attacks, on the other hand, are a resumption of the group’s direct clashes with the Afghan Taliban. Given the Taliban’s peace deal with the United States and transition into a legitimate political entity, the Islamic State in Afghanistan now has the opportunity to frame the Taliban not only as illegitimate due to its links with the Pakistani state but also as an incompetent collaborator of the West – incapable of providing security and governance for the Afghan people. The Islamic State in Afghanistan has also benefited from the recent escape of thousands of members from prison. It is well-positioned to exploit tensions between the Taliban, who subscribe to the Hanafi school of Islam, and Afghans who adhere to the Salafist ideology, also referred to as Wahabbism. Additionally, the group has focused on sustaining its network of urban attack cells in Afghanistan and operational alliances with other regional jihadist groups. In short, while the Islamic State in Afghanistan has been significantly weakened in previous years by the loss of territory, fighters, and leadership, it has many factors working in its favor as well.

Top U.S. intelligence officials recently testified that although the Islamic State in Afghanistan, like al-Qaeda, may be motivated to attack U.S. interests, the risk is limited in the short term given the group’s recent losses and degraded capacity. Statements by the Taliban’s political spokesman and some Western analysts also suggest that the Taliban is able to tackle the Islamic State in Afghanistan independently. But a look back at the group’s origins and evolution, as well as the successes and failures of its fight against the Taliban, strongly suggest this faith is misplaced. Instead of waiting for the Taliban to defeat the Islamic State in Afghanistan on its own, Washington should engage more proactively in an inclusive, regional strategy. This would involve bringing together countries like China, Russia, Pakistan, and even Iran which have stakes in Afghanistan’s sociopolitical stability and in preventing the Islamic State in Afghanistan’s growth. A primary objective around which these countries could converge would be stemming cross-border militant movement, recruitment, alliances, and funding sources.

Origins and Goals of the Islamic State in Afghanistan

The Islamic State in Afghanistan first made headlines in early 2015 when the group announced itself as ready soldiers of the caliphate in the so-called Khorasan region. Historically, “Khorasan” referred to parts of present-day eastern Iran, Afghanistan, and Central Asia, but the Islamic State’s conception of Khorasan also includes Pakistan and some of India. Although that larger region remains part of the Islamic State in Afghanistan’s strategic vision, the group initially focused its operations in Afghanistan and Pakistan, using the latter more as a logistical hub. Founding members from the Pakistani Taliban, the Afghan Taliban, al-Qaeda, the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan , and other jihadist groups coalesced around a heavyweight former Pakistani Taliban commander named Hafiz Saeed Khan. He was the group’s first governor (referred to as either vali or emir) and was appointed by then Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant leader Abu Bakr al Baghdadi to oversee the group’s expansion into the Afghanistan-Pakistan region.

Not long after its official founding, the Islamic State in Afghanistan consolidated territorial control (tamkin, a requirement for recognition as an Islamic State province) in a number of rural districts in northeast Afghanistan. Over time, breakaway commanders from the Taliban and other groups tried to establish similar fronts in other provinces across the country and occasionally they succeeded. For almost seven years now, the group has launched highly lethal attacks in major cities and their surroundings, targeting government personnel and institutions. In addition to attacking international aid workers and journalists, the Islamic State in Afghanistan has also leveraged a sectarian strategy of violence similar to its namesake in Iraq and Syria, targeting minority groups like Afghanistan’s Hazara and Sikh communities and Pakistan’s Sufi and Zikri communities. By 2018, the Islamic State in Afghanistan was one of the top four deadliest terrorist organizations in the world.

Over time though, U.S.-led coalition operations and Afghan Taliban mobilizations (sometimes displaying a degree of tacit cooperation) whittled away at the Islamic State in Afghanistan’s territory, leadership, and rank-and-file member base. The group suffered a series of visible setbacks throughout 2019. The Islamic State’s core leadership sent a delegation to replace the failing governor Mawlawi Zia ul Haq and reorganized the movement by creating separate provincial entities (wilayat) for Pakistan and India (likely to ease management and to avoid internal disputes). Then, at the end of the year, hundreds of fighters and their families surrendered to the Afghan government, totaling almost 1,500 people by the start of 2020. Many experts even began to declare that the organization had been defeated.

Despite these losses, the Islamic State in Afghanistan has managed to survive, reconsolidate, and — now — resurge. Its operational alliances with other experienced regional groups and its ability to poach members of other organizations continues to enhance its operational capacity. While the Islamic State in Afghanistan’s initial ranks were swelled by disgruntled former Pakistani Taliban fighters, the group has proved capable of recruiting well beyond this. Organizations like the sectarian Lashkar-e-Jhangvi al-Alami, for example, have not only contributed to the Islamic State in Afghanistan’s local know-how but have also facilitated recruitment from within Pakistan’s Balochistan province. Thousands of recruits have also come from the Afghan Taliban, as well as from hardened Salafists in Afghanistan’s northeast, young Afghans in urban areas, and fighters across the border in Pakistan’s tribal areas. In the past, the Islamic State in Afghanistan also received substantial financial and logistical support from the Islamic State core leadership in Iraq and Syria.

Last year, a new governor named Shahab al Muhajir was appointed to oversee the organization’s resurgence strategy. Al Muhajir is an alleged expert in urban warfare with experience both as a Haqqani network commander and as an al-Qaeda member. His goal has been to guide the organization out of this period of relative decline first by doubling down on sectarian attacks against vulnerable minorities and then by launching a revitalized war against the Afghan Taliban. Under new leadership, the Islamic State in Afghanistan has been featured in the Islamic State-Central’s propaganda as a high-performing affiliate, with particular emphasis on high-profile and sophisticated operations such as the 20-hour prison siege in Jalalabad in August 2020.

The Taliban: A Necessary Rival

The Islamic State in Afghanistan has always viewed the Afghan Taliban as its ideological enemy, smearing the Taliban’s political project in Afghanistan and some of its governing practices as heretical. In 2015, then-spokesman for the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, Abu Muhammad al Adnani, issued a damning statement decrying the Taliban that set the stage for the violence to follow. More recently, the Islamic State in Afghanistan has updated its propaganda to defame the Taliban as collaborators of the United States. For example, a Telegram post on Aug. 26, 2021 stated, “History will record that these mercenary Talibs have become America’s protectors, soldiers, protégés and spies! Is there anything more humiliating than this?!!” In an editorial published in al-Naba, the Islamic State’s official weekly newsletter, following the Kabul attack, the Islamic State appealed to supporters of the Taliban and al-Qaeda to repent and embrace the “true” jihadist group.

The continued rivalry between these two groups is firmly rooted in their incompatible agendas and goals, and serves to create space for the Islamic State in Afghanistan in an otherwise saturated militant landscape. The Taliban’s goals are limited in nature. They were primarily interested in expelling Western forces from Afghanistan and establishing a government in line with their view of sharia. The Islamic State in Afghanistan, on the other hand, not only seeks to acquire the same territory as the Taliban but actively recruits other groups’ militants, challenges al-Qaeda, instigates sectarian violence, and targets multiple state actors.

One major avenue through which the Taliban-Islamic State in Afghanistan rivalry has played out is defections. Since its inception, the Islamic State in Afghanistan has poached hundreds of commanders and rank-and-file members from the Taliban. We have tracked dozens of mid- to senior-level Taliban commanders who swapped white flags for black, well over 30 of whom were later reported killed, captured, or surrendered to U.S.-led Afghan forces. Some of these commanders enjoyed greater success than others. Qari Hekmat (Hekmatullah), a former Uzbek Taliban commander, joined his forces with the Islamic State in Afghanistan and came to lead the group’s northern territorial project in Jowzjan province for an extended period of time. However, other former Taliban commanders like Saad Emarati — whose fledgling efforts in Logar province were dismantled in a matter of weeks — were quickly killed, captured, or forced to flee. Some even re-joined the Taliban when offered amnesty. Given the benefits derived from poaching Afghan Taliban members in the past, the Islamic State in Afghanistan is likely to capitalize on any internal divisions and disagreements within its ranks to find new recruits.

The Military Dimension

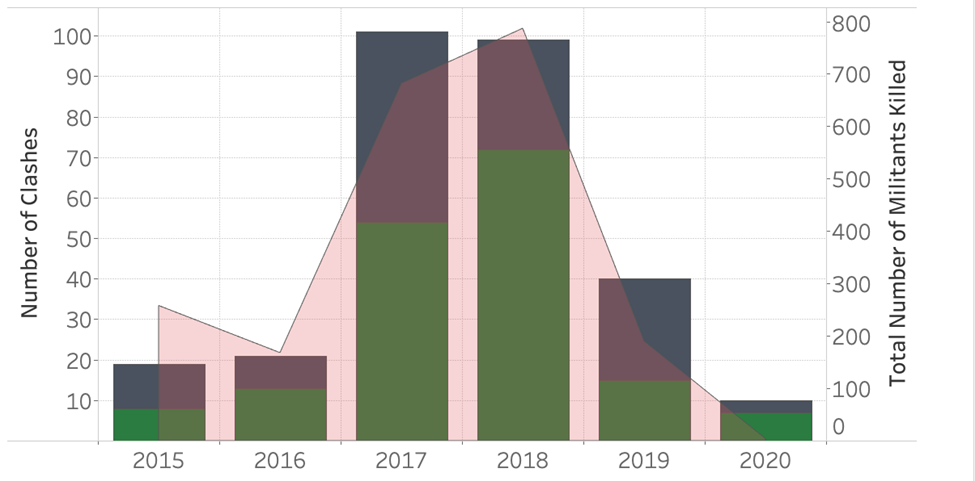

Of course, the Islamic State in Afghanistan’s rivalry with the Taliban has also taken more violent form. Figure 1 shows the number of clashes and fatalities incurred between the two groups between 2015 and 2020. Overall, the data show a dramatic escalation in clashes (armed engagements with at least one reported casualty) from 2016 through 2018, then a sharp fall in 2019 continuing through 2020. Despite facing an onslaught from Taliban forces, as well as airstrikes and ground operations from U.S. and Afghan forces, the Islamic State in Afghanistan still managed to match the Taliban in strikes initiated during 2017. By 2019, however, a decline in both attacks and their lethality is noticeable. This may be the result of losses dealt to the group by U.S.- and Afghan-allied operations.

Figure 1: Islamic State in Afghanistan-Afghan Taliban Clashes and Fatalities Over Time

![]()

Sources: Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project, Uppsala Conflict Data Program

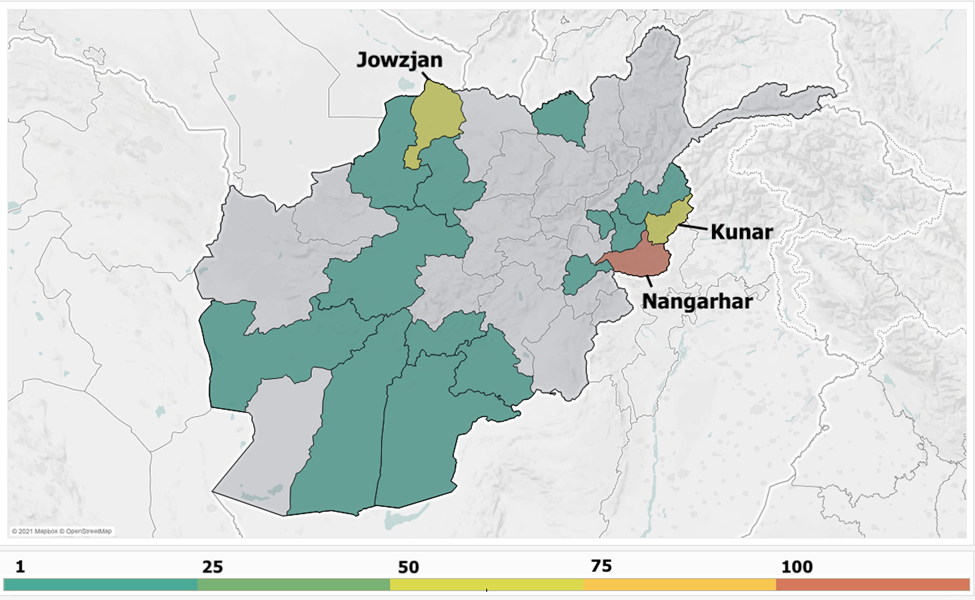

Figure 2 shows the distribution of clashes across Afghanistan’s provinces from 2015 to 2020. Geographically, the Islamic State in Afghanistan and the Taliban have clashed in at least 16 provinces, with the heaviest fighting falling in Nangarhar, Kunar, and Jowzjan. Notably, these are the provinces where the Islamic State in Afghanistan’s most significant consolidation and expansion efforts occurred and, as a result, where U.S. and Afghan coalition forces have most heavily targeted the group. This is not to say that major mobilizations of Taliban fighters and “special forces” units did not play a role in clamping down on the Islamic State in Afghanistan in these areas, but, in general, these efforts tended to coincide with state-led operations against it. For example, the Taliban routed the Islamic State in Afghanistan in early 2015 in Helmand, Zabul, and elsewhere, but these efforts piggy-backed on tactical U.S. strikes that eliminated its senior leadership.

Overall, it is clear that the Taliban has demonstrated some efficacy in limiting the Islamic State in Afghanistan’s expansion efforts, but the nature of these engagements also shows that the Taliban have benefited from coalition air power and direct action raids. While it is possible that any future territorial control by the group could be dismantled by the Taliban, historical trends suggest that this would come at a high cost in terms of casualties, possibly causing prolonged battles in the absences of coalition strikes and ground operations.

But preventing the Islamic State in Afghanistan from holding territory is just one of the challenges the Taliban faces. For now, at least, the Islamic State in Afghanistan’s strategy no longer appears to prioritize the costly struggle for territorial control. Instead, it is focused on leveraging operational assets to attack the Taliban, thereby signaling its resolve and boosting recruitment and outreach.

The question now is whether the Taliban will be able to engage in protracted counter-terrorism efforts while governing the country. The Islamic State in Afghanistan has embraced the same method of insurgency as its namesake in Iraq and Syria, one geared towards anti-state competition. This includes methodically infiltrating governing institutions, recruiting and politicking behind the scenes to form alliances, assassinating moderate voices of opposition within targeted recruitment populations, and launching attacks against both minority communities and state targets. With the Taliban now in power, it is Taliban personnel and institutions that, alongside civilians, will bear the brunt of the Islamic State in Afghanistan’s strategy.

Figure 2: Number of Islamic State in Afghanistan-Afghan Taliban Clashes by Province

Sources: Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project, Uppsala Conflict Data Program

What’s Next?

While the Taliban will no longer face the resource drain of waging an insurgency themselves, they do face the burden of transitioning into a state actor, constraining opposition to their rule, and extending governance across the country at a time of tremendous economic and humanitarian strain. The Taliban are heavily burdened with running the country and lack resources to ensure security for the Afghan population. Any effort to tackle the Islamic State in Afghanistan by the Taliban themselves will be prolonged and deadly, likely generating instability at both the national and regional levels.

On the other hand, with the U.S., NATO, and Afghan security forces now out of the picture, the Islamic State in Afghanistan can focus the vast majority of its operational resources squarely on the Taliban — especially its highly lethal attack operations — instead of splitting those resources to resist multiple actors. With experts widely assessing that the over-the-horizon capabilities of the United States are limited, the environment may rapidly become more advantageous for the Islamic State in Afghanistan to reinvigorate its terror campaign in the days ahead.

How might this play out? First, it is evident from the group’s recent propaganda campaign that the Islamic State in Afghanistan is highly likely to continue encouraging defections, particularly from the Taliban. If the Taliban, once in government, offers concessions or leniency on ideological matters, they risk losing fighters to their rival. If the Taliban are increasingly perceived to be pawns of outside powers, especially through counterterrorism cooperation with the United States or others, they again risk losing fighters to defection campaigns. Any level of counterterrorism cooperation with the United States is likely to trigger internal disputes within the Taliban, which could further increase the appeal of the Islamic State in Afghanistan among dissenting members. Defectors from the Afghan Taliban in particular can provide significant intelligence, which would facilitate more sophisticated attacks.

The potential resurgence of a resilient Islamic State in Afghanistan raises security concerns not just for the United States but for many regional state actors including Iran, Pakistan, China and Russia. Even if the United States engages in some counter-terrorism operations, without a sustained regional approach any gains are likely to be short-lived. For now, countries like China, Russia, Pakistan, and even Iran, which hold major stakes in Afghanistan’s future and hope to pursue their geo-economic interests there, may be best placed to jointly tackle the problem posed by the Islamic State in Afghanistan.

Although bringing these countries together around a security strategy would certainly be challenging, they could potentially find common ground in targeting cross-border militant movement, recruitment, and funding. Groups like the Islamic State in Afghanistan depend on foreign fighters for example. Regional coordination and intelligence sharing could allow governments to better track the movement of foreign fighters between conflict zones. Cooperation could also focus on tracking and disrupting cross-border alliances, which are a key source of the Islamic State in Afghanistan’s attack capabilities. They could also collaborate in identifying important nodes in the transnational smuggling of opium, timber, and minerals. Pakistan, China, Russia, and Iran have all put considerable stock in their future relationship with the Taliban. Washington can leverage this to make sure they all give the Taliban the support it needs to defeat the Islamic State in Afghanistan.

Amira Jadoon, Ph.D., is an assistant professor at the Combating Terrorism Center and the Department of Social Sciences at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. Follow her on twitter @AmiraJadoon. (The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not represent the official policy or position of the Combating Terrorism Center, U.S. Military Academy, Department of Defense, or U.S. Government).

Andrew Mines is a research fellow at The Program on Extremism at George Washington University. He tweets at @mines_andrew.

Image: Xinhua