The Royal Navy in the Indo-Pacific: Don’t Use a Sledgehammer to Crack a Nut

Why is the Royal Navy sending two of its smallest warships to the world’s largest ocean? The First Sea Lord’s announcement of the Royal Navy’s intention to forward deploy two offshore patrol vessels to the Indo-Pacific has been met with skepticism. Given the region’s sheer size and the growing menace of China within the South China Sea, some argue that a frigate is a better platform for this role. But using a frigate, the work horse of the fleet, for all overseas tasking is akin to using a sledgehammer to crack a nut. Each new maritime task needs to be judged on its own merits considering its objectives and operating environment.

While a small presence may signal weakness or vulnerability for a superpower navy such as that of the United States, Britain’s role on the international scene is different. As a middle power (albeit one with a blue-water navy) Britain’s strategy is more modest than that of the United States and, therefore, its approach should also be different. For a middle power, strategic messaging is the most important consideration. This article examines the Royal Navy’s options and considers tasking, threat assessment, and basing options, before it makes the case that, at this specific moment in time, a frigate is not an appropriate option for the Indo-Pacific.

Tasking

The integrated defense review identified NATO as Britain’s main defense effort and Russia as its main adversary. As a consequence, the bulk of the United Kingdom’s military remains focused on Europe and the Atlantic. Whilst deterrence is a primary task for any warship, the Integrated Review does not refer to deterrence in the Indo-Pacific. While recognizing North Korea’s destabilizing impact, it does not identify any adversaries in this region. At most, it describes China as an “increased risk to British interests,” but only as a “systemic competitor” that Britain should “engage with” and “remain open to.”

Britain’s “tilt” toward the Indo-Pacific signals growing recognition of the important role this region is likely to play in the coming decades. The United Kingdom’s application for membership of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership is an economic example. From a security perspective, the Integrated Review is much vaguer, although it does recognize the rise in major power competition that is developing in the South China Sea. The dilemma confronting the British government, therefore, is which takes precedence: security or prosperity? The maiden deployment of the Queen Elizabeth carrier strike group to the region is a golden opportunity for Britain to prioritize both security and prosperity, but a decision then needs to be taken for follow-on sustained presence operations, which would best be delivered through a British strategic document on the Indo-Pacific. A prosperity focus requires greater emphasis on presence throughout the region, capacity building with partners, and a less aggressive footprint. A security focus requires a more aggressively armed persistent presence that can operate alongside coalition partners and has a greater ability to defend itself. In the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, the departure from the European Union, and the need for the British military to support NATO, the British government’s focus in the Indo-Pacific ought to be on prosperity, since this is what supports its economy and wins votes at home. The recent decision to deploy two offshore patrol vessels to the Indo-Pacific over a frigate supports this view.

Threat Assessment

The Chinese People’s Liberation Army (Navy) poses the greatest military challenge to a British warship operating in the Indo-Pacific. Having recently become the world’s largest navy, and equipped with an anti-access/area denial capability that covers the majority of the central area of the Indo-Pacific, the Chinese navy is very much in a position of regional strength. China is not on a war footing, but major power competition is growing. This does not mean British ships should not operate there. On the contrary, by exercising their freedoms, the Royal Navy strengthens and upholds the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea and reinforces the international rules-based system. Should China wish to act against any type of coalition vessel in the South China Sea, it would do so in the full knowledge that there would be international repercussions. It would also mean that the United Kingdom’s strategic messaging of prosperity over security has failed.

Much as in the Cold War, nuclear deterrence is likely to keep some form of peace between the United States and China but, with the continued expansion of the Chinese navy, the likelihood of localized friction will increase with time and there may come a point where the British government will have to revisit its priorities. Putting aside the risk China poses, other risks originate from terrorist and pirate organizations.

Platform Options

The Royal Navy has a working fleet of six Type 45 destroyers, 13 Type 23 frigates and eight offshore patrol vessels, as well as three civilian-manned Bay class Royal Fleet Auxiliary support ships that rotate through 14 standing commitments. In addition to these, it has 13 mine countermeasure vessels, four survey vessels, and a number of fleet support vessels which will not be considered here since they are needed elsewhere. The ability for a submarine to deter is not in dispute, but their ability to perform surface ship tasks, such as boardings, disaster relief, or constabulary operations is limited. The main components of the Royal Navy’s carrier strike group and littoral response groups have also not been included here as they will be used in a surge capacity providing deterrence and enhanced presence where required. The Type 45 destroyers will provide the ring of steel around these task groups and will have therefore been removed from consideration due to their limited numbers. The delivery of the Type 31 multi-purpose frigate circa 2026, and the announcement of the Type 32s, will be seen as likely long-term solutions to the already forward deployed offshore patrol vessels but may also be used to supplement them for increased presence across the region. Potential naval solutions for a persistent presence in the Indo-Pacific can therefore be narrowed down to just three options: a Type 23 frigate, the civilian-manned Bay class support ship, or the offshore patrol vessels.

The Case for the Frigate

The Type 23 frigate represents the cutting edge of the United Kingdom’s maritime anti-submarine warfare capability and is able to deliver across all areas of defense diplomacy. However there are only 13 of them, and they cannot be used for every task. The fleet commander, Vice Adm. Jerry Kyd, said he would love a fleet of 50 frigates, but that is a historically binary posture (you deploy a frigate or you deploy nothing), and the Royal Navy needs to become more agile and flexible. This requires employing the right ship for the task to conserve resources and not defaulting to the frigate for every task. A frigate’s crew size of around 200 is manpower-intensive, and the need to conduct crew rotations without base port infrastructure, such as accommodation during crew swaps, would make it an expensive option for forward presence. The advantage of such a large crew is that it has the manpower to conduct disaster relief operations, and the ship’s size also means they can carry adequate stores for emergency use, as well as an embarked helicopter to assist in the delivery. Of the three options, frigates have the deepest draft (7 meters), which reduces the number of ports they can enter to perform defense diplomacy. A frigate undoubtedly meets all the requirements for a security-focused strategic message. Of the three options, a frigate would provide the best option to conduct deterrence, and it would bring warfighting capabilities that will aid coalition operations. The dilemma in deploying a frigate is that it prioritizes security over prosperity and is more provocative than deploying a less-aggressively armed ship at a time when Britain is trying to develop an economic partnership with China. Unlike Britain’s naval presence in the Persian Gulf, the current risk assessment within the Indo-Pacific region does not require such high-end capabilities to be permanently stationed there. If this situation were to change in the future, the Type 31 frigates will be available from 2026.

Figure 1: Type 23 Frigate

Source: U.S. Navy (Photo by Mass Communication Spc. 1st Class Peter Burghart)

The Case for the Bay Class Royal Fleet Auxiliary

Supply ships have been undertaking lower-risk forward deployments across the globe for many years, and this necessitates their inclusion in the debate. RFA Cardigan Bay has been forward deployed in the Middle East since 2017 supporting British minehunters stationed there. RFA Mounts Bay spent three years in the Caribbean providing hurricane relief. These types of ships are, therefore, very well-suited to providing forward presence globally. Fitted with a complete aviation suite (including the option for a temporary hangar), a crew of 70 with accommodation for up to 700 additional personnel, and an abundance of storage space, they are possibly the best options for delivering humanitarian aid and disaster relief. This type of ship’s ability to deploy an amphibious capability may be seen as too provocative in its strategic messaging, as one never knows what they may be carrying. And, with the concept of the future commando force looking to deliver two littoral readiness groups, the Bay class support ships are likely be in high demand.

Figure 2: Bay Class Royal Fleet Auxiliary

Source: U.S. Navy (Photo by Mass Communication Spc. 1st Class Michael Sandberg)

The Case for the Offshore Patrol Vessel

The last option for forward deployment comes from the Royal Navy’s eight offshore patrol vessels. The three older ships undertake maritime security and fishery protection around the United Kingdom and, due to their age, are unlikely to be worth investing in heavily for tasking further afield. The five new ships are the greenest platforms in the fleet and have received design enhancements such as an extended range, faster top speed, additional accommodation for Royal Marines, an upgrade from a 20 millimeter to a 30 millimeter gun, the addition of two mini-guns for self-defense, and the ability to operate drones. With a crew of just 58, they are the most economical solution of the three choices, and, with a draft of just 3.8 meters, they can use smaller, lower-priced berths in a greater number of ports, as well as the military ports of allies that may have a coastal or brown-water navy and whose facilities may therefore be well-suited to accommodate ships up to the size of the offshore patrol vessel. Unfortunately, they are not equipped with a hangar, so a helicopter cannot be permanently embarked, but the flight deck is capable of receiving and refueling helicopters up to the size of a Merlin. Although not delivering the same clout and deterrence that a frigate could, the arrival of two offshore patrol vessels in the Indo-Pacific will provide some benefits over a frigate. The Royal Navy can build valuable situational awareness more quickly by having two ships dispersed across the vast region than would be provided by a single frigate, and their less provocative armament suite may allow it greater autonomy to roam.

Military Basing

The United Kingdom has several allies and partners upon which it can rely for in-theater support, including through the Five Powers Defense Arrangements; historic connections through the Commonwealth; and military partnerships with Australia, France, Japan and the United States, all of which have their own military bases across the region. There is also the new British military logistics base in Duqm, Oman and the British Indian Ocean Territory in Diego Garcia. The idea of constructing more British overseas military bases is unlikely to appeal, either to regional powers, where the days of empire have yet to be expunged from memory, or back home, where the voting population’s focus is on support to the National Health Service and economic recovery in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. Brunei has been identified as a possible support hub, but its military harbor is currently incapable of accommodating the larger draught vessels, such as frigates or Bay class auxiliaries. Singapore already plays host to a small logistics support facility but, due to its hedging relationship with China, is unlikely to want to host more.

Three of the new offshore patrol vessels have already been forward deployed to the Mediterranean and South Atlantic, where they use established British military operating bases, and the Caribbean, where civilian and allied military ports are used for support. A concept of forward deployment similar to the Caribbean is likely to be the most politically acceptable, economically affordable, and therefore most appealing for use in the Indo-Pacific, given the number and dispersed nature of Britain’s partners there. This will give the greatest flexibility for a persistent maritime presence to patrol across the vast region without being tied to a single base port and without the associated problems that come with a static base in terms of force protection.

Conclusion

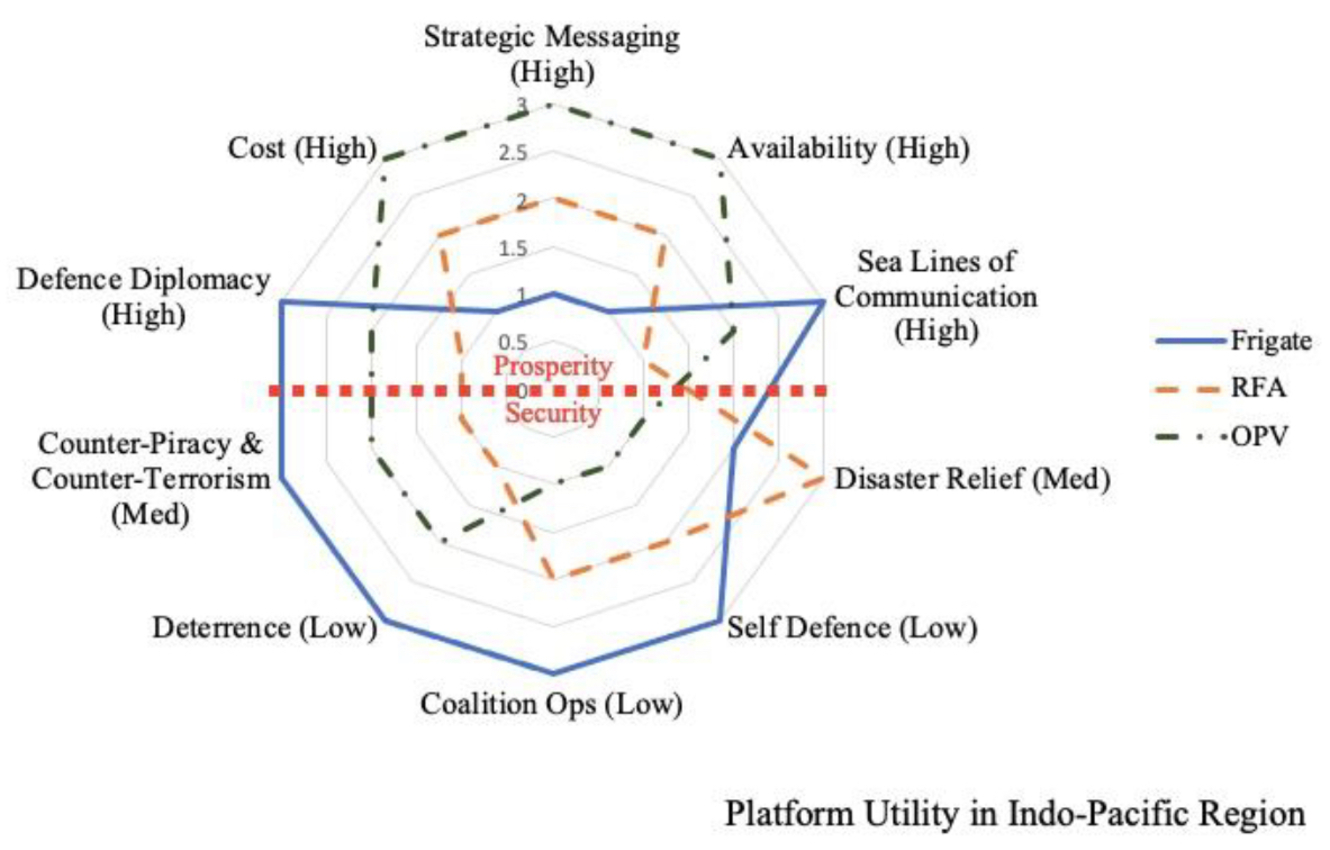

Drawn from personal experience, the diagram below depicts the essential tasking elements. The red dotted line delineates the prosperity versus security focus. It will come as no surprise that the frigate option is the most capable ship (largest area in the diagram), and this may explain their default status for overseas tasking. However, a frigate’s strategic messaging prioritizes security over prosperity, with the majority of the area falling below the red dotted line. The offshore patrol vessel comes in second due to its ability to deliver on routine tasking, its availability, cost, and the more aligned strategic messaging this ship delivers. The Royal Fleet Auxiliary’s amphibious capability, whilst very capable in the delivery of aid, favors security. Its availability is also questionable, and its status as a civilian support vessel may limit its effectiveness in delivering defense diplomacy.

Figure 3

Source: Generated by the author.

The British government’s strategic messaging is key in the decision process. If security and deterrence were the primary objectives, then a frigate would likely be the best option, with HMS Montrose (currently forward deployed to the Persian Gulf) being the most likely candidate. If prosperity is the primary objective, then two offshore patrol vessels can better deliver this than any single ship. Whilst not the most capable warfighting vessel in the Royal Navy’s inventory, the offshore patrol vessel is economically viable, which will be important to the British public, who might not yet understand the strategic importance of the region and the need to start getting involved. The decision to deploy two platforms sends a clear message that Britain is committing to the region and the visit of the Queen Elizabeth strike group is a timely reminder of what else is available, should deterrence be required. The offshore patrol vessels provide a readily available persistent maritime presence today, with room to expand once more ships enter service. It all comes down to the strategic messaging Britain wishes to deliver. With the desire to achieve an economic relationship with China, smaller vessels deliver an aligned strategic message, leaving the sledgehammer for when it is truly required.

Cmdr. René Balletta is a serving Royal Navy warfare officer of 29 years who is currently assigned as the Hudson Fellow to St Antony’s College, Oxford and is a visiting fellow of the Changing Character of War Centre at Pembroke College, Oxford. A defense engagement specialist, he is a graduate of the French War College, École de Guerre, and has a master’s in international relations from the Sorbonne.

All views are the author’s own and not the views of the British government, Ministry of Defence, or the Royal Navy.

Image: U.S. Navy (Photo by Mass Communication Spc. 2nd Class Claire DuBois)